Crew 72 – Assigned 755th Squadron – October 21, 1943

Failed To Return – March 22, 1944 – MACR 3555

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Crew Position | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2Lt | Malcom W Dunlevie | 0745872 | Pilot | 22-Mar-44 | POW | Stalag Luft III |

| 2Lt | Charles G New | 0693696 | Co-pilot | 22-Mar-44 | POW | Stalag Luft I |

| 2Lt | David B Schulz | 0694609 | Navigator | 22-Mar-44 | POW | Stalag Luft I |

| 1Lt | Leonard W Blednick | 01011890 | Bombardier | 22-Mar-44 | KIA | Buried U.S. |

| Sgt | Dean W Pilkington | 16162066 | Radio Operator | 22-Mar-44 | POW | Stalag Luft I |

| Sgt | Edward L Storm | 12208869 | Flight Engineer | 22-Mar-44 | POW | Stalag Luft I |

| S/Sgt | Frank M Scimeca | 18151230 | Waist Gunner | 22-Mar-44 | POW | Stalag Luft I |

| Sgt | Delvin F Pederson | 19177619 | Waist Gunner | 22-Mar-44 | POW | Stalag Luft I |

| Sgt | Donald H Dugmore | 31270122 | Ball Turret Gunner | 22-Mar-44 | POW | Stalag Luft I |

| Sgt | John C Miller | 36298477 | Tail Turret Gunner | 22-Mar-44 | POW | Stalag Luft I |

Crew 72 trained in Tonopah as part of the 755th Squadron during the fall/winter of 1943. In January, along with the rest of the group, they embarked for the ETO using the Southern Route of travel. They were able to get in three missions before the Berlin raid on March 22, 1944. On this mission, engine problems forced the crew to bail out of their Liberator over Germany. Nine crew members landed safely and spent the rest of the war in POW camps. 2Lt Malcom W. Dunlevie ended up in Stalag Luft III and the rest of the surviving crew, including the enlisted men, went to Stalag Luft I near Barth on the Baltic. It is not known why the enlisted were sent to this “officer’s camp” at this stage of the war.

Due to equipment problems, 1Lt Leonard W. Blednick, bombardier, remained in the nose and was killed when the plane crashed. Blednick’s chute and harness both had snaps (one should have had rings) and he was unable to jump in time. What is most unfortunate is the realization by the crew afterwards that there was at least one additional chute that would have fit his harness in the waist area of the ship, but no one other than the navigator knew of his difficulties until after they had reached the ground. He was buried in the cemetery in Hover, Germany (about 20 miles east of Muenster) on March 24, 1944. His remains were repatriated at the end of the war, and he is buried in All Saints Braddock Catholic Cemetery, Soldiers Section in Pittsburgh, PA.

————————-

MACR 3555

[A gunner on Lt Zimmerman’s crew] saw Dunlevie’s A/C aproximately 1-1/2 hours after leaving target. He was flying to right and rear of Grant’s A/C at that time. Tail gunner (Cunningham) says he just disappeared. No one observed where or when.

Missions

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25-Feb-44 | DUTCH COAST | D2 | -- | 41-29359 | -- | J3 | D2 | TAIL WIND | Diversion Mission |

| 05-Mar-44 | BORDEAUX/MERIGNAC | 3 | 1 | 41-29331 | F | J3 | 2 | BLONDIE'S FOLLY | |

| 06-Mar-44 | BERLIN/ERKNER | 4 | 2 | 41-29359 | J | J3 | 1 | TAIL WIND | |

| 15-Mar-44 | BRUNSWICK | 7 | 3 | 41-29359 | J | J3 | 3 | TAIL WIND | |

| 22-Mar-44 | BERLIN | 11 | 4 | 41-28678 | M | J3 | 7 | UNKNOWN 002 | FTR - LOST OVER HOLLAND |

Dunlevie Crew in Tonopah, Nevada – Fall 1943

2Lt David B. Schulz – Crew 72 Navigator

The following is an account written by David B. Schulz [pictured at left as an Aviation Cadet]

Tonopah

Tonopah Nevada was an old, nearly abandoned mining town. Tonopah Air Base was built in the desert near the town. At Tonopah Air Base, B-24 crews first flew together in B-24s. The pilots had been in advanced B-24 flight school, but the rest of the crew had not been in one, not even the co-pilots. We trained together in old planes – no gun turrets, only swivel guns. We flew a lot of cross-country flights.

