Boucek Crew – Assigned 753rd Squadron – August 25, 1944

Standing, 2nd left: William Boucek – P

Kneeling, 2nd left: Robert Schopp – RO

Completed Tour

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Crew Position | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1Lt | William C Boucek | 0823291 | Pilot | 23-Mar-45 | CT | Trsf to 356FG at own request |

| 1Lt | Edward V Day | 0755527 | Co-pilot | 26-Mar-45 | CT | Trsf to 70th CP - Completed Tour |

| 1Lt | Leslie B Williams | 0722408 | Navigator | 19-Apr-45 | CT | TD to RAF Bomber Devel Unit |

| 1Lt | Clifford W Bransdor | 0717739 | Bombardier | 10-Feb-45 | CT | Trsfr to 755th Sqdn |

| T/Sgt | Robert G Schopp | 36746410 | Radio Operator | 26-Mar-45 | CT | Trsf to 70th CP - Completed Tour |

| T/Sgt | Charles W VanFleet | 17060632 | Flight Engineer | 26-Mar-45 | CT | Trsf to 70th CP - Completed Tour |

| S/Sgt | Robert A Carrozza | 13132070 | Armorer-Gunner/2E | 25-Feb-45 | CT | Mission Load List - Bowers Crew |

| S/Sgt | Loyd F Mulsow | 37726473 | Aerial Gunner | 26-Mar-45 | CT | Trsf to 70th CP - Completed Tour |

| S/Sgt | George E Thompson | 36465383 | Armorer-Gunner | 26-Mar-45 | CT | Trsf to 70th CP - Completed Tour |

| S/Sgt | James L Nearhoof | 33573939 | Aerial Gunner | 10-Apr-45 | CT | Reclassified MOS 938 Gunnery Inst |

The Boucek crew arrived at Horsham in the late summer of 1944, just in time to participate in the Truckin’ runs in September. The crew flew on eight of these missions, bringing gasoline to Patton’s Third Army in France. Their first combat mission was on October 7th to Magdeburg. Boucek recorded 35 missions between October 1944 and March 1945. While the crew returned to base without dropping any bombs on the mission of February 8, 1944 due to a Recall, they would not abort one single mission during their entire tour – a rare occurrence for 35 trips over the Continent.

Most of the crew probably finished heir missions with Boucek, save for two. Lt Clifford Bransdor, the crews bombardier, was transferred to the 755th Lead Squadron in mid-February, but it is not know with whom or how many lead missions he flew. S/Sgt Robert Carroza, a gunner on the crew, was also rated as a Flight Engineer. He was transferred to the 755th Squadron in November and is shown on at least one load list on the crew of Lt Waldo Bowers. It is not known when he completed his missions.

Lt William Boucek, after “driving” a B-24 Liberator around the skies of Europe for seven months, volunteered for combat duty as a fighter pilot. He was sent to the 360th Squadron in the 356th Fighter Group, flying P-51 Mustangs out of Martlesham Heath in Suffolk. He was able to get in two combat missions before the war ended, but the details of these flights are unknown. Tragically, on June 30, 1945 while on a “test hop”, his P-51 came hurtling out of the clouds minus its left wing. While Boucek did manage to get out, his chute either failed or he was too low for it to open.

Lt Clifford Bransdor survived the war and stayed in the Air Force. While on a flight from the Azores to Rapid City, South Dakota, he was killed in an accident on March 18, 1953. He was the Electronic Countermeasures Officer on board a B-36 Peacemaker when it crashed into a hilltop in Newfoundland. None of the 23 crew members survived.

Missions

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21-Sep-44 | HSF to LILLE | TR05 | -- | 42-52455 | O | J4 | T3 | PLUTOCRAT | CARGO |

