Crew 33 – Assigned 753rd Squadron – October 25, 1943

Shot down April 22, 1944 – MACR 4180

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Pos | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1Lt | George N Spaven, Jr | 0531028 | Pilot | 22-Apr-44 | KIA | Buried Hoetmar, Kreis Warendorf |

| 2Lt | Robert L Zedeker | 0811278 | Co-pilot | 22-Apr-44 | POW | Stalag Luft III |

| 2Lt | Peter Kowal | 0810990 | Navigator | 22-Apr-44 | POW | Stalag Luft III |

| 2Lt | James F Mortinson | 0682501 | Bombardier | 22-Apr-44 | POW | Stalag Luft III |

| S/Sgt | Cedric C Cole | 36721017 | Radio Operator | 22-Apr-44 | POW | Stalag 17B |

| T/Sgt | James H Wedding | 33192630 | Flight Engineer | 22-Apr-44 | POW | Stalag 17B |

| S/Sgt | Lawrence J Scheiding | 16092460 | Ball Turret Gunner 2/E | 22-Apr-44 | POW | Stalag 17B |

| Sgt | DeSales A Glover | 13131261 | Armorer-Gunner | May-44 | RFS | Return to ZI-Discharge 16 yrs old |

| S/Sgt | James L Fittinger | 39277261 | Waist Gunner | 22-Apr-44 | POW | Stalag 17B |

| S/Sgt | Herman A Peacher | 17159837 | Aerial Gunner 2/E | 22-Apr-44 | POW | Stalag Luft 4 |

Crew 33 started out in Tonopah with 2Lt Joseph M. Mahan as its pilot. Shortly before leaving the States, Lt. Mahan requested to be removed from flying duties and 2Lt George N. Spaven took his place. S/Sgt Everett M. Cayford, waist gunner, is pictured with Crew 33 and also with Crew 20, pilot Robert Lamb in the same Squadron. Apparently he flew with Lamb’s crew in combat. When that crew was transferred to the 389th, Cayford went with them and was shot down with them on July 31, 1944.

Taking Cayford’s place in the waist was Sgt DeSales Glover. He flew six combat missions in March and April before his true age of 16 was revealed to his fellow crew members. He had enlisted at the age of 14. He was sent back to the States on May 1, 1944. Sgt Robert L. Allin now joined the crew and his first mission took place on April 22, 1944 to Hamm, Germany.

Spaven’s crew did not have a easy time of it in their brief combat tour of twelve missions. On March 8, 1944 the crew flew their second mission to Berlin to hit the Erkner Ball Bearing Plant. Upon their return to England, the crew believed their fuel was running low and they came down at Watton, crash landing their ship in order to avoid hitting the caravan at the end of the runway. All crew members (a number of them borrowed from Crew 25) were unhurt.

On twelve missions flown, Spaven’s crew flew ten different B-24s from the 753rd Squadron. Their final mission was flown in Flak Magnet on April 22, 1944 to Hamm, Germany. On this day the Eighth Air Force took off late in the afternoon and returned after dark. The 2nd Bombardment Division, trailing the attacking force, returned in darkness and was attacked over England by ME-410 night fighters. Seventeen Liberators, two from the 458th, were shot down over Norfolk. This did not concern Spaven’s crew very much, as their B-24 had been shot down prior to the target by Major Heinz Bar. Flak Magnet was Bar’s 200th aerial victory. (See detailed account below)

Radio Operator S/Sgt Cedric Cole, wrote an account of their last mission, Crew 33 and Flak Magnet: Their Finest Hour that can be found in the Stories page of this website.

MACR 4180

Spaven’s A/C was hit by flak at approximately 1938 hours SW of Hamm. The #2 engine caught fire and A/C fell out of formation. Four chutes were seen. A/C then was brought under control and Spaven regained altitude and rejoined formation. After an undetermined period of time, A/C was observed to leave formation and head west, still under control.