After a few weeks, we four officers went on a weekend pass to Reno. Because of civilian bus schedules, we lost a day getting there and most of a day returning. Our crew officers found that our pilot, Mac, was so arrogant and self-centered, that we never socialized with him again. We flew with him, but we didn’t want to be around him on the ground.

One day, all navigators were told to meet and to bring clothes for a one-week trip. We were loaded onto a bus and went to Los Angeles. It was on this trip that Sam [Scorza, Navigator on Crew 74] and I got to know each other. In L.A., we went each day to an observatory where the stars visible in the southern hemisphere could be projected onto the ceiling in their proper relationship and “movement”. We didn’t know where we were going, but guessed it would be south. In the 1940’s, the most accurate navigation was at night using the position of stars. This was especially true outside of the U.S.

Back at Tonopah, our crew one day, was assigned the exercise of air-to-ground firing of the ships machine guns. The swivel guns of the two waist gunners were in open windows. As we flew very low firing at ground targets, one waist gunner said his gun would cause a flume each time he fired it. Charlie, the co-pilot, went back to check it. Shortly, Charlie reported on the intercom that gasoline (100 octane) blew in his face. Mac immediately climbed to a higher altitude while the flight engineer checked. It was discovered that the gas cap behind number three engine was missing and gasoline was being sucked out by the airflow of the propeller. Number three engine was killed and the propeller feathered to stop its rotation.

Back we go to the field to land – except the wheels would not go down – the hydraulic pump was on number three engine. So, crank them down by hand. That had probably never been done on that old, obsolete B-24 and it couldn’t be done then. If we let the propeller start number three, will it backfire into a stream of gasoline? We all put on our parachutes before we climbed to 3000 feet and kicked it in. Nothing [bad] happened – the wheels could be let down hydraulically and we landed. The navigator and bombardier never stayed in the nose during takeoff or landing. We crawled through a passageway and stood on the upper deck behind the pilots.

Not much to do for entertainment in Tonopah. We never went back to Reno because of bus schedules. Sam and I went to town once or twice but nothing there. We mostly sat in the officers club for a couple of drinks. On the L.A. trip, one navigator had worked in the New York office and invited Sam and me to take a tour of the studio. We did, and had our picture taken with two “starlets”. I never saw them afterwards and I don’t think Sam did. We had a lot of work to do at the observatory, but one evening we went to a U.S.O. dance and had a good time.

Dave Schulz, Lynn Merrick, Unknown Officer, Leslie Brooks, Sam Scorza

San Raphael, California

We went by bus and by train to San Raphael, north of San Francisco across the Golden Gate Bridge. There we were assigned our own, brand new B-24. We checked the instruments and flew a long flight to calculate fuel consumption rate. Checked out everything. We had one Sunday off and I went to San Francisco with a W.A.C. (Women’s Army Corps). I think Sam did too, but we were not together.

En Route to ETO

Each crew flew separately, meeting at each destination. We only knew where we were going each day. The route was: San Raphael, CA – Palm Springs, CA – Big Spring, TX – Bossier City, LA – West Palm Beach, FL. We did not, however, go to West Palm Beach. After takeoff, Mac told me to give him a heading for Charleston, SC where his wife and son lived. We landed there and spent the night, then went to West Palm Beach the next day. From there we were supposed to go to Trinidad, but Mac asked for a heading to Cuba. We were not allowed off the base so we spent the night – then flew to Trinidad. From here we went to Natal. There may have been an intermediate stop in Brazil, but I don’t remember it. Because of weather, there was a back up of our crews in Natal and we were there for several days. From Natal we flew to Dakar, Senegal. This flight had to be made at night because the southern hemisphere stars were the only means of navigation. It was a long, all night flight, and we arrived just at daylight.

