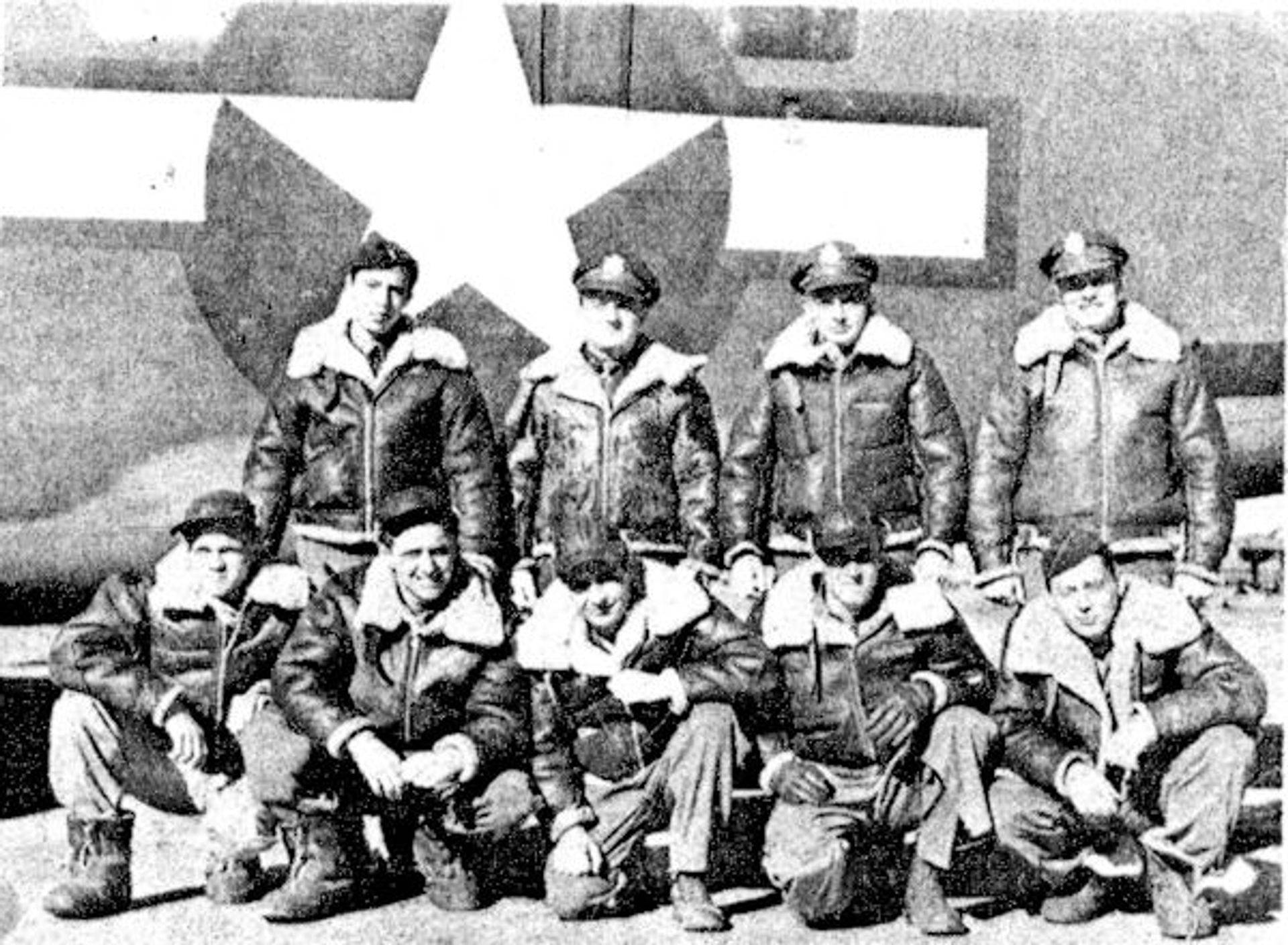

Crew 3 – Assigned 752nd Squadron – October 1943

Standing: Meron Landon – G, Paul McMillen – G, William Becker – CP, Jack Martin – P

Kneeling: Marion “Buzz” Morehead – RO, Unknown, Charles Jackson – E, Unknown

If you can identify anyone in the photo, please contact me.

(Photo: AFHRA)

Transferred to 451BG 15AF

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Pos | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1Lt | John S Martin | 0526238 | Pilot | Apr-44 | TRSF | Transferred to 451BG 15AF |

| 2Lt | Willard B Becker | 0811314 | Co-pilot | Apr-44 | TRSF | Transferred to 451BG 15AF |

| 2Lt | Robert J Wohl | 0812029 | Navigator | Apr-44 | TRSF | Transferred to 451BG 15AF |

| 2Lt | Eugene Nosarzewski | 0688389 | Bombardier | 19-Jul-44 | UNK | Air Crew Leave |

| T/Sgt | Marion M Morehead | 16160267 | Radio Operator | Apr-44 | TRSF | Transferred to 451BG 15AF |

| T/Sgt | Charles E Jackson | 35303347 | Flight Engineer | Apr-44 | TRSF | Transferred to 451BG 15AF |

| S/Sgt | Robert B Martin | 18084806 | Aerial Gunner/2E | Apr-44 | TRSF | Transferred to 451BG 15AF |

| Sgt | Meron L Landon | 18119908 | Aerial Gunner/2E | Apr-44 | TRSF | Transferred to 451BG 15AF |

| S/Sgt | Andrew D McGowen | 34256556 | Armorer-Gunner | Apr-44 | TRSF | Transferred to 451BG 15AF |

| Sgt | Paul L McMillen | 39692601 | Armorer-Gunner | Apr-44 | TRSF | Transferred to 451BG 15AF |

Crew 3, under 1Lt Jonathan Martin, trained with the 458th in Tonopah, Nevada in late 1943, and moved the England with the group in January 1944. Assigned with the crew early on was co-pilot, F/O Kenneth A. Brett and gunner S/Sgt Arthur R. Hendrickson. These two names appear with the rest of Crew 3 on a set of movement orders dated October 5, 1943 when the group moved by train from Gowen Field to Wendover. At some point during training at Tonopah, Brett was moved to the crew of F/O Harold W. Hetzler; and Hendrickson went to the crew of 2Lt Calvin G. Cragun. Their places were filled by 2Lt William B. Becker as co-pilot, and S/Sgt Andrew D. McGowan as gunner. Becker had been the co-pilot on Hetzler’s crew. This crew, including Brett were all Killed in Action on March 23, 1944 when their aircraft suffered a direct flak hit in the bomb bay, just before the target. McGowan came from the crew of 2Lt Sigmund B. Hons, who had crashed during training, killing eight of the nine men aboard. McGowan did not make that flight as he was ill.

