Crew 20 – Assigned 753rd Squadron – October 1943

(Photo: AFHRA)

Transferred to 389th BG, shot down July 31, 1944 – MACR 7747

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Crew Position | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capt | Robert E Lamb | 0438667 | Pilot | 31-Jul-44 | POW | Camp Unknown |

| 1Lt | Donald F Mallon | 0745137 | Co-pilot | Sep-44 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

| 1Lt | Thomas F Comi | 0692374 | DR Navigator | 31-Jul-44 | POW | Stalag Luft I |

| 2Lt | Herman Lodinger | 0886832 | Bombardier | 31-Jul-44 | POW | Camp Unknown |

| T/Sgt | Carl E Miller | 37216030 | Radio Operator | 31-Jul-44 | POW | Stalag Luft III |

| T/Sgt | Louis F Koch | 13113265 | Flight Engineer | 31-Jul-44 | KIA | Berks County, PA |

| S/Sgt | Marshall A Tharpe | 18134525 | Nose Turret Gunner | 31-Jul-44 | KIA | Caddo Parish, LA |

| S/Sgt | Francis J Morello | 33032764 | Aerial Gunner | 31-Jul-44 | POW | Stalag Luft 4 |

| S/Sgt | Everett M Cayford | 11029650 | Ball Turret Gunner | 31-Jul-44 | POW | Stalag Luft 4 |

| S/Sgt | Michael Kousa | 31120277 | Ball Turret Gunner | 31-Jul-44 | POW | Camp Unknown |

Robert Lamb and Crew 20 trained with the 458th Bomb Group in Tonopah, Nevada in the last few months of 1943. The moved overseas with the group in January 1944 via the Southern Ferry Route.

Crew 20 was to begin their career as a lead crew. While their tour with the 458th lasted less than 30 days, this crew flew 7 missions (including one diversion in support of “Big Week”), all of them as lead or deputy lead. On March 28th they were transferred to the 389th Bomb Group, receiving training as a PFF lead crew. As a lead crew, the co-pilot’s seat would usually be occupied by a Command Pilot, so Donald Mallon may have opted to remain with the 458th. He is listed as finishing his tour in September 1944, although which crew or crews he flew with is not documented. Moving to the 389th with Crew 20 as co-pilot, was 2Lt John Jircitano, originally on Crew 30.

According to 389BG historian Kelsey McMillan, the crew flew 18 missions while with the 389th, coming back to the 458th on 6 occasions (one of those missions being recalled) to lead their old group. Their luck ran out on July 31, 1944 while flying lead with the 453rd Bomb Group on a mission to Ludwigshafen.

Information from Tom Brittan

On July 31, 1944 while leading the 453rd BG with Major Andrew S. Low, Jr., Group Operations Officer, as Command Pilot, Lamb’s aircraft (41-28778 N YO) was hit by flak over the target, a Methanol processing building in I G Farben chemical works, Ludwigshafen, Germany. The aircraft left the formation just after bombs away with #3 engine and the bomb bay on fire. The crew bailed out except for engineer, S/Sgt Louis F. Koch who was fighting the fire in the bomb bay and the top turret gunner, S/Sgt Marshall A. Tharpe who had entered the bomb bay to help. Apparently, Tharpe’s parachute opened inside the plane, engulfed both men in flames and trapped them in the bomb bay. The plane exploded in mid-air before crashing 3 kilometers north of Viernheim, Germany. Eleven men bailed out and were taken prisoner.

The two other crew members on this aircraft were: 1Lt William B. Buchsbaum – navigator, and 1Lt Robert R. Popper – “pilotage-bombardier”. Popper was formerly of Crew 12 in the 752nd Squadron and had been transferred with them to the 389th in March.

————————-

MACR 7747

Lead PFF went down just after bombs away. [Number] 3 engine on fire and bombay [on fire]. A/C eased out of formation then dove straight down, 7 possibly 8 chutes seen.