The next leg was to Marrakech and we carried another navigator who was familiar with the mountain pass we flew through. The last part of our overseas trip was the most difficult for me. Our final destination was Norwich, England and we had to fly westward in order to go around Spain and Portugal, head north, miss France, and then turn into England. This leg should have been flown at night also. We had no stars and only water below us. I had the pilot fly a drift pattern every hour to read the plane drift from the whitecaps of the waves, and we made it okay.

Horsham St. Faith, Norwich England

We arrived at the most beautiful air base I ever saw, with brick buildings and paved streets. We four officers were housed in two bedrooms of a large brick house, complete with a male housekeeper. We spent days practicing formation flying and attending briefings.

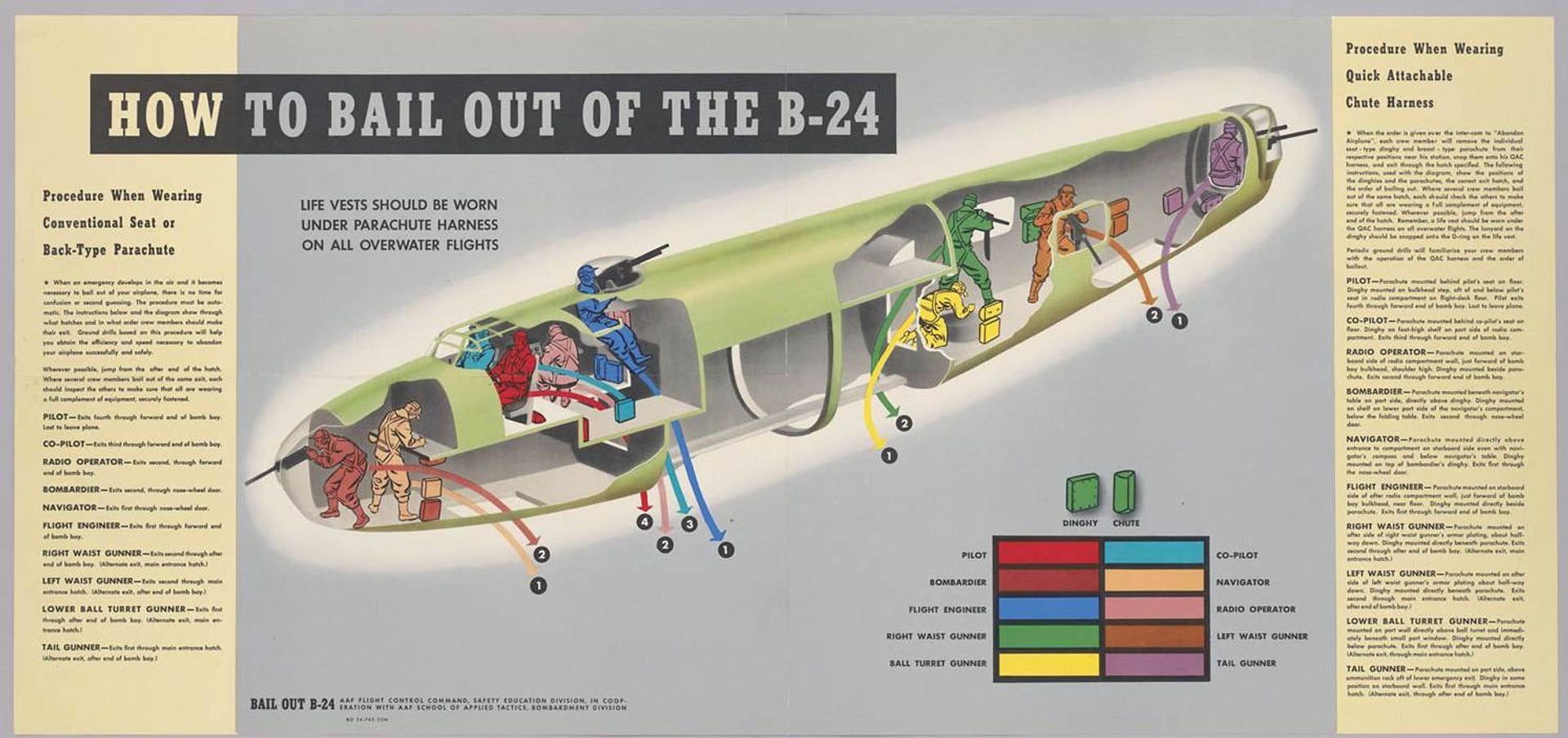

Wartime diagram showing positions and bail out exit for each crew member

Before writing about the first combat mission, let me explain the activities of the crew inside the plane. The pilots sat at the controls the entire flight, parachutes attached so that they sat on them. The navigator and bombardier rode in the nose section during flight. The flight engineer was the top turret gunner. The radio operator had a seat on the deck behind the pilots in front of his various radios. The waist gunners were at open windows and the tail gunner had a turret at his position. The belly gunner’s turret was retracted into the plane for takeoffs and landings. After takeoff, he would enter the turret and extend it out into space where he had 360° rotation. During takeoff and landing, gunners were not in their turrets and no one was in the nose section. After taking off and joining the planes already in the air and circling, the gunners would enter their turrets. The bombardier and navigator, who had been standing or sitting behind the pilots would go aft to the bomb bay, drop down a lever, and crawl through a passageway to the nose section, pushing our parachutes ahead. Note: Crew members other than the pilots wore a parachute harness and carried their parachutes, which could be snapped in place quickly.

In the nose section, the navigator had a worktable level with the pilot’s feet (which he could see). He had a “sling” seat he could attach or let drop to one side. Above his head was a Plexiglas dome to “shoot the stars” for night navigation (bomb runs, however, were made in daylight only). He had two bubble windows on each side of the nose to observe the ground below. All of us had an electrical outlet to plug in our heated suits and slippers.