Missions

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 03-Mar-44 | BERLIN | 2 | 1 | 41-29286 | -- | J4 | 1 | UNKNOWN 011 | |

| 06-Mar-44 | BERLIN/ERKNER | 4 | ABT | 41-28735 | S | J4 | -- | UNKNOWN 005 | ABORT - NO SORTIE |

| 08-Mar-44 | BERLIN/ERKNER | 5 | 2 | 41-28729 | G | J4 | 2 | UNKNOWN 046 | CRASH LAND STA 505 |

| 15-Mar-44 | BRUNSWICK | 7 | 3 | 41-28733 | P | J4 | 2 | RHAPSODY IN JUNK | |

| 18-Mar-44 | FRIEDRICHSHAFEN | 9 | 4 | 42-100431 | B | J4 | 4 | BOMB-AH-DEAR | CHAMBERLAIN Cmd P |

| 23-Mar-44 | OSNABRUCK | 12 | 5 | 41-28705 | H | J4 | 11 | YE OLDE HELLGATE | |

| 24-Mar-44 | ST. DIZIER | 13 | 6 | 41-29300 | M | J4 | 11 | LORELEI | |

| 05-Apr-44 | ST. POL-SIRACOURT | 16 | 7 | 41-28733 | P | J4 | 9 | RHAPSODY IN JUNK | |

| 08-Apr-44 | BRUNSWICK | 17 | 8 | 42-100341 | A | J4 | 6 | SATAN'S MATE | |

| 09-Apr-44 | TUTOW A/F | 18 | ABT | 41-28721 | L | J4 | -- | DOWNWIND LEG | ABORT |

| 11-Apr-44 | OSCHERSLEBEN | 20 | 9 | 41-28733 | P | J4 | 13 | RHAPSODY IN JUNK | |

| 18-Apr-44 | BRANDENBURG | 22 | 10 | 41-28721 | L | J4 | 14 | DOWNWIND LEG | |

| 19-Apr-44 | PADERBORN A/F | 23 | 11 | 41-29276 | T | J4 | 8 | URGIN VIRGIN/ROTTEN SOCK | |

| 22-Apr-44 | HAMM M/Y | 25 | 12 | 41-29273 | Q | J4 | 21 | FLAK MAGNET | FTR - FLAK & FIGHTER |

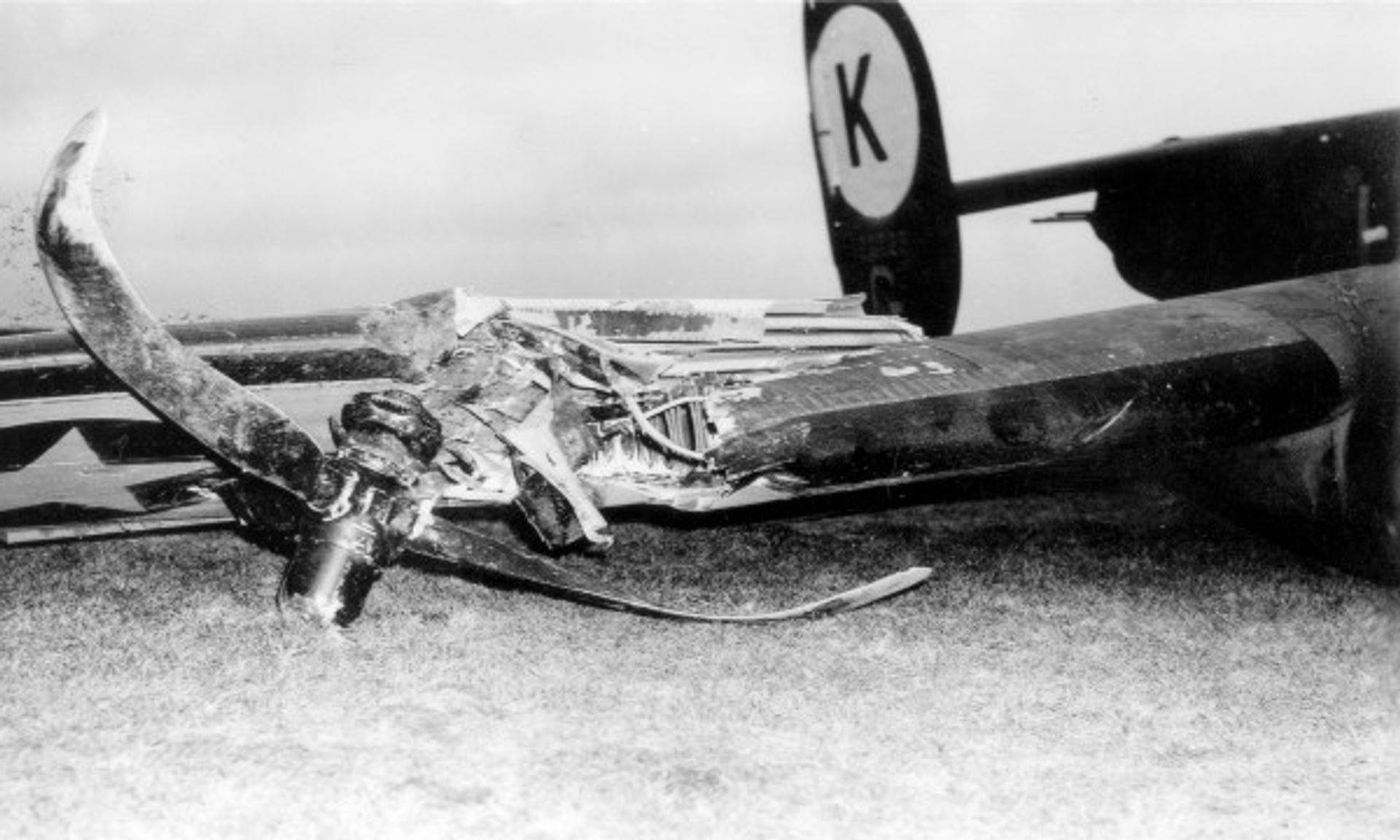

Spaven Crew Crash landed at Watton March 8, 1944- AR 44-3-8-509

B-24H-10-DT 41-28729 G J4

DESCRIPTION OF ACCIDENT

Upon returning from a mission, pilot brought the plane down through an overcast on three engines and broke out over Watton. The pilot, believing that the plane was about out of gas, circled the field for a landing.

Pilot claimed that all the engines cut out on the base leg. On the approach, number 4 engine cut in and started to turn the plane to the left toward the caravan and the hangers. In order to avoid hitting the caravan, the pilot tried to pull the plane up and stalled out. The plane fell off to the right and washed out the right landing gear, damaged number 3 and 4 engines and propellers, right wing, and the fuselage. Plane was categorized as E1.