Missions with 458BG

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Cmd Pilot | Ld | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25-Feb-44 | DANISH COAST | D2 | -- | BOGUSCH | D2 | 42-100341 | -- | J4 | D2 | SATAN'S MATE | Diversion Mission |

| 03-Mar-44 | BERLIN | 2 | 1 | BOOTH | D2 | 42-100341 | -- | J4 | 2 | SATAN'S MATE | |

| 06-Mar-44 | BERLIN/GENSHAGEN | 4 | 2 | MASON | D1 | 42-100431 | B | J4 | 1 | BOMB-AH-DEAR | |

| 09-Mar-44 | BRANDENBURG | 6 | 3 | HENSLER | L2 | 42-100341 | A | J4 | 4 | SATAN'S MATE | |

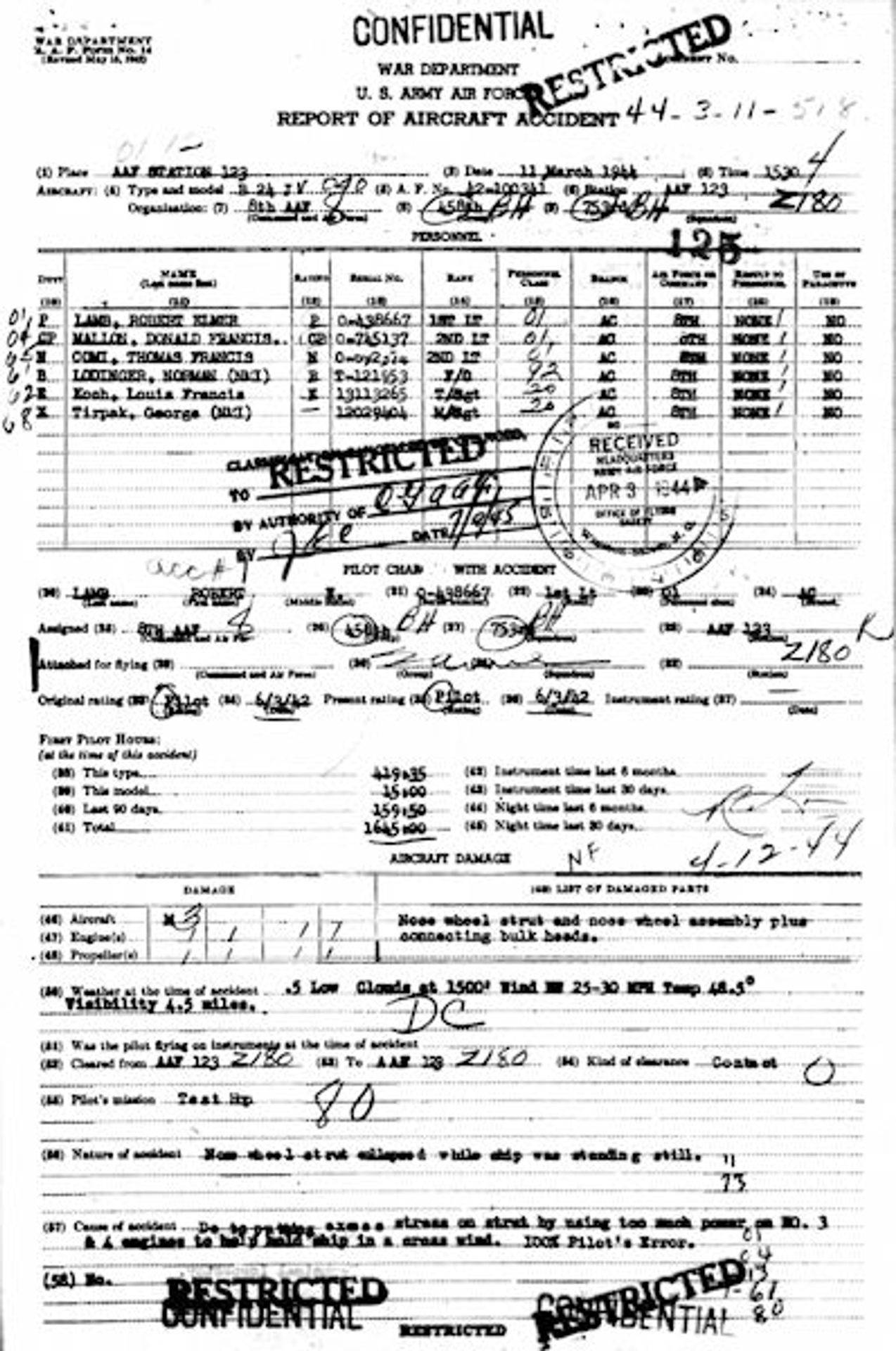

| 11-Mar-44 | Non-Operational Mission | -- | ACC | 42-100341 | A | J4 | -- | Satans's Mate | Taxiing Accident AAF 123 | ||

