Hancock Crew – Assigned 755th Squadron – May 9, 1944

Shot down August 6, 1944 – MACR 7891

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Crew Position | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1Lt | Thomas E Hancock | 0460899 | Pilot | 06-Aug-44 | POW | Stalag Luft III |

| 2Lt | Leonard B Lent, Jr | 0819834 | Co-pilot | 06-Aug-44 | KIA | Washington DC |

| 2Lt | James O Marburger | 0707955 | Navigator | 06-Aug-44 | KIA | Cistern, TX |

| 2Lt | Edward O Centola | 0706697 | Bombardier | 06-Aug-44 | KIA | Glendale, NY |

| T/Sgt | Addison E Hart | 12082020 | Radio Operator | 06-Aug-44 | KIA | Ardennes American Cemetery |

| T/Sgt | Glenn E Newcomb | 17110595 | Flight Engineer | 06-Aug-44 | KIA | S. Minneapolis, MN |

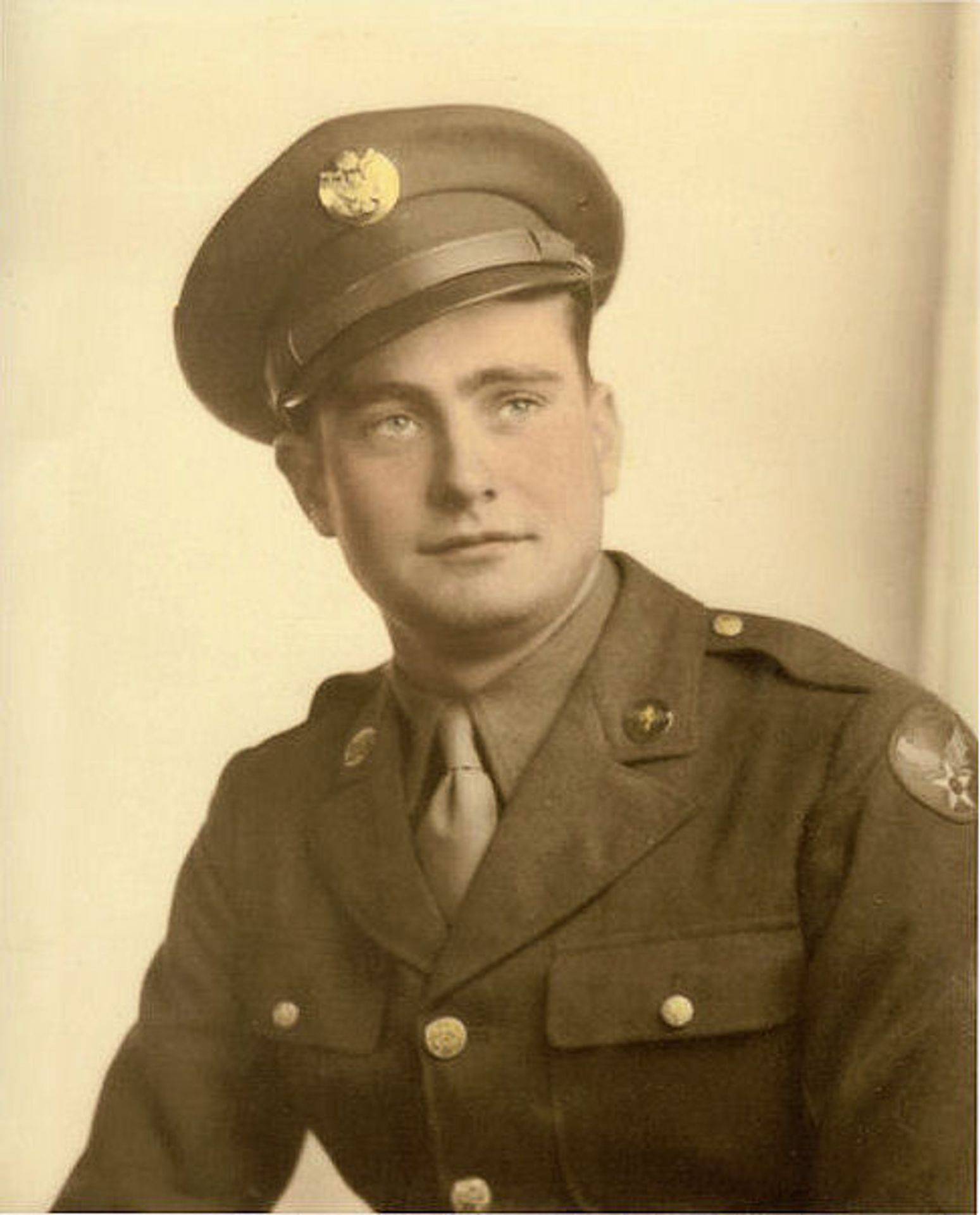

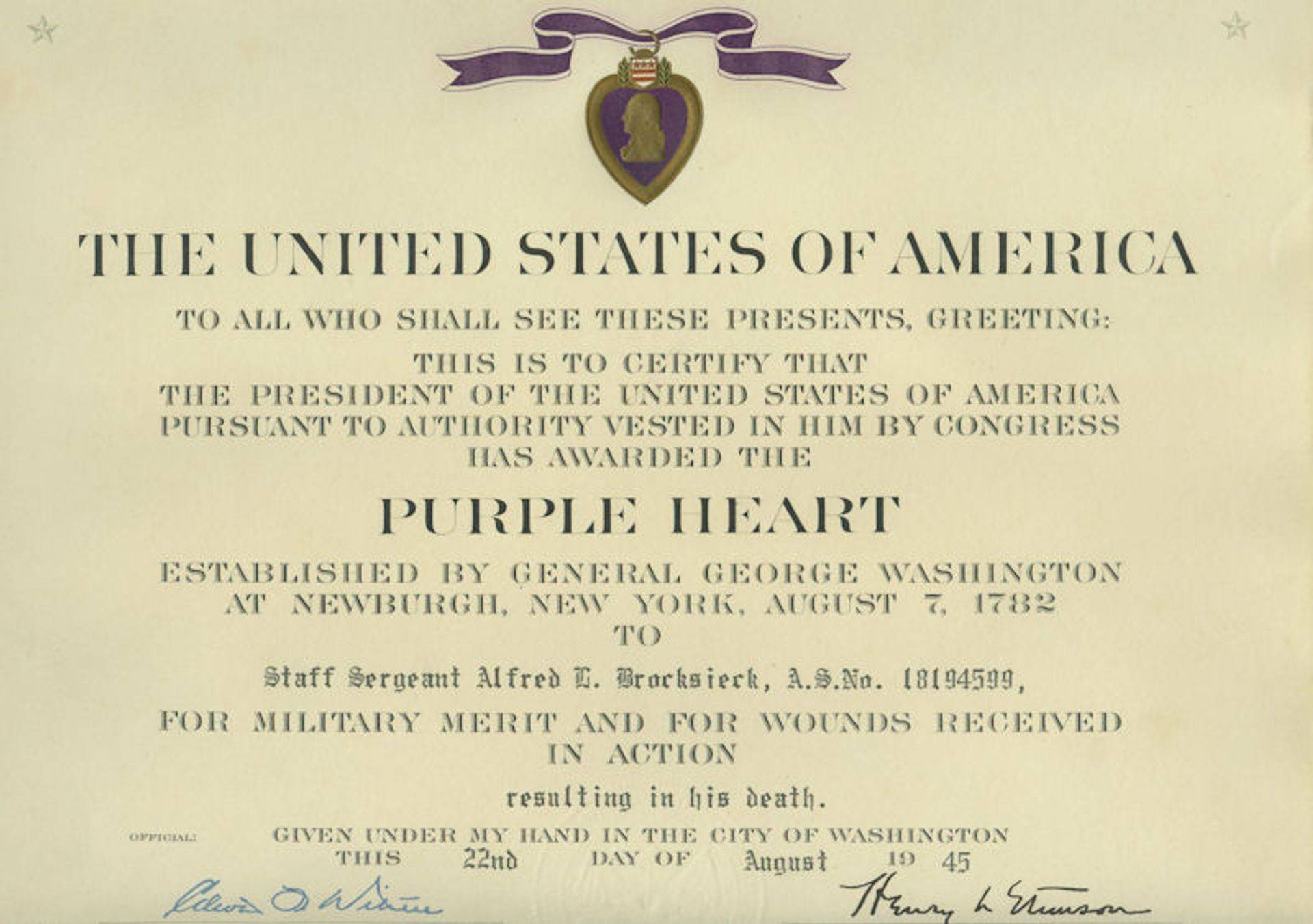

| S/Sgt | Alfred L Brocksieck | 18194599 | Waist Gunner | 06-Aug-44 | KIA | Sparks, OK |

| S/Sgt | Charlie W Carter | 14167672 | Aerial Gunner, 2/E | 06-Aug-44 | KIA | Camden, SC |

| S/Sgt | Lorinzo D Charles | 37494596 | Ball Turret Gunner | 06-Aug-44 | KIA | Macon, MO |