| 22-Sep-44 | HSF to LILLE | TR06 | -- | 41-28719 | Q | J3 | T4 | PADDLEFOOT | NOT ON OPS 5-OCT-44 LIST |

| 25-Sep-44 | HSF to LILLE | TR08-1 | -- | 41-28721 | G | J4 | T5 | DOWNWIND-LEG | 1ST FLIGHT - WW |

| 25-Sep-44 | HSF to LILLE | TR08-2 | -- | 41-28682 | I | 754 | T6 | NO NAME or NAME UNKNOWN | 2ND FLIGHT - WW |

| 26-Sep-44 | HSF to LILLE | TR09 | -- | 42-7629 | A | 755 | T6 | NOT 458TH SHIP | TRUCKIN' MISSION |

| 28-Sep-44 | HSF to LILLE | TR11 | -- | 41-28705 | X | 753 | T6 | YE OLDE HELLGATE | TRUCKIN' MISSION |

| 29-Sep-44 | HSF to LILLE | TR12 | -- | 41-28705 | X | 753 | T8 | YE OLDE HELLGATE | TRUCKIN' MISSION |

| 30-Sep-44 | HSF to LILLE | TR13 | -- | 41-28705 | X | 753 | T9 | YE OLDE HELLGATE | TRUCKIN' MISSION |

| 07-Oct-44 | MAGDEBURG | 130 | 1 | 44-40118 | S | J4 | 9 | WE'LL GET BY | |

| 09-Oct-44 | KOBLENZ | 131 | 2 | 42-50449 | W | J4 | 2 | HEAVENLY HIDEAWAY | |

| 15-Oct-44 | MONHEIM | 134 | 3 | 41-29596 | R | Z5 | 60 | HELL'S ANGEL'S | SPARE |

| 17-Oct-44 | COLOGNE | 135 | 4 | 42-50449 | W | J4 | 5 | HEAVENLY HIDEAWAY | |

| 22-Oct-44 | HAMM | 137 | 5 | 42-50449 | W | J4 | 7 | HEAVENLY HIDEAWAY | |

| 30-Oct-44 | HARBURG | 139 | 6 | 44-40277 | P | J4 | 18 | MISS USED | |

| 02-Nov-44 | BIELEFELD | 140 | 7 | 42-50449 | W | J4 | 10 | HEAVENLY HIDEAWAY | |

| 04-Nov-44 | MISBURG | 141 | 8 | 44-40118 | S | J4 | 12 | WE'LL GET BY | |

| 16-Nov-44 | ESCHWEILER | 147 | 9 | 42-50449 | W | J4 | 16 | HEAVENLY HIDEAWAY | WRITTEN IN PENCIL |

| 26-Nov-44 | BIELEFELD | 150 | 10 | 42-50449 | W | J4 | 19 | HEAVENLY HIDEAWAY | |

| 06-Dec-44 | BIELEFELD | 153 | 11 | 42-50449 | W | J4 | 20 | HEAVENLY HIDEAWAY | |

| 12-Dec-44 | HANAU | 156 | 12 | 42-50449 | W | J4 | 22 | HEAVENLY HIDEAWAY | |

| 25-Dec-44 | PRONSFELD | 158 | 13 | 42-50449 | W | J4 | 24 | HEAVENLY HIDEAWAY | |

| 27-Dec-44 | NEUNKIRCHEN | 159 | ASSY | 41-28697 | Z | Z5 | A39 | SPOTTED APE | ASSEMBLY CREW - 752ND |

| 28-Dec-44 | ST. WENDEL | 160 | 14 | 42-50449 | W | J4 | 26 | HEAVENLY HIDEAWAY | |

| 31-Dec-44 | KOBLENZ | 162 | 15 | 42-50449 | W | J4 | 28 | HEAVENLY HIDEAWAY | |

| 01-Jan-45 | KOBLENZ | 163 | 16 | 42-50449 | W | J4 | 29 | HEAVENLY HIDEAWAY | |

| 07-Jan-45 | RASTATT | 166 | 17 | 42-50449 | W | J4 | 31 | HEAVENLY HIDEAWAY | |

| 29-Jan-45 | MUNSTER | 175 | 18 | 44-40134 | R | J4 | 45 | UNKNOWN 039 | |

| 31-Jan-45 | BRUNSWICK | 176 | MSHL | -- | -- | -- | -- | MARSHALING CHIEF- 753RD | |

| 03-Feb-45 | MAGDEBURG | 177 | 19 | 42-50449 | W | J4 | 38 | HEAVENLY HIDEAWAY | |

| 06-Feb-45 | MAGDEBURG | 178 | 20 | 42-50449 | W | J4 | 39 | HEAVENLY HIDEAWAY | |

| 08-Feb-45 | RHEINE M/Y | REC | -- | 42-50449 | W | J4 | -- | HEAVENLY HIDEAWAY | RECALL - WEATHER |

| 09-Feb-45 | MAGDEBURG | 179 | 21 | 42-50449 | W | J4 | 40 | HEAVENLY HIDEAWAY | |

| 14-Feb-45 | MAGDEBURG | 181 | 22 | 42-50449 | W | J4 | 42 | HEAVENLY HIDEAWAY | |

| 16-Feb-45 | OSNABRUCK | 183 | 23 | 44-40285 | H | J4 | 61 | TABLE STUFF | 449W SCRATCHED OUT |

| 22-Feb-45 | PEINE-HILDESHEIM | 186 | 24 | 42-50449 | W | J4 | 46 | HEAVENLY HIDEAWAY | |

| 24-Feb-45 | BIELEFELD | 188 | 25 | 44-40118 | S | J4 | 40 | WE'LL GET BY | |

| 25-Feb-45 | SCHWABISCH-HALL | 189 | 26 | 44-40273 | T | J4 | 39 | HOWLING BANSHEE | LANDED A-74 - FUEL |

| 27-Feb-45 | HALLE | 191 | 27 | 44-40273 | T | J4 | 40 | HOWLING BANSHEE | |

| 28-Feb-45 | BIELEFELD | 192 | 28 | 44-40273 | T | J4 | 41 | HOWLING BANSHEE | |

| 02-Mar-45 | MAGDEBURG | 194 | 29 | 44-40273 | T | J4 | 43 | HOWLING BANSHEE | |

| 03-Mar-45 | NIENBURG | 195 | 30 | 42-95183 | U | Z5 | 83 | BRINEY MARLIN | REPLACED 273 |

| 05-Mar-45 | HARBURG | 197 | 31 | 44-40273 | T | J4 | 45 | HOWLING BANSHEE | |

| 07-Mar-45 | SOEST | 198 | 32 | 44-40273 | T | J4 | 46 | HOWLING BANSHEE | |

| 09-Mar-45 | OSNABRUCK | 200 | 33 | 44-40273 | T | J4 | 47 | HOWLING BANSHEE | |

| 14-Mar-45 | HOLZWICKEDE | 203 | ACC | 44-40273 | T | J4 | -- | HOWLING BANSHEE | DMG IN GRND EXPLOSION |

| 15-Mar-45 | ZOSSEN | 204 | 35 | 42-110163 | M | J4 | 71 | TIME'S A WASTIN | LOST #4 ENG - SORTIE |

Horsham St Faith

William Boucek and Cliff Bransdor

Briefing Room

1. William Boucek, 2. Edward Day, 3. Leslie Williams

(Photos: Dave Bransdor)

