Crew 44 – Assigned 754th Squadron – October 1943

Shot down April 25, 1944 – MACR 4342

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Crew Position | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

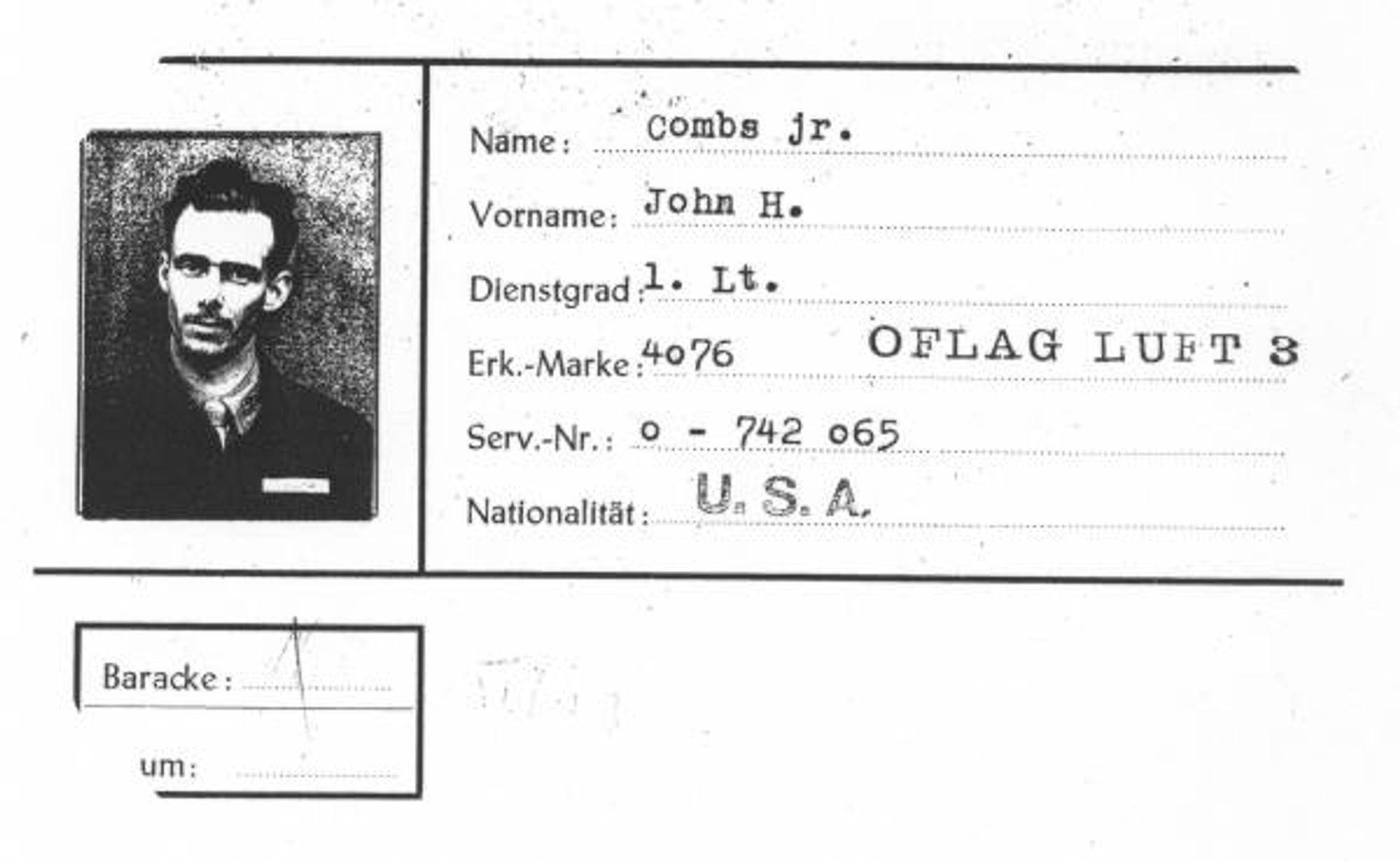

| 1Lt | John H Combs | 0742065 | Pilot | 25-Apr-44 | POW | Stalag Luft III |

| 2Lt | Charles W Roof | 0810224 | Co-pilot | 25-Apr-44 | EVD | E&E Report 848 |

| 2Lt | Jacob E Maze | 0811655 | Navigator | 08-Mar-44 | UNK | Mission to Berlin |

| 2Lt | Charles G Bieber | 0688166 | Bombardier | 25-Apr-44 | KIA | Queens County, NY |

| T/Sgt | Robert O Behrens | 36435582 | Radio Operator | 25-Apr-44 | EVD | E&E Report 770 |

| T/Sgt | John B Waag | 39184240 | Flight Engineer | May-44 | CT | Purple Heart for wounds April 9 |

| S/Sgt | Harold L Holbrook | 15332499 | Gunner/2E | 05-Jul-44 | CT | Reld from 60SC |

| S/Sgt | Anthony B McKeon | 33580391 | Top Turret Gunner | 25-Apr-44 | EVD | E&E Report 771 |

| S/Sgt | Harry L Tamboer | 32557920 | Waist Gunner | 25-Apr-44 | KIA | Passaic County, NJ |

| S/Sgt | Richard O McCarthy | 32745523 | Tail Turret Gunner | 25-Apr-44 | KIA | Delaware County, NY |

Training with the 458th in Tonopah, Nevada in the fall of 1943, Crew 44 was a part of the 754th Squadron and flew over to England via the Southern Ferry Route in January 1944. Prior to Combs’ crew being sent overseas Sgt Samuel R. Hudson was replaced by S/Sgt Harry L. Tamboer.