| S/Sgt | Charles Vlahos | 32630859 | Tail Turret Gunner | 06-Aug-44 | KIA | New York, NY |

On May 9, 1944 Thomas Hancock and crew were assigned on Detached Service (DS) from the 491st Bombardment Group and placed in the 753rd Squadron. On May 26th the entire crew was transferred to the 755th Squadron. The crew flew their first mission on May 27th to Neunkirchen, Germany.

Ten missions, including two on D-Day, followed in June. The crew flew lead on the June 17th mission to Guyancourt. Their one and only abort occurred on August 4th when they were flying in the Deputy Lead position of the second section with Captain Leland Griffith as command pilot. The crew were forced to turn back due to “…excessive vibration in #1 engine, oil pressure dropped to 30 pounds.” After landing, the “crew chief reported that the valve actuating rocker shaft pin was broken on #5 cylinder… and needed replacement”.

As a lead crew, Hancock was assigned a pilotage navigator. 2Lt Robert A. Craig, the bombardier on the crew of Lt Joseph H. French, received rudimentary training in how to navigate using maps and landmarks on the ground, and was moved to this crew. His usual position was in the nose turret.

Two days later the 458th’s target was the RHEUANIA Oil Refinery in Hamburg, Germany. Leading the 2nd Squadron was Hancock with Captain John E. Chamberlain, one of the Group Operations Officers flying as Command Pilot. The crew made it to the target, but sustained a direct flak hit just 30 seconds away from the bomb release point. The moments after that are very vividly described by Captain Chamberlain in the narrative below. Only he and pilot Hancock survived.

DEBRIEFING NOTES

Capt Richard D. Harland [Bombardier], Deputy Lead, took over on last 30 seconds of bomb run when lead ship was knocked down by flak.

————————-

MACR 7891

Lead A/C suffered a direct hit by flak on bomb run to target. The A/C exploded, wings fell off and A/C was seen heading for ground in flames. A gunner on Lieutenant Dane’s crew, A/C 126, and Sergeant Taylor of A/C 108 were the only ones reporting ‘chutes seen. The former reported one and the latter two.

Missions

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27-May-44 | NEUNKIRCHEN | 48 | 1 | 42-51097 | T | J3 | 9 | UNKNOWN 022 | |