| 16-Mar-44 | FRIEDRICHSHAFEN | 8 | 4 | FEILING | L1 | 42-100431 | B | J4 | 3 | BOMB-AH-DEAR | |

| 23-Mar-44 | OSNABRUCK | 12 | 5 | HOGG | L1 | 41-28676 | C | YO | -- | 389BG - PFF SHIP | |

| 24-Mar-44 | ST. DIZIER | 13 | 6 | MOORE | D2 | 42-100431 | B | J4 | 6 | BOMB-AH-DEAR |

Missions as Lead with 389BG

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Cmd Pilot | Ld | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 08-Apr-44 | BRUNSWICK/WAGGUM | 17 | 7 | JAMISON | D1 | 41-28713 | G | -- | PFF - LED 458BG | |

| 13-Apr-44 | OBERPFAFFENHOFEN | -- | 8 | 41-28714 | G | YO | UTTERLY DEVASTATING | PFF - LED 44BG | ||

| 18-Apr-44 | BRANDENBURG | 22 | 9 | FREEMAN | D1 | 41-28715 | I | -- | PFF - DEP LD 458BG | |

| 21-Apr-44 | BRUX, CZECHOSLOVAKIA | SCR | -- | 41-58714 | H | YO | UTTERLY DEVASTATING | PFF - 458TH - SCRUBBED | ||

| 22-Apr-44 | HAMM M/Y | 25 | 11 | JAMISON | L1 | 41-28714 | H | YO | UTTERLY DEVASTATING | PFF - LED 458BG |

| 04-May-44 | WAGGUM | REC | -- | 41-28715 | I | -- | PFF - 458TH - RECALL | |||

| 07-May-44 | OSNABRUCK | -- | 12 | 41-28715 | I | -- | PFF - LED 445BG | |||

| 08-May-44 | BRUNSWICK | -- | 13 | 41-28807 | N | -- | THE VULTURES | PFF - LED 466BG | ||

| 12-May-44 | BOHLEN | -- | 14 | 41-28778 | N | -- | PFF - LED 445BG | |||

| 02-Jun-44 | BERCK-sur-MER | -- | 15 | 41-28778 | N | -- | PFF - LED 466BG | |||

| 03-Jun-44 | STELLA-PLAGE | -- | 16 | 41-28778 | N | -- | PFF - LED 93BG | |||

| 06-Jun-44 | PAS de CALAIS | -- | 17 | 41-28778 | N | -- | PFF - LED 93BG | |||

| 06-Jun-44 | COASTAL AREAS | 56 | 18 | LaROCHE | L1 | 41-28778 | N | -- | PFF - LED 458BG - MSN #1 | |

| 06-Jun-44 | PONTAUBAULT | 58 | ABT | LaROCHE | L1 | 41-28778 | N | -- | PFF - ABORT WEATHER | |

| 18-Jun-44 | HAMBURG | -- | 19 | 41-28778 | N | -- | PFF - LED 445BG | |||

| 20-Jun-44 | OSTERMOOR | 71 | 20 | ISBELL | L1 | 41-28778 | N | -- | PFF - LED 458BG | |

| 21-Jun-44 | BERLIN | -- | 21 | 41-28778 | N | -- | PFF - LED 448BG | |||

| 28-Jun-44 | SAARBRUCKEN | -- | 22 | 41-28778 | N | -- | PFF - LED 491BG | |||

| 29-Jun-44 | OSCHERSLEBEN | -- | 23 | 41-28778 | N | -- | PFF - LED 489BG | |||

| 29-Jul-44 | OSLEBSHAUSEN | -- | 24 | 41-28778 | N | -- | PFF - LED 453BG | |||

| 31-Jul-44 | LUDWIGSHAFEN | -- | 25 | Major LOW | L1 | 41-28778 | N | -- | PFF - LED 453BG |

389BG mission list generously supplied by Kelsey McMillan

B-24J-95-CO 42-100341 J4 A Satan’s Mate

Satan’s Mate flown by Crew 20 until a ground accident put her in for repair. She was lost on July 11, 1944.