Combs’ crew was designated as a lead crew early on and flew their first mission on March 2, 1944 to Frankfurt. They were in the group deputy lead slot with Lt. Col. Hogg as command pilot. On their next ten missions the crew flew two group leads, two squadron leads, and four deputy leads. On April 25th, the crew’s last mission, they flew in the group deputy lead slot, but did not carry a command pilot.

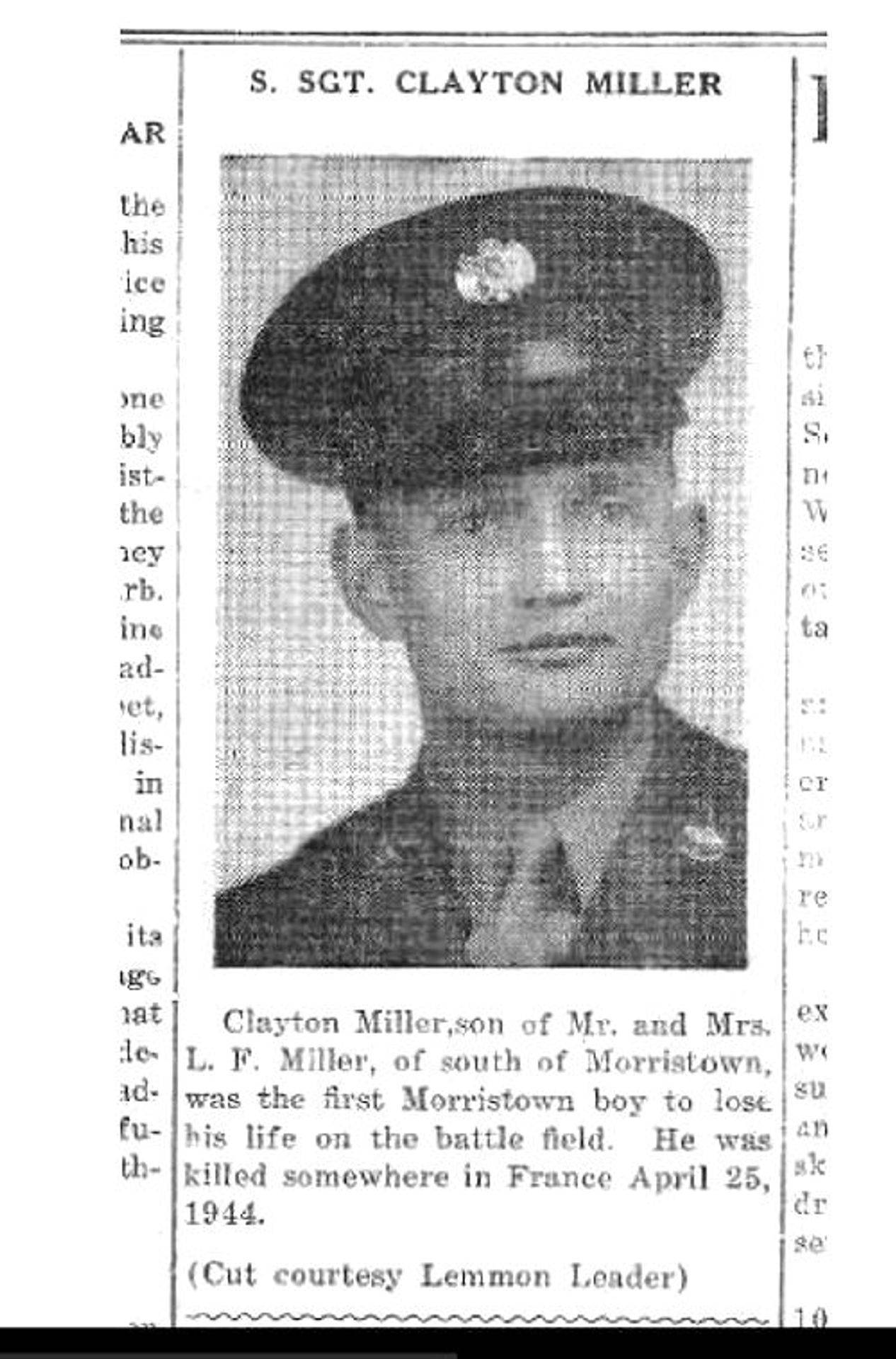

There were several crew substitutions on the April 25th mission to Mannheim, Germany. 2Lt. Eugene Hoag [Evaded – E&E Report 769] from Crew 40 had replaced 2Lt. Jacob Maze (who had been transferred to the 93BG on April 15, 1944) as Navigator, and S/Sgt Clayton L. Miller [Killed In Action] and T/Sgt Joe Wagner [POW – Stalag Luft 4] replaced Sgt’s Holbrook and Waag as gunner and engineer respectively. After Combs’ crew was lost, Holbrook took Wagner’s place on Crew 51 and completed his tour in June 1944. According to a family member of Sgt Waag, he was seriously wounded on the April 9th mission to Tutow when the 458th lost four aircraft and crews. While over Kiel Bay en route to the target, a bullet from an ME-109 hit the muzzle of Waag’s gun, deflecting fragments into him. He was hospitalized until late August when he resumed combat flying and completed his tour, flying several missions with Lt William W. Swartz as pilot. Mechanics removed the barrel of his damaged gun, mounted it, and presented it to him as a memento.

Combs took off that morning at 6:09 AM. According to the S-2 Mission report, after the group had crossed the French coast, “Approximately twenty enemy fighters variously described as ME-109’s and FW-190’s attacked the lead flight of the lead squadron at 0855 hours just east of Vitry, France. The attack was made from twelve to one o’clock high out of the sun after the E/A had simulated the actions of friendly fighters escorting the formation from sufficient distance to be recognizable. The tactics employed were in the nature of a scissors attack with half of the fighters swooping down through our formation while the remainder passed below. One of our A/C was shot down and two suffered major battle damage.”