Although this forced landing resulting in the accident and damage described above was caused by the lack of fuel in the man fuel tanks immediately available for engine operation, subsequent investigation revealed that the Tokio tanks contained 250 gallons of gasoline.

Fuel transfer pump was checked for operation, and as much as possible of the fuel transfer lines was visually inspected; there were no defects found.

Attention is invited to the enclosed statement of T/Sgt Willis A. Foster reference, his efforts and procedure in transferring gasoline from Tokio to main tanks. Procedure followed by the Sgt was correct and would lead him to believe, as he did, that all gasoline had been transferred to the main tanks. The committee, finding no mechanical defects in the transfer system nor errors in the process of affecting transfer of the gasoline, was unable to place responsibility for the accident.

Signed

William H. Gist, Jr., Lt Col., AC

A.A. Novitzkie, Jr., Capt., AC

Henry R. Miller, Jr., 1st Lt, AC

Statement of Pilot

Short of gas over Channel. Send S.O.S. after lost #3 engine and #4. We transferred fuel from #1 and started #4 – let down through over cast and broke out over Watton. Circled to runway and lowered gear – on base-leg all engines quit. Had to stall in to clear wires and on last of final, #4 engine cut in and slewed ship towards caravan. Pulled up and had no power – stalled in on right wheel — landing gear gave way and ship made 180°. No one hurt.

Sgt DeSales A. Glover

From the Associated Press

Sgt DeSales Glover who was decorated after his sixth mission over Germany is coming home from the wars at the ripe old age of 16. A Liberator gunner, he was grounded in England recently when the Army discovered he was under age, the Associated Press reported today. His mother, Mrs. John J. McGrath, of 237 McKee Place, Oakland, said he enlisted when he was 14 and a freshman at Connelly Trade School. Mrs. McGrath, the wife of a retired Oakland traffic policeman, said her son was large for his age.