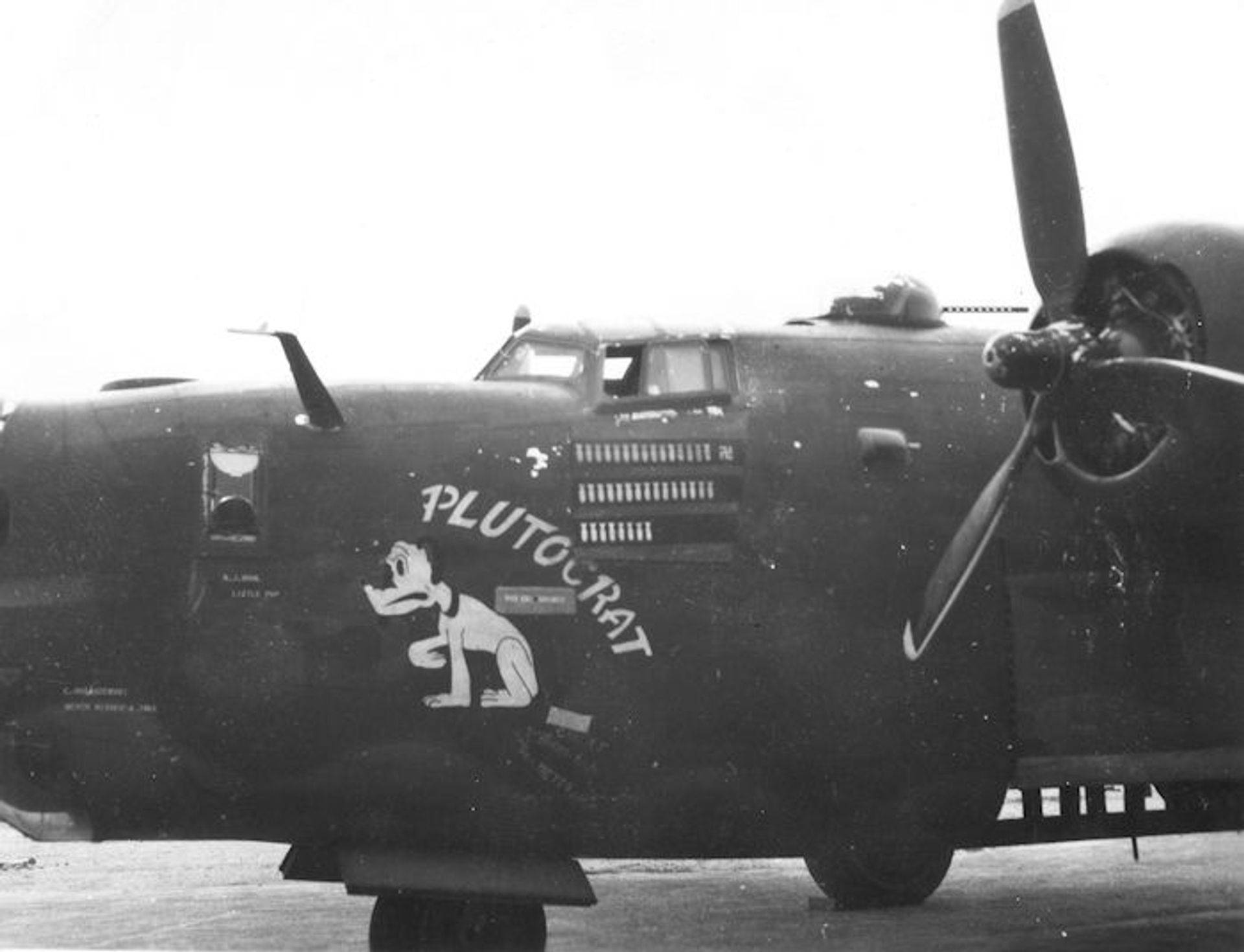

Their time with the group in England was short, but in the month of March 1944, they flew eight missions including one aborted effort on March 3rd. Most of their missions were flown in B-24H-15-FO 42-52455 7V O Plutocrat. Their last mission was on April 8, 1944 to Brunswick, Germany. Shortly after this the entire crew, except for bombardier, 2Lt Eugene Nosarzewski, was transferred to the 451st Bomb Group in the 15th Air Force. Taking Nosarzewski’s place was 2Lt Felix Ascenio, the bombardier on the crew of 1Lt Ronald A. Gulick. The crew completed their combat tour with the 451st.

Missions with the 458th

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 03-Mar-44 | BERLIN | 2 | ABT | 41-28667 | -- | 7V | -- | JAYHAWKER | NUMEROUS MECH ISSUES |

| 06-Mar-44 | BERLIN/GENSHAGEN | 4 | 1 | 41-28709 | I | 7V | 3 | LUCKY STRIKE | |

| 09-Mar-44 | BRANDENBURG | 6 | 2 | 42-52455 | O | 7V | 1 | PLUTOCRAT | |

| 21-Mar-44 | WATTEN | 10 | 3 | 42-52455 | O | 7V | 5 | PLUTOCRAT | |

| 22-Mar-44 | BERLIN | 11 | 4 | 42-52455 | O | 7V | 6 | PLUTOCRAT | |

| 23-Mar-44 | OSNABRUCK | 12 | 5 | 42-52455 | O | 7V | 7 | PLUTOCRAT | |

| 26-Mar-44 | BONNIERES | 14 | 6 | 42-52455 | O | 7V | 8 | PLUTOCRAT | |

| 27-Mar-44 | BIARRITZ | 15 | 7 | 42-52455 | -- | 7V | 9 | PLUTOCRAT | |

| 08-Apr-44 | BRUNSWICK | 17 | 8 | 42-52455 | O | 7V | 11 | PLUTOCRAT |

A.W.O.L.

Crew #3 of the 458th Bomb Group, 752nd Squadron was one of the first B-24 Liberator bomber crews to arrive at the newly transformed Tonopah Army Air Field during November 1943. They would complete their final phase of combat training at T.A.A.F.

Former S/Sgt Paul McMillen, the crew’s tail turret gunner, still remembers the seemingly endless training flights over the Nevada desert, a preparation for the long distance bombing missions the crew would be flying over Europe [or] the Pacific.

By January 1944, Crew #3 was nearing the end of their training and knew they would be heading overseas at any time.

Sergeant McMillen, the only married man on the ten man team, wanted to see his wife and baby before being shipped out. He hadn’t been home since entering the service. He requested a three day pass from his commanding officer but was turned down. The commander wanted the crew in top shape and ready to leave at a moment’s notice. Paul realized the commander was right, but still wanted to see his family.

He did, however, receive a pass into Tonopah from his pilot. Here, he got together with some of the enlisted men from his crew and explained a plan he had come up with. Giving them information on how to contact him when they got word of being shipped out, he hurried over the state line into California to see his wife and child. Within a few days, the message arrived – “Hurry back, we are leaving.”

Hitchhiking back to Tonopah, Paul turned himself in at the base’s main gate. Shaking in his boots and thinking of what might happen, he was jeeped to the squadron commander. Soon he was being raked over the coals for what he had done. The commander asked if he would like flying as a private. Paul answered, Sir, I haven’t missed any training and wouldn’t want to be on the crew as a private.”

At that point the officer sent him to the pilot of the crew for punishment. The pilot instructed him to put on a back pack parachute and begin walking the ramp. A few hours of this completed his punishment.

