Crew 71 – Assigned 755th Squadron – October 21, 1943

(Photo: Gary DeForest)

Shot down April 9, 1944, Easter Sunday – MACR 3837

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Pos | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2Lt | Joseph M Stroup | 0745849 | Pilot | 09-Apr-44 | KIA | Ardennes American Cemetery |

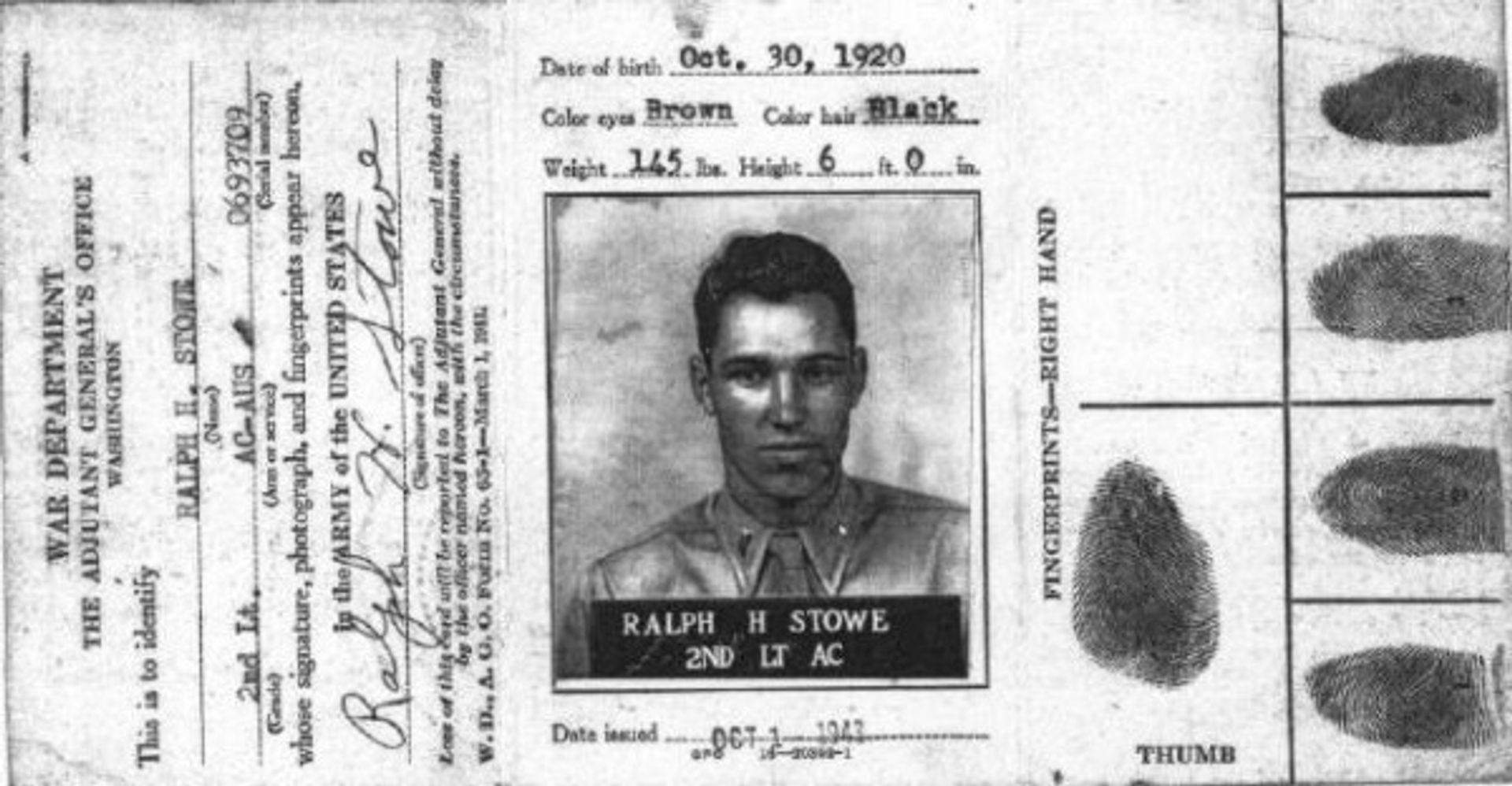

| 2Lt | Ralph H Stowe | 0693709 | Co-pilot | 09-Apr-44 | POW | Stalag Luft I |

| 2Lt | James W Davies | 0809329 | Navigator | 09-Apr-44 | POW | Stalag Luft I |

| 2Lt | Michael Boury, Jr | 0752835 | Bombardier | 09-Apr-44 | POW | Stalag Luft III |