356th Fighter Group

Pilots of the 360th Fighter Squadron

Lt’s John Sranick, William Boucek, Lawrence Proctor, and Robert Schmalz

June 30, 1945 – Accident Report 45-6-30-516

Click for AAF Form 14

DESCRIPTION OF ACCIDENT

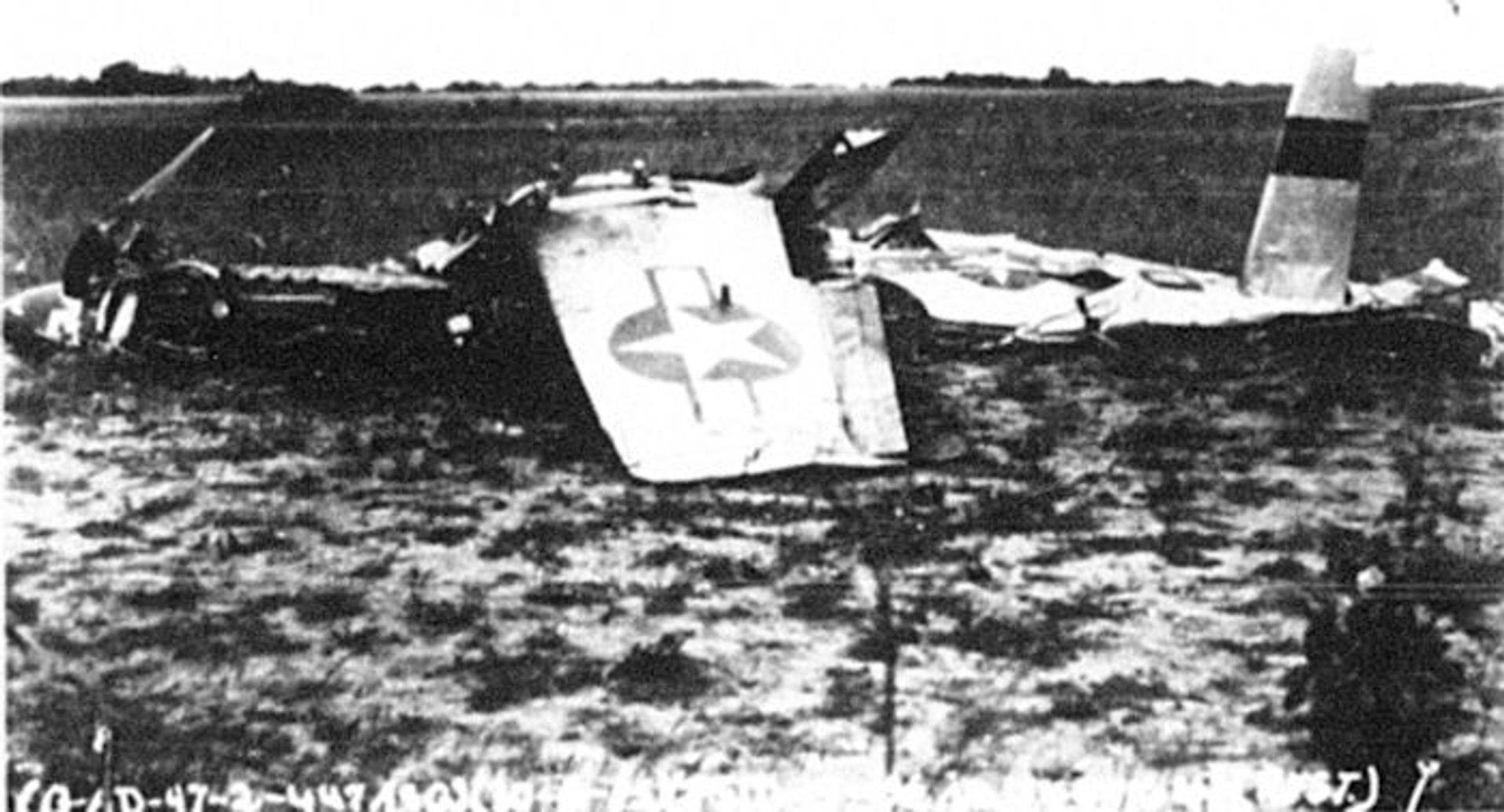

1. General At 0948 hours on 30 June 1945, 1st Lt William C. Boucek, 0823291, took off from home base (AAF station 369) on a local clearance for the purpose of testing his aircraft prior to ferrying it to the Continent. At approximately 1037 hours the Flying Control Officer at RAF Station Bentwaters heard the roar of an aircraft engine. About one minute later a P-51 came through the clouds with one wing missing and bits of debris following it, and crashed on the airfield. It is believed that the pilot got out at about 300-400 feet. Although the ripcord handle had been pulled, it is believed the chute did not open until impact with the ground.

2. The statement of the Flying Control Officer at RAF Station Bentwaters that the starboard wing was missing is erroneous. The left wing was missing, having been torn from the aircraft approximately 12” from where the wings are bolted together. The left wing was found approximately three miles from the aircraft. Witnesses who observed the wing falling through the air, state that the wheel was extended. The right wheel was still intact and in the retracted position in the right wing which was still attached to the fuselage.

3. Findings Examination of the left wing and wheel assembly revealed the following points of interest:

a. Although the left wheel and strut was actually broken from the landing gear casting, and were found underneath and slightly to the rear side of the wing, the half of the collar housing the upper end of the landing gear strut still fastened to the landing gear casting assembly was in the vertical position and he down-locking pin was engaged, proving conclusively that the wheel was in the down and locked position.

b. The wheel extended in spite of the hydraulic cylinder and plunger being in the “retract” position, by breakage of the linkage between the hydraulic plunger and wheel retracting casting. The pressure exerted to break this linkage caused by the wheel extending in spite of hydraulic system being in “retract” position, would have been very considerable. The weight of the wheel assembly by itself could not have done it, but would have to be aided and abetted by :G’s” or air pressure, or a combination of both.

c. The hydraulic cylinder which actuates the landing gear up and down, was in the full up or retract position, plunger fully extended.

d. Examination of the mechanical “locking-up” devices, which are part of the fuselage rather than the wing, appeared to be intact for both wheels. (See para. 3, i, for details).

e. That portion of the wing, which houses and covers the landing gear and strut cell, was torn away completely (from the inboard gun, back to the main spar, and thence inboard towards the fuselage to where the wing had sheared from the aircraft), and has never been found. Study of this section indicates that it was blown up and out by terrific air pressure from underneath.

f. The left wing flap was gone and has never been found.

g. The bulkhead at #75 station (divides gun compartments from ammunition bays, and probably the wings weakest station) was buckled slightly, and the rivets on the bottom of the wing, along with this station were “popped” out for a distance of some 8 -10”, starting from the trailing edge of the wing.

h. The wheel fairing door (for left wheel) was torn off and has never been found.

i. The landing gear up-lock device (for left wheel), upon removal from aircraft for examination, showed markings which prove conclusively that the pin on the wheel was allowed to slip out, even though the locking device was in the locked position. This was caused by the wing apparently flexing upwards enough to cause the wheel locking pin to be pulled outwards sufficiently to escape the locking device.