All bombardiers were trained to use the Norden bomb sight to take the controls of the plane and sight in on the target on the ground to release the bombs at the proper time. With several hundred planes flying in close formation, if each bombardier was flying his plane separately, we would lose more planes from crashes than from enemy fire. Because of this only the lead plane used a bomb sight to drop his bombs and fired a flare so the others could flip a switch to drop their bombs. For this reason, the bombardiers became nose turret gunners with a toggle switch in the turret. Lennie, the highest-ranking officer on the crew (1st Lieutenant) was in fact only a gunner.

Before going on our first mission, Lt. Dunlevie, our pilot and captain of the plane held a meeting with the officers and told us, “Dave, you and Lennie are single. Charlie, you’ve been married only a few months, but I have a wife and son in Charleston, SC so it is more important that I get home than it is that you get home. And I’m going to get home.”

Five Missions

Number one was a short mission to bomb a German installation in France. We saw anti-aircraft fire, but no German fighter planes. The anti-aircraft fire shot explosive shells that on explosion scattered flak to damage planes or crew. The explosion at our altitude left a large puff of black smoke.

Number two was to Berlin which had never been bombed, but we found a cold front we couldn’t get over or go through. So we turned back.

Number three: we go to Berlin this time. The sky was black with anti-aircraft smoke. The lead navigator missed the target and the group commander made the decision to go around again to bomb the target. As a result, the 458th Bomb Group lost over 20 planes [this was the March 6th mission to Berlin, on which the 458th lost five aircraft (not 20), five was the most the group ever lost on one raid]. The commander called a meeting and apologized and said that it would not happen again.

Number four was back to Berlin again, but not as bad as number three. We had never been hit.

Number five (4-1/2?)

The briefing – before each flight, the briefing officer would unveil a map of Europe with routes marked on it for all the officers assigned to fly. On March 22 [1944], the mission was to Berlin. Instead of flying east over Holland, France, and Germany, we were to fly northeast; enter the Baltic Sea, fly eastward and enter Germany’s north coast going southeast to Berlin. Then [we would] head straight west back to England over Germany, France, and Holland in a “V” [formation] that is laying on its side. It wouldn’t take a third grader much trouble to figure out that on this route we would be as near to Sweden as we ever could. Sweden was a neutral country. Crews landing there were interned for the duration of the war, but were free inside Sweden.