| T/Sgt | Earl W Fortune | 39167857 | Radio Operator | 09-Apr-44 | POW | Stalag 17B |

| S/Sgt | Russell G Grower | 19179944 | Top Turret Gunner | 09-Apr-44 | POW | Stalag 17B |

| Sgt | Harold H DeForest | 31277495 | Ball Turret Gunner, 2/E | 09-Apr-44 | POW | Stalag 17B |

| Sgt | Edward G Hovey | 14137888 | Airplane Armorer | 08-Aug-44 | UNK | Reld attachment 60SC |

| S/Sgt | Paul B Parkinson | 19176130 | Aerial Gunner, 2/E | 09-Apr-44 | POW | Stalag 17B |

| T/Sgt | Tommy Glass | 38202709 | Flight Engineer | 09-Apr-44 | KIA | Ardennes American Cemetery |

2Lt Joseph M. Stroup and his crew were assigned to the 755th Squadron in October 1943 and trained with the group at Tonopah prior to movement overseas in January 1944. While their names do not appear on available movement orders, it is most likely that they flew a B-24 along the Southern Route like the rest of the group.

Lt Walter Kulig may have been removed from the crew during training. He is not shown on any 458th records. Lt James W. Davies, assigned to the 755th Squadron from the 399BG at March Field, joined the crew on December 29, 1943, just prior to the 458th leaving for the ETO. Sgt Edward J. Hovey apparently made the trip to England the crew, but did not fly any missions with them and was most likely removed from combat flying. His name appears on group records only once, in August 1944 where his MOS is listed as 911 (Airplane Armorer). It was due to this vacancy on the crew that saw them assigned several fill-in gunners on their March and April missions. The last of these, S/Sgt Kenneth F. Duffy, a gunner on Lt Rex Brudos’ crew, had the misfortune to be the replacement on the April 9th mission to Tutow, Germany.

The crew flew on the second February diversion mission to the Dutch Coast and also participated in the group’s first credited combat mission on March 2nd. Missions to Bordeaux in southern France, Berlin and Friedrichshafen in Germany followed; and the raid on the 26th to Bonnieres, France rounded out the month of March with the crew completing five missions.

After two additional missions at the beginning of April, the crew was slated to fly to Tutow, Germany on April 9th (Easter Sunday) to bomb the airfield there. The group came in over the North Sea and crossed the enemy coast south of Flensburg, Germany and continued east to pass just north of Kiel. The weather had hampered the entire 2nd Bombardment Division on this day and was the cause of several bomb groups turning back. At 1110 hours, when the 458th broke out of the clouds over Kiel Bay, the Luftwaffe was waiting in force. Reports indicate that 35-50 German ME-109’s and FW-190’s were waiting, and that the 458th was attacked by 7-10 of these.

Three 458th Liberators were damaged to the extent that they were forced out of formation. Lt Byron Logie turned north towards Sweden, as did Lt Walter Mangerich and his crew from the 752nd Squadron. Lt Walter Raiter, 754th Squadron, with number 4 engine on fire was last seen heading NNE in the vicinity of Gedser Head, Denmark. All of these aircraft were last seen with enemy fighters following them, and under control. None of these aircraft would return to Horsham.

Whether or not Lt Stroup’s aircraft was damaged or knocked out of formation in this first wave of attacks is not clear. Lt Boury, the crew’s bombardier, mentions in his statement after the war that they dropped their bombs on the target at 1330 hours just before they were hit by fighters. It is possible that over time his memory had become clouded since his recollection of the target being Osnabruck is incorrect, and it is more than 300 miles away from Tutow. However, the town of Lingen, where all of the surviving crew state that the bodies of Lt Stroup and Sgt Glass were taken, is just 52 miles from Osnabruck.