(Photo: Harold Armstrong)

DESCRIPTION OF ACCIDENT

The pilot started engines in hardstand, taxiied [sic] up to the perimeter track to take off position. Brakes and throttle were not used excessively during taxiing.

Upon reaching a position just off the runway the ship was stopped and the engines were run up and checked.

After completing the run up some power was left on No. 3 & 4 engines to help hold ship against strong cross wind. The pilot misjudged the amount of power necessary and used excessive amount causing a side torque to be put on the nose wheel strut causing it to collapse. There was no indication of material failure.

It is recommended that while standing still that the aircraft be held only with brakes with no attempt be made to help by using power.

John A. Hensler

Major, Air Corps.

Technical Inspector

————————-

July 31, 1944

Chivalry in Adversity

By General Andy Low

Graduates of Service Academies have, for more than one hundred and fifty years, worn finger rings to commemorate their Alma Mater. In earlier years, before the advent of the gummed envelope, these commemorative rings served the useful purpose of imprinting the sealing wax on letters – even serving as an exterior identifier of the author. Many collegians of other institutions did a similar rite of passage. However, many of these collegians owed a closer allegiance to Greek-letter fraternities to which they belonged. Often their rings reflected this latter allegiance.

Since 1897, rings of West Point have reflected on the motto, “Duty, Honor, Country” and the Academy Crest, on one side of the ring, and a class adopted crest on the other. During the third year, great activity by each class member marks the arrival of class rings. Because of the closeness of the Academy experience – living in barracks, meals in a common mess, formations for all phases of daily life – the class ring is a ready manifestation of this closeness. Most graduates wear their rings much of the time – and certainly at activities associated with the Academy experience.

And thus, I was one who wore my class ring most of the time. In combat, in Europe, in early 1944, we were required to wear our issue name plates (“dog tags”) at all times, but we were discouraged from carrying other identification which might be “of aid and/or comfort to the enemy.”

On 31 July 1944, There was some confusion on the assignment from our Group for the Combat Air Commander. He would command the Second Combat Wing, and the Second Air Division, which the Wing would lead. As Group Operations Officer, I had been up all night during mission preparations, and thus was most familiar with targeting, routes, communications, and the myriad of details to get over four hundred Liberator bombers to the target – Ludwigshaven, and the IG Farben Chemical Works. So, I took the assignment. In a last minute rush, I changed into my flying gear and proceeded by jeep to Wing Headquarters, some ten miles down the road.

Briefing, take-off, form-up, coast-out, tight formation – all went well until we began our bombing run. We were at 24,000 feet, the highest I had ever flown on an attack. We encountered heavy flak at our altitude, and took random hits with no personnel injuries up to “Bomb Doors Open.” Just as the bombardier announced “Bombs Away” we took a burst just under our bomb-bay which set our hydraulic lines and reservoir on fire – a raging fire. The crew fought the fire but warned we were in serious condition, with a chance of an explosion of the gasoline tanks above the bomb-bay.

Quickly, the aircraft commander and I decided we had to leave the formation, dive to attempt to blow out the fire – and to clear the target area. I told the Deputy to take over the formation and we dove sharply in a sweeping arc away from the target. The Flight Engineer in the bomb-bay reported that the structure was catching fire. WE knew we had to jump, and the aircraft commander sounded the “Stand-by to bail” on the alarm, and “Jump” almost immediately.

We were three on the flight deck, the Pathfinder Navigator, the Aircraft Commander, and me. The Navigator attempted to open our normal egress through the bomb-bay the fire was just too much of a blazing inferno. I had shed my harness, and stood up as he was reclosing the door. Over my head was a hatch used on the ground during taxiing, but was not an authorized egress in the air. It was forward of the top turret, and could be blocked by guns. It was forward of the propellers – but both number two and number three engines had been feathered. There were two vertical stabilizers on the B-24J, but we found out we had already lost one in the dive. I bent down, grabbed the Navigator around the legs, and shoved him through the hatch. I followed quickly, and the Aircraft Commander was right behind me. We cleared the aircraft, pulled our ripcords – and the plane blew up.