The formation – The B-17’s always went ahead with the B-24’s following. The 458th, as the newest group in England, was the last of the 24’s and our plane was always “tail-end Charlie”. So there were no planes behind us.

The flight – As we crossed the German coastline, the propeller on number two engine suddenly began to “run away” or “windmill” which made a drag that caused us to lose speed and altitude. Immediately, Dunlevie said, “David, give me a heading to Stockholm.” I couldn’t do it. I did not have Sweden on my navigation map or any other map. I explained this and gave him a heading that would allow us to cut across the “V” and join the planes heading back after dropping their bombs. We met the other planes, but we were 3000 to 5000 feet below them and traveling slightly slower. Our radio operator began to call for our fighters (which were escorts for the bombers) to escort us back.

After heading home for half an hour, the tail gunner reported,

“Two planes coming up behind us.”

“Whose are they?”, said Dunlevie.

“I can’t tell”, said the gunner.

Immediately the alarm to bail out sounded. (There was a procedure where the pilot checks out the crew as they go to bail out – this never happened.)

I buckled my parachute to my harness and pulled the lever that dropped the nose wheel doors for our escape hatch. I turned back to see if Lennie was out of his gun turret. He was standing there with his parachute in his hand.

“It won’t fit”, he said.

Our chutes had rings that fit the snaps on our harness. Lennie had snaps on both. With the plane falling unattended, we didn’t have much time. I took Lennie’s parachute, turned it sideways and snapped one snap into another – not the best arrangement, but better than no parachute. At that time, the plane went into the clouds, which were at approximately 300 feet. I said, “Let’s go!”, and went to bail out. I looked back to see if Lennie was behind me. He was still standing in the same place and I didn’t have time to go back. I bailed out. Because I was falling so fast, when the parachute opened I was half unconscious when I hit the ground and was dragged across a field. Suddenly I stopped. When I got up, four farm workers had stopped the parachute.

“Polski.” one said, pointing to his chest. They were Polish prisoners. When I unbuckled my parachute and turned to see where to run, I saw that there was a guard with a rifle with them and he had it pointed at my belly.

That was the end of the war for me.

A gunner reported that we were last seen over Holland. We never saw Holland. We bailed out near Hanover, Germany at the village of Ourtzen. On previous raids to Berlin, the 8th Air Force flew from England directly east to Berlin. On March 22nd, we flew northeast and entered the Baltic Sea. Flying over the Baltic we entered Germany on the north shore. Because the gunner was not present at the pre-flight briefing and because we aborted the mission as we entered land, he must have thought the first land we saw was Holland. This mistake was repeated in the news reports.

Do I believe the pilot caused the malfunction of the propeller and intended to desert to Sweden? I did then, and I do now. Were the two unidentified planes approaching from behind our escort back to England? I’ve always wondered. If our pilot had followed procedure and checked each member of the crew (one or two minutes) could we have saved the bombardier? No one will ever know. [In MACR #3555, one of the waist gunners stated that there were some extra chutes in the waist that would have worked on the bombardier’s harness. As no one was informed of the bombardier’s plight, the chutes lay in the waist unused.]

1Lt Leonard W. Blednick – Crew 72 Bombardier

In his questionnaire after the war, Dave Schulz explained the reason that Lennie Blednick did not bail out: “He lost his head and I could not persuade him to jump…. Lt. Blednick could not put his chest-type parachute on because it was the wrong kind for his harness. He yelled at me to help him. I managed to fasten one side of his chute and told him to jump, but by this time he had given up hope and I could not persuade him to bail out. When the plane was below 1000 feet I had to leave him to save my own life. He was still in the nose compartment of the plane when it crashed and burned, as far as I know.

“The plane crashed about 300 yards out from the railroad station of Ourtzen, Germany. The station master or any of the town officials at the time should be able to tell where his body was buried. Ourtzen, Germany is somewhere near Hanover, Germany.”

————————-

Sgt Edward Storm, Flight Engineer, answered the same questionnaire: “He was last seen in the nose of the plane by the navigator. He had rings on his chute and rings on his harness and you can’t fasten them. He should have had snaps on the chute. We had an extra chute in the waist of the ship, but didn’t know of his trouble and all bailed out in the rear of the ship. He and the navigator were the only ones to know of his trouble.”