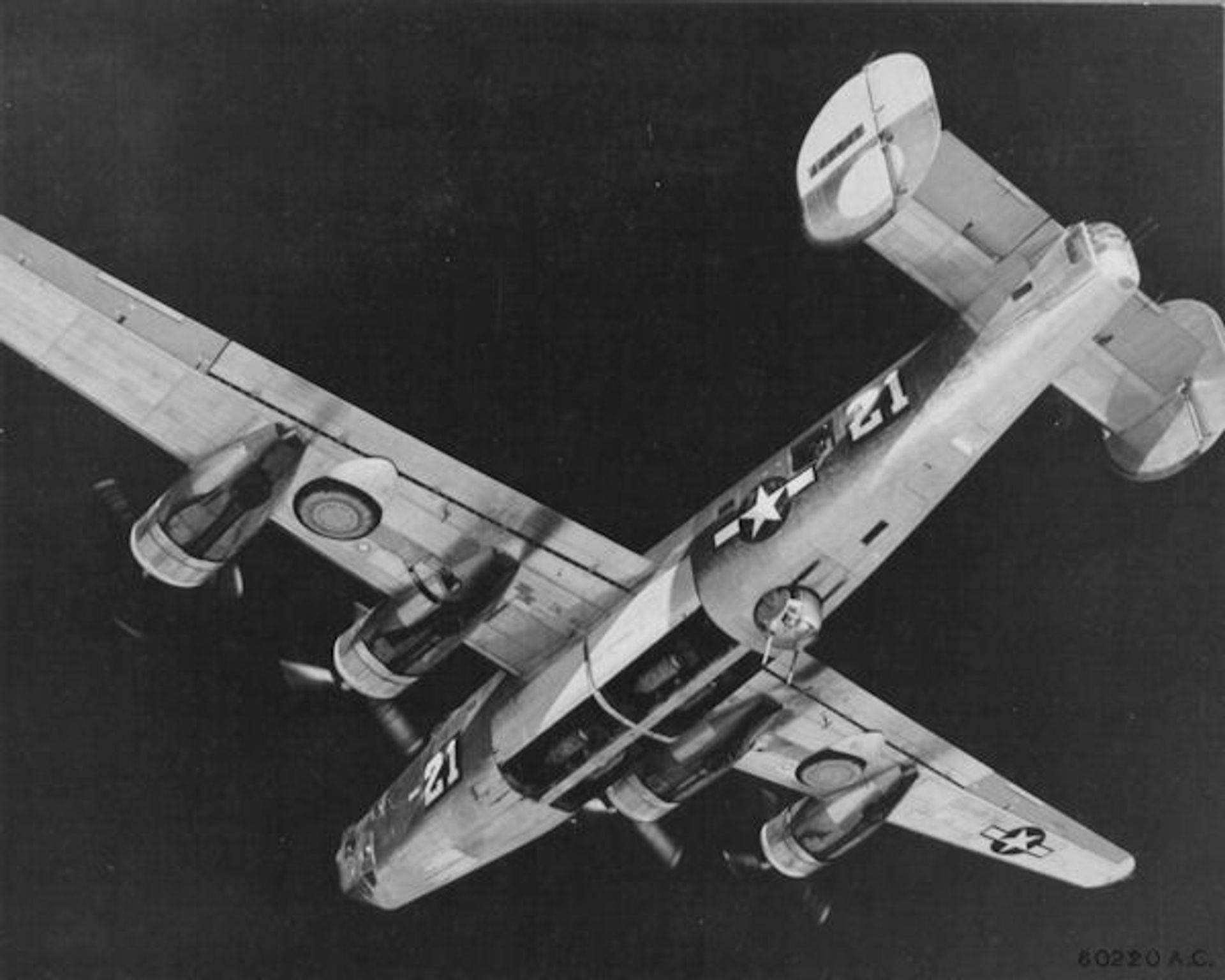

B-24H-15-FO 42-52455 7V O Plutocrat showing 38 missions and one fighter down, long after Martin and crew had departed for Italy.

Of note is the notation at the bombardier’s station: C. Nosarzewski – “Never misses a Trgt” and under the navigator’s window: R. Wohl – “Little Pup”

Two days later the 458th left T.A.A.F. Within a short time, Crew #3 was assigned a B-24 nicknamed Plutocrat and sent to England. Flying out of England, Plutocrat completed 25 missions. The crew was then shipped to Italy with the 451st Bomb Group and flew 25 additional missions [sic].

As a tail gunner, McMillen witnessed the destruction of such vital and highly fortified target sites as Ploesti, Bucharest, Budapest, Vienna, Toulon, Lyons, and Blechhammer. He was awarded the Air Medal with four bronze clusters and credited with shooting down one German ME-109 fighter.

(Editor’s note: The preceding was compiled by Allen Metscher from information supplied by Paul McMillen of Desert Hot Springs, California.)

Article appeared in: Central Nevada’s Glorious Past – Vol. 13, No. 1 (Date unknown)

May 26, 1944

JACK MARTIN (724th, PILOT) SEEKS ELUSIVE CHECK-OUT CO-PILOT

I am looking for a man who flew check out co-pilot on a mission our crew made to Lyon, France on May 26, 1944. Military organizations, such as our 451st Bomb Group, Limited, have brought many old such friends and comrades together, and I’m hoping this true story will produce the desired result of learning the whereabouts of the co-pilot. I would truly like to meet him again and thank him from the bottom of my heart for his trust and cooperation on that eventful mission so many years ago.

As I sit down to relate this exciting episode, it seems like yesterday; I can hear the roar of the engines, smell the burned oil and exhaust fumes as they blew into the cockpit along with dust and sand that the propellers were picking up from the dirt surface. The aircraft was shaking and jumping – anxious to roll. We were about to make a locked brake, short runway take off and head to clear a 25 foot strafing abutment at the end of the runway. I had told the co-pilot that this was going to be “a piece of cake”. (If so, then why this strange hard lump in the pit of my stomach, this clammy feeling to the palm of my hands, and a funny shaky feeling inside of me?)

When I looked down the runway strip and saw that big concrete wall at the end, I realized it was now or never, lest I lose my courage. I supplicated to the Lord and released the locked brakes. The events leading up to this critical situation had flashed through my mind during the time before takeoff.

Our crew (right) had trained in Tonopah, Nevada, with the 458 Bomb Group, which was a B-24 heavy Bomb Group. The group joined the 8th Air Force in England. After flying a number of missions with the 458th group, I was told that I was to be transferred to the 15th Air Force. My crew was given the privilege of staying with the group or transferring with me. They all opted to volunteer and go with me. We subsequently received orders, and in May 1944, proceeded to Bari, Italy, where the reception depot had been set up for replacement crews that would be assigned to various groups in the 15th Air Force. We drew the 451st Bomb Group, located near Foggia, Italy. Upon arrival, we were assigned to the 724th squadron. After two days of “settling in”, I was told to report to squadron headquarters for instructions about flying with the group the following day. Group regulations were such that any new or replacement crews that would be flying for the first time with the group, would have a check-riding experienced co-pilot along on the first mission (more of a proficiency test than anything else).