Combs plane was hit hard in the tail section and according to co-pilot Charles Roof, “the plane was out of control caused by a fighter shooting off the tail; elevator damaged beyond usefulness.” Eugene Hoag, substituting for the crews regular navigator, recalled that, “elevator controls [were] damaged, [and] both fins shot off; no fire.”

Eight of the crew were able to bail out. For reasons unknown two men, Clayton Miller and Harry Tamboer did not exit the plane, and both of their bodies were found in the wreckage. In a questionnaire filled out by Eugene Hoag, he recalled that Miller was last seen in the plane near his station in the waist and that he was uninjured. Hoag also remembered that Tamboer had his parachute on in the waist when the plane was still at 20.000 feet.

Bombardier Charles Bieber did make it out, but delayed his jump until it was too late. His parachute did not have time to fully open and he was seen lying about forty feet from the plane near his partially deployed parachute. Tail gunner Richard McCarthy also made it out of the plane, but conversely to Bieber he opened his chute too soon. It fouled the wing and he was dragged down to the ground with the aircraft. All four of these men were buried, according to Hoag, “by Maurice Collet of Le Buisson, Par Haussignemont, Marne France. I was staying at his home at the time.”

John Combs was captured fairly quickly by a German corporal on a transport train. Joe Wagner made it to the Spanish border before being captured. Both men were eventually taken to prison camps in Germany.

With the help of the French Underground, four of the crew, Roof, Hoag, Behrens, and McKeon were able to successfully evade capture and in June all but Roof were back in England. Roof made it back at the end of July.

————————-

MACR 4342

Combs’ A/C was hit by ME-109’s east of Vitry, France at 0857. He pulled up, stalled out, fell off to the left and went into a flat spin. One rudder was seen to come off and three crews reported that A/C crashed on ground. Reports on number of “chutes” seen vary from one to seven with four “chutes” the consensus.

Missions

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Cmd Pilot | Ld | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 02-Mar-44 | FRANKFURT | 1 | 1 | HOGG | D1 | 42-100366 | B | Z5 | 1 | MIZPAH | |

| 05-Mar-44 | BORDEAUX/MERIGNAC | 3 | 2 | HOGG | L2 | 42-100357 | D | Z5 | 1 | VALE OREGAN | |

| 08-Mar-44 | BERLIN/ERKNER | 5 | 3 | FEILING | L1 | 42-100357 | D | Z5 | 2 | VALE OREGAN | |

| 18-Mar-44 | FRIEDRICHSHAFEN | 9 | 4 | O'NEILL | L1 | 42-100357 | D | Z5 | 3 | VALE OREGAN | |

| 22-Mar-44 | BERLIN | 11 | 5 | MOORE | D2 | 42-100357 | D | Z5 | 5 | VALE OREGAN | |

| 24-Mar-44 | ST. DIZIER | 13 | 6 | HINCKLEY | D1 | 42-100357 | D | Z5 | 6 | VALE OREGAN | |

| 26-Mar-44 | BONNIERES | 14 | ABT | 42-100357 | D | Z5 | -- | VALE OREGAN | ABORT - NAV SICK | ||

| 09-Apr-44 | TUTOW A/F | 18 | 7 | 42-100357 | D | Z5 | 8 | VALE OREGAN | |||

| 12-Apr-44 | OSCHERSLEBEN | REC | -- | OLLUM | D1 | 42-100362 | A | Z5 | -- | SWEET LORRAINE | RECALL |

| 18-Apr-44 | BRANDENBURG | 22 | 8 | HENSON | L | 42-100341 | A | J4 | 10 | SATAN'S MATE | LtCol HOGG also listed |