Photo: Blednick Family

B-24H-10-DT 41-28678 J3 M #678

Ship #678 landing after an earlier March 1944 mission

The Stars & Stripes Thursday, March 23, 1944

2Lt Samuel D. Scorza wrote his family about the loss of his friends

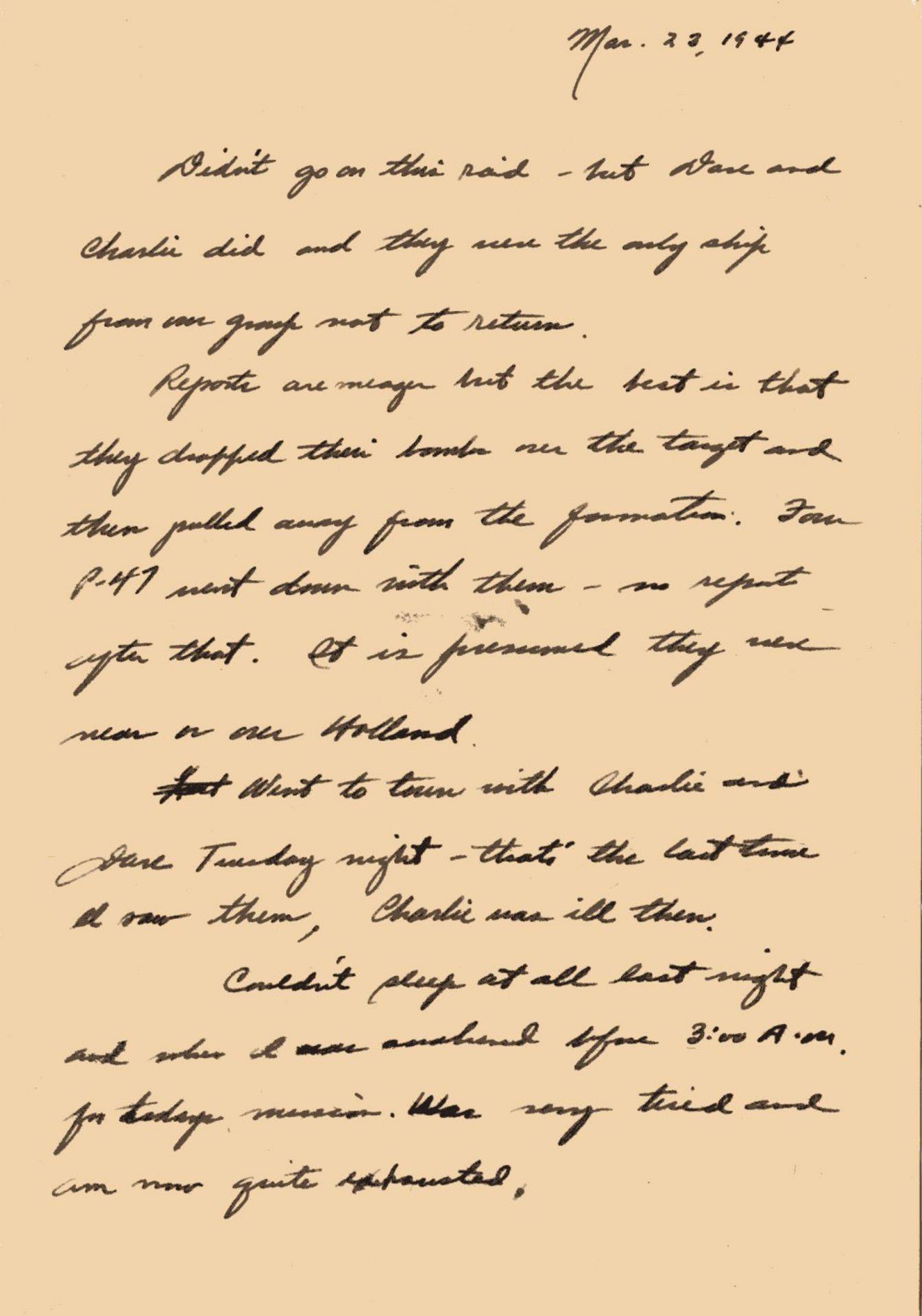

March 23, 1944

“Didn’t go on this raid – but Dave and Charlie did and they were the only ship from our group not to return. Reports are meager but the best is that they dropped their bombs over the target and then pulled away from the formation. Four P-47 went down with them – no report after that. It is presumed they were near or over Holland. Went to town with Charlie and Dave Tuesday night – that’s the last time I saw them, Charlie was ill then. Couldn’t sleep at all last night and when I was awakened before 3:00 A.M. for today’s mission was very tired and am now quite exhausted.”

[I recall my father telling me of his best friends, “Dave and Charlie” being shot down during the war. I had always assumed that they had been killed. It was not until after my father had passed away that I came into contact with Dave Schulz and learned what had happened to them on the day they went down. I believe my father never knew that they ended up as prisoner’s of war, and had also assumed that they had all been killed.]

First Air Medals

Recipients of the group’s first Air Medals – Sgt’s Dugmore and Pilkington; Lt James W. Davies (Crew 71)

(Photo: FOLD3.com)

Sgt Donald Dugmore Memories of Stalag Luft I

A few years ago my son sat with my father and listened to many stories. He documented their talks. One of the paragraphs on your website says it is unclear how the enlisted men went to the officers camp at Stalag Luft I. This may shed some light.

The next thing he told me about was he and the other men captured in the area were loaded into filthy boxcars to be transported by train to prison camp in what he believed was Poland. He said all that he knew was that it was colder than hell and they had them jammed in the cars like a bunch of animals. When they arrived at the camp they were intended to stay, there was nowhere to put all of the prisoners. The camp’s barracks were completely full. The Germans asked if there were any volunteers to take a three day train ride back to Stalag Luft I. The last thing that any of the men wanted to do was get back in the car because of the cold, but grandpa knew that Stalag Luft was an officer’s prison camp so he encouraged six other men in his flight crew to go back with him. They agreed and re-boarded the train.