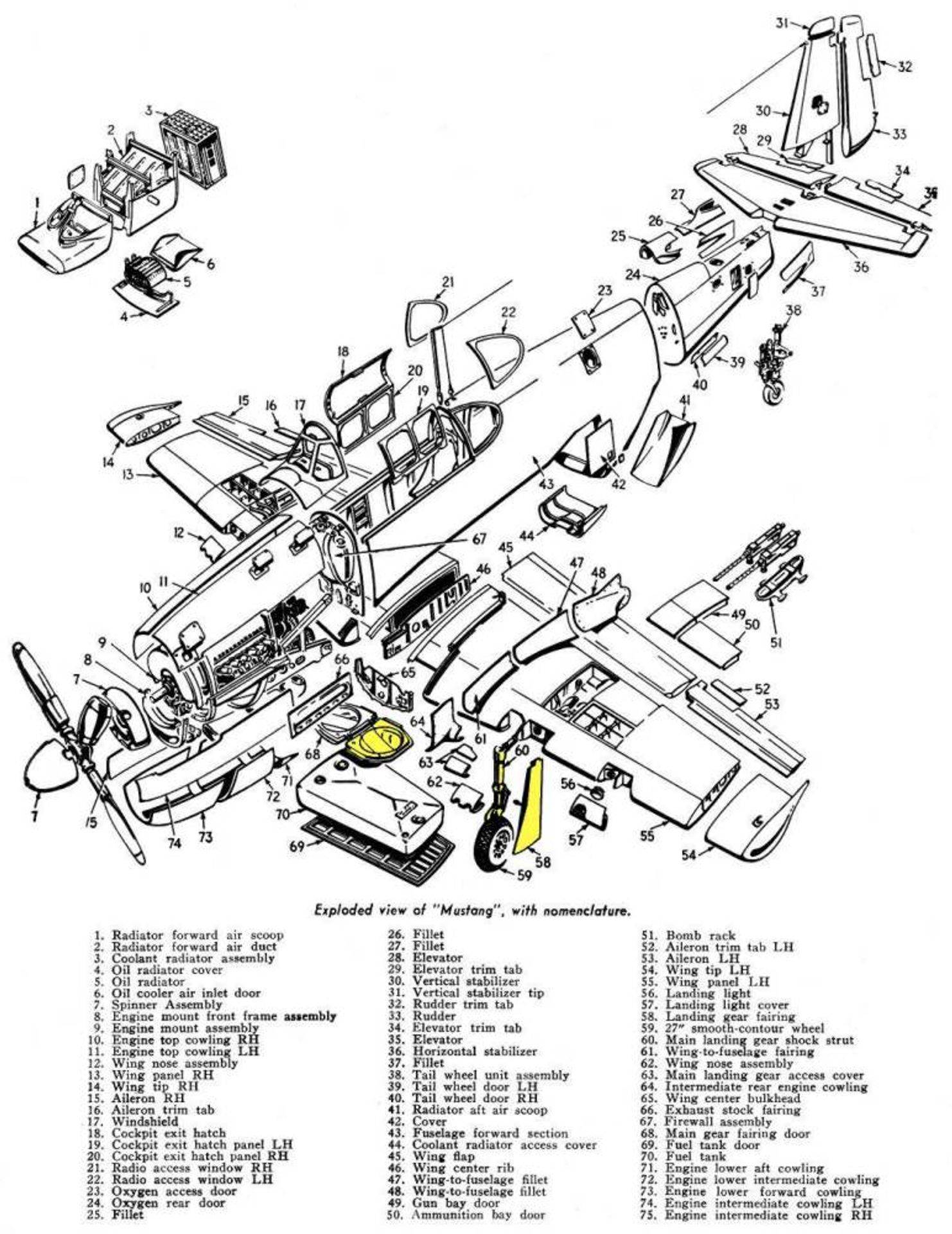

4. Analysis This accident presents two possibilities. [Diagram at left may help understanding of where some of the components listed below are located. Click diagram for a larger image]

a. Material failure at #75 station, caused by either metal fatigue, excessive speed, excessive “G’s”, or combination of all or any of above, causing wing to flex upwards sufficiently to allow up-lock pin to escape from its lock, and strut fairing to escape from over-lap of fairing door, allowing in turn the wheel to start extending. Terrific air pressure captured in wheel well, coupled with possible positive “G’s”, extended the wheel against the hydraulic system’s pressure by breakage of linkage connecting hydraulic plunger to retracting casting. Terrific air-pressure captured in wheel well and finally blowing out entire wheel well cell, coupled with drag of the wheel being extended at high speed tore off the wing. It is believed the flap was torn off as a result of the wing’s being torn off.

b. The second possibility is that, while travelling at comparatively high speed (not necessarily exceeding permissible diving speeds), and probably during a time when the aircraft was under the stress of positive “G’s”, the wheel fairing door extended itself sufficiently to allow air pressure into the wheel well cell. This could have happened either because of the fairing door not being positively locked, or due to warpage.