The next day the mission was to Lyons, France. We were told that due to the distance involved, if we required fuel after the bomb drop, we were to land at Corsica and refuel. My check-rider co-pilot joined the crew at the flight line prior to that morning take off, and off we went. We presently joined the group and headed for our destination. Very soon after joining the formation I noticed that the aircraft was drifting astern, and I had to increase my throttle settings. The group did not seemed to be increasing speed, so I called to the flight engineer and told him to check the aircraft for any wind drag. He reported back that we had one main wheel of our undercart hanging down. I immediately attempted to raise it by pulling up on the landing gear handle with no results. I then pushed the lever down and lowered all of the gear; and when this was accomplished I pulled the lever back to the “up” position, and the entire gear raised. The lowering of the entire gear caused extreme wind drag, and I had to apply more throttle in order to keep up with the group while this procedure was accomplished. I was puzzled at the time why this one wheel didn’t lock in the up position, and also when I had put the gear down, I didn’t see the “locked down” position indicator light; and when I cut the throttle momentarily, with the undercarriage in the up position, I didn’t hear the warning horn blow.

We settled down to formation flying and presently the aircraft started to lose speed; once again the flight engineer said that the faulty wheel and strut had come down. We had to go through the same procedure as before and once more had to use extra throttle to keep up during the lowering and raising of the gear. At this point, my co-pilot and I discussed the problem, and the possibility that we should abort the mission and return to the base. It was decided that we should go on with the mission as everything else mechanically was operating in good order. We continued lowering and raising the wheels, increasing the throttle setting during each procedure. We completed the bombing run with the group and headed for home. As we neared the island of Corsica, I requested a fuel reading. The flight engineer told me that we had over a thousand gallons of fuel, so I felt secure that we could continue without refueling at Corsica. From Corsica the group flew parallel to the coast about ten miles out over the water and at approximately 8,000 feet. It was about 45 minutes away from Corsica, and flying in formation, that I noticed once again we were losing air speed; but this time the group was pulling away from us very rapidly. I pushed the throttles forward and was about to reach down for the landing gear lever when the flight engineer told me, “We’re out of fuel!” I immediately realized that I had lost engines on both wings as there wasn’t any yaw to the aircraft. It was determined that we had lost power on the two outboard engines due to fuel starvation. We promptly feathered the outboard engines and headed for shore. I throttled back on the two inboard engines to conserve what was left of the fuel, and started to let down gradually keeping our air speed, hopeful that we could gain as much distance as possible.

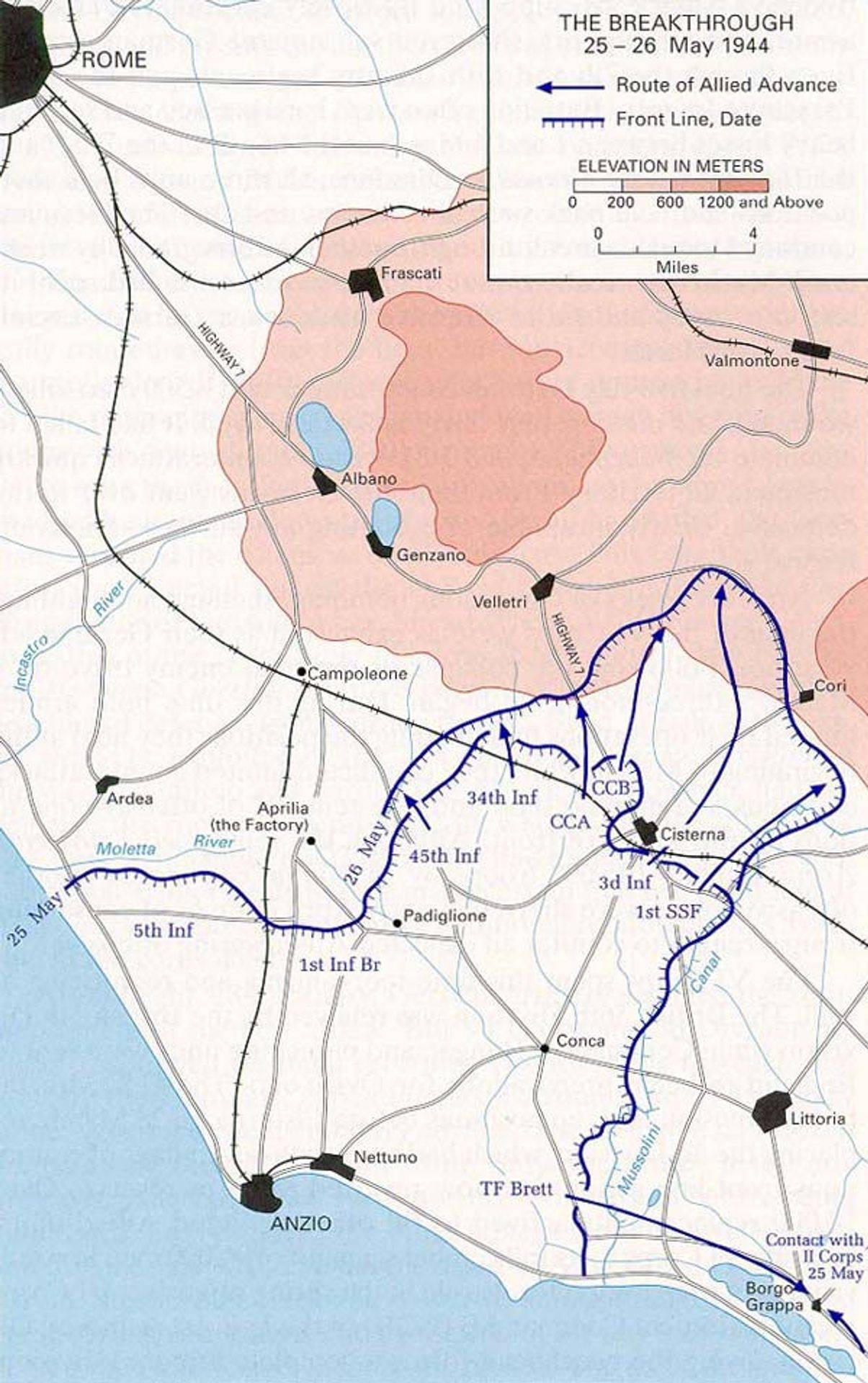

I asked the navigator, Bob Wohl, for an exact position and told the crew to prepare for possible ditching. I then told the radio operator to send the distress signal. The navigator told me we were opposite Anzio beach but couldn’t tell me if it were in Allied hands as it had been constantly contested over the past weeks. He also said that there was a short fighter plane landing strip there. I told him to come up on the flight deck and fire off the identification color code for the day with the Very Pistol. We anxiously awaited the response from the landing strip. Presently, we received their welcome answer and continued to head for shore. We had been losing altitude, and at about two or so miles from shore and at about 5,000 feet, I told the crew I was going to lower the gear, but I wasn’t at all sure whether it would lock or not, and hastened to add that they were free to bail out and assured them that those at Anzio beach would pick them up. They said they would take their chances with me. As soon as the gear was lowered, we lost altitude rapidly, but I felt that we could get lined up with the runway and still be at 1,200 feet to 1,500 feet. It turned out the landing strip was a short, temporary, perforated steel mat, Royal Air Force fighter strip with a strafing abutment at the end of the runway. On our final approach, we lost all power. The inboard engines were windmilling, and we were dropping like a stone. I put down full flaps taking advantage of the inboard windmilling #3 engine to give me hydraulic pressure. It was by the Grace of God that we touched down at the very beginning of the landing strip; the undercarriage was down and locked. I applied the brakes and somehow brought the aircraft to a stop before we ran into the strafing wall at the end of the runway.