When they arrived he was put into a bunk room with fourteen men. He said the room was roughly the size of his living room which I would guess to be about 10 by 20. He was assigned to kitchen detail where he was initially in charge of washing the bowls that the prisoners ate out of. Every meal they ate at the camp was served in bowls no matter what it was. He remembers a good bit of the food being a daily bread ration and things such as potatoes. He said that an open cart would be brought into the camp and the contents would literally be dumped out onto the ground. The men on food detail would be responsible for going out to gather it before it froze or spoiled if it wasn’t already. The food was never packaged in anything it was just piled into the cart so things such as bread would be in the open air and most likely be stale by the time they ate it. He said the loafs of bread would be cut into equal pieces and it would be first come first serve for the best pieces. He said if you got there first you could get a center part of the loaf and if you were last you would get the heal which would surely be stale. There were not enough bowls for all of the men in the camp to be served at once so they would be served in shifts.

Grandpa just threw this number out there but he said they would do about 400 bowls for each shift which there would be about three. He was later offered the opportunity to “advance” to the kitchen position of pan scraper where he wouldn’t be responsible for washing the pans, but he would get the crusty stuff out of the corners and off of the sides. He told me one of the meals he could remember was a casserole made of spam and graham crackers. The longest he remembers going without food was about three days. He said one day wasn’t bad, two days was alright, but after three days he remembers being pretty damn hungry. They never knew if they would get fed on any given day. He said they would get supplies sent to them from the red cross and higher ranking officers in charge of them would save them up until it was enough to make a meal for the men.