The door being allowed to partially extend was immediately ripped from the aircraft, and terrific air pressure was built up inside the wheel well cell, over-stressing the wing and causing the entire wing to flex sufficiently for the locking pin on the wheel to slip out of the up-lock, allowing the wheel, aided by air pressure and possible “G’s” to extend itself, over-coming the hydraulic system by breakage of the mechanical linkage connecting the hydraulic plunger to the landing gear retracting casting. A combination of the resistance caused by the landing gear extending at high speed, and the air pressure in the wheel well, over-stressed the wing, probably threw the plane into a violent skid or yaw, thus increasing abnormal pressure on the wing, causing it to shear completely off. The immensity of the air pressure built up in the wheel well is evidenced by the facts stated in para 3, e, above; i.e., that the portion of the wing housing and covering the wheel well cell was blown up and out, from the inboard gun, back to the main spur, and thence inboard along the main spar to the inboard end of wing.

5. Opinion It is the opinion of the board that whether material failure at #75 station started the train of events that led to the final shearing off of the wing, or air pressure getting into the wheel well cell, either due to warpage or of fairing door, or malfunction of fairing door locking devices, that the extending of the wheel and air pressure built up inside of wheel well cell over-stressed the wing and caused it to shear off.

Immediate Cause: Loss of control due to structural failure of left wing and loss of left wing.

Underlying Cause: It is this board’s tendency to lean towards the theory as outlined in para. 4, b, above, and that the wing was sheared off as a result of air pressure getting into wheel well cell, either due to fairing doors not being locked or due to warpage of fairing door, creating greatly abnormal stress on wing, causing it to flex sufficiently to allow wheel up-locking pin to escape, allowing wheel to extend, with the subsequent train of events as outlined in para. 4,b.

Responsibility: Inasmuch as there is no concrete evidence that the pilot was exceeding maximum permissible speeds, or “G’s” loads, and considering his past record in that he was considered to be a good and moderately conservative pilot (former bomber pilot), and that he had flown the aircraft sufficiently to be reasonably aware of its capabilities, it is the board’s opinion that the responsibility should be adjudged 100% Material and Structural Failure.

Recommendation: It is recommended that:

a. Consideration be given to lengthening the locking pin on the wheel that fits into the landing gear up-lock device, allowing the wing to flex with a lesser possibility of this pin to escape from the lock.

STATEMENT OF WITNESS

I was working indoors when I heard what I thought was an odd noise for an aircraft. I thought at first it may have been a new kind of jet plane. I went out to see what it was and I saw a Mustang minus one wing falling in a spin. It was fairly low when I first saw it, below the clouds, but at the time that the main plane left the aircraft, it must have been very high, because I saw bits and pieces falling for a long time afterwards. I did not see the pilot leave the aircraft.

/s G. E. Graddon

931793, L.A.C., GRADDON

R.A.F. Station Bentwaters, Suffolk

June 30th, 1945

P.51 Crash

I was duty Control Officer in the Watch Office at Bentwaters on the morning of June 30th. At approximately 10.36 hrs I heard the roar of an uncontrolled engine overhead and went on to the balcony. For almost a minute nothing was visible until a P.51 came through the clouds, then at 3,000 ft, with the starboard wing missing. Pieces of debris and what appeared to be a hood were following it down. The aircraft hit the ground on the far side of the aerodrome but did not burn. The pilot was not in the aircraft so I informed Sector and Group to institute A.S.R. as I imagined the pilot had baled out high up and with the prevailing wind would be blown out to sea. The Pilot, I was later informed, was dead having been found near the aircraft.

/s I. Hilcher F/Lt.

Control Officer

——————————————————————————

Click for the Engineering Officer’s AAF Form 54

Diagram and image links in this section courtesy:

1Lt Clifford W. Bransdor

RB-36H 51-13721, Newfoundland, Canada, March 18, 1953

On March 18, 1953, RB-36H-25, 51-13721, got off course in bad weather and crashed near Burgoyne’s Cove, Newfoundland, Canada. Brigadier General Richard Ellsworth was among the twenty-three airmen killed in the crash. A Boeing SB-29 Superfortress search and rescue plane failed to return from the search for the RB-36H crash site. None of the ten airmen aboard was ever found.

Synopsis of Air Force Aircraft Accident Report (added July 7, 2003):

Capt. Jacob Pruett Jr., Capt Orion Clark, Brigadier General Richard Ellsworth, Major Frank Wright and a crew of nineteen took off in RB-36H, 51-13721 of the 28th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing (Heavy) from Lajes Airdrome in the Azores at 0000 Zulu (11:00 PM Azores time) on March 18, 1953. Their destination was their home base of Rapid City Air Force Base, South Dakota. Their flight path took them across the Atlantic Ocean and over Newfoundland. The flight was expected to take 25 hours.

The pre-flight weather briefing indicated that their flight path would take them to the south of a low pressure zone. The counter-clockwise rotation of the low would produce headwinds that were forecast to average 17 knots from 300 degrees.

General Ellsworth and Major Wright were not current in take-offs and landings, so Capt. Jacob Pruett Jr. and Capt Orion Clark were probably at the controls during the take-off. Major Wright then moved into the pilot’s seat on the left and General Ellsworth got into the co-pilot’s seat on the right.

Major Wright and General Ellsworth flew the over water portion of the flight about 1,000 feet off the water for best range performance. They monitored their altitude above the water with the radar altimeter as they flew through the darkness.

The navigator intended to turn on the mapping radar an hour before the time that he expected the RB-36H to reach land. The pilots planned to climb to an altitude that would carry the RB-36H safely over the mountains of Newfoundland while they were still 20 miles from land.

Most of the flight was flown in overcast conditions that prevented the navigator from using the sextant for a celestial observation to determine the true position of the airplane.

The low pressure zone moved south of its predicted position before the RB-36H reached its vicinity. The airplane passed to the north of the low. Instead of the anticipated headwinds, the airplane encountered tailwinds that averaged 12 knots from 197 degrees.

Ocean station delta received a position update from the RB-36H at 0645Z. The navigator reported that the ground speed of the airplane was 130 knots. The position was in error by 138 nautical miles, and the true ground speed was closer to 185 knots.