She added: “He was five feet eight when he joined, and the following August, when he came home on his only furlough, he stood five feet eleven. He came home from school one day and said he wanted to enlist. I though he was only kidding, but he said he had tried to enlist in the Navy. Then he tried for the Air Corps. I think he told them he was 17 or 18. I signed the papers for him. He wanted to do his share in the war. He liked it after he got in, especially after his squadron flew the Atlantic.” In England, Sgt Glover commented: “I hate to quit the Army and give up flying. But when I’m old enough I hope to re-enlist for pilot’s training”.

Sgt Glover was graduated from the gunnery school at Tyndall Field, Florida, in the same class with Capt. Clark Gable, and trained in the United States with both Liberators and Flying Fortress groups.

See Stories Page: A Tale of Two Gunners

Saga of Flak Magnet

Night of the Intruders

First-hand accounts chronicling the slaughter of homeward bound USAAF Mission 311

The following account of Crew 33 on April 22, 1944 is from Night of the Intruders by Ian McLachlan, who very kindly granted permission to duplicate certain portions of his book detailing the loss of 458th crews on this website.

Guiding the second 467BG section was bombardier First Lieutenant John K. Gile who sighted for range and deflection on what seemed to be goods wagons in the yard’s southern end. A two-minute bombing run at 23,500 feet on A5 autopilot went smoothly for his 14 ships, with only minor problems encountered. Another rack malfunction delayed release from Lieutenant Goldsmith’s ship but at least they fell in the target area, whereas those from Lieutenant Perry’s aircraft merely started fires in the woodland because his bomb bay doors stubbornly refused to open in time. Most crews were pleased with their bombing results – but, departing from the target area, the 467BG realized they had lost the 96CBW. Careful calculations by Second Lieutenant Morton Deutsch, the lead navigator, established that continuing their southerly course would see them rally with the 458BG near Koblenz. His flight record was used for both navigational and general observations and, at 1950 hours, he noted the sighting of a parachute. Other Liberators came so close to the hapless airman that they almost spilled his parachute. Like Deutsch, their crews had no way of knowing the descending flier was one of four from a 458BG Liberator about to become the 200th “kill” for the famous Luftwaffe fighter ace, Heinz Bär of JG1.

Almost minced by the Liberators, Staff Sergeant Herman A. Peacher (left) swung frighteningly in his harness, buffeted by prop wash and wincing as another on-coming bomber swerved to avoid him. As it thundered by, Herman longed for the security of his own tail-turret, homeward-bound as he had been 10 times before. True, there had been some rough trips, but Herman’s faith in his pilot, First Lieutenant George N. Spaven Jr., remained unshaken – even now he could hardly believe what had happened. Twice before, George had pulled their damaged ship home against almost impossible odds and his prowess inspired confidence within his crew. Today, that reputation helped settle their waist gunner, Sergeant Robert L. Allin, a replacement flying only his first mission. Spaven seemed indestructible. He had flown P-39 Airacobra fighters, twin-engined B-25 bombers and now handled the heavy B-24 with renowned deftness and sensitivity. But even Spaven had little choice against flak. Enroute to Koblenz, the inherent challenge in the name of their ship, Flak Magnet would prove fatally apt.

B-24H-10-CF 41-29273 Q J4 Flak Magnet

Southwest of Hamm, their top-turret gunner, Technical Sergeant James H. Wedding, saw on their starboard side a crippled B-17 being encouraged homewards by a fussy P-47. Tucking in near his charge, the “little friend” played cub-scout helping an old lady cross a dangerous street. Wedding was comforted by the sight. It was a relief to see their escort and he inwardly wished the pair well as he powered his turret to view forward. Suddenly, his concern became acutely personal – a box barrage of flak spattered the sky almost dead-ahead. Obscene red flashes in the evening sky left an ugly, black afterbirth. This first box was low, dead ahead – then a second, also dead ahead but high in the evening sky like devil’s spit in heaven. The third box ensnared them at 8, 11, 2 and 4 o’clock with the fifth shell hurtling diagonally right through the front of the bomb-bay into the center wing section, exiting unexploded just aft of the life raft hatch. It had bayoneted Flak Magnet, peeling back a large section of top-fuselage, the wound was grievous, with a torrential downpour of gasoline from three ruptured main fuel cells which fed their number two engine.