I was alone as I floated out of the clouds close to the ground, and could see I was headed for farmland outside a village. As I neared the ground and prepared to land, I realized I was headed right at two military figures with rifles – and the longest fixed bayonets I had ever seen. I touched down, collapsed my chute, and the German soldiers were not twenty yards from me, rifles at ready.

“Haben sie pistole?” I did not understand what they said, but guessed. I shook my head and raised my arms, and then I realized I was really hurt. My flying suit was still smouldering. The Germans put down their guns and helped me beat out the embers. That done, they picked up their rifles, and began to search me. I was told to take off my watch by their motions. Then they emptied my pockets, found my dog tags but did not take them, and then helped me pull off my burned gloves.

And there it was – my West Point 1942 Class Ring. They motioned me to take it off, and it was dropped into a pack one soldier carried. As they motioned me to march, I suddenly realized how scared I really was – and fearful of what was going to happen next. We were taken to the village jail – all nine of us who made the jump. Two crewmen in the rear of the aircraft did not get out. We had all been quickly rounded up by the militia-type soldiers who had been turned out to look for downed men. From the civilian jail, we were taken to a German Air Force airfield. We were given some medical treatment, wrapped with paper bandages, and readied for a trip to the Interrogation Center. At the Interrogation Center, I was put in a plain, small solitary cell. I had told them my name, rank and my serial number. I was bandaged so that I had to have someone feed me, and help with trips to the personal facilities.

My first session with the Interrogator was brief. I repeated my name, rank, and serial number. He called me major, but said he needed to know more. As he remarked, they did not give medical treatment to spies. I hurt terribly, and was not sure what was happening under the bandages. But, I had endured West Point, and I knew they were not going to be any tougher. The second morning was a repeat, giving only name, rank and serial number, and back I was sent to my cell, still hurting.

As I thought over my situation, and what was happening to the others whom I had not seen, I realized I had been riding with a 458th Bomb Group aircrew, transferred to the 389th as a lead crew. The aircraft wreckage would have 389th insignia. I deduced therefore that they were not too sure who I was. The third day session was another repeat. But the interrogated said I was foolish, as they would find me out. No medical treatment until they did. Back to my cell.

It was a warm August evening, but from my cell I could see nothing, and hear very little. Time dragged. Suddenly, the guard was opening my cell, and in came a German flying officer. His left arm was mangled, and heavily bandaged. The guard locked him in, and went away. In excellent English, with a British accent, he asked if I wanted a cigarette. I told him I did not smoke, so that ended that entrée. I really hurt and the bandage reeked, so I was angry enough to be rude. He asked if I would like something to read – Life, maybe. I replied I could not handle book with my bandages.

He said he was sorry for me as an airplane pilot, for me the war was over. But he added, he would never fly again either. We warmed to each other – a little. He asked about my family. I told him I had a daughter I had never seen. He told me about his family. There some more small talk, and then he arose to leave. He walked to the door, and then came back to me. His good hand was in his pocket. He pulled it out and dropped my Class Ring inside my clothes.

Simply he said, “I am sure this means something to you, and it means nothing to them. Hide it, and do not wear it until you are free!” With that he turned quickly and left me alone – with my thoughts.

Can there be such chivalry among such obvious adversity? For me, there was.

Courtesy: 453rd Bomb Group Stories; Photo: In Search of Peace by Michael Benarcik

MACR Statements

T/Sgt Louis Koch and S/Sgt Marshall Tharpe did not make it out of the aircraft on July 31, 1944

Major Andrew S. Low, Jr. – Command Pilot

I was riding as command pilot for the first [time] with this crew. Believe it was 27th mission of most of crew. Left formation over the target after “Bombs Away”. All bailed out in target area, just (2 kilometers) north of Mannheim except two men, the top turret gunner and left waist gunner. Last saw Sgt Tharpe on flight deck going into bomb bays assisting Engineer in fighting fires. When alarm rang to bail out his chute opened in the airplane, burned and set him on fire. I last saw Sgt Koch go into bomb bays to put out the fires about five minutes before we bailed out. I believe he was overcome by flames or loss of oxygen and did not hear bail out signal. Flames from bomb bay burned two pilots in cockpit, so it was impossible to see into bomb bay. All were rounded up by soldiers and all ended up in civilian jail in northern Mannheim suburbs together. Spent couple of hours in jail and then were taken to Luftwaffe field to guard house. One man turned his ankles on landing and the pilot, Major (then Captain) Robert E. Lamb, 0-438667, and myself were burned quite badly.