After collecting my thoughts and aplomb, I looked over at the co-pilot; we both laughed nervously and shook hands. My legs were a bit wobbly as I got out of the aircraft and walked over to the tower shack. The landing strip was in British hands; and of course, they were in complete charge of the base and its fuel facilities. I asked about the possibility of refueling; the two pilot officers at the desk looked at one another, and one said to me with a chuckle, “Did we hear you correctly, that you wanted fuel?” I asked him to let me in on the joke. Their immediate answer was in unison, “We don’t have any to spare, chum.”

They must have taken pity on my pathetic appearance as I pled for fuel, because one of them decided to call the area commander and see what he could do. After a long conversation on the field telephone, the pilot officer turned to me and said that they could give up 500 gallons. I told him that I appreciated their generosity, but I needed much more than that if I were to reach Naples for refueling. I explained that a short field take off from a locked brake position would use up a tremendous amount of fuel; also, I might not be able to land at Naples. After more haggling, it was decided that they could let me have 800 gallons of fuel – take it or leave it. I said I would take it, and they hastened to add that we would have to load it ourselves. They didn’t say anything about the fuel being in five gallon Jerry cans, however.

While the crew loaded the fuel, I decided to pace off the runway as the British pilot officers were not quite sure whether the strip was 1,000 feet or 1,200 feet long; but they were sure of the height of the strafing abutment which they said was 25 feet high, and as firm as the Rock of Gibraltar.

I found the runway to be a little over 1,500 feet and also noted that there was a cleared field at the head of the runway which added another 300 feet of surface; but it had a lot of loose stones and turf on it, just the way the bulldozer had left it. Normally, a B-24, loaded with a full complement of fuel and bomb load, required from 5,000 feet to 6,000 feet for takeoff; without the bomb load, from 3,000 to 3,500 feet. But we had 1,800 feet and had to get over a 25 foot high strafing wall as well. I had noted a burned-out truck by the side of the runway, halfway down the strip, and I decided this would be my point of commitment. If we weren’t buoyant at that point I would cut the power and try to brake to a stop. I walked back to the crew and told them of my plans for a short field takeoff procedure and said I wanted to get as much power out of the engines as possible. The engineer said he would adjust the engine turbos for full power output and then said an odd thing, “Do you see all those GI’s sitting on ammo boxes, jeeps, trucks and so forth, alongside the runway?” I acknowledged I did. “Well,” he said, “they are taking bets on the probability of our successful take off.” I couldn’t help but ask what were the odds. He replied, “Five to one against a successful take off.” My comment was, “They’re real sports.” At this point I asked the engineer how come the fuel reading was false. He said that an airlock undoubtedly had caused the error.

I was responsible for the aircraft and knew that if I didn’t fly it off, it would undoubtedly be cannibalized for parts, or worse yet, just be demolished for scrap and bulldozed out of the way. It was a good aircraft, and the group was short of equipment, which became the deciding factor in favor of chancing the takeoff.

We had landed at approximately 1300 hours, and by now it was getting on late in the afternoon. I went over to the tower shack and asked if they could give me the identifying night color code of the day in order to make a Naples landing. They said that they didn’t have it. Could they call and get it? They said that due to security reasons they couldn’t get the code over the telephone. I said, “Well, maybe we should stay over until the following day.” They said it was chancy as the strip might fall back into enemy hands. They also said that if I wished to make a late evening takeoff, the wind would come up about 2200 hours. This was too risky at best to make a short field take off without worsening the situation by making it at night. One of the people in the tower said that I was to turn to the right sharply in a 180 degree turn after clearing the strafing wall; to turn to the left would take us directly over enemy guns that were mounted on the beach north of Anzio. Another tower operator said, you won’t have to worry about that; the trick is to get over the strafing abutment. His remark brought me up short! As I was walking back to the aircraft, two fighter planes came in and presently took off again; they just cleared the abutment! This demonstration certainly didn’t boost my spirits at all. Here I was about to try it with a large four engine bomber.

The fueling was completed by 1900 hours. I gathered all the crew for a takeoff briefing and explained to them once again that it was hazardous, and that I wanted volunteers. I needed the services of a co-pilot, navigator, flight engineer and radio operator. They agreed to go. I then told the four gunners, and the bombardier, that they could go back to our base at Castelluccia by motor truck. I fully realized that we could be jumped by an enemy fighter, and wouldn’t have any defense if the gunners didn’t come along. The weight factor would be approximately 700 pounds more if they came along. Considering the odds, I left it up to them. They chose to go with us.

I told the crew about pacing off the runway and about the open field at the head of the runway, and feeling that if we took off, starting from that open field we could do it. I didn’t mention to them about my marker truck along the runway that I was going to use as my reference. I was afraid that the co-pilot might not think we were buoyant at this point and might apply the brakes. So often it is the case where two people are left to make a decision, many times an unnecessary choice is made, and it was for this reason that I kept the marker truck to myself. I then told the crew to gather all the movable gear from the waist and tail sections and bring that gear up to the flight deck. I also informed them that I would zigzag the ship out on the open field in order to loosen stones and turf that might otherwise be caught in the propellers, and that they (the crew) had to pick up the loosened debris from our take off path. They would then get back into the aircraft and prepare for takeoff. After zigzagging and debris clearing, they returned to the aircraft. I then told everyone to ride up on the flight deck, and not to move under any circumstances.