| 20-Apr-44 | SIRACOURT | 24 | 9 | HENSON | D1 | 42-100357 | D | Z5 | 9 | VALE OREGAN | JOHNSON (LEAD NAV) |

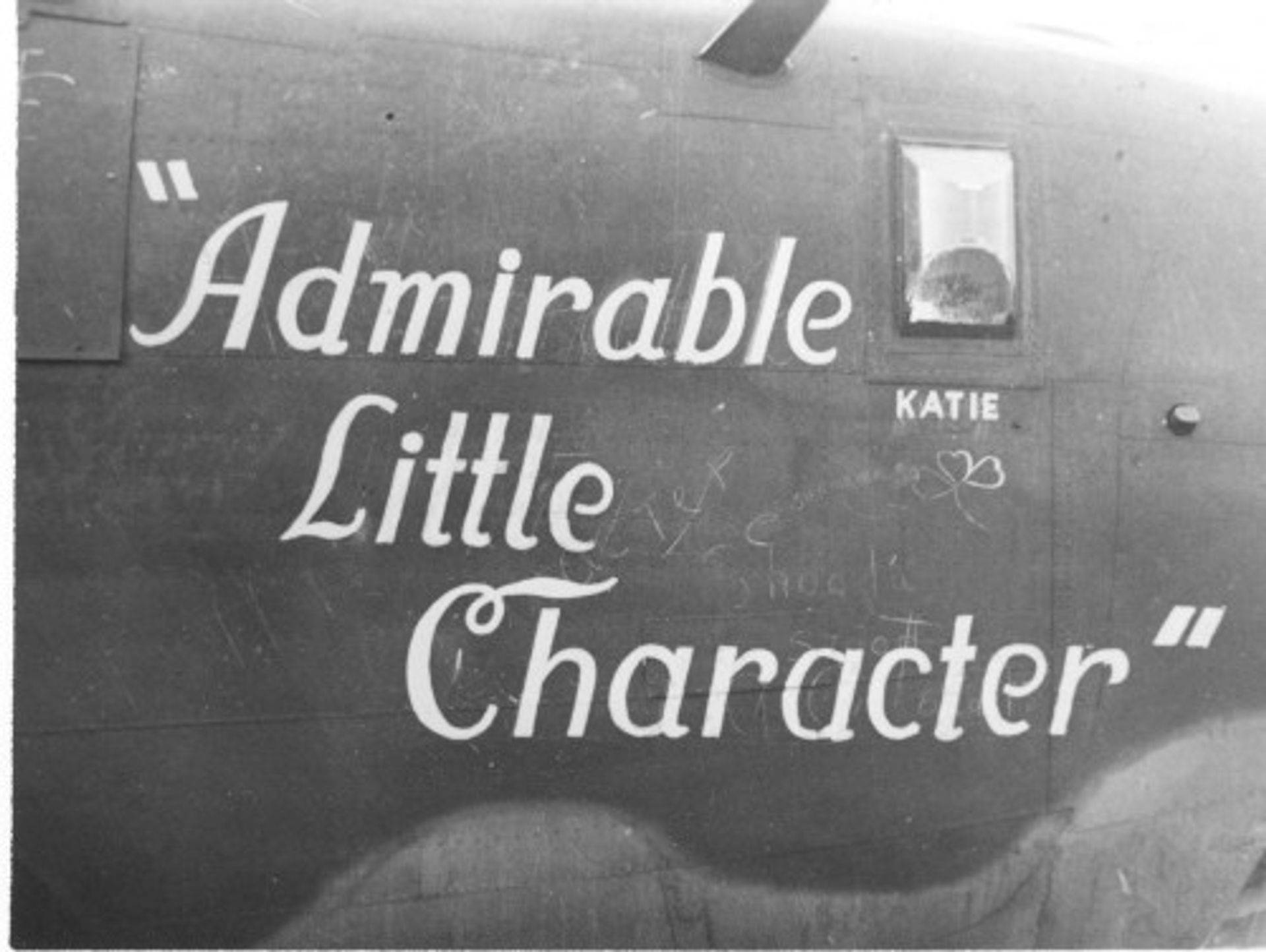

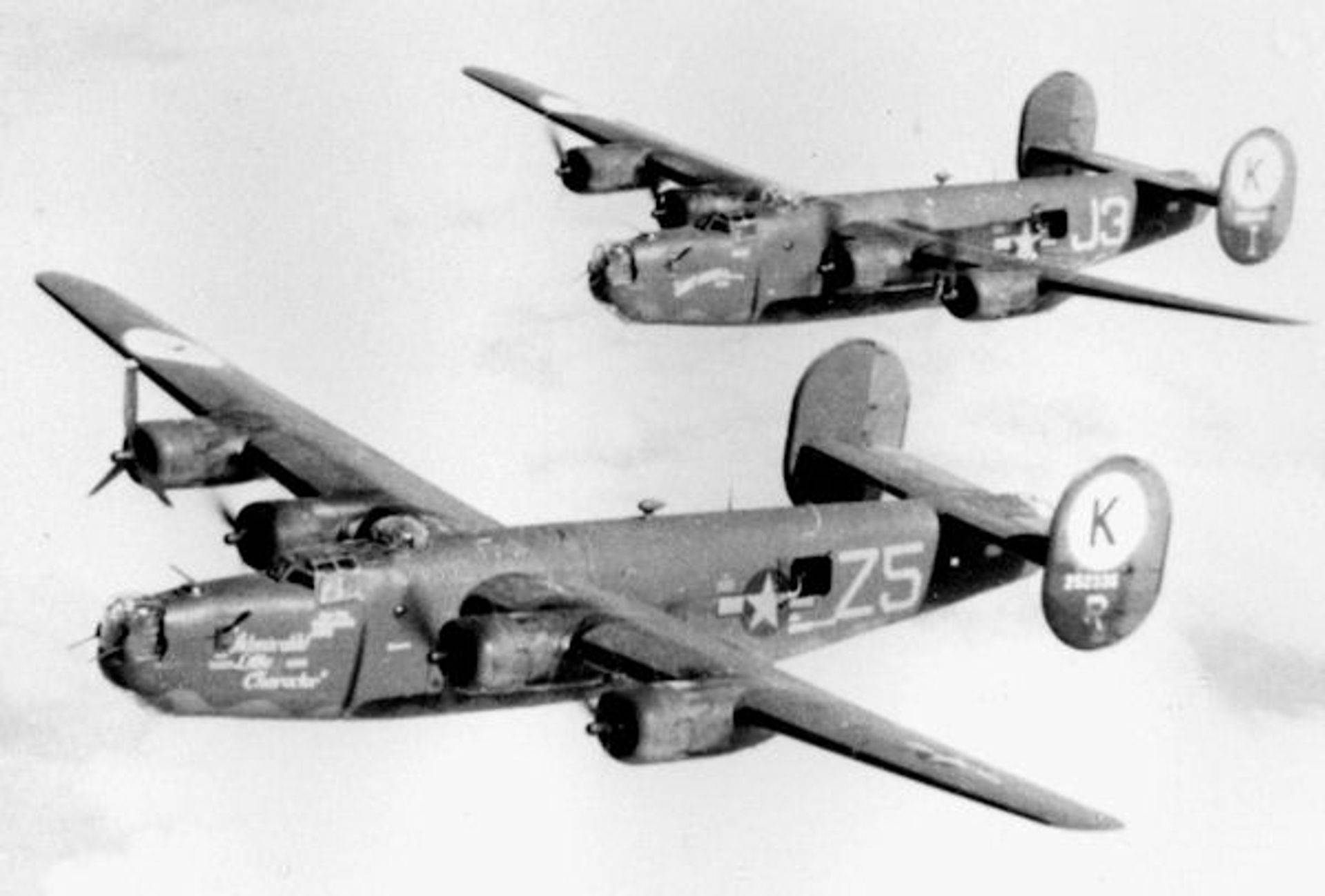

| 25-Apr-44 | MANNHEIM A/F | 27 | 10 | 42-52335 | R | Z5 | 21 | ADMIRABLE LITTLE CHARACTER | SHOT DOWN, FIGHTERS |

“Dear Folks”

The following is an article published in The Birmingham News on April 28, 1944 – three days after Combs’ and his crew were shot down. It is likely that news of the loss of the crew had not yet reached anyone back home.