| 30-May-44 | ZWISCHENAHN A/F | 51 | 2 | 41-29470 | O | J3 | 4 | UNKNOWN 013 | |

| 31-May-44 | BERTRIX | 52 | 3 | 41-29288 | L | J3 | 22 | BIG-TIME OPERATOR | |

| 02-Jun-44 | STELLA/PLAGE | 53 | 4 | 41-29288 | L | J3 | 23 | BIG-TIME OPERATOR | |

| 06-Jun-44 | COASTAL AREAS | 56 | 5 | 41-28682 | I | Z5 | 33 | UNKNOWN 003 | MSN #1 |

| 06-Jun-44 | PONTAUBAULT | 58 | 6 | 41-28719 | Q | J3 | 32 | PADDLEFOOT | |

| 08-Jun-44 | PONTAUBAULT | 60 | 7 | 41-29288 | L | J3 | 26 | BIG-TIME OPERATOR | |

| 11-Jun-44 | BEAUVAIS | 63 | 8 | 41-29342 | S | J3 | 22 | ROUGH RIDERS | |

| 12-Jun-44 | EVREUX/FAUVILLE | 64 | 9 | 41-28719 | Q | J3 | 36 | PADDLEFOOT | |

| 17-Jun-44 | GUYANCOURT | 67 | 10 | 41-29359 | -- | J3 | 42 | TAIL WIND | LEAD |

| 18-Jun-44 | FASSBERG A/D | 69 | 11 | 41-29359 | J | J3 | 43 | TAIL WIND | MSN #1 |

| 19-Jun-44 | REGNAUVILLE | 72 | 12 | 41-29359 | J | J3 | 44 | TAIL WIND | MSN #2 |

| 20-Jun-44 | NOBALL FRANCE | REC | -- | 42-95316 | N | J3 | -- | PRINCESS PAT | MSN #3 RECALL |

| 12-Jul-44 | MUNICH | 89 | 13 | 42-100425 | D | J3 | 17 | THE BIRD | |

| 18-Jul-44 | TROARN | 93 | 14 | 42-110184 | F | J3 | 14 | GWEN | |

| 20-Jul-44 | EISENACH | 95 | 15 | 42-110059 | E | J3 | 29 | UNKNOWN 056 | |

| 24-Jul-44 | ST. LO AREA | 97 | 16 | 42-110184 | F | J3 | 16 | GWEN | |

| 04-Aug-44 | ROSTOCK | 103 | ABT | 42-110059 | E | J3 | -- | UNKNOWN 056 | #1 ENG - GRIFFITH Cmd P |

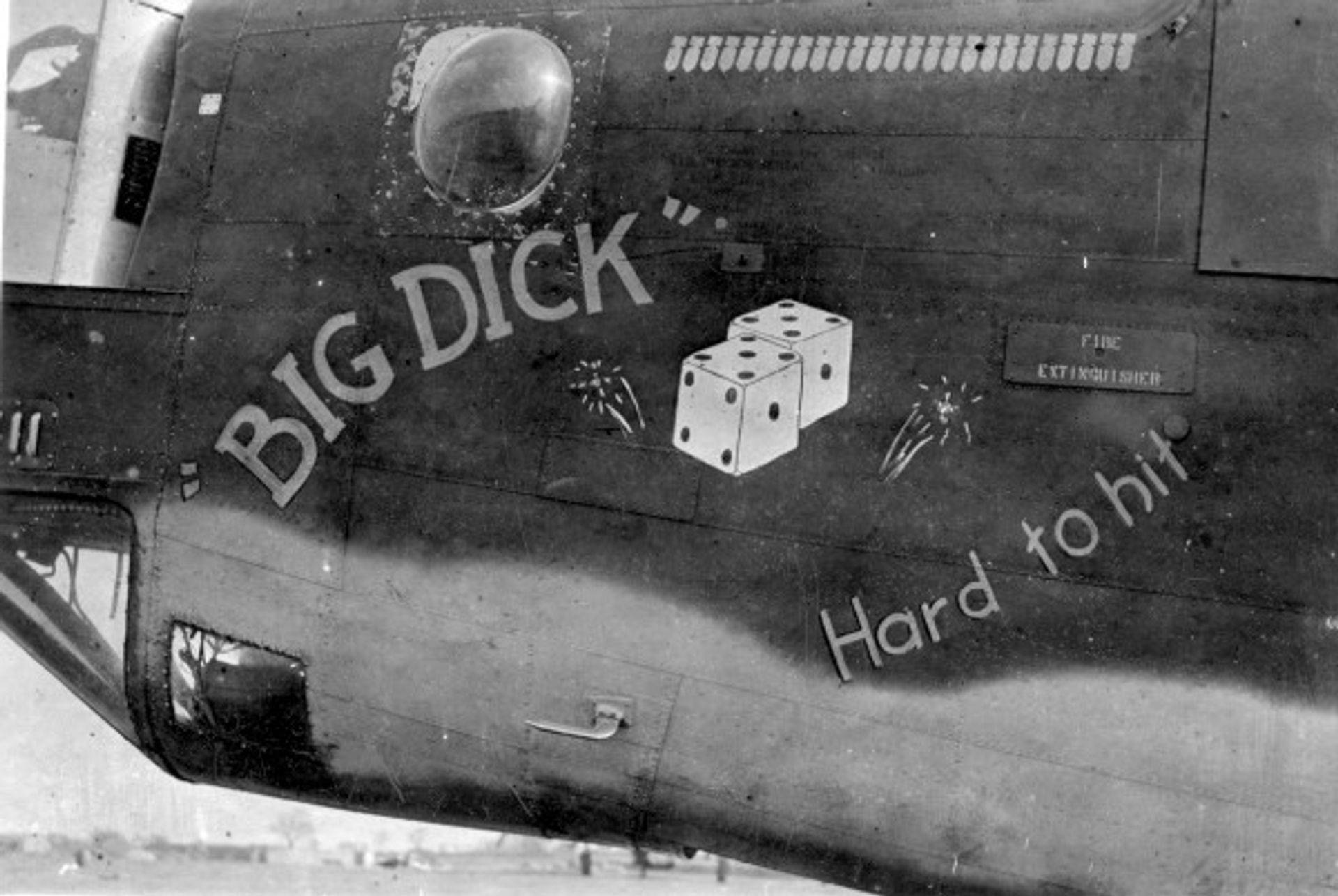

| 06-Aug-44 | HAMBURG | 106 | 17 | 42-100433 | B | J3 | 37 | BIG DICK, HARD TO HIT | DIRECT FLAK HIT - CHAMBERLAIN Cmd P |

B-24J-100-CO 42-100433 B J3 BIG DICK, Hard to hit

Named after a term in the dice game of craps, this aircraft unfortunately did not live up to its name

(Photo: Mike Bailey)

Captain John Chamberlain – Assistant Group Ops Officer

August 6, 1944 Mission Oil-Hamburg, Germany.

John E. Chamberlain, Captain USAAF

Assistant Group Operations, 458th Bomb Group