According to the Missing Air Crew Report the aircraft crashed, “At Soegel, district of Aschendorf-Huemling…at about 1500 hours.“

Lt George Schuman, pilot in the 753rd Squadron, told the debriefing officer the following

“An A/C believed to be Stroup’s was hit by E/A over Kiel Bay and was forced to leave the formation. Four (4) ME-109’s were seen following A/C, but not attacking it. A/C was last seen over Laaland heading in direction of Sweden under control.”

However events transpired, Lt Stroup and crew, as is evidenced by the crew statements below, would not make it back to Horsham either.

Crew 71 Enlisted Men – Tonopah, Nevada 1943

(Photo: Gary DeForest)

Missions

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25-Feb-44 | DUTCH COAST | D2 | -- | 42-52441 | -- | J3 | D2 | LAST CARD LOUIE | Diversion Mission |

| 02-Mar-44 | FRANKFURT | 1 | 1 | 42-52423 | R | J3 | 1 | UNKNOWN 031 | |

| 05-Mar-44 | BORDEAUX/MERIGNAC | 3 | 2 | 42-52423 | R | J3 | 2 | UNKNOWN 031 | |

| 08-Mar-44 | BERLIN/ERKNER | 5 | 3 | 42-52423 | R | J3 | 3 | UNKNOWN 031 | |

| 16-Mar-44 | FRIEDRICHSHAFEN | 8 | 4 | 41-29342 | S | J3 | 4 | ROUGH RIDERS | |

| 26-Mar-44 | BONNIERES | 14 | 5 | 42-52423 | R | J3 | 5 | UNKNOWN 031 | |

| 05-Apr-44 | ST. POL-SIRACOURT | 16 | 6 | 42-52423 | R | J3 | 7 | UNKNOWN 031 | |

| 08-Apr-44 | BRUNSWICK/WAGGUM | 17 | 7 | 42-52423 | R | J3 | 8 | UNKNOWN 031 | |

| 09-Apr-44 | TUTOW A/F | 18 | 8 | 42-52423 | R | J3 | 9 | UNKNOWN 031 | FTR - FIGHTERS OVER KIEL |

Crew Member Statements from Missing Air Crew Report

James Davies – Navigator

Sgt Glass was on flight deck with fire extinguisher in hand. Lt Stroup was still at controls when he ordered us to bail out. The fire in the bomb bay was intense. It is believed [Lt Stroup] went out the top hatch and struck rudders on B-24. Upon our capture by the Germans on April 9, 1944, we were taken immediately to a civilian jail. We were not told the name of the village so cannot give any definite information in that respect. However, the next day we were loaded into a German military truck, which contained all of our paraphernalia – parachutes, escape kits, etc. In this truck there were three coffins. One was evidently that of a German as it was draped with the Nazi flag. The other two were wooden affairs upon which were written the names of our two crew members – Joseph Stroup and Tommie [sic] Glass. We were taken to the town of Lingen at which place the bombardier was removed to a German hospital and the two coffins were placed in what seemed to me to be the equivalent of an undertaker’s parlor in our country. The remaining seven of the crew went on to Frankfurt.

Russell Grower – Tail Turret Gunner

Three ME-109’s came in at six o’clock. I called over my inter-phone saying three times, “Enemy fighters six o’clock!” Then I started firing at the one in the middle. I saw smoke pouring out of his engine then all of a sudden I saw him burst into a mass of flames and explode. Then a second later, I was blown out of the tail turret by direct hits of 20MM from other two fighters. I looked up and saw my left waist gunner grab his knee – my hands were bleeding and I reached for my ‘chute [and the] bomb bay was on fire. I pulled my ‘chute handle by mistake and the ‘chute spilled over in back of the camera hatch. I helped open hatch, scraped ‘chute together in my arms, said a prayer and jumped. ME-109’s tried to dive on me and spill my ‘chute, but P-47’s went after them. I saw three more ‘chutes come out of our ship which proved to be ball gunner, left waist gunner, and radio operator.

From what the radio operator told me, Sgt Glass was in the bomb bay trying to put out the fire. He got gasoline on him from the gas tubes and when he bailed out thru the bomb bay which was on fire, he caught fire and burned to death on the way down in chute. Radio operator saw Tommy on ground with burnt clothes laying alongside the body which still had long underwear on. Chute was open, but burnt.