EDITOR’S NOTE – The following letter was written by 1st Lt. J. H. Combs, Jr. from England where he is pilot of a B-24 and squadron commander. Because of its general interest, Lt. Combs’ parents are sharing it with others.

The News is anxious to receive other such letters for use in this column and invites recipients of them to send them to “Dear Folks Editor” in care of The Birmingham News, Birmingham 2, Ala., along with information regarding the writer and identification of the receiver.

Lt. Combs’ parents have resided in Birmingham for the past six years. He was graduated from Ramsay High School and attended Birmingham-Southern College. He has been in service two years, serving for three months overseas.

* * * * *

Dearest Folks:

I received the letter you wrote on March 8. That was the day we flew the “Big B. Number 4.”

You asked me about the reliability of the news casts when they say, “so many planes failed to return.” They are quite true. In fact, the reports show a 2 percent loss each month.

We sent five or six hundred ships over every mission; we ran an all-time high of 22 missions this month. So we should be minus 250 or 260 ships. We aren’t though. In fact, the loss is below 100 by quite a few. Let’s look at this “10 planes failed to return.” What does that sentence really mean? That means that out of 1,000 airplanes over Germany, 10 planes did not come home. Ten planes. Let’s say three were fighters, one was shot down, the pilot killed; one was shot down, the pilot got out in a chute; one ran out of gas and landed in the drink and had to be picked up by the patrol. There we have three of the 10 missing planes, with one man missing.

What about the seven bombers missing? Let’s look at the Fredrickshafen [sic] mission. Twenty-two bombers failed to return. Fourteen of those bombers struggled into Switzerland and landed. A couple were shot down and the crew had to bail out. One “got it.” (That is, it was hit directly and blew up.) The others just disappeared. Now we see where a lot of this “failed to return” doesn’t mean the men were killed. On the contrary, about 80 percent of the ships that “failed to return” landed okay – or the men bailed out and are okay. Now we take the bunch that “jumped out” over enemy territory. They will either be made “prisoners of war” or they will “evade”.

Much to our pleasure a great many of the boys can “get out” one way or another. Those who are taken prisoners are safe and treated quite well. How they escape is something else. You never know until you have to escape, I guess. A French “slave worker” got out after we hit Berlin on the sixth. He said, I take this from the newspaper, we hit some very important war factories employing 25,000 French workers. After the bombing was over, SS men (German Military Police) patrolled the streets in the area armed with machine guns. They fired on any group or bunch who looked hostile or even suspicious. It was plain riot killing as has happened after previous attacks. It shows the fear of the German Army against revolt and riot of the French. By shooting as they did, several innocent German citizens were killed along with the Frenchmen. He went on to say that after they had collected their wits (they being the Germans) they told the Frenchmen to go anywhere they could find a job, we can no longer take care of you, or employ you in the Berlin area. At this point the story teller went into Sweden and over to England.

This is a common occurrence these days. The German people have marvelously high morale considering the thousands of homeless people in Germany. We will be a long time beating their morale – civilian morale, I should say. The total collapse of industry and transportation is close at hand and has been accomplished in several important areas. We know that the army is having more trouble because of captured mail and prisoners who have surrendered. They all complain of the terrible “set back” on all sides. One pilot who flew his plane over to an Allied base and gave up, said he couldn’t stand it any longer, seeing whole squadrons of German planes go out to meet us – never to return. Other prisoners taken to the States couldn’t believe their eyes when they saw New York still standing. They had been told that the Luftwaffe had destroyed the city on large scale operations. So it goes.

You say now – well, have we hit Hamburg, Berlin and other cities? Well, Hamburg is a place that used to be a city. It is completely destroyed. I venture to say there isn’t a building standing. As for Berlin, I wouldn’t give you $10 for the whole city as it is now.

We are winning the war. We are crushing German production. We are abolishing the German Air Force. The day is coming when they won’t have one tactical aircraft to put in the air. If they continue for many more months, the German population will be a minor part of the living people in Europe. I can see the end of the “European situation” closer every day.

Loads of Love,

HARLEY Jr.

Courtesy: Elaine Combs

B-24H-15-FO 42-52335 Z5 R “Admirable Little Character“

“Admirable Little Character” in the foreground with No. 4 prop feathered. “Last Card Louie“ is in background.

(Photo: Geneva Schulze)

Caption: “Remains of B-24 near Marne Canal, France“

(Photo: Don Church)

Grave site of Crew 44 Killed in Action

The wooden crosses for Charles Bieber, Richard McCarthy, Clayton Miller, and Harry Tamboer in a French Cemetery

(Photo: Don Church)

1Lt John H. Combs German ID card

Local Airman Tells Of Playing “Cops And Robbers” with SS

From an undated news article

There’s something about the story that sounds like boys playing cop and robber through fields outside Leeds of Brighton or Tarrant. That is, if you’d omit the 90mm shells and answering 88s that freight-trained over their heads while they crouched in a farmhouse cellar. And if you left out Sagan, and a forced march from Sagan to Muskau, trudging through the snow in frozen and cracked boots. Also you’d have to skim over the fact that if two of those boys who slipped out of a barn last April 6, and walked during the nights toward what they hoped were American lines and hid during the days I thick scrub pine, had been caught by SS troops instead of the Wehrmacht – well, John H. Combs, Jr., of Homewood, wouldn’t be telling the story today.