The RB-36H reached Newfoundland about 1-1/2 hours earlier than expected. The crew made no attempt to contact air defense when they were fifty miles off shore. The navigator did not turn on the radar. The pilots continued to fly at low altitude. In the last twenty minutes of the flight, the ground speed averaged 202 knots. The visibility was less than 1/8-mile as the airplane flew straight and level through sleet, freezing drizzle, and fog.

At 0740Z (4:10 AM Newfoundland time), thirty miles after crossing the coastline the RB-36H struck an 896- foot tall ridge at an elevation of 800 feet. The six whirling propellers chopped the tops off numerous pine trees before the left wing struck the ground. The left wing ripped off of the airplane, and spilled fuel ignited a huge fireball. The fuselage and right wing impacted 1,000 feet beyond the left wing. The entire crew was killed on impact. Wreckage was strewn for 3/4-mile across the hillside.

U.S. Air Force 1st Lt Dick Richardson heard the RB-36H approaching his cabin at Nut Cove. The sound of the engines stopped suddenly, to be replaced by a loud explosion. Richardson reported that, “Everything lit up real bright”. He could see a fire burning on the hillside above. He woke up the other men on the hill. They boiled up the kettle and sent a search party up to the crash site through deep snow. They found no survivors.

Another RB-36H on a similar mission narrowly escaped a similar fate that night. Although still an hour from the estimated time of landfall, the pilot spotted land below the airplane through breaks in the clouds. He immediately initiated a climb to a safe altitude. It was determined that the airplane was 90 miles north of its intended flight path. Although the radar was operating, it was not properly tuned, so it failed to indicate the imminent landfall.

Also killed in the crash were: Capt Stuart Fauhl, Capt Harold Smith, Capt William Maher, 1Lt Edwin Meader, 1Lt James Pace, Major John Murray, 1Lt James Powell Jr., A/2C Robert Nall, 1Lt Clifford Bransdor, M/Sgt Jack Winegardner, A/2C Morris Rogers, T/Sgt Walter Plonski, A/1C Burse Vaughn, S/Sgt Ira Beard, S/Sgt Robert Ullom, A/2C Phillip Mancos Jr., A/2C Keith Hoppons, A/1C Theodore Kuzik, T/Sgt Jack Maltsberger.

The accident investigation board recommended that a forward looking radar should be developed to provide warning of high terrain ahead of an airplane. Navigators were instructed to scan for land with the radar every six minutes and pilots were instructed to climb to a safe altitude whenever the estimated position of the airplane was within 200 miles of land.

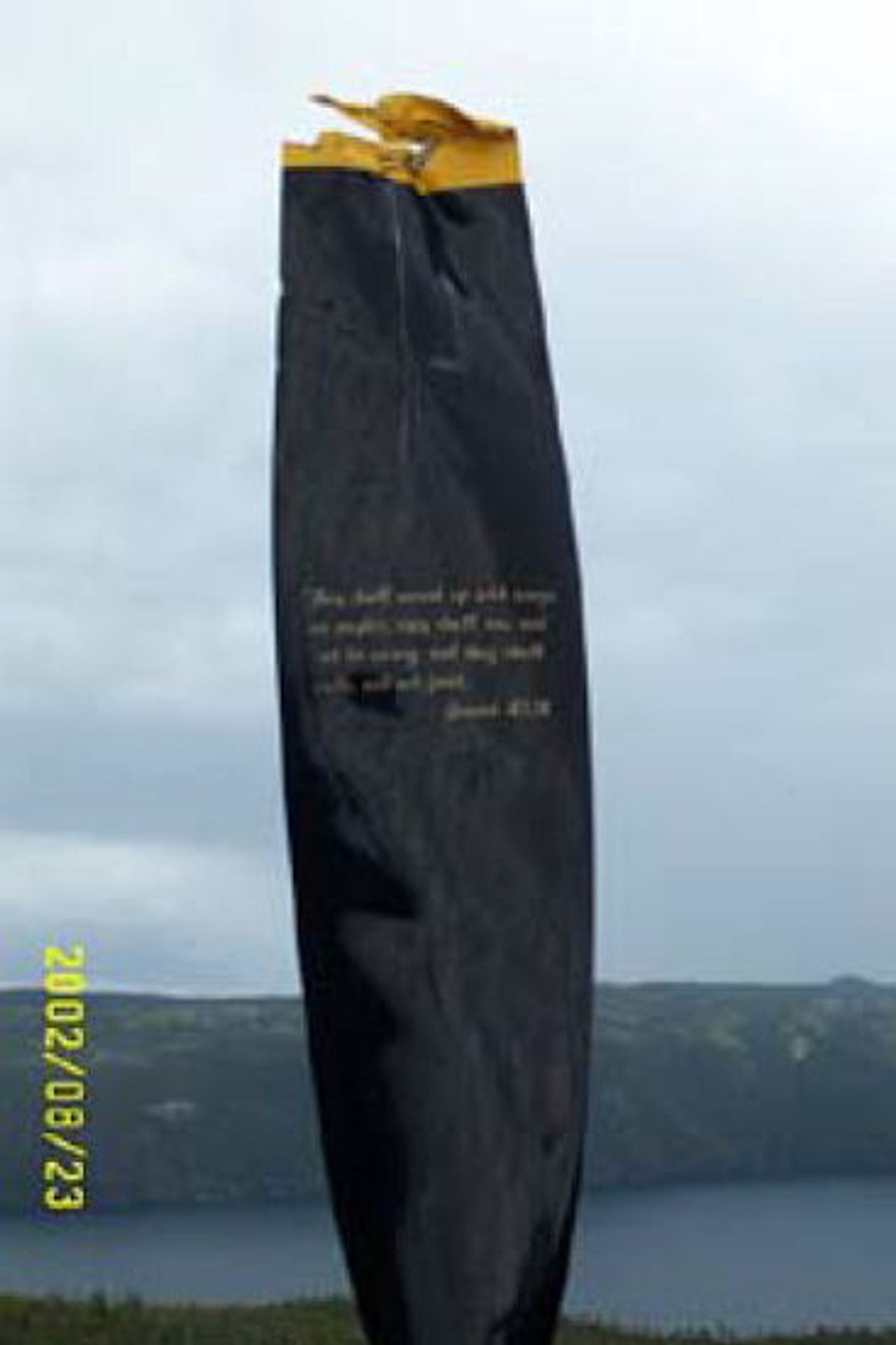

Crash Site Photos August 23, 2002

John Howley, a Resource Planner from the Lands Branch, Land Management Division, Dept. of Gov’t. Services and Lands, Gov’t. of Newfoundland and Labrador visited the crash site and took these photographs.

Propeller blade monument

(Photos: John Howley)

Crash Site Survey, August 2002

Neville Webb sent an update on the condition of the RB-36H crash site as of August 2002:

This particular aircraft wreck site is unique because of the size of the aircraft and the fact that most parts of the aircraft’s major structure are still in place. The wreck may be reached by driving east from Clarenville to Burgoyne’s Cove. A gravel road from Burgoyne’s Cove to a slate quarry further along the shore of Smith Sound, allows access to the trail to the site at Nut Cove. Until recently the only access to the site was by “walk-in” from Burgoyne’s Cove.

A new sign has been placed by the 515 Air Cadet Squadron, Atlantic Region, at the beginning of the trail. The trail climbs steeply through spruce woods and benches have been placed at intervals. The climb takes about half-an-hour and emerges onto the rock shoulder below the top of the ridge. A framed plaque has been placed at

the front bulkhead of the tail structure. This plaque shows a profile of the B-36H and gives reasons for the cause of the crash. Also a memorial consisting of a propeller blade from the aircraft and a stone memorial and bronze plaque are placed at the highest point of the ridge.

In general, the explanation states that two B-36H aircraft were on a secret mission. The mission was to fly from the Azores across the Atlantic at 500 feet altitude until reaching the Maine coast, then to climb to 44,000 feet and begin the actual mission. Navigation was hindered by fog and no fixes were made enroute. A low pressure area that was expected to move north in the Atlantic, and give winds to carry the aircraft south, did not move as predicted. Additionally, the aircraft steered a few degrees north to counter the expected southward trend. In fact, the winds around the low carried the both aircraft some 400 miles to the north, the second aircraft having a lucky escape from a similar fate.

The aircraft structure and engines are spread across the site on both sides of 650 to 700 foot ridge running approximately SW-NE. The site of the wreck is 481120N-533943W. The ridge at the wreck site is crossed by a steep side narrow valley which contains wreckage.

One purpose of this visit was to identify aircraft parts and provide a name for each area of the site where parts were found.

1. EAST AREA — where the trail emerges on to the shoulder, east and below the top of the ridge.

2. CENTRE AREA – the area beside a small pond.

3. VALLEY EAST – the beginning of the step sided valley that cuts through the ridge.

4. VALLEY WEST – where the valley opens to the lower ridges on the west of the ridge.

5. LOWER WEST RIDGES – ridges below the west side of the ridge line.

THE FOLLOWING IS A LISTING OF SOME OF THE PARTS FOUND IN EACH AREA

EAST AREA (to the left of where trail exits woods): This area consists of rocky gullies that run parallel to the main ridge and is about 80 foot below the ridge line. 1) Propeller spinner. 2) Engine cowling. 3) Jet engine pylon cowling. 4) Aircraft structure. 5) Fractured Compressor disc – probably from one of the port-paired jet engines. 6) Fractured wheel rim. 7) Wing structure. 8) Partial flap structure.

EAST AREA UP TO RIDGE: 1) Outer Wing structure: large section of wing structure. with some possible evidence of tree impact at leading edge. 2) Jet engine. 3) Piston Engine: embedded cylinders forward. 4) Piston Engine.

CENTRE AREA: 1) Assorted aircraft debris. 2) Nose wheel strut c/w steering gear. 3) fracture wheel rim (one). 4) Engine gear case. 5) Carburetor mounting and intake. 6) Engine supercharger impeller. 7) Propeller blade (tip damage). 8) Propeller blade (near small pond – severe blade bending rotation axis).

VALLEY EAST: (East to West) This is where the largest piece of the aircraft structure is found, namely the rear stabilizer, rear fuselage including gun turret and rudder. 1) Rear fuselage, fin, rudder (top of fin and rudder have broken off and lie beside structure. 2) Main Wing structure. 3) Propeller hub.

4) Propeller blade (drawing no. 1 129-17C6-24, serial no. 426128). 5) Gun turret structure. 6) Aircraft debris.

VALLEY WEST: This is where the where the forward fuselage structure is found including fire damage. 1) Fuselage structure including circular opening.(two fuselage rectangular box section beam at each side). 2) Cockpit framing. 3) Gun turret. 4) Twin main wheel and bogie. 5) Twin main wheel. 6) Crew seat. 7) Front fuselage skin with “– US AIR FO —” 8) Front fuselage skin with ” — 72 —” 9) Fuselage skin with circular access panel and panel. 10) Aircraft debris, wiring, small components. 11) Piston engine and associated local structure, cylinders facing forward (top left side of valley).

LOWER WEST RIDGES: This is area is to the west of and 100 feet below the ridge top. 1) Fuselage structure including circular opening.(one fuselage rectangular box section beam at top). 2) Wing section (peeled back and open) 3) Piston engine: impact evidence shows complete and some shearing of lower two pistons in cylinder each bank. 4) Engine cowling. 5) Wing section: top of section (actually the underside, shows USAF Star).

HYPOTHESIS OF ACCIDENT EVENTS: The terrain on both sides of Smith Sound (including Random Island) rises in places steeply from sea level. Terrain heights in this area range from 250 ft, 350 ft and up to 700 ft. Any aircraft flying at 500 ft in bad weather and approaching the coast at this part of Newfoundland would be fortunate to avoid flying into high ground.

1. The wreckage pattern suggests the B-36H first struck a sloping rocky edge to the east and about 70 ft below the SW-NE ridge. Finding a pylon structure at the EAST AREA, together with a jet engine and a single fractured compressor disc, together with a propeller spinner and cowling and a wing structure suggest an impact line at the level underside of the main wing surface.

2. The nose wheel strut and a fractured wheel rim in the debris at the CENTRE AREA suggests this unit free to move and fall just further on from the initial impact point.

3. The separation and direction of the tail unit suggests aircraft break-up, as the long fuselage, traveled up and along the rising ground toward the valley and ridge top. The tail section may have separated at the first impact with outer rocky edge and flipped.

4. The position of two piston engines on the east side of the ridge (at the left of the valley) show complete separation from the engine mount structure and tumbling slightly upwards and forward. These may have been the two outer piston engines of the port wing.

5. A third piston engine, on the top left side small valley, still has its local structure attached and rests with the pistons facing forward.

6. The question raised is whether the crew saw rising ground in the last few seconds before impact and attempted to climb through a small break or valley in the ridge line. In this respect, the front fuselage section went through the valley and most of the wing sections lie at the east end of the valley at the east side of the ridge.

7. Separation of the inner wing structure allowed two main wheel struts to follow the fuselage section through the small valley; these lie closely with the front crew area. One main wheel strut may have impacted through the crew canopy.

8. A partial fuselage section, an opened wing structure, a piston engine and outer wing section lie below the west side of the ridge suggest aircraft break up at or on the EAST AREA and the VALLEY EAST areas. The speed and momentum of the aircraft at impact may have allowed the wing section to lift and “fly” over the ridge.

SUMMARY

While the cause of the crash of B-36H 51-13721 was flying into high ground, the question remains whether the flight crew had any last second chance to climb and avoid the ridge. Clearly any warning to avoid impact came too late. However, there is a very slight suggestion from the layout of the wreckage and the fact that the tail section separated (fracturing upwards) and tumbled that the aircraft might have been in a climbing attitude before striking a rocky edge at the east side of the ridge. Fifty years have passed since this crash and only structure remains. Any evidence on-site as to power settings and controls is long gone or only to be found in crash reports. A visit to the wreck site is an interesting experience and worth the effort to climb the ridge and also see the memorial atop the ridge.

Crash Site Survey, August 2001

Neville Webb of Newfoundland previously visited the RB-36H crash site on August 18, 2001 and provided a description and photos of the wreckage:

A propeller at the top of the ridge forms the memorial with crew names. Photo courtesy: Neville Webb There is a steep climb 40 minute to the top of the ridge via a trail, accessed from the gravel road to the Slate Quarry at Nut Cove. The main wreck lies at the lower west end of a small steep sided valley that cuts across the top of ridge. The front fuselage section is burned out, with the ground covered in aluminum ash and related debris. This area has what is left of front cockpit window frames, pilot seat, turret, nose wheels and (RH) main bogy.

The tail section lies at the top of the small valley: of interest is the dead tree stump that has pieced the RH stabilizer. Of further interest is the fact that the tail section has turned 180 degrees to the line of the fuselage debris. Other wreckage may have gone over the ridge. Saw six engines and one jet engine. (Photos courtesy: Neville Webb)

Crash Site Survey Summer 2000

Sean O’ Brien visited the site in the summer of 2000 and reported:

It isn’t quite as remote as it may have been back in the fifties. In fact, after one parks one’s car, it is only about a kilometre hike on a well-groomed trail – with several rest areas along the way!

The plane had very nearly cleared the top of the six-hundred foot hill overlooking Smith Sound. The view from the hill is so beautiful, in contrast with the wreckage. The tail section is intact and perfectly upright. I counted seven engines in the area. There are large sections of wing scattered everywhere. Oddly, there is remarkably little fuselage evident. But maybe some of that was salvaged by local people. Certainly, most of the armament was. I saw an electrically-operated cannon mounted on the workshop wall of a local youth, who had only dragged the gun home from the scene some five years ago. And locals tell me that there are truckloads of bits and pieces of her sitting in cellars in all the nearby towns.

There are currently plans to improve and promote the trail leading to the wreckage as a tourist attraction.

Rapid City Air Force Base, South Dakota was renamed Ellsworth Air Force Base in honor of General Ellsworth.

A B-29 Superfortress and a B-36 Peacemaker at Carswell AFB in 1948

Synopsis of Air Force accident report for the loss of SB-29 Search Plane

Captain Francis Quinn and 1st Lt Robert Errico and a crew of eight took off in SB-29-70BW, 44-69982 from Ernest Harmon Air Force Base, Newfoundland at 12:10 on the morning of March 18, 1953 to search for Convair RB-36H-25, 51-13721. 44-69982 was assigned to the 52nd Air Rescue Squadron of the 6th Air Rescue Group.

The SB-29 was modified for the search and rescue role. It carried a 40 ft.aluminum boat under the bomb bay. The boat could be dropped by parachute. It had a 4-cylinder engine and rations for a number of days. It had an inflatable shelter at each end, and a tarpaulin could be zipped into place between the shelters to completely cover any occupants. A search radar was installed in place of the lower forward gun turret.

The SB-29 scouted the location of the RB-36H crash and determined that there were no survivors. It returned to Harmon AFB at 7:45 P.M. There were broken clouds at 2,700 feet and and a solid overcast at 5,000 feet.

Harmon tower advised Captain Quinn to turn to a heading of 180 degrees and handed him over to GCA. T Sgt. Robert Burgoon was the GCA operator on duty that evening. Captain Quinn reported that he was reading the GCA radio “