I was assigned 458 BG as a pilot and assistant group operations officer along with Captain Charles H. Booth. One of our jobs as Asst. Group Ops. was to brief the missions. We would take turns. I would brief a mission and Chuck would be free to fly. Then Chuck would brief and I could fly. It was my turn to fly this time. Chuck brief.

As staff officers we were not assigned crews. When we were assigned to fly a mission it was as a command pilot in command of a flight of more than one aircraft. The command pilot would sit in the right seat assume copilot duties and take command of the entire flight. The left seat was flown by the lead crew pilot especially trained with the crew for the job.

On Aug 6 Chuck briefed and as I had forgotten my binoculars lent me his. To this day whenever we make contact the very first comment he makes is to bitch about my never returning his binoculars. Tom Hancock crew was assigned as lead crew this mission. I was to fly as command pilot.

The flight to target was not too eventful as best as I can recall. A couple areas of flak. I don’t remember any fighters. As we approached the target however the sky was unbelievable. A solid mass of black flack bursts. We hit the IP on schedule and turned on our planned heading to the target. Time has dimmed the memory a little but at 15 seconds from bomb release – hard to describe there was a crunch we seemed to stop in mid air. An airplane to a pilot is a living operating entity of which you are apart of-this life suddenly stopped and became just a hunk of junk. No controls no nothing. Over my left shoulder I could see fire. To get a better look I opened my seat belt. A bad mistake. The ship flipped and I was thrown bobbing about like a ping-pong ball. The ship turning over and over. Flying about I could see the wings both come off. Suddenly I could see Tom flying about with me. He was able to open the top hatch. One second it would be above me-to the side-next below. Tom would try to help me thru the hatch. The ship would flip and I would fly off someplace. I would try to help him thru the hatch. The ship would flip again. Tom would be thrown aside.