[Lt Stroup] I called back to pilot telling him I had cut my ammo in half – heard, “Okay.” from him. Navigator told me he saw him grab his legs in cockpit. The next morning after being captured, the Germans led us to a truck. Inside was two plain wooden boxes which were told to us contained our pilot and engineer. We told the Germans that Tommy Glass was our tail gunner. This was due to the fact that on top of our pilot’s and engineer’s casket was another which contained the German pilot which I shot down and I was the crew’s tail gunner.

If my pilot went down with the ship, wouldn’t it be hard to find his body? If he bailed out why didn’t his chute open? We carried him and the engineer to a mortuary in a little town named Lingen, Germany where we left them. Did not open caskets.

Earle Fortune – Radio Operator

[Last saw] Lt. Stroup (pilot) at controls – condition unknown, but believe he was wounded, I think he was hit by shrapnel. I was trying to open bomb bay doors, but he told me to leave by the top hatch. Lt. Davies said he saw him grab his legs as he (Davies) bailed out the nose wheel door. Lt. Boury said he was sure that Lt. Stroup had went out the top hatch.

[Last saw] T/Sgt Tommy Glass – on ground, dead from burns of fuel fire. We had a fuel fire in the bomb bay, and I think he finally opened the doors and bailed out, and was soaked with fuel as he did so, as he was burned bad when I saw his body on the ground. [He] may have been alive when I first saw him. I think he tried to lift his head and I called to the Germans guarding me for a doctor, and they laughed. I then felt for a pulse, but found none in wrist or throat. I am sure that both bodies are in Lingen, Germany at the Catholic Cemetery.

Michael Boury, Jr – Bombardier

Soon after dropping our bombs on the target, at about 1330 hours near Osnabruck, we were attacked by German fighters. The ship burst into flames in the bomb bay. The assistant engineer and navigator bailed out the nose wheel hatch. The tail gunner, waist gunner, and ball turret gunner left from the waist window. I lifted the radio operator and co-pilot through the top hatch on the flight deck. Being last in the ship, my only exit was through the burning bomb bay. I suffered third degree burns on my face.

I last saw T/Sgt Tommy Glass, engineer, going through the burning bomb bay from the flight deck. I believe Sgt Glass was burned badly in exit and I don’t think he ever used his chute. This is based on fact of comparison since I left ship by same exit, I received 3rd degree burns and chute on fire. I put chute out by taking a free fall. I last saw Lt Joseph Martin Stroup, pilot, on the flight deck. He and I were last in the ship. I lifted him through the top hatch as I did the radio operator and co-pilot who both landed safe, in preference to exit by the flaming bomb bay. I used the latter exit myself as there was no one to lift me out the top hatch.

My wife and I made a special trip to North Carolina to see Lt. Stroup’s parents (next of kin). We, Lt. Stroup and I, had agreed on this in case the misfortune should overtake one of us. I am telling you this so you will know the story I told them. I assume he hit the rudder on exit from the ship.

I swore to the parents that his chute opened. This is an assumption. For fact, I located the area by map in which he was buried within a few miles. A French chaplain, also a POW as I, read a sermon at his and Sgt Glass’ burial. The chaplain claims to have placed flowers on the grave. (Chaplain’s name unknown). They were buried in wood boxes substituted for caskets. They were buried separately and as well as possible under the circumstance according to the French chaplain.

I met the chaplain at a POW hospital in Lingen, Germany where I partially recovered from burns received on exit from the ship before being sent to Stalag Luft III, Sagan, Germany.

This Casualty Questionnaire finally caught up with me at Valley Forge General Hospital in Phoenixville, PA. at which time I was recovering from an eye operation resulting from burns received when shot down. This is to explain the delay in returning this questionnaire.

Harold Deforest – Nose Turret Gunner

Bomb bay was on fire, and T/Sgt Glass went out thru the flames. I believe that his chute was damaged by the fire and would not open, because the other man who went out the bomb bay was burned. I saw a casket the next day which the Germans said contained the body of a man from our plane. There was no name or serial number on the casket, but Glass was the only man from our plane not accounted for.

Lt Stroup jumped out the top hatch. Bombardier thinks that he hit the vertical fin and never opened his chute. Next day, eight of us who had bailed out safely were transported in a truck to a prison camp. A casket with Stroup’s name and serial number marked on it was thrown into the truck with us.

2Lt Ralph H. Stowe ID Card

S/Sgt Kenneth F. Duffy

Sgt Duffy was a fill-in with Stroup’s crew on April 9, 1944. He was assigned with Lt Rex Brudos’ crew.