Captain Robert E. Lamb – Pilot

We left formation just after the target. Ship was hit on target, Mannheim. Ship exploded after all crew bailed out after bombs away except two who were killed in the bomb bay. The aircraft blew up and I was blown out. Sgt Tharpe went down into the bomb bay to assist Sgt Koch fight the fire. The ship exploded around the Mannheim area and so far I have been unable to find out the location where the ship hit or the bodies. Sgt Koch (wounded in the leg by flak) went down in the bomb bay to fight the fire caused by flak damage, which occurred on the bomb run. Seeing we were lead PFF ship and he knew that the successful completion of the mission depended on us, Sgt Koch, without regard for his own life, and wounded besides, went down into a flaming bomb bay and fought the fire so we could complete the mission.

I recommended Sgt Koch for the Silver Star, but have not heard if his family received the award. However I believe him worthy of a much higher award and would like to see it given to his family. The bravery of this man cannot be too highly estimated.

1Lt Thomas F. Comi – DR Navigator

We left formation on a northerly heading from Ludwigshafen. I saw all but two of my crew members on the ground and all had bailed out of their respective stations. Members on the flight deck bailed out the top hatch because of fire in the bomb bay. I have no knowledge of the two missing members of my crew. I saw all members of my crew on the ground at Mannheim aerodrome except the two in question. Most of them were slightly injured. Mickey man and navigator claim that Sgt Tharpe popped his chute after getting out of turret. Regarding Sgt Koch, Mickey man claims he was hit in the leg by flak. He was last seen stuck in the top hatch by Major Low, who claims he threw someone with an A-2 jacket out the top hatch. Koch was the only one wearing an A-2 jacket. [Since the Germans found the bodies of both Sgt’s Koch and Tharpe inside the wreckage of the plane, this must have been another crew member assisted out by Major Low]

1Lt William B. Buchsbaum – Mickey Navigator

We were Wing Lead, and eleven crew, including myself, bailed out. Major Low and Capt Lamb and myself through the top escape hatch; R. Popper and H. Lodinger through the nose wheel doors; S/Sgt Cayford left waist; T/Sgt Miller right waist; S/Sgt M. Maurello [sic] and S/Sgt F. Koussa also went out the waist; I have no knowledge of T/Sgt L. Koch or S/Sgt M. Tharpe. The latter two were in the aircraft at the time of my departure, I believe their clothing was ablaze.

I do not believe Sgt Tharpe bailed out. He was trapped in the bomb bay while fighting fire. He entered the bomb bay to aid T/Sgt Koch. In leaving the top turret, he “popped” a chute which ignited, engulfing both men in flames. The German authorities informed us that the bodies of Koch and Tharpe were found in the plane wreckage. To my knowledge no member of our crew saw the bodies or an identification to substantiate the German claim. [I] believe Tharpe was burned to death as it was his chute that “popped”. Also when I left, both men seemed hopelessly engulfed in flames. Koch (wounded by flak in the legs) was [also] trapped in the bomb bay fighting the flames and he had called for assistance from Tharpe. At this time chute was “popped” spreading flame. Believe he perished in ship as his chute was also in bomb bay and he seemed hopelessly trapped.

2Lt Herman Lodinger – Bombardier

We were lead ship – dropped about 2,000 feet [when hit] about five miles NE of Mannheim, Germany. Pilot, command pilot, both navigators jumped from the top escape hatch. Tail gunner, waist gunners (2), co-pilot, radio operator jumped from waist windows and camera hatch. Pilotage navigator and myself jumped from the nose wheel doors. Both engineers went down with ship – Koch was in bomb bay, Tharpe on flight deck. Tharpe pulled his rip cord by accident and chute burned in ship. Koch was last seen trapped in bomb bay fighting fire. He asked for another fire extinguisher just before bail out order. He also stated that he was hit in the leg by flak. He couldn’t jump because his chest chute pack was on the flight deck and fire spread from bomb bay to there, preventing him from reaching it. According to German intelligence officers [both] bodies were found near wreckage, badly burned.