Finally after it seemed an eternity I felt myself falling back towards the flame in the bomb bay. There was a gigantic burst of light and I felt myself blacking out. Time passed don’t know how long. I woke up falling through the air on my back. My first thought was. God I must be about to hit the ground. Get that chute open. I pulled the rip chord and chute opened with a jerk. It jerked my flight boots off and I subsequently walked over a lot of Germany with out any shoes.

Liberators flying through the flak at Hamburg on August 6, 1944

(Photo: Bill Kramer)

We were bombing at 23,000 feet I believe. Thereabout anyway. When my parachute opened it looked to be at around 800 or 900 ft. above the ground. At that period of time there were three types of parachutes in use. A chest type that had to be clamped when needed to the harness that the person wore, a seat type and a back pack – both fastened to their harness in those respective positions permanently and worn at all times. They stayed with you at all times but were awkward to move about with. Tom and I were both flying with backpacks, which stayed with us when we were blown out of the airplane. The ship spun and blew up so fast after being hit that there was no time for any one to find and clamp on a chest pack. All other crew members may have been wearing chest packs, as they needed to be able to move about. Exception! Ball turret gunner. Tail turret? Don’t know. Upon opening my chute the first thing I remember was how quiet it was. No aircraft no guns. Dead quiet. Then I could hear small arm fire.

Looking down I could see a person walking out of a large pond of shallow water. It turned out to be Tom. He had his arms above his head. I could see a small group standing on the bank. They were shooting into the water about him. I later found him to be unharmed. They must have been trying to scare him. I don’t see how they could miss at that distance. Looking about I saw a small group of people were running towards me. They would stop and shoot at me with small arms. I found myself trying to remember. How do you steer a parachute? Try to make a difficult target. I tried pulling here and there on the lines. Swinging. Nothing seemed to have much effect. Again they must not have been really trying to hit me because nothing touched me. I know I would not have missed had I been pulling the trigger. Descending in the chute I seemed to kinda black out briefly now and then but assessing for injuries I found a large flap of my scalp torn loose hanging down over my forehead. I patted it back in place I found that a piece of shrapnel had pierced the palm of my right hand between the 4th and 5th metacarpal to exit and was sticking out of the dorsal surface of the hand. I pulled it out of my hand and was going to save it as a souvenir but I passed out and lost it. I don’t remember landing on the ground.

The next thing I knew I was standing on the ground with my parachute off. An old guy in civilian clothes had me by the arm and was yelling at me in German. My immediate reaction was to shake him off. He fell to the ground. That precipitated a loud burst of screams. There was a deep slit trench to the right of my feet. It was filled with women and children all screaming like mad. I suppose I did look pretty rough with my scalp half pulled off and blood all over me. At that 20 or 25 German soldiers in dull blue uniforms and a few young boys in uniform all armed with rifles or burp guns pointed at me came running up. All yelling but no one pulled a trigger. They corralled both Tom and I and marched us off with hands over our heads. Ever try holding hands over your head for a prolonged period of time? Exhausting. After a time we were allowed to place hands on head. At least that is what we did and no one objected. They marched us a ways to a covered air raid shelter dug out of the ground with two bunks carved out of the sidewalls. It had an open door and slit cut out for a window. They shoved us inside and posted a guard with a rifle at the open door. We flopped down on the bunks. I passed out again. Later I was shaken awake by someone who was speaking in English. It was dark out. He asked if I was beaten by the troops or was I injured in the crash. I told him it was the crash. He stuck a cigarette into my mouth and lit it. I remember nothing more until I woke up.