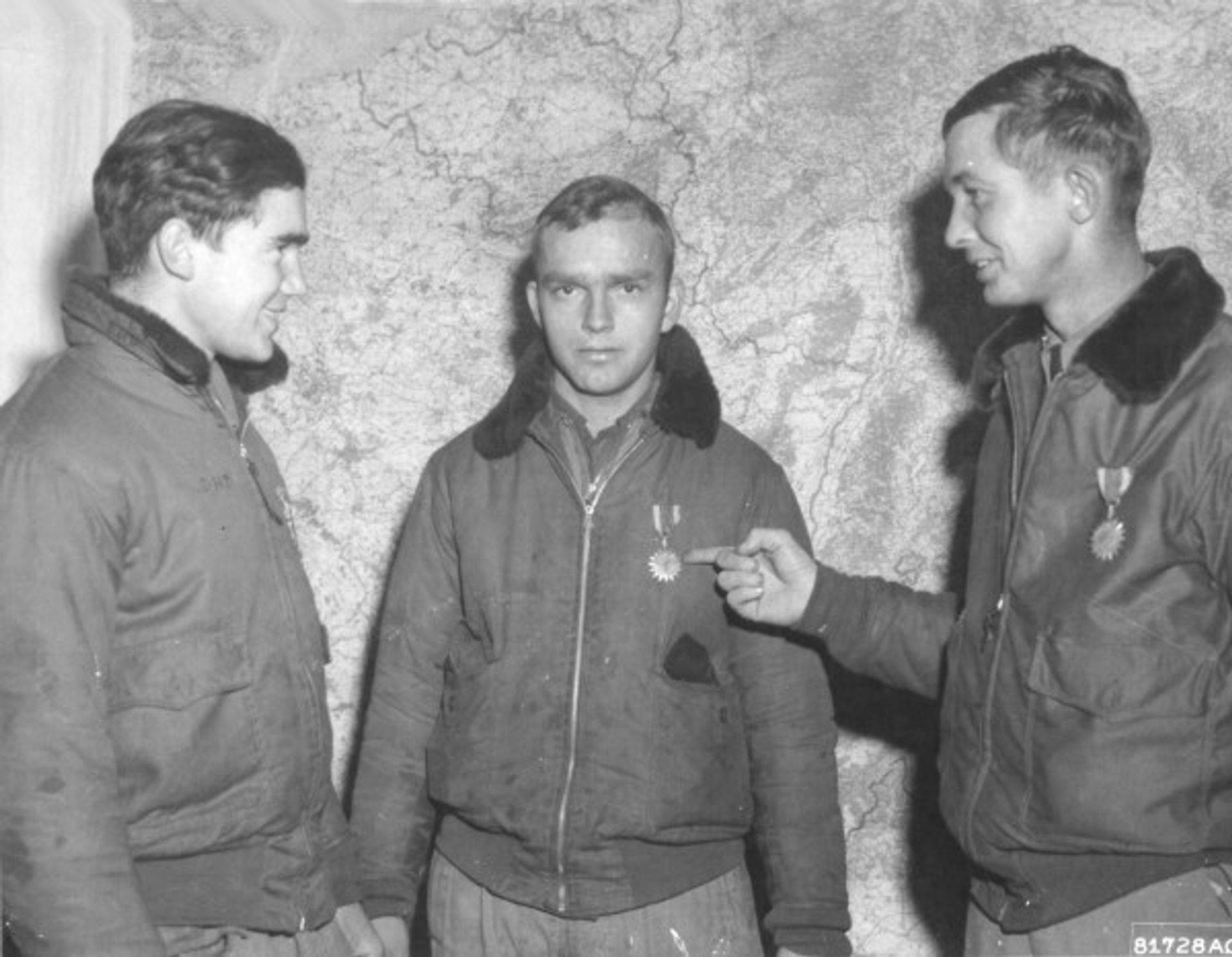

First Air Medals

Recipients of the group’s first Air Medals (L-R): Sgt’s Donald Dugmore, Dean Pilkington (Crew 72), and Lt Davies.

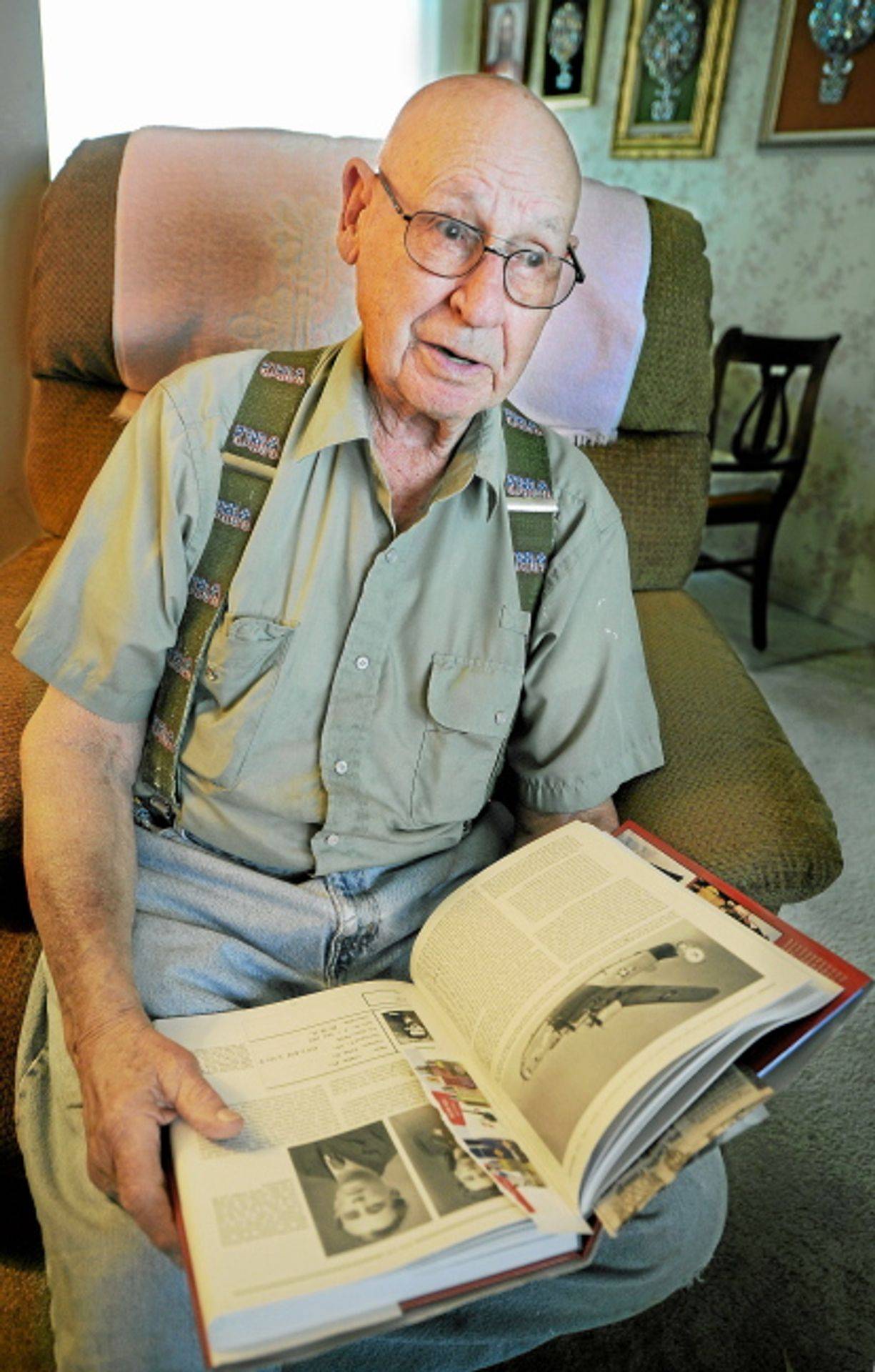

Alhambra WWII veteran revisits his prison in Austria to seek closure

ALHAMBRA – Imprisoned by the Nazis in Stalag 17-B near Krems, Austria, for 13 months, Paul Parkinson never thought he’d want to see those barracks again.

Parkinson, now an 89-year-old Alhambra resident, completed eight missions as a flight maintenance gunner and staff sergeant aboard a B-24 Liberator. His ninth mission ended in disaster. The bomber was shot down on Easter Sunday 1944 1944, and the crew bailed out over enemy territory.

The survivors were taken prisoner and hauled into a prison camp where they remained until the spring of 1945. Nearly seven decades later, Parkinson has returned to Europe this week for the first time since he left as a free man who weighed just 110 pounds.

“I’ve always wanted to go back and make some kind of contact with the (past),” Parkinson said. “At least it would take a little of the burden off my shoulders. You carry that burden for all these years.”

The mission

Sixty-nine Easters ago, it all started with a mission. Three Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter planes overwhelmed Parkinson’s crew as they tried to bomb a ball-bearing factory in Germany. American gunners shot down one plane, but the machine-gun fire from the remaining two caused his Liberator to catch on fire, Parkinson said. “We were not going to be able to make it back to England,” Parkinson said, recalling a barrage of anti-aircraft fire and German fighters hot on his tail. “We lost two crew members while bailing out. The pilot hit the rudder and an engineer gunner went through the flame. Everything burned off of him except the parachute.”

The remaining eight crew members landed in the German countryside. An elderly farmer took the eight survivors into custody. The POWs were sent to Frankfurt, Germany, for interrogation and then dropped off at Stalag 17-B. Enclosed in two rows of barbed-wire fencing, the prison camp housed Allied airmen including Americans, French, Italians, British and Russians. Like many young men of his generation, Parkinson witnessed horrors that became forever entrenched in his memory. One incident in particular haunts him to this day, and it’s his reason for wanting to return.

Return trip

Parkinson has returned to Europe and tour Berlin, Munich, Salzburg and Vienna with Ray and Kathy Bence, both 59. Parkinson, who left Saturday and will return on June 5, [2013] wouldn’t have been able to go if not for the Bence’s. The friends from church donated their frequent-flier miles and promised to pay for most of his expenses. “I never served in the military,” Ray Bence said. “They were called the Great Generation: That’s my father’s generation. We feel privileged to be able to do this (because) that generation is heading out. Parkinson said he’s delighted because the only time he has ever toured Berlin – or any of Europe for that matter – was during World War II, when he was too busy bombing, shooting and trying to stay alive to enjoy beautiful vistas or landmarks.

Life in the barracks

American POWs, unlike their abused and much more malnourished Russian counterparts, lived relatively comfortably because of the 1929 Geneva Conventions, which dictated that war victims be protected and treated humanely. The Soviet Union didn’t sign the agreement.

“It was a very dreary place. There wasn’t much to do,” Parkinson said, though the POWs could play volleyball, basketball, baseball or football.

Things were swell when Red Cross parcels came. That was when the American POWs feasted on Spam, chocolate bars, sugar cubes, dried milk and sometimes even fish, he said. But other times, they had only hot water

“For about three months we had dehydrated vegetable soup,” Parkinson said. “Twenty to 80 percent of it was worms. As long as the worms weren’t waving at us, we ate them.” Yet the guards didn’t mistreat the prisoners, Parkinson said. There was tension, but the Germans didn’t want to cause a squabble. If that happened, they might be taken to the Russian front. “They knew how cruel the Russians were because they were cruel to the Russians,” he said. And one day, one German guard realized he had also mistreated the Americans.

The journey

That guard took leave to visit his wife and 6-month-old son, who was about to be taken away to a nursery run by Nazis. On the way to see them, the guard’s passenger train stopped right beneath American P-51s, which circled them. Dodging German flak, the U.S. fighters waited until the civilians escaped safely before they fired their .50-caliber guns, Parkinson said. When the guard returned to camp, he shared his story with the POWs. He began bawling and said he would probably be dead if the Americans had shot at his passenger train.

“They (the Germans) were taught that we were women- and baby-killers,” Parkinson said. The guard apologized to the internees, “saying that ‘it was all a lie’ and ‘it was all propaganda,'” Parkinson said.

As the Russians pushed west toward Germany, they sought revenge because of the Nazis’ brutal treatment, reported America in WWII magazine. The German guards at Stalag 17-B corralled able-bodied POWs and started marching along the Danube River through the Black Forest, Parkinson said.

“On the march, not one of the Russian prisoners finished,” he said. “Some committed suicide. Others died on the way.”

As for Parkinson, he caught dysentery on the third day. That same day, Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army caught up with the group and took the German guards into custody. The commanding sergeant asked if any of the POWs had a grudge against their German captors, and one man fingered the remorseful guard. “The sergeant then rested his rifle against a tree and turned his back, saying ‘I will not look’ and to ‘take him down to the gully’ and ‘to take care of him,'” Parkinson said.

The man had just given orders for the vindictive murder of a man with a 6-month-old son and a wife. Nonetheless, if anyone had a problem with his order, that individual would be “taken down,” too, Parkinson recalled the sergeant saying. “I would’ve liked to have said something, but I was down to about 110 pounds at the time, and I just turned around and walked away,” said Parkinson, who is 5 feet 10 inches. “There was nothing that I could do. The war was basically over. We knew it and the Germans knew it, so it didn’t make sense why things like this could happen.”

Parkinson, now bald and bespectacled, grew quiet as he sat in a brown recliner in his apartment. His Army green suspenders had a smattering of American flags in the shape of the words “USA.” “It’s always bothered me that this guard was shot,” he said. “You have to learn to hate your enemy in order to be able to kill them. But when the war is over, it’s over. You should just drop it.”Parkinson said he hopes to find the guard’s son.

Parkinson’s daughter, Linda Corum, who lives in West Hills, said she initially had “mixed emotions” about her father’s travel plans because he has had a couple of small strokes and heart valve-replacement surgery; he lives with a pacemaker. “I think it’s a good idea for him to get closure on this, but I also worry. He’s 89 years old. He has a cane. He has had heart problems in the past. I worry that it’ll be too much for him.” Parkinson, however, is determined to go. “Well, if I die, I die,” Parkinson said. I’ll know that “I tried to do everything I could to help a (German guard’s) son have closure.”

The hitch

Parkinson has never met this son. And he doesn’t remember the dead guard’s name. But he said he would recognize the guard’s name if he saw it when he visits Stalag 17-B. He doesn’t realize that his former prison camp is now an airport for sport fliers. Some monuments outside that area remind visitors of what once was there, and rusty steel plates with the word “remember” are inscribed in the 12 languages of the people who lived or were imprisoned there, according to a German website called Next Room. Parkinson’s stories will be added to a Wall of Fame that will be built next to one of the airport towers around the town of Gneixendorf, organizer Christine Wolfel said. Her father’s visit is a long shot, Corum admits, but she holds out hope that her father will also find closure. “He doesn’t even remember the guy’s name. That’s going to be hard to get the son,” she said. “The son might not be alive anymore because he’s about 68. But there might be a son out there that recognizes stories that his mother told him.”

Either way, Parkinson isn’t worried. “Whether I can contact the son or not is maybe not as important as just making the effort of doing it,” he said

Read more: Pasadena Star News

Russell G. Grower

After being shot down and captured, Russell Grower spent almost 13 months in Stalag 17b. In 1945, while being forced to march to another camp, he collapsed on the road. Many other prisoners had died on the same march, and were buried by the roadside by other prisoners. Although unconscious, Grower was not dead. His fellow prisoners buried him, but covered him with leaves instead of dirt, undetected by their German captors.

A few days later, Grower regained consciousness, and made his way to a farmhouse, where a woman hid him and nursed him back to health. He later found and joined a group of French escaped POWs, and the group fought their way to Allied lines. Grower returned to the USA and eventually joined the Ontario (California) Police Department on October 19, 1951.

On Friday February 2, 1958, Detective Russell G. Grower and two outside agency Detectives were investigating a tip on a gang of tire thieves. At 1415 hours, Detective Grower knocked on the front door of a Soquel Canyon house and was met by Lester Bonds. Grower identified himself to Bonds as an Ontario Police Detective. Bonds said, “I got no time for Cops” and started to shut the door. As Grower advanced and attempted to communicate with Bonds, he was shot in the forehead.

Grower was rushed to the hospital, but was pronounced dead on arrival. Bonds fled the scene but was later apprehended and charged for the murder of Detective Grower.

Detective Russell Grower paid the ultimate price for his City and Fellow Man. Grower was survived by his wife Mary and children David, Sandra and Robin.

Grower was recognized for his wartime service and POW experiences, and was courted by Hollywood for his story and expertise. He appeared as a POW in the famous 1953 film Stalag 17.

He is listed as an actor in IMDB and other movie sites.

Information courtesy: Ontario Police Officers Association and Byron Lee