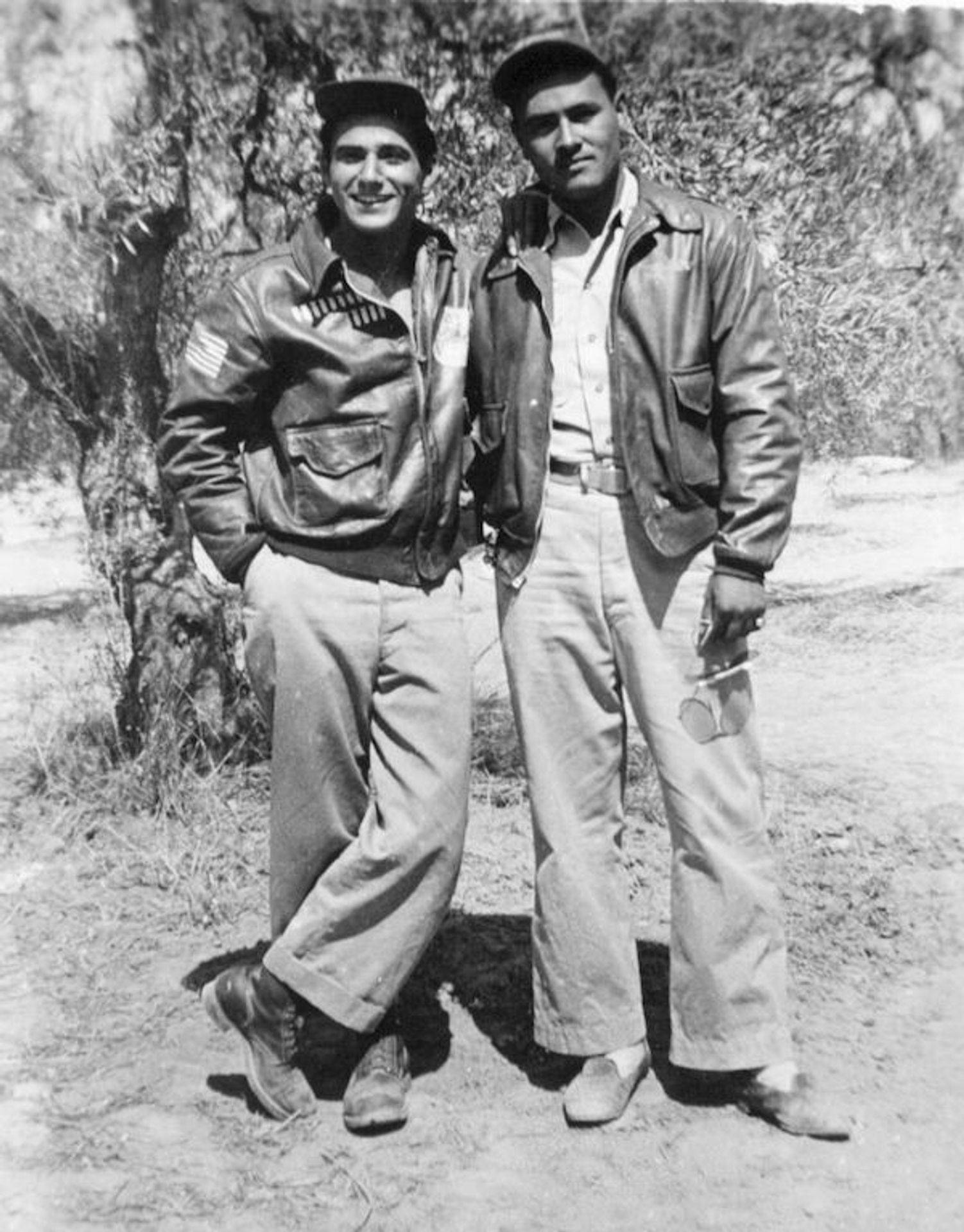

I locked the brakes and turned around in my seat to face the bombardier, Lt. Ascenio (pictured at right, holding sunglasses), who rode on the flight bench on takeoff. I said to him, “Ace, it may be embarrassing to you to say your Rosary in front of all the rest back on the flight deck, but as a personal favor to me, I would appreciate if you said it.” I told him we needed all the help we could get. He was a religious man and I respected him for it. As I turned back in the seat the co-pilot looked at me and said, “Lieutenant Martin, do you really feel confident that we can make this take off?” I told him that I had made many locked brake take offs (but to myself, I didn’t have to clear a 25 foot wall.) He said he had five little daughters at home, and they hoped they would see their Papa at the end of the war.

This statement hit me like a hammer, as I had never before, nor since, been placed in such a predicament. Most of my crew were single, except for Paul McMillen, one of our gunners. I looked at this man, and I was filled with compassion. I recklessly said to him that under the circumstances, he was free to disembark then and there, and that my flight engineer would sit in for him. He said that it had just struck him, as he looked down the runway and saw that big ominous wall, this was going to be a dangerous take off. He said, “Well, if your crew has this much confidence in your ability, far be it from me to get off.” I then explained to him and the flight engineer the “drill”.

We would go down the runway and at the buoyancy point, I would attempt to “leap frog”. They knew what I meant: I would pull back on the stick at the right moment, get the aircraft stalled in the air, then forced to stick forward and bounce the aircraft back on the ground, thus forcing the hydraulic fluid and entrapped air in the wheel strut to compress (much the same as a shock absorber), then immediately pull back again on the stick. The wheel struts, when compressed would act like a spring and when elongated, give me the extra thrust upward, similar to a bad “circuit and bumps landing”. Only in this case, I would purposely affect a hard bounce, but would be practically stalled. Upon the final pull up the engineer was to lift the landing gear. If the aircraft failed to stay in the air, we would slide to a stop on its belly, and hopefully, stop as quickly as if the wheels were down and we were applying the brakes. We went through the checklist, and when it came to the flaps, I told the co-pilot to give me 20 degrees; this would give the aircraft a steadying effect in a stalled condition, as I had to balloon this take off, and hopefully, not drop a wing. Just before I received the green signal from the tower Aldis Lamp, I noted that a strong headwind had sprung up, and this being only 2000 hours, I figured it would be a fluke, but felt that it was a good omen.

I opened up all throttles until I thought pistons and rods would fly out. I got the Aldis signal and said to myself, “Dear God, I’ve committed my life and nine others into your care. I hope it isn’t to Valhalla.” The roar of engines putting out full power, the exhaust fumes, burned oil, and dust into the aircraft, from a dirt field, didn’t make me wish to linger. I knew that the longer we stayed, the greater the possibility of injuring a propeller by sucking up a stone or chunk of hard sod. I released the brakes, and with a “swoosh” we started from the field toward the strip. As we crossed on to the strip, we were picking up speed rapidly. When we passed beside my buoyancy truck point the aircraft felt light. I also noticed a sea of faces alongside the strip. I pulled back on the controls and felt the aircraft rise. I then pushed the stick forward and slammed the aircraft back down onto the runway. I immediately pulled back on the stick and felt the ballooning effect. We must have gone 20 feet into the air. It seemed like an eternity that we hung on the props, but it was only seconds. The flight engineer pulled the gear lever, and I eased the nose slightly downward in order to gather more speed and kept it close to the strip and at the last moment, as I approached the wall, I pulled back on the stick and over the wall we went. It was much the same as one would do hedge hopping, except in this case, I wasn’t traveling at much more than stalling speed. My judgment in having all the crew and loose gear up on the flight deck paid off, as I was told later that the tail just cleared the abutment. I was too intent on keeping the aircraft flying in a tight 180 degree turn to notice too much of the airstrip, or the big bettors left behind.

As soon as we were straight, level, and back on course, I throttled back and milked the flaps back up to 5 degrees and cut back on the prop pitch to 1600 RPM. This, I had found in the past, gave me the best economical “slow fly” attitude. I then told the gunners to take their positions as we might encounter some enemy opposition. By now it was getting quite dark, and I didn’t have any illusions about being allowed to land at Naples. It was total darkness when we approached Naples Airport, and immediately the searchlights picked us up. The cockpit lighted up in an eerie manner, making it difficult to read the instruments. I called the tower and asked for permission to land. Their reply was, “Who are you? What are you? What is the identity night color code?” I responded straight off that I didn’t have the code and explained the particulars of why I had to land. They told me to move on to our own base and be prompt about it or they would shoot me down. I knew better than to try to reason with them, so I straight away headed for Castelluccia air base (left).