It was day. The cigarette was burnt out between my fingers. They rousted us out. We were put into a truck. A rather large one with stake type sides. It was filed with straw. They had us climb in on top of the straw. We soon discovered that there were dead bodies under the straw. They drove into Hamburg to a large cemetery. Don’t remember seeing any headstones. There were large piles of dead bodies in all stages of decomposition stacked everywhere. We were forced to pull off the straw and set about trying to identify the remains. Most bodies were in pieces and badly mangled. Very difficult to identify. Some had dog tags. Most did not. Tom tried to identify those who did not. I was not much help as not being a member of Tom’s crew I had never known any of them before this. Two members were missing. We did not tell the Germans who in case they had evaded. We told the Red Cross later after enough time had elapsed to facilitate escape – if by some miracle they had. The Germans then had us carry the remains over to an empty spot. We did so. I said a little prayer.

We were then loaded back onto the truck and we drove farther into Hamburg. They drove us around for a while showing us the terrible destruction we and our kind had done. We were delighted to see the beating we were giving them. They drove us to a building and put us with a group of other prisoners shot down elsewhere. One poor guy was lying on a blanket unable to stand or walk. He had landed in his parachute among a group of civilians. He had been stabbed numerous times with ice picks or screwdrivers. I was ranking officer in the group. I complained to everyone I could find demanding medical help. After a 2-day wait they took him away to a hospital they said. I never saw him again. We were in a few days taken to Dulag Luft, an interrogation center in Frankfurt on the Main. Another story.

Courtesy: John Chamberlain, 2003

S/Sgt Alfred R. Brocksieck

Sgt Addison E. Hart

Ad’s Description of His Crew – England 1944

Our pilot, 1st Lt. Tom Hancock is from Florida. Sort of a stocky built guy – not fat though. I wouldn’t want to tangle with him. He’ married – due to be a poppa in a month. I’ve met his wife – a pretty blonde girl – she seems very small next to him, saw them on the street in Charleston one day. He was a 2nd Lt. in a Field Artillery outfit before he transferred so he knows the Army ropes. We all have the fullest confidence in him, we know from comparison to flying just once in combat here with another pilot.

Co-pilot 2nd Lt. Leon Lent – a cocky little guy from Washington, D.C. Strictly a fighter pilot type – jumpy, smart-aleck, backfire comebacks to mostly anything you say. A competent pilot but needs experience. His dad is a Brig. Gen in Wash. So therefore Leon wants to hear that, “Sir” when you speak to him among other officers. He’s a good guy – always good for a laugh. Oh – he’s not married.

Navigator is 2nd Lt. Jim Marburger – a Texas boy. We all have yet to hear him cuss – and hope we never do. He’s sort of tall with close cropped or maybe short cut hair and as handsome as they come. What that guy doesn’t know about navigation “jes ain’t worth knowin”. He was top man in his class in cadets. He’ll fuss and fume if we’re five degrees off course or a few minutes late.

We have a new officer – Lt. Craig – pilotage navigator. Lead crews carry the extra navigator to spot the target visually for positive identification. He seems like a regular guy – although we haven’t known him long, I think he’s pretty much on the beam.

Our bombardier is a little short chunky fellow from N.Y. City. Lt. Centola – only 19 or 20. In the States he was a little brass happy. “I’m an officer – I’ll stay in my place – you stay in yours.” Didn’t have much to say then, but what a change now! Without the bar on his collar he could get through a G.I. chow line, shootin’ the gab with the best of them with no effort or trouble at all. He knows his bombsight, but needs some practice flying the A-5 and C-1 auto-pilot. Nicknamed “Cricket” by Charlie.

And the T/Sgt radioman I guess you know, or if you don’t then make it a point to know him better when he gets back.

