Crew 30 – Assigned 753rd Squadron – October 25, 1943

Completed Tour

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Pos | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1Lt | David S Manker | 0742090 | Pilot | Aug-44 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

| 2Lt | John M Jircitano | 0886994 | Co-pilot | 31-Jul-44 | POW | Trsf to 389th BG w/Lamb Crew |

| 2Lt | James R McQuaid | 0811709 | Navigator | 23-May-44 | UNK | Promoted to 1st Lieutenant |

| 1Lt | William P Wilson | 0736602 | Bombardier | Aug-44 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

| T/Sgt | Edward B Cox | 32575003 | Radio Operator | Aug-44 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

| T/Sgt | Robert E Crosby | 35539878 | Flight Engineer | Aug-44 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

| T/Sgt | Roy T Jerome | 16085539 | Gunner | 01-Apr-44 | UNK | Placed on Flight Status |

| Sgt | Magnus V McHargue | 34354603 | Gunner | 02-Apr-44 | DNB | Broken neck in fall down stairs |

| S/Sgt | Harold H Skinner, Jr | 35544413 | Armorer-Gunner | Sep-44 | CT | Orig Crew member Complete Tour |

| S/Sgt | John E Treadway | 39120032 | Armorer-Gunner | 01-Apr-44 | UNK | Placed on Flight Status |

Crew 30 trained at Tonopah, Nevada in late 1943. They flew the Southern Ferry Route to England in January 1944 along with the rest of the 458th Bombardment Group. While the group flew its first combat mission on March 2, 1944, Crew 30’s first mission came a little later than most crews in the group, on March 16, 1944. Their aircraft was shot up over Abbeville, France on the way back, but they managed to land more or less intact back at Horsham St. Faith.

On March 28, 1944, after flying six missions, 2Lt John Jircitano was transferred to the 389th Bombardment Group as co-pilot on 1Lt Robert Lamb’s lead Crew #20. They were shot down on July 31, 1944 while flying lead with Major Andrew Low from the 453rd Bomb Group, on a mission to Ludwigshafen, Germany. Two men from their crew were killed in the plane, but Jircitano and Lamb, along with nine others managed to bail out safely. They spent the rest of the war in German prison camps.

On April 2, 1944, while on leave in Norwich, S/Sgt Magnus McHargue was killed when he fell down a flight of stairs, breaking his neck. He was buried at the American military cemetery in Cambridge on April 6, 1944. His remains were returned home to Moultrie, Georgia at the request of his wife in May 1948. Taking his place, may have been S/Sgt William S. Dishner, whose name appears on two loading lists after April 1944.

Two members of Crew 30 were credited with confirmed enemy fighters destroyed, both in April 1944. On April 11th the group flew a mission to the JU-88 aircraft factory and airfield at Oschersleben, Germany. S/Sgt Robert Crosby shot down a fighter from the top turret. Two and a half weeks later, on April 29th the group flew a mission to Berlin to bomb Friedrichstrasse Station. Navigator 2Lt James McQuaid, manning the nose turret, was credited with one enemy fighter destroyed. Group records note the dates of these “victories”, but, unfortunately, no details.

While three crew members names do not appear in the records after May 1944, it is most likely that the entire completed their tour in August 1944. 1Lt David Manker was transferred at the end of August 1944 to a base in Southern England. From there he and other crews flew gasoline over to France, living in tents and mud. They flew these re-supply missions until the middle of December and then were returned to the States.