But here is Johnny Combs to tell his own story of escape from the Germans. “Back in January when the Russians were moving up from the east to the Oder River, orders came to the prison camp at Sagan that prisoners were to be marched to Nurnberg. It was Saturday. It had been snowing and the temperature was down to 20 degrees below zero. At midnight they started us out on the march.”

All night long through the heavy snow the American fliers and the other prisoners marched. Came daylight, the Germans not wanting to be caught on the road by strafing American planes, stopped in a town. While the German guards went inside for warmth, food and rest, John Combs and the other “kriegies” stayed outside in the streets and sat or lay in the snow. Sunday night they marched all night again. By then their shoes, frozen solid, would crack open as they walked.

“When we marched into Muskau a lot of the men just passed out from exposure, cold, hunger and just plain exhaustion. Their arms would just curl up and they’d fall over. All of our feet were frozen.”

Two days they stayed at Muskau and then moved on to Spremburg—still marching. “We just couldn’t walk any further than Spremburg, so the Germans got some boxcars. The capacity of those cars was 40, but they piled 50 in each car.” The prisoners rode jammed in the boxcars for two days and two nights.

“At Nurnberg, we bivouacked a mile and a half from the main choke point of the German railroad.” For the American airmen prisoners this meant sitting for two months, February and March, under the heaviest bombing any German city had yet has while their fellow airmen flew over twice a day, dropping bomb-loads dangerously close. “the Germans started moving us out on April 6 and that night while we were bivouacked in a barn, West (Lt. Sam West, of Austin, Texas) and I just walked away.”

That part sounds easy. But there followed eight days and eight nights without food, hiding behind sick young pine scrubs during the day and walking at night. “We could steer by the stars and just before dawn we found a place to hide and rest for the day.”

“But then the Wehrmacht caught us.” Young Combs said it could have been worse. “The SS troops didn’t just turn you back into a prison camp. But the Wehrmacht did. We were sent back to Nurnberg. The Luftwaffe had moved out and gone to Moosburg and had taken the whole camp with them except a few Wehrmacht troops and the Serbian general staff who were prisoners. We were put with them.”

At the end of the week, by which time other escaped prisoners of war had joined their ranks, orders came through that prisoners were to be marched out. The orders didn’t say how many or where they were to be sent. “If the Germans get orders for ‘prisoners’ to be moved they have filled the order if they move two. So lots of the fellows played off – said they were too sick to march. We knew the Americans would soon take Nurnberg so left as many as could get by with staying, but to keep the Germans happy 16 of us went along.”

So the 16 prisoners and their 15 Wehrmacht guards set out and it’s an even bet as to which gave the other more trouble. “We kept complaining about not being able to walk, so they got a hay wagon and horse for us,” ex-PW Combs related. “We knew American troops were fighting around Nurnberg, so we finally put our cards on the table, and I, being ranking officer in our group, told the German first lieutenant ‘Why don’t you surrender to us?’ He wasn’t much for it, but the way we finally worked it out, we’d march just a few kilometers (about eight miles) a day just so we’d keep moving and it would look like we were going some place. That was in case any SS troops should turn up. The SS would have shot us all – prisoners and Wehrmacht.

“We also made an agreement with our guards that when we got to a German town and they would go in and commandeer food in the name of the Reich, that they would bring it back and divvy it up with us. We’d tell them that they’d better look after us ‘cause the Americans were coming.”

But the German guards didn’t need their prisoners to remind them that the American Army was near. They could hear the American artillery. And one evening during the round-in-circles march, German troops started moving down from Nurnberg through the little town where the wandering group had bivouacked.

“Always before this German soldiers we had seen had their ties on, their shoes slick, their equipment polished, but these came through that town looking beaten, pulling their clothes and personal effects in little wagons. And these weren’t refugee civilians, but the German Army getting the heck out of there. There was a Frenchman with us and he said that in the three years he had been in Germany, he had never seen the Germans so completely beaten as they were then. We went on into a farm that the Germans took over, and we bivouacked there for three days. To the south of us was the town of Ickstadt. American troops were to the north.

“On the nigh of April 24, the Americans laid down an artillery barrage that went right over us. We stayed down in the cellar together with our guards and some refugees from the town. Some of the shells landed within 25 yards of the house.”

Those shells landing close might have had “made in America” or “made in Germany” stamped on them. Shells were soon going both ways. “We’d hear the American 90’s go over. Then we’d hear the 88s come back. The Americans knocked out the German emplacement before the Germans got them. We figured the Americans would start a mass attack at dawn and then they would find us. When morning came everything was quiet.”

Not knowing what they would find outside, the prisoners and their guards emerged from the farm house. “And there, lined up as far as you could see were GI trucks. They had moved in without a fight. The German first lieutenant got a piece of white cloth from inside the house and he and 14 other guards surrendered to us – their prisoners.”