T/Sgt Glen Newcomb, our engineer, is from Minnesota. A crew couldn’t ask for a better engineer. As an engineer he knows his work, but there we stop. Forever and always, incessantly he’s worrying about someone else’s business. He’s too eager for work, got to know what goes next, are we alerted – when is radio school for me, turrets for the other fellows. I think he’s afraid of his stripes – afraid of losing them, which is silly. Hancock unknowingly encourages this “look after” attitude. “Get your boys down there on time” – and the like. It’s always your boys, not “you boys”. But I’d better not get started on that – I get hot when I start talking about him that way.

Which brings us to the boys in the aft bomb bay positions…

S/Sgt. Al Brockseick – “e” is silent. Brock or Stretch, our right waist gunner, is from Oklahoma. A tall, lanky guy with that western slouch of a walk. His initials are A. L. – says, “they used to call me Al till somebody told me to ‘git the ‘L out of there’”. He’s not married – got a girl back home. Brock’s always comin’ out with some humorous remark that characterizes the west – some are tainted you might say, but nonetheless colorful.

The Charlie I mention so often is S/Sgt. Charlie Carter, left waist gunner from S. Carolina. He’s around 27-28, married and got a boy 4 years old. He is the talkin’est man I’ve ever seen. He’ll talk the ears off a brass monkey if it would sit still long enough. What a line he shoots these poor Limey gals – and they take it all in, seemingly comin’ back for more.

Ball gunner is Lorenzo Charles – Staff – Yep, that’s his last name, Charles. He’s also married and has a boy – home is in Missouri. Used to work for a construction company and if you let him he’ll tell you every detail of a job, sidelights on the family, skunks, his car, etc. far into the night. Mostly he throws “chaff” out the chute when we get near the target. Chaff is metalized strips of paper 1/8” wide by a foot or so long to jam the enemy radar screen with many “pips” or signals to thrown off the ack-ack guns. It is positively a pleasure to see that flak following the chaff way below us. It is especially effective when we are above the clouds and they can’t see us at all.

Last, but not least in importance is our “Tail end Charlie” – literally. S/Sgt Charles Vlahos, the tail gunner – a Greek boy from N/Y/ City. Somewhat quiet, but he can argue you down on most any subject. He’s not married and a real sharp looker when he gets dressed up. He’s spotter for the bomb hits.

Thomas Hancock’s Letter to Hart’s Parents

Aucilla, Florida

July 12, 1945

Mr. Edward O. Hart

182 Mosley Dr.

Syracuse, 5, N.Y.

Dear Mr. Hart,

A few weeks ago I arrived in the States after being a prisoner in Germany since 6 August [1944]. I know how anxious you must be to hear any news regarding your son. The information I have isn’t very pleasant, and it certainly is hard for me to tell you this, but I believe you’ll want the story just as it happened.

We were leading the formation over Hamburg last 6 August, flying at 24,000 feet. Enemy flak hit the ship, causing it to explode without any warning whatsoever. I was blown out of the ship and was unconscious until I fell into the Elb River in Hamburg. The same thing happened to Capt. Chamberlain, and he landed about 200 feet from me. The rest of the crew was reported either missing or killed.

Your son was in the plane at the time of the explosion, but his body was not found. I had written the Red Cross in Geneva, Switzerland, as to the details or whereabouts of your son, but have received no information as yet. In case I should hear something I’ll let you know right away.

We learned what had happened to our ship from another fellow in our formation that day. He was later shot down and in the same prison camp with me. There he told me the story.

I wish I could have told you this in person, but it’s impossible for me to visit all the next of kin.

Before the crew was shot down we completed 17 missions. You probably have heard from the W. D. that you son and all the crew members were awarded the Air Medal with two oak-leaf clusters. Your son was called upon by his C.O. to lead his fellow men in combat. He had a very excellent rating for his duties both on the ground and in the air.

I want to thank you for writing such nice letters to my wife. I know she appreciated them so much.

I am deeply sorry that such an accident had to occur, but that is the fortune of war. If there is any further information you wish to know or if there is anything I can do, please command me.

Sincerely,

Thomas E. Hancock

1st Lt. A.C.