Flying off Flak Magnet’s right wing, the crew of Dream Boat saw the other B-24 veer alarmingly towards them then drop from formation, the gash in its upper wing clearly visible. Also evident was a haze of vaporizing fuel streaming from the stricken ship. Inside, some 500 gallons of gasoline pouring from burst tanks turned them into an enormous Molotov cocktail needing only one spark to eviscerate aircraft and crew in a fireball. Dropping swiftly from his turret Wedding operated the bomb door auxiliary control valve releasing clouds of fuel into the air behind Flak Magnet. The engineer’s actions would not only reduce the fire-risk but his reactions had to be rapid if Flak Magnet was to stand any chance of reaching home. Checking the fuel gauges, Wedding confirmed three seriously damaged tanks were empty and quickly set the transfer valves, started the bomb-bay booster pump and cross fed the number two engine from their undamaged tanks. By his calculations, they had lost about 550 gallons of fuel but he felt there was still sufficient on board to reach England. Further aft, the situation was more confused, causing reactions which helped seal the fate of Flak Magnet. The bombardier, Second Lieutenant James F. Mortinson, had hastened astern to get his parachute which he had left in the waist when boarding that afternoon. To do this, he had grabbed a portable oxygen bottle and disconnected himself from the intercom. Passing through the bomb-bay, he found the stench of high octane fuel almost overpowering despite his oxygen mask. Crawling into the waist, Mortinson saw Sergeant Allin gesturing at him to bale out and, being off intercom, Mortinson assumed Spaven had given the order to jump. Reaching for his parachute, he saw Allin hastily clip his own parachute on before leaping from the right waist window. The gunner’s action convinced the bombardier who soon followed, as did Staff Sergeant Lawrence J. Scheiding, emerging from his ball turret into this hectic scene.

Still in his tail-turret, Herman Peacher watched with mounting alarm as leaking fuel streamed off the starboard stabilizer. Like many Liberator tail gunners, Herman kept open his turret doors. The blast of air from the waist was now moistened by a spray of neat fuel sucked in the left waist window, and dousing the bomber’s interior. Glancing round, Herman saw a figure vanishing through the right waist window, glimpsing only a pair of vanishing feet. Herman had not heard the bale-out command but the empty fuselage told him everyone was leaving, his intercom must be out. Hunching into a ball, he released the power control handles for his turret and rolled backwards off his stool on to the fuselage catwalk. Eighteen months ago he had been building B-24s in San Diego so he knew how to move fast inside one. As he rolled, his oxygen mask and microphone tore off and the action snapped the quick release tabs on his flak jacket which fell away as he stood up. Inside the fuselage, he saw gasoline streaming along the aluminum corrugations and pouring out of the camera hatch. The ship was an airborne tinder-box.

Flak Magnet (upper right) trailing fuel vapor after flak holed their fuel tanks

(Photo: Harold Armstrong)

Grasping his parachute, Herman clipped it on as he hastened to the camera hatch. Flak Magnet seemed empty and could explode at any second. Reaching the hatch, he forced his way through, only to be caught when the door snagged his knees. For an instant, Herman hung inverted beneath the bomber then, kicking himself clear, he parachuted into the path of Liberators lower down.

Having heard confused voices on the intercom, then silence and no response, Spaven told Staff Sergeant James L. Fittinger to leave his nose turret and check what was happening. All guns on Flak Magnet were now unmanned. Regaining control, Spaven now pulled back into formation, but being bound for Koblenz was increasing the distance home on their drastically depleted reserves of fuel. A few minutes later, other 458BG crews watched Flak Magnet shed its position and turn on a lonely western heading.