I asked the flight engineer for a fuel reading and his reply was that he thought that we had about three hundred gallons. I guess we all held our breath until we were in sight of our own airstrip. We called “Hiccup tower” and told them who we were and gave them our day color code, my name and squadron number. They said we could land, but all they could offer us in the way of landing lights was a Jeep’s headlamps. I didn’t bother to make any approach pattern, but just headed it down and in. I turned the landing lights on momentarily before we touched down, then turned them off (I had no intentions of being tracked by an enemy night fighter), by which time the Jeep had gotten into position. I brought the aircraft to a complete stop, said a prayer of thanks, and waited for the Jeep to approach. The men in the Jeep came up with machine guns pointed and asked us to kindly get out and identify ourselves. This we readily complied with, and after they were satisfied, we got back into the aircraft and followed them to the hard stand where the aircraft is normally parked. We checked the fuel reading, and it registered empty! It was a weary, tired crew that left the aircraft, and we didn’t bother to have our normal “bull session”. We had had a very hard, harrowing day.

The next day I turned in my report, but failed to get in touch with the co-pilot to adequately thank him for his cooperation in the blind trust that he had placed in my ability. Here was a man who had taken my word on face value – from a total stranger. That took courage. I shortly afterwards tried to get in touch with him, but he had gone off on rest and recuperation (R&R) to the Isle of Capri. I envied him; as I was not due to go until July. The trick was now to stay alive until July. Some years ago I lost all my records and books in a robbery, and with that theft went much of my past identity. Over the years I have frequently thought of this mission and after considering all the ponderables, I can only come to one conclusion – that the Good Lord was lending a hand:

1. We could have run out of fuel in any number of places other than Anzio would have had to ditch… we didn’t!

2. Anzio was in allied hands and had a landing strip, however small… we used it!

3. The British could have given us more fuel, and we might not have been able to clear the strafing abutment… the balance was right!

4. The unprecedented early evening headwind sprang up at the propitious moment before takeoff… a premium gift!

5. The fact that this takeoff was successful… was another pair of hands on the controls?

6. We arrived back at our Castelluccia base with just enough fuel… another bit of irony?

All of the above we’re just too pat; the pieces of the puzzle fit together too well for me to say it was just luck. I am convinced that God had a hand in it. He must have had big plans for someone a board that aircraft, and I was merely the steward to bring those plans to fruition. I was later awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for accomplishing this mission, and to this day I still feel surrogate to the Real Pilot.

Members of the May 26, 1944 crew were:

Pilot – Jonathan S. Martin, “Jack”

Co-pilot – ?

Navigator – Robert Wohl, “Bob”

Bombardier – Felix Ascenio, “Ace”

Flight Engineer – Charles Jackson, “Charley”

Radio Operator – Marion Moorehead, “Buzz”

Nose Gunner – Meron Landon, “Shorty”

Top Gunner – Robert Martin, “Dilly”

Waist Gunner – Andrew McGowan, “Red”

Tail Gunner – Paul McMillen, “Mack”

I am now in the twilight of life and in looking back down those years, the most gratifying period was the time I spent with the 451st. I do not believe any pilot could have asked for a better flying crew than the one I had. We received no dollars for the bombs dropped, nor did we throw our arms around each other when a special feat was accomplished. It was expected of each of us to do his best and hang in there together. I might add, that feeling epitomized the whole 451st, as the records show.

If any of you readers have been told of this fight by someone – perhaps by the co-pilot, by his daughters, or by someone who heard the story from him; would they please write to Jonathan S. Martin, Care of: 451st Bomb Group (H), Ltd. 1032 S. State Street, Marengo, IL 60152

Above story, published in 1986, was very kindly supplied by Robert Karstensen, editor of 451BG newsletter “Ad-Lib”

Robert Karstenson’s Mission with Jack Martin and crew

Captain Henry G. Rollins’ Crew 724BS 451BG

Standing: Rollins – P, Dilks – N, Snow – CP, Miller – B

Kneeling: Morrill – BTG, Gardner – AEG, Paonessa – RO, Cegla – TG, Bob Karstensen – NTG, Kalik – TTG

Perhaps the reader, after reading the preceding saga of a mission that came within a hair’s breadth of ending at the base of a strafing wall, would like to turn his attention to the following narrative (almost comical, except for the enemy involvement). This concerns the same pilot, First Lieutenant Jonathan S. “Jack” Martin, and most of the same crew; with the exception of the co-pilot, which was in this case, Second Lieutenant Willard B. Becker.

I, Bob Karstensen, was cast in the role of spare gunner, flying the nose turret. The date was 30 July 1944 and the target was located in the Budapest area. This was to be my first experience flying as a replacement gunner. My crew’s pilot, Captain Henry G. Rollins, had been tapped for duty as Operations Officer in the 724th, and from that time on our crew that had trained together at Gowen Field, saw limited duty as a unit. Though apprehensive about someone else being at the controls on this mission, I felt that Captain Rollins would make sure that I was flying with the best. This idiom, true or not, stuck with me throughout all my missions, for during my tour I flew with no less than 13 different Aircraft Commanders. Had I not maintained this attitude, I don’t think I could have completed my missions, and still felt at ease with all these different pilots.

We took our positions, me stepping on the bombardier’s bomb sight to get into the nose turret (pictured at left), and he, slamming my doors and vowing never to let me out. Test firing over the Adriatic, and then shoving our noses over Yugoslavian coastline in search of our Hungarian target. Along about this time even after scanning the skies with a neck that is weary and tired, and eyes that were becoming drowsy from the monotony and cold, a fear grabbed me when I heard either Lieutenant Martin or Becker say, “Fighters in the area, keep alert.” Boy, when those words register, the thoughts of any discomfort disappear fast. The head swivels twice as fast and the eyes cover more sky than you can imagine. Then they came, suddenly out of the sun, at about 11 o’clock high roars four ME-109s. Before I had a chance to “draw a RAD and a half bead on ’em”, they had passed through our formation and settled in on a formation low and way behind us. How they had penetrated our group and passed within hammer throwing distance from our #4 position, I couldn’t imagine. Looking at the rest of our formation I could see that no other turrets were tracking them, so they must have eluded the rest of the gunners as easily as they did me. It was just a “quick in and out”, with no harm to our group.

We reached the IP and took a course for the target. It was about then that “things” began to happen. Flak quickly found our elevation as we steadied in on our bomb run, and you could hear (and see) what the Germans were offering us. The krr-uump of the flak making a sound like gravel hitting a tin roof. This could be heard, even though our leather helmet was strapped so tight for fear of missing some inner phone conversation; especially if it was pertinent to our immediate safety. Through this maelstrom we continued, holding our #4 slot against all adversities. Suddenly, from my nose position (and the pilot and co-pilot had the same view) we saw the lead ship take a hit. Not having flown with Lieutenant Martin before, I had to marvel at the tight formation flying he was performing in the #4 slot. He had me and the tail gunner on the lead ship swapping hand signals (mostly “get away”). Now with the #1 ship in distress, I was hoping our pilot hadn’t been quite so good in his formation flying. But being that we were about to call “bombs away”, Lieutenant Martin continued to hang with him. For what seemed an eternity we clung to the leader in our #4 slot, paying little attention to anything else. The fascination of seeing a ship emitting bomb bay smoke, wondering just how long he could hold on, and realizing the frenzy that must be going on aboard – plus the calmness of the command pilot – just left you mesmerized. Whoever was in command had the presence of mind to continue the bomb run and drop on target. All the time we were clinging to our position like a terrier dog, and dropped our bombs in unison to his drop.