Missions

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

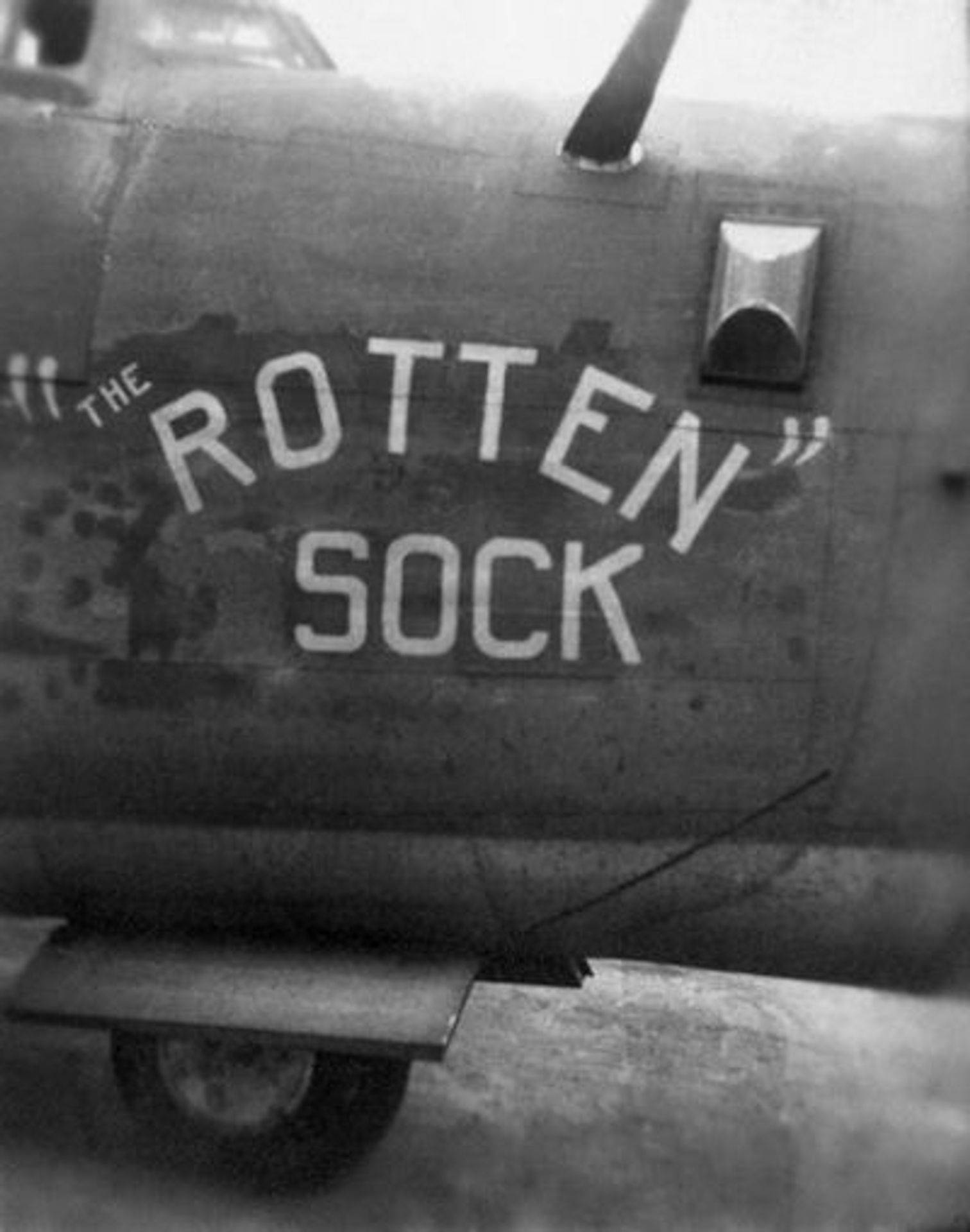

| 16-Mar-44 | FRIEDRICHSHAFEN | 8 | 1 | 41-29276 | T | J4 | 2 | The ROTTEN SOCK | CRASH LAND HORSHAM |

| 18-Mar-44 | FRIEDRICHSHAFEN | 9 | 2 | 41-29273 | Q | J4 | 6 | FLAK MAGNET | |

| 21-Mar-44 | WATTEN | 10 | 3 | 41-29273 | Q | J4 | 7 | FLAK MAGNET | |

| 22-Mar-44 | BERLIN | 11 | 4 | 41-28721 | L | J4 | -- | DOWNWIND LEG | ABORT - SORTIE CREDIT |

| 26-Mar-44 | BONNIERES | 14 | 5 | 41-28735 | S | J4 | 5 | UNKNOWN 005 | |

| 27-Mar-44 | BIARRITZ | 15 | 6 | 41-28735 | J4 | 6 | UNKNOWN 005 | ||

| 10-Apr-44 | BOURGES A/F | 19 | 7 | 41-29276 | T | J4 | 5 | The ROTTEN SOCK | |

| 11-Apr-44 | OSCHERSLEBEN | 20 | 8 | 41-29276 | T | J4 | 6 | The ROTTEN SOCK | |

| 13-Apr-44 | LECHFELD A/F | 21 | 9 | 41-29276 | T | J4 | 7 | The ROTTEN SOCK | |

| 18-Apr-44 | BRANDENBURG | 22 | 10 | 41-28733 | P | J4 | 15 | RHAPSODY IN JUNK | |

| 20-Apr-44 | SIRACOURT | 24 | 11 | 41-29276 | T | J4 | 9 | The ROTTEN SOCK | EMERG LANDING |

| 25-Apr-44 | MANNHEIM A/F | 27 | NTO | 41-28706 | F | J4 | -- | DREAM BOAT/SPARE PARTS | NO TAKE OFF -SUPER CHGR |

| 26-Apr-44 | PADERBORN A/F | 28 | 12 | 41-28706 | F | J4 | 12 | DREAM BOAT/SPARE PARTS | |

| 27-Apr-44 | BONNIERES | 29 | 13 | 42-50320 | J | J4 | 2 | UNKNOWN 018 | |

| 27-Apr-44 | BLAINVILLE-SUR-L'EAU | 30 | ABT | 42-109812 | D | 7V | -- | UNKNOWN 016 | ABORT - #3 ENGINE |

| 29-Apr-44 | BERLIN | 31 | 14 | 41-28706 | F | J4 | -- | DREAM BOAT/SPARE PARTS | ABORT - SORTIE CREDIT |

| 05-May-44 | SOTTEVAST | 35 | 15 | 41-28705 | H | J4 | 23 | YE OLDE HELLGATE | |

| 07-May-44 | OSNABRUCK | 36 | 16 | 41-28735 | S | J4 | 21 | UNKNOWN 005 | |

| 08-May-44 | BRUNSWICK | 37 | 17 | 41-28705 | H | J4 | 25 | YE OLDE HELLGATE | |

| 13-May-44 | TUTOW A/F | 41 | 18 | 42-95183 | O | J4 | 3 | BRINEY MARLIN | |