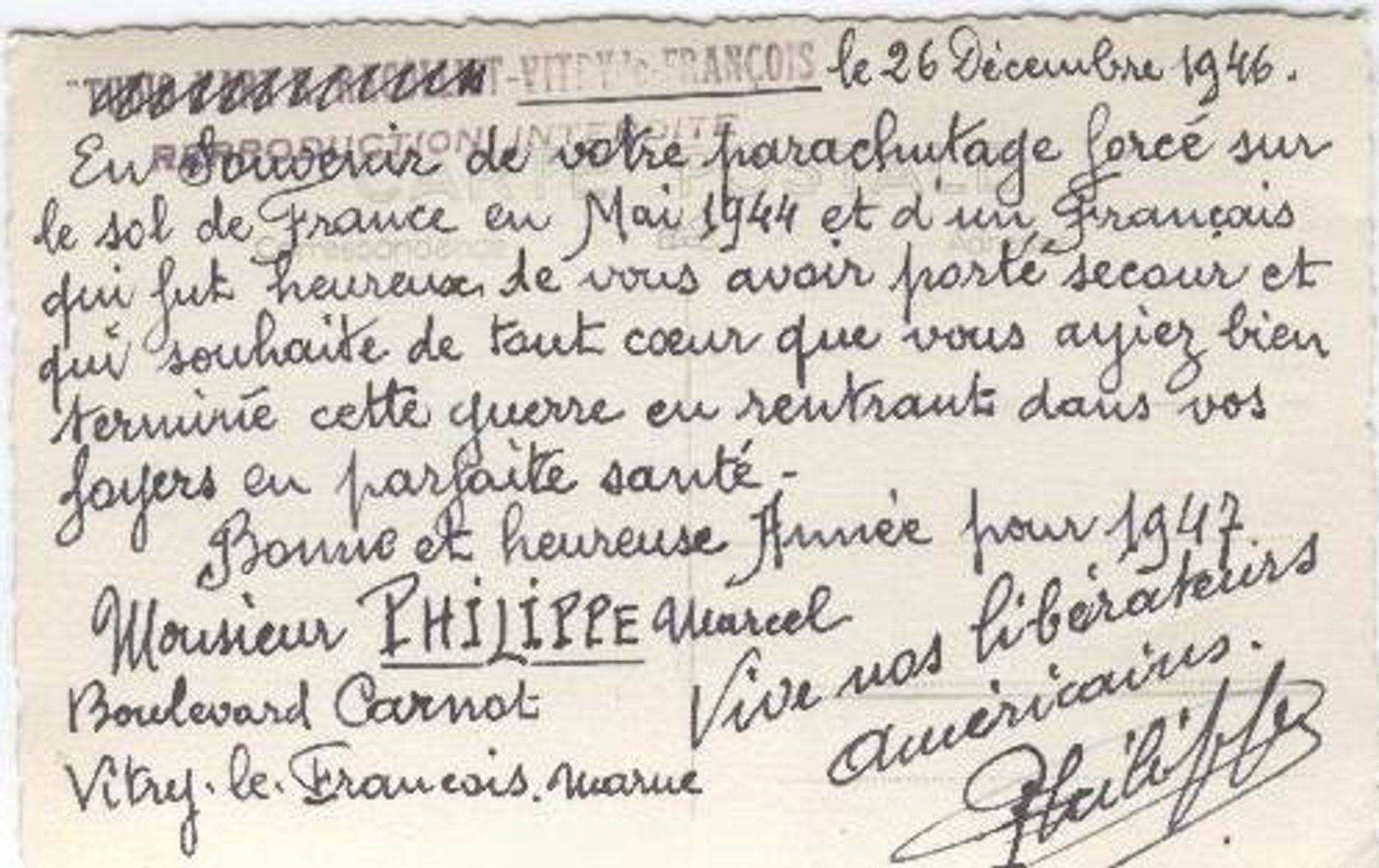

Postcard from France – Christmas 1946

Translated as follows

Vitry-le-Francois (name of French town), 26 Dec. 1946

In memory of your forced parachute fall onto French soil in May 1944 and of a Frenchman who was happy to give assistance, and who wishes with all his heart that you have ended this war successfully and have returned to your home in perfect health.

Wishing you a good and happy New Year in 1947.

Mr. Philippe Marcel

Boulevard Carnot Long live our American liberators!

Vitry-le-Francois, Marne /Signed/ Philippe

(All items on John Combs courtesy: Elaine Combs)