Other, less compassionate, eyes also saw the solitary bomber. Major Heinz Bär (left) of II/JG1, with Oberfeldwebel Schumacher flying wingman, hastened from his base at Stormede hoping to catch the unescorted B-24. On board Flak Magnet, Fittinger reported the absence of the bombardier and other gunner before setting about the release of their bombs by hand because the standard release and jettisoning systems had failed. This process entailed leaning over a vast, slowly moving panorama of German landscape while jockeying with a screwdriver to trigger the shackles individually. Breathing on a walk-round oxygen bottle, Fittinger, aided by Wedding and the radio operator, Staff Sergeant Cedric C. Cole, managed to free several bombs, each one increasing their chances. Cole had already attempted raising American escort fighters on the radio but heard only a mocking silence and felt he was of more use helping to dump their bombs. As the three fliers wrestled to release each ugly 500 lb burden, Bär’s FW190, Red 23, was closing rapidly from astern. Seeing the bombs fall from the Liberator, Bär assumed it was a “solitary scout” smoke marking the area. As a farmer’s son, Herman Peacher was adept at shooting crows on the wing and those skills translated neatly into his Liberator turret – but now it was empty. Diving on the B-24 from 5 o’clock, Bär expected retaliation from the tail turret. Judging his moment, Bär squeezed the firing button.

Fearful of anoxia, Fittinger had just requested a replacement for his portable bottle when Bär struck. A storm of destruction erupted in Flak Magnet. Cannon and machine gun bullets riddled the tail then strode towards the bomb bay. Miraculously, the first enfilade missed all three airmen in that section, even though some rounds ricocheted alarmingly off the bombs themselves. In the cockpit, the co-pilot, Second Lieutenant Robert L. Zedeker thought they had taken another hit from flak as exploding shells and a fury of bullets blasted pieces of Perspex, glass and aircraft into the cockpit.

Bär Necessities – Major Heinz Bar’s FW-190 “Red 23”

Painting by Aviation Artist, Charles Wissig

Again fate spared both him and Spaven, but Flak Magnet was doomed as the number two engine burst into flames. Even Spaven’s skills were overwhelmed. Yet the courageous pilot still had a duty to his crew and struggled to keep the B-24 level while they escaped. In the bomb bay, Fittinger had become groggy so Wedding and Cole snapped his parachute on for him then pushed him off the catwalk before themselves following him out into the void. Exerting all his expertise and sheer will power, Spaven kept Flak Magnet flying as his navigator, second Lieutenant Peter Kowal opened the nose wheel doors. From the shattered cockpit, Spaven and Zedeker could see Bär’s FW190 peeling off to the right as he swept around for a frontal attack. Releasing his seat harness, Zedeker hoisted himself clear, yelling at Spaven, “Let’s get the hell outta here!” Moving between the armored seats, the co-pilot saw that Spaven had not moved so he turned and slapped him on the shoulder. Spaven knew Zedeker could escape but what about Kowal? Hesitating, he nodded at Zedeker, released his harness and began leaving his seat. At that instant, Peter Kowal was about to pitch himself through the nose wheel exit but was startled as lines of spiteful red tracer cut viciously across his view of the green landscape beneath. The second they ceased, Kowal leapt for his life.

Zedeker was shielded by the back of his armored seat when the final torrent of fire tore into the cockpit. George Spaven had half risen. Then the instrument panel disintegrated and his body convulsed in a storm of bullets before slumping lifelessly across the controls. Zedeker threw himself clear. Seconds later, swinging beneath his parachute, he still hoped Spaven would appear but the once-proud Flak Magnet had become a funeral bier for its pilot. Wreathed in flames, the bomber dived steeply until an explosion blew both wings to pieces and the shorn fuselage carried George Spaven to earth near the community of Hoetmar. He was interred there the following day. His crew survived, although Herman Peacher broke his right ankle on landing in a field near Balve. Worse was to follow.

1Lt George N. Spaven

Spilling the air from his parachute, Herman awaited capture by people seen running in his direction as he descended. First to arrive was an armed civilian, ominously pointing his pistol at the injured aviator. Herman was unarmed. The 458BG discouraged the wearing of .45 automatics because being armed might provide an excuse for the Germans to shoot. Even so, someone yanked his helmet off and violently clubbed the back of his head. Still stunned, he was hauled up and manhandled roughly towards the village. During this agonizing journey, one of the four men carrying him took fiendish pleasure in tormenting the injured flier by deliberately manipulating his broken leg. In the village, he was interrogated by an ugly fat “Gestapo” female and a police sergeant before being taken to hospital in Balve where his arrival was at least treated with gentler curiosity. He was the first American shot down that close to town. Soon a variety of locals were trooping past his bed – school children, mothers, wounded soldiers and others curious to see this “terror flieger”. There was no serious attempt to treat his injured leg and, after two days, he was given a pair of crutches and ordered, unassisted, down three flights of stairs to a waiting truck. Every stair was a torment and, on reaching his transport, the excruciating pain had left him in a state of shock. Only pleading by a B-17 pilot on the truck got Herman a shot of morphine from the syrette in the first-aid kit on his parachute harness. It was three weeks before his leg was set but Herman has always considered himself fortunate that his only physical legacy was lameness in one leg.