| 08-Jun-44 | UNSPECIFIED TGTS | AZ04 | -- | 44-40273 | T | J4 | -- | HOWLING BANSHEE | ABANDONED-WEATHER |

| 14-Jun-44 | 5 TARGETS | AZ06 | 19 | 44-40134 | R | J4 | 1 | UNKNOWN 039 | AZON MISSION |

| 15-Jun-44 | 3 RAILWAY BRIDGES | AZ07 | 20 | 44-40134 | R | J4 | 2 | UNKNOWN 039 | AZON MISSION |

| 24-Jun-44 | CONCHES A/F | 78 | 21 | 42-50320 | W | J3 | 23 | UNKNOWN 018 | MSN #3 |

| 29-Jun-44 | ASCHERSLEBEN | 82 | 22 | 42-95183 | U | J3 | 16 | BRINEY MARLIN | |

| 12-Jul-44 | MUNICH | 89 | 23 | 42-110163 | M | J4 | 7 | TIME'S A WASTIN | |

| 19-Jul-44 | KEMPTEN | 94 | 24 | 42-100431 | B | J4 | 28 | BOMB-AH-DEAR | |

| 20-Jul-44 | EISENACH | 95 | 25 | 44-40281 | Q | J4 | 6 | A DOG'S LIFE | |

| 21-Jul-44 | MUNICH | 96 | 26 | 44-40285 | H | J4 | 14 | TABLE STUFF | |

| 28-Jul-44 | LEIPHEIM & CREEL | SCR | -- | 44-40201 | N | J4 | -- | SILVER CHIEF | BRIEFED AND SCRUBBED |

| 31-Jul-44 | LUDWIGSHAFEN | 99 | 27 | 42-110141 | U | J4 | 6 | BREEZY LADY / MARIE / SUPERMAN | |

| 02-Aug-44 | 3 NO BALLS | 101 | 28 | 44-40134 | R | J4 | 10 | UNKNOWN 039 | *LDF |

| 09-Aug-44 | SAARBRUCKEN | 109 | 29 | 42-110141 | U | J4 | 13 | BREEZY LADY / MARIE / SUPERMAN | |

| 13-Aug-44 | LIEUREY | 112 | 30 | 44-40275 | L | J4 | 11 | SHACK TIME | |

| 14-Aug-44 | DOLE/TAVAUX | 113 | 31 | 42-110141 | U | J4 | 14 | BREEZY LADY / MARIE / SUPERMAN |

Crew 30 in England

Front Row: David Manker, William Wilson, James McQuaid, John Jircitano

(Photo: David Manker)

David Manker’s WWII Recollections

In early 1942, I was enrolled in a C.P.T. (Civilian Pilot Training) program at Lovell Field in Chattanooga. Fortunately, I was in the top 10% in ground school grades that qualified me for 35 hours flying time and a private pilot’s license, with the stipulation that we had to enlist in the Army or Navy Air Corps. I chose the Army Air Corps.