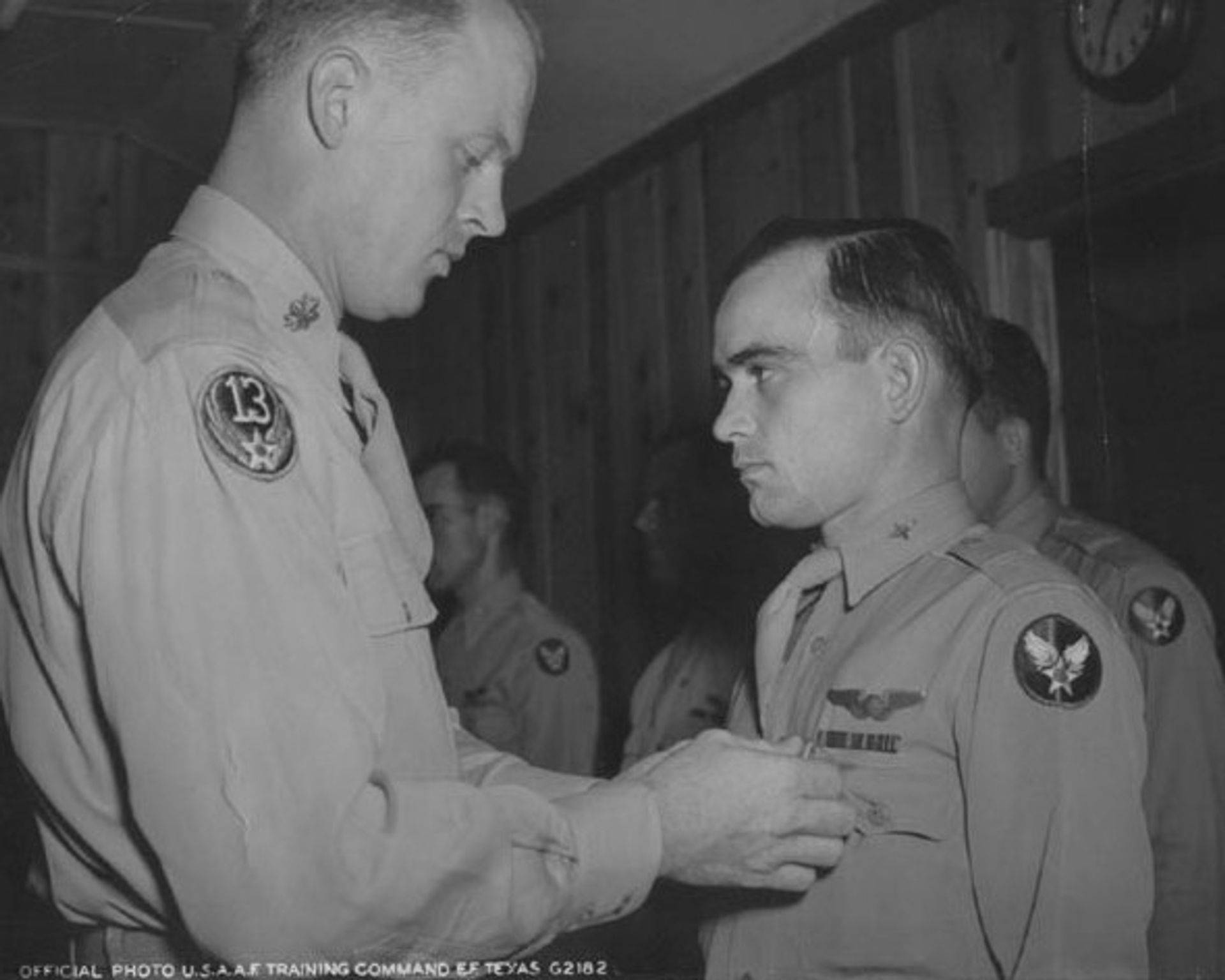

Capt Eugene Hoag – Navigator

Navigator Eugene Hoag being decorated

(Photo: Don Church)

Eugene Hoag was recalled for the Korean Conflict. He was assigned to the 372nd Bomb Squadron stationed at Kadena Air Base in Japan. On February 1, 1952, he was the navigator on board B-29 44-61908 on a routine formation flight. They collided with another aircraft, disappeared through the clouds and were lost. The other B-29 landed safely back at base.

Portion of Accident Report 52-2-1-2

AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT INVESTIGATOR’S REPORT

B-29’s 6392 and 1908 had been cleared for a local formation flight at 15,000 feet msl. 6392 was flying lead and 1908 was flying left wing position. A turn had been completed and 6392 advised 1908 to take over the lead. Very shortly thereafter the left scanner of 6392 reported to the A/C [Aircraft Commander] that a B-29 was coming in and about the same time the impact was felt. Lt. Thompson, A/C of 6392 and flying in the left seat looked, and saw through his window, his #1 propeller strike the right wing tip of 1908.

At this point there is varied opinion among the crew members as to whether 1908 came in over the wing of 6392 or up from below. It is the opinion of the Investigator that 1908 came in from below. It has been stated by the A/C that 1908 then broke to the right and downward. If 1908 had come in from above it is probable that immediately after the impact 1908 would have rammed 6392.

The two aircraft had been flying approximately 700 to 1000 feet above the undercast and after the collision, 1908, in a descending turn to the right, entered the undercast and was not seen or heard from again although the aircraft was called repeatedly after the accident.

B-29 6392 then feathered #1 propeller and returned to Kadena Air Base with no difficulty.

Immediately after 6392 landed, the Investigator thoroughly questioned the entire crew on all phases of their flight. There were no malfunction of any engine or component on 6392 prior to the accident, and 1908 at no time indicated having trouble. Both crews had been properly briefed prior to departure and pre-arrangements had been made for formation flying. The crew of 6392 had been using their oxygen system and it was functioning properly. Whether or not the crew of 1908 were using their oxygen system is unknown, however, it is assumed that they were, and the incident is not considered attributable to hypoxia.

As far as can be determined by the Investigator, there is no obvious reason why 1908 collided with 6392, and any conclusion would be supposition.

Air Rescue Service was alerted immediately and an extensive search was conducted, also crash boats were dispatched to the area. An oil slick, presumably from 1908, was located approximately 10 miles NW of Yontan Beach (attached photostat of map) and first day’s search was centered around the oil slick. No wreckage was recovered other than parts of aircraft lining and an oxygen bottle. A few small bits of human flesh and clothing were recovered, however, identification of personnel or the aircraft has been impossible. The depth of the ocean at the point where the oil slick was sighted prohibits the use of diving personnel to definitely identify the aircraft. Until such time as positive identification might possibly be made, the crew and aircraft are being officially carried as missing.

It is to be noted that the accident occurred at 15,000 feet and extensive search has failed to locate any survivors thus indicating that in all probability no parachutes were successfully used by crew members of 1908.It is the opinion of the Investigator that damage to the right wing tip and aileron of 1908 was sufficient to render the aircraft uncontrollable, thus causing the aircraft to enter a spin or very tight spiral and creating sufficient centrifugal force to prevent personnel from bailing out. The possibility of a partially controlled ditching has been excluded because the small amount of wreckage and parts of bodies recovered indicates partial or complete disintegration upon impact. The spiral or spin could not account for this disintegration whereas a partially controlled crash would not have been so complete.

Weight of the aircraft, weather or material failure are not considered factors in the accident.

/Signed/

Robert R. Snook

Captain, USAF

Acft Acc Inves Off

S/Sgt Clayton L. Miller 37314729, Gunner