B-24 from the 451BG just before “Bomb’s Away!”

Now our main duty was done, and Lieutenant Martin had a moment to shift his eyes, noting that no evasive action was being done, and wondered why? One sweep of the horizon revealed our situation… we and the lead ship were all alone! It seems that when the lead ship caught the flak the rest of the formation had departed, leaving Lieutenant Martin with his eyes riveted on the #1. The two of us now made up the total of the original formation. It didn’t take long to appraise our situation, and pull the hell away. Now a new problem confronted us; would a different formation accept us? There had been a rumor that the Germans were sending captured B-24s up to join in our formations, and then from a close up position, shooting down our unsuspecting aircraft. Too, the German fighters were still in the area, and were hungry for straggling B-24 bombers.

We left our unsafe position, perhaps to involve ourselves in another untenable situation, but one that had to be attempted. Over the intercom I could hear Lieutenants Martin and Becker discussing the merits of trying for one formation or the other as they passed our view. It was a decision that had to be made, and made fast. To hesitate too long was to give the German fighters a situation they were looking for. And from my vantage point, I could see several B-24s “going down” ahead of us, and was hoping that Martin and Becker would come to a decision, and soon! They did… for off to our left and a bit below our altitude I saw a homeward bound formation of about 10 to 12 B-24s, which we headed for. From here on out it seemed like a “Chinese fire drill”. For before we gained the safety of the formation (by the way, they accepted us without challenge) about 5 other errant B-24’s had tacked on. If there was safety in numbers, we surely had it. Our new found formation had about 17 ships before we left the target area. Some of them were our earlier dispersed 724th boys. No sign of the lead ship, though.

Again, on the way home we were to encounter more ME-109s. This time they were easily spotted and were subjected to a maelstrom of 50 caliber machine gun fire. Six of them made a halfhearted pass at our formation, more out of curiosity than of vengeance. Probably never saw so many B-24s flying in one bunch, and wanted to see if we were doing it with mirrors. When we hit the coastline of Italy the formation separated and went to their respective bases. We landed without incident at about 1430 hours. We then looked over the ship for flak damage… noted none of importance… just holes for the sheet metal man to fool around with.

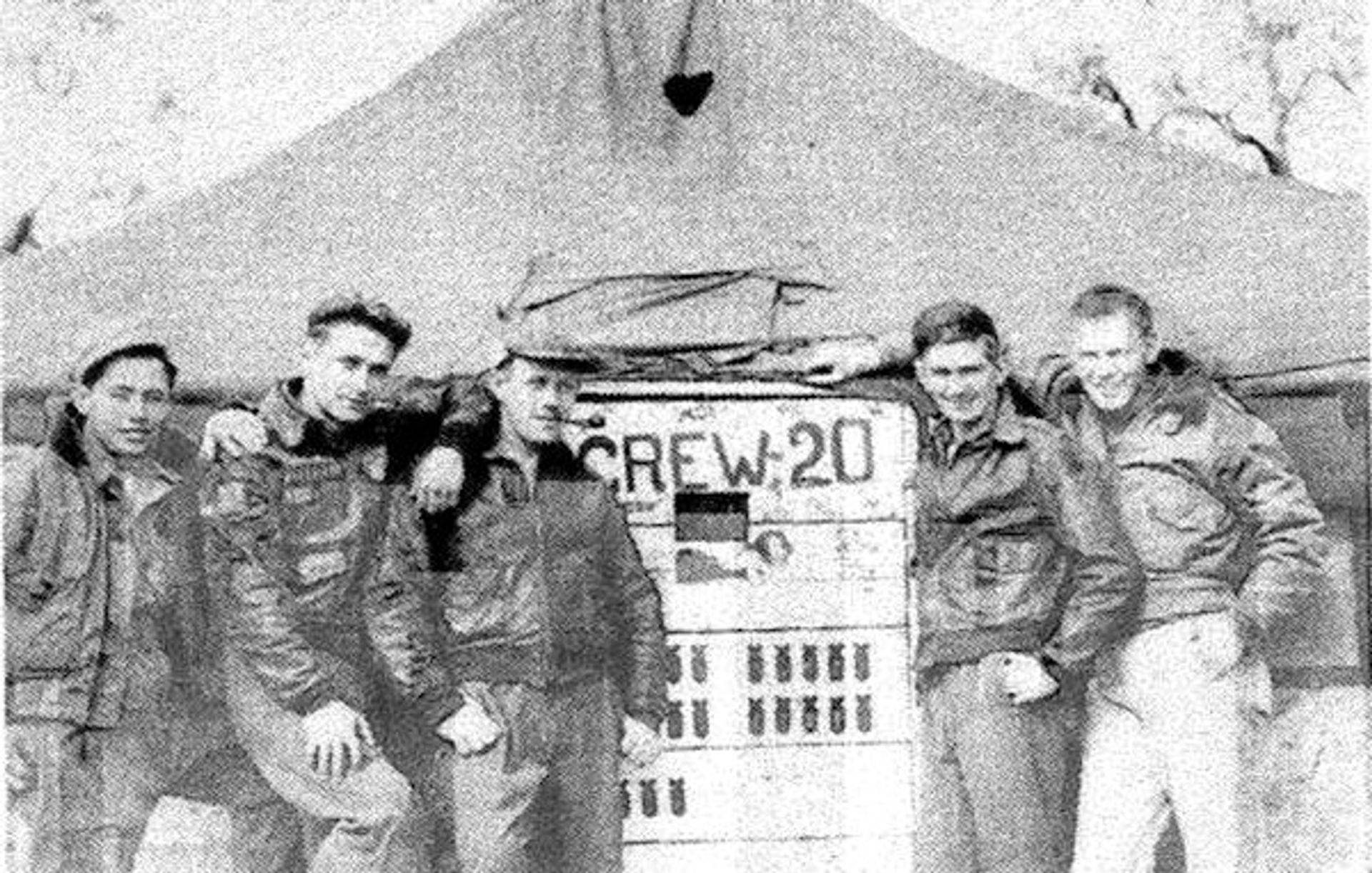

Surviving Enlisted Members of Crew 20

Leo Cegla, Andy Kalik, Fred Gardner, Eldon Morrill, Bob Karstensen (Anthony Paonessa KIA 29 Dec 44)

Thus ended my first experience as a spare gunner. I was glad it was with pilots as good as Lieutenant’s Jack Martin and Will Becker. It made me appreciate the fact that Captain Rollins, though an excellent pilot, could in some situations and emergencies be equaled. Of course, almost each mission has its fighters and flak, and in my humble estimation, each can be considered an emergency. At least from then on out, I never had to be led blindfolded to the ship and carried aboard. Jack gave me that much more confidence.

Like Jack, in his final plea for the name of his 26 May 1944 co-pilot, I too would like to find out the crew that manned the lead ship on that infamous mission. I’m pretty sure they survived – perhaps by making it to Russia, or by gaining control over their situation, they got back to the base.

Above story, published in 1986, was very kindly supplied by Robert Karstensen, editor of 451BG newsletter “Ad-Lib”