I received notification to board a special train in Chattanooga in early July. The train departed from Maine and traveled through Chattanooga, Chicago, and across the country to Santa Ana, California. Two C.P.T. training pilots were picked up in various cities across the country. The last two boarded in Los Angeles making a total of about 350 pilots in the group.

From pre-flight camp in Santa Ana, I was sent to Ontario, California for primary training in a Stearman plane; and from there to Merced, California for basic training in the BT-13. Bad weather forced our relocation to Palmdale, California for a month in the desert. From Merced, I went to Stockton, California for advanced training in AT-9 and AT-17 twin engine planes.

After getting a 2nd Lieutenant commission and wings in April 1943, I was sent to Mather Field in Sacramento, California to train in B-25s. Our group was split in half after three months. One half went to the South Pacific as co-pilots on B-25s. My half was sent to Hobbs, New Mexico to fly B-17s. At the end of August, we were given a 10-day furlough, and I spent five days of it at home in Chattanooga.

Our group was then transferred to Gowan Field in Boise, Idaho for training on the B-24. Two months later, I was sent to Tonopah, Nevada for more B-24 training. Our crew of ten members was formed there. I have always felt blessed that I had nine outstanding crew members. I have stayed in touch with them since WWII ended. In December 1943, we were given a new B-24 and sent to San Francisco. Two weeks later we flew to West Palm Beach for three days, and from there in late December to South America, Africa, and England.

We started combat flying in January 1944 out of Horsham St. Faith Air Base outside of Norwich, England. Our first mission was to Munich, Germany and my crew flew 31 missions over France and Germany. Following are stories of some of the more memorable missions.

First Mission to Friedrichshafen

Near Munich: On our first mission we attempted to drop our fifty 100-lb. incendiaries on Munich, but they would not drop. The engineer or radio operator pulled the salvo lever by my seat, and they still wouldn’t drop. We had a big problem: we were afraid we would not have enough fuel to make it back to England carrying the 5,000-lb. load. At Abbeville, France we were hit by a lot of flak. Some of it punctured a wing tank, and gas was leaking into the bomb bay. The radio operator or engineer pulled on the salvo lever again, and he pulled so hard that the lever and its attached metal cable came completely out.

This time the bombs dropped – right through the bomb bay door! Now we really had to worry about losing what little gas we had left.

We made it to our air base and landed with a blown-out tire making sparks fly off of the metal rim. We ran off the runway onto the grass where the plane stopped. Our engineer/top turret gunner, Bob Crosby, climbed onto the wings and he told me that he could see no gas in any of the tanks. We had used up all 2,700 gallons. We counted 67 flak holes in our plane. I still believe that God had a hand in our making it back that day – and all other days.

Berlin #1

We lost an engine about an hour before we reached Berlin on another mission. We dropped out of formation and headed back to England. En route, we dropped our bombs on a target of opportunity (railroad tracks in Germany). Shortly after we started back, a P-38 with one engine out joined up with us. His wingman, who still had two fans running, stayed along with us, and we safely made it back.

Berlin #2

On another mission to Berlin, I lost a supercharger and could not keep in formation. Again we turned back toward England about an hour before Berlin; and again we dropped our bombs on a target of opportunity (railroad track). We had to decide at what altitude to fly. German fighters loved to catch a bomber alone and shoot it down. I wanted to be below the German radar where they couldn’t pick us up. I took a chance and dropped down to about 100 to 200 feet above the ground and hoped that we wouldn’t fly over or near a German fighter base. We stayed at that altitude all the way to England where we landed safely.

“Milk Run” – 11th Mission [April 20, 1944]

Our 11th mission was a “milk run” to the Paris area. A doctor friend had told me that if I ever got a short “milk run”, he would like to go with us to see what it was like “up there”. I told him he could go with us on this mission if he would get permission from someone much higher up. He did, and rode in the waist. I told crew members to fit him in a parachute and instruct him how to use it. [According to Suffolk Police and Civil Defense reports recently acquired from Mr. Philip Baldcock, the officer was 1Lt Charles R. Carter, who is listed in 458th records as 753rd Squadron Adjutant.]

The Rotten Sock, April 20, 1944: RAF personnel, Unknown, Unknown, William Wilson, Leland Griffith, David Manker, Bob Crosby, Ed Cox

Just as we crossed the French coast, flak blew my right rudder off leaving us with no control except aileron for up, down and turning. When the flak hit the rudder, it did not immediately break completely off, but set up a terrible vibration on the rudder pedals. After about a minute, it broke off. We dropped our bombs in the English Channel and went down to 4,000 feet over England. I knew I would land at the first airport I saw. I called the crew and told them we might crash on landing and if anyone wanted to bail out to go ahead. My tail gunner [S/Sgt John E. Treadway] had always wanted to make a parachute jump. He, a waist gunner [Sgt William L. Zottoli], and the doctor [1Lt Charles E. Carter] jumped. It was the doctor’s last mission! I contacted a British air base I spotted and went in for a landing. We made it down alright, but we missed the runway and landed on the grass. Our base sent a plane to pick us up. All three men who parachuted also returned to base. My co-pilot this day was Lt. Griffith, a fine man. He was killed in a crash in September 1944.

Suffolk Police Report

April 20th 1944 at 19.30 Three airman baled out. One landed at Stonegate, believed injured to Kent & Sussex Hospital by Burwash ambulance. Two others baled out unhurt Ticehurst. (The Police records, note the following:) Three members of an American Liberator bomber and landed in the Ticehurst area, including three legged Cross. The aircraft had been seen flying south to north at 2,000 feet. The number of the aircraft being K.T.J.A (*see note below). Staff Sergeant 39120032 John Eugene Treadway, landed at Myskyns. He was unhurt and taken by PC Latter to Cottenden, the residence of Captain Bramall. The officer then attended to 11050362 William L Zottoli who landed at Shoyeswell, Ticehurst. This man was injured and unable to move. PC Latter summoned medical attention and Doctor East of Ticehurst and the Burwash ARP ambulance attended. The constable then went to the searchlight unit at The Cross, Ticehurst and was informed that 1st Lieutenant C E Carter [sic] had landed at Burnt Lodge, Ticehurst and had later been moved to Staplehurst aerodrome. The pilot had ordered the men to bale out as a precaution, presumably the aircraft had been damaged, but it seems to have made base safely. The injured man was taken to the K&S Hospital.

(*) There is an apparent contradiction as to whether the injured crew member landed at Ticehurst or Stonegate but the police report is probably correct. The aircraft number of K T J A in fact relates to the 458th Bomb Group. K being the group’s tail letter; T is the individual aircraft code letter and J4 (not JA), refers to the 753rd Bomb Squadron. In the Police report, S/Sgt Treadway’s first Christian name of John is left out. The 458th BG was based in Norfolk at Horsham St Faith, now Norwich Airport.

Courtesy: Philip Baldcock

ME-109

We were in tight formation at 20,000 feet on one mission, and a German ME-109 fighter pilot misjudged his speed and failed to abort his attack. He was caught inside our formation on the left of my plane. One of our planes on his left was slightly up and ahead of him. No gunners could shoot at him without hitting our own planes. He stayed in that position for several minutes. Suddenly, he cut power, dropped down, and rolled over on his back. Numerous guns fired at him and his plane exploded. I have often thought that he could have rammed the wing of the B-24 ahead of me and taken it with him.

Co-pilots

Our co-pilot was John Jircitano. On one of our early missions, I looked over at Jircitano, and he had gone to sleep. I called the radio operator to come wake him up. Cox found out that his oxygen line had come loose and he was unconscious. I really wondered had I not noticed him if he might have expired. Jircitano was transferred to the 389th Bomb Group [with Robert Lamb’s crew] about the time we had finished our seventh mission. They were shot down in July.

After that, I had several different co-pilots, one of whom was John Luft from Crew 25. He was an excellent co-pilot. On one mission they gave me a new first pilot to fly as co-pilot. His name was McCarthy. He was from New York City, and I believe he had been a policeman. It was not unusual for a new pilot to fly co-pilot on his first time out.

If you saw a fighter plane coming towards you and it looked as if its landing lights were blinking, you could be sure it was a German plane. The “landing lights” were his guns firing! On this particular mission with McCarthy, we saw a fighter coming towards us from three o’clock level. It was the new ME-262 jet plane. He was firing and then broke off the attack. McCarthy shouted, “He missed us!” Cox, our radio operator, was standing between the seats and said, “Lieutenant, look just below your seat on the right side.” There was a hole about one inch in diameter. The bullet had gone out on my side.

A B-24 goes down

We were in formation at 20,000 feet. A B-24 was directly in front of me, but up a couple of hundred feet. He took a direct flak hit in the center of the plane. Smoke came out of the waist windows. One man bailed out, and I thought he was going to hit my props as he fell in front of me. He passed right before me and I saw that he was not wearing a parachute. Just as he passed me his plane exploded and fell in a thousand parts. In a few second, there was just an empty space there in the formation.

D-Day

I was awakened at 2:00 A.M. on D-Day rather than as usual at 3:30 A.M. I was told that no one else from my crew was wanted – just me. At the 3:30 A.M. briefing we were told we would be [going] on a mission to the Normandy invasion [area]. I was to fly co-pilot to a Lt. Colonel in the Spotted Ape [assembly] airplane. This plane had blinking lights and big white spots on it and was used for the group to form on at about 15,000 feet. After the group was together, we left and returned to the base. As we were approaching the English Channel, I looked down and saw so many boats of all kinds that I felt as if I could have walked across the Channel on the boats.

The men going ashore had been told that any aircraft overhead that day would be ours and that no Germans would be in the sky. That was correct. Bombers hit the shore just before the invasion and our fighters controlled the sky.

AZON bombing:

We went on a couple of these short, experimental missions into France. The bombardier could guide the bomb left or right through radio control. On one of the two missions, our target was a bridge. The bomb was headed off course toward a big building, but the bombardier was able to direct it away from the building. We learned later that the building was a German headquarters!

Lt. David S. Manker and B-24J 44-40283, an original AZON ship

My two most embarrassing moments

Several pilots were sitting around the barracks talking. They started pulling out family pictures. One of them handed me a picture of a woman and I said, “This is a good picture. Is this your mother?” He said, “NO! It’s my wife!”

In England, I was in the mess hall when a pilot I knew came up to me and said, “Hello, did you miss me?” I said, “No. Where have you been?” He said, “I got shot down six weeks ago and the French underground walked me over the Pyrenees Mountains into Spain. Now I’m back here.”

The Hand of Fate

There were 16 crews in my squadron when we went over and 8 crews came back. My good friend, George Spaven, a pilot who roomed with me, was killed on a raid to Hamm, Germany. I did not fly that day. I was told that most of his crew was seen bailing out. When the airplane was last seen, it was still flying. I had hoped that George was able to get out of the plane before it went down, but I was told later that he had been killed. Another day a pilot asked me to take his plane and crew on a mission, and he would do the same for me later on. I declined. He was shot down that day. I have often wished that I had kept a diary of my combat time.

Flying gas for Patton

I completed 31 missions in August 1944, and I was ordered to go home “tomorrow”. At 10:00 P.M., I was told that I was not going home. They sent Chuck Shaw [pilot, Crew 26] and me to southern England. We met up with approximately 40 other pilots, and we were given new B-24’s. They loaded the bomb bay with 5-gallon cans of gasoline and we flew them to a fighter base near the front lines where the cans were unloaded and most of the gas was taken out of our wing tanks. This gasoline went to General Patton for his tanks. We spent the night and flew back to our nice, comfortable base in England.

I went on a flight hauling gas where we flew at about 2,000 feet. We were a flying bomb with all the gas on board, but no one was shooting at us. I lost an engine on the way in, and we were landing it at a P-47 fighter base that day on a steel mat for a runway. I left the plane, and rode back with Shaw. They gave me another new plane. I was back at the base a couple of weeks later and was told that the major had gotten the engine fixed and now had his own private B-24. I don’t believe a word of that, as he would have surely killed himself trying to fly a four-engine plane.

While flying gas, I landed in Paris three days after it was liberated. I got into Paris in the late afternoon. The street running from the Arc de Triomphe to the Eiffel Tower was filled with jubilant people celebrating their freedom from the Germans. Drinks were on the house at the bars for us. We had our pistols on our belts as we were told some German snipers were still active in the area. I spent the night as the gas was unloaded. I returned to Paris three times later in civilian life. It was the most beautiful city I had ever seen. It was so good that the Germans did not burn it down as Hitler had ordered them to.

One afternoon, we landed in Brussels, Belgium. We went to town looking for a place to get some food. We saw a small restaurant and went in. It would seat about fifteen people. The owner spoke English very well. We asked if he could fix us some food. He said that he was sorry, but the only thing he could offer us was a steak and baked potato. We had not had a steak in three months!

At some point around November, some high-ranking officer decided to move all of us to a captured airfield near Chartres, France. We had to move into tents with wood-burning heaters. Mud was everywhere. There were neither showers nor running water. The plan called for us to fly empty to England to get the gas, then fly to the front lines and unload, and then fly back to our tents. Wasn’t that a stroke of genius on somebody’s part? We spent the Battle of the Bulge in Tent City where we could not get off the ground for over two weeks because of bad weather. It was COLD. We really felt for the GIs in the ground war. I had 13 English cotton blankets for my cot and still couldn’t get warm.

One of the pilots found a place in Chartres where he bought a bunch of paintings. He sold four of them to me and they are framed on our walls.

We needed firewood. Someone discovered that we could get three or four trucks and some German prisoners and have them cut wood for us. There were about four prisoners and two of us officers with loaded rifles on each truck. The prisoners could have easily overpowered us, but I believe they were glad to have been captured. While they were chopping wood, I foolishly decided to fire my rifle into the air. I mean – I got everyone’s attention.

I heard, about after three weeks, there was a public shower in Chartres, but no hot water. I took the coldest bath of my life, but it was worth it.

This outfit was put together about September, and all of us went home the last of December. Some time in November, Chuck Shaw talked the commanding officer into letting the two of us take a plane and fly back to Norwich, England to get our mail. We got to Norwich where Chuck knew one of the crew chiefs real well. The crew chief agreed we had a bad tire on our plane that had to be replaced. So, we spent the night there. The next day, the crew chief agreed the other tire looked bad also and needed to be replaced. So, we spent a second night there. I got to go to see the pretty little English girl I had dated the whole time I was in Norwich.

Margie came out to the air base twice to a Saturday night dance at the Officer’s Club. She wore a pink evening dress to the first dance, and a blue one the second time. We arranged for a cab to bring her to the base, and then pick her up at the end of the dance and take her home.

Half of the town of Norwich was bombed out. The other half was untouched. I remember a nice restaurant on the second floor of a building. Marge and I ate there often. They had one picture show. The only hotel was three stories, white and named the Bell Hotel. At the top of a hill, about five blocks up from town was a beautiful church. I wish I had gone in it and perhaps attended a service there. The town had one nice dance hall also. Taxicabs were 1937 Fords.

When Chuck and I were about to take off for France, two nurses asked us where we were headed. We told them, and they said they needed to get to Paris. So we dropped them off in Paris and flew on to Chartres.

Aunt Margaret’s favorite war story was of my going to the 5-hole potting [toilet] on our base in France. I went in, and a pilot was sitting on the #5 hole. I sat down on the #1 hole. In about one minute, the door opened and a French Red Cross girl came in and sat on the #3 hole. All I knew was that she was going to leave before I did! A minute or so passed, and she hopped up and went out.

I was given a new .45 caliber pistol still in the box it was shipped in. I really wanted to bring it home, but we were told that if we were caught with such items, our return would be delayed a good while. I gave it away.

Home again

In December 1944, I was sent back to England. I then came back to the States on a converted luxury liner. I spent Christmas Day 1944 on the ocean. The ship had 5,000 amputees on it. We able-bodied personnel were required to stand watch on 6-hour shifts, 24 hours a day in all compartments. These men smoked, and if a fire started they could not get out. Plus, we were to see if everyone was okay. It was a pleasure to do that for them.

After returning home, I had 30 days leave with my family in Chattanooga. Afterwards I was sent to Miami for reassignment. I was given two choices: be an instructor or go to the South Pacific. I chose to be an instructor. When asked where I would like to instruct, I chose Smyrna Air Base near Nashville, Tennessee. I was there from February 1945 until I was discharged in August of that year. I was given an intensive training course in flying the B-24, which I should have had before going overseas – not afterwards.

I got my first student pilots in July and then I was out in August. My roommate at Smyrna was a pilot who was with me in Europe. He was killed in a mid-air collision near Nashville in June.

After discharge, I worked for a few months then enrolled at Vanderbilt and also was married at the end of my first quarter. Some people question me when I say that I graduated from high school in 1939 and from college in 1949. I just tell them that I am a slow learner.

1Lt David S. Manker, Chattanooga, January 1945 (Photo: David Manker)