(Courtesy Gail Dugmore Crispin)

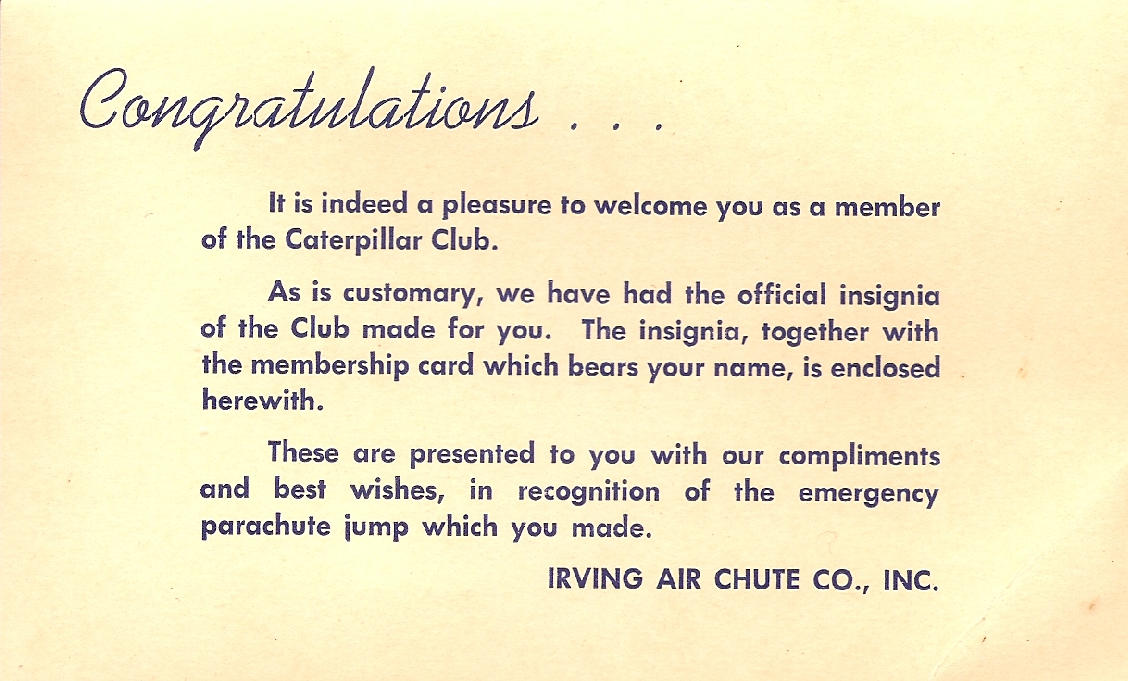

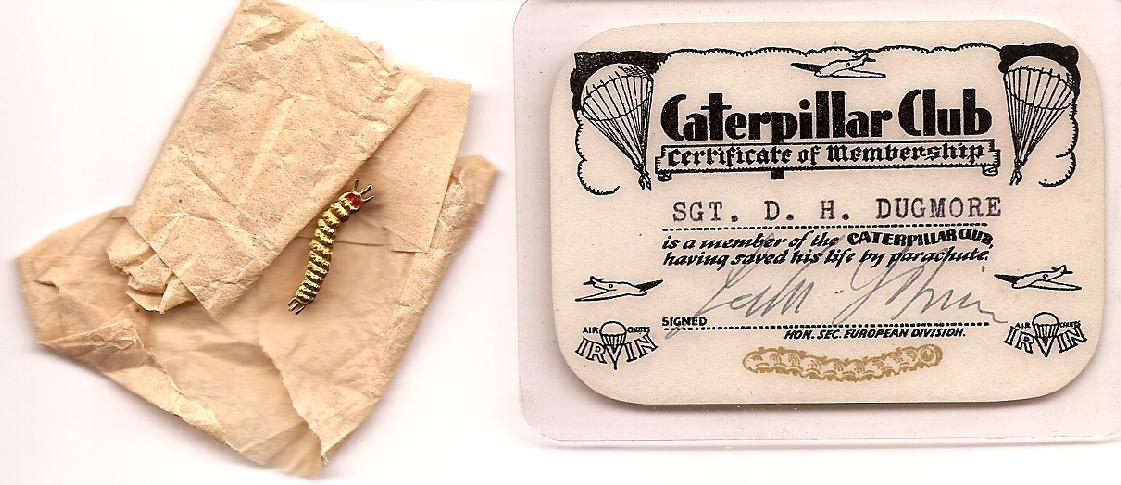

Donald Dugmore’s Caterpillar Club certificate and pin.