A few minutes after Flak Magnet left formation, the continuing difficulties on board [Major Donald] Jamison’s lead ship finally forced him into relinquishing the lead slot at 1957 hours when he transferred command to Elwood T. Claggett. Navigating for Claggett was First Lieutenant I. R. Burton, who immediately gave his pilot a new heading towards their last resort target, the marshalling yards in Koblenz. Claggett’s bombardier, First Lieutenant James C. Smith was already preparing for the bombing run and found the optics on his bombsight were fogged. Unflustered, he calmly dismantled the unit, polished the glass and reassembled it before continuing his search for suitable reference points. An evening haze hid many ground features but rivers shone like strands of burnished silver. The confluence of the Rhine and Mosel in Koblenz provided a prominent feature and Smith synchronized on a distinctive section of river bank. Troubles with the C1 autopilot dictated a run on PDI and, nearing the target, Burton noted how the enemy appeared to “set off a field full of dummy bombs on east side of river opposite city”. Undeterred by this deception, the 13 laden bombers concluded a four-minute approach and released on the target at 1938. An almost flawless example of co-ordination was only slightly marred when Smith forgot to turn on the camera so lost his ship’s pictures of the attack. However, crews could now go home feeling something had been salvaged from the purpose of their mission.

Turning to starboard as it left Koblenz, the 458BG was 13 miles south of its briefed course and abreast of the Division formation. Earlier, Burton had used GEE transmissions as a navigational aid but then it succumbed to enemy jamming and was still of little use as the group withdrew. Their radio compass was “beaconed” – tuned for directional signal strength from known beacons – but Burton felt his radio operator, Technical Sergeant R. V. Hanson, a last-minute substitute, lacked the necessary lead-ship experience and training to reliably fix their position. However, the region’s many glistening lakes and waterways were distinctive markers as the 458BG merged with the course briefed that morning.

Eyewitness on the ground

“With interest I read the story of the B-24 Flak Magnet aircraft which was shot down during the raid on Hamm April 22, 1944. I am sort of a witness to that event. I was born and raised in Germany in the year of 1927 and at that time I was 16 years old. The plane was attacked by two German Air Force FW 190’s and one of the German pilots was none other than Heinz Baer who was one of the most decorated airman in the German Luftwaffe. The B-24 Liberator had lost two of its engines and obviously in deep trouble. This took place over the town of Oelde and here I witnessed how the first member of the crew jumped out and came down on his parachute. The plane finally came down in Hoetmar a little village about 10 miles from my hometown of Oelde. We had a little vegetable garden on the outskirts of town and the airman come down very close to that location.

“I ran over to see what an American airman looked like. The Nazi propaganda made them out to be vicious murderers, killing innocent civilians. What I saw was a very scared young man who probably thought the people would string him up. I guess it is very normal to have those thoughts. Just by coincidence a German Air Force officer being on furlough – he was a local boy and I knew him well – came over and told the airman not to worry as he was under his protection now – and nobody, but nobody – was going to harm him. I believe the guy felt a little better by now. After a while the city commander, an officer of the German Wehrmacht picked him up and I presume he was taken to Oberursel near Frankfurt.

“It has been 66 years since that time, I immigrated to Canada first in 1953 and came the United States in 1956. I settled in California — Los Angeles and worked most of the time for the motion picture industry most of the years for the Walt Disney Company in Burbank and after retirement moved into the lovely Napa Valley. Over the years I sometimes wondered whatever became of that then young American airman which I encountered in 1944 and at that time I never thought that I would be an American citizen also.”

Sincerely,

Franz J Huesman

The airman that Mr. Huesmann saw was most likely S/Sgt Fittinger. He was the only one to have been captured in this vicinity as this page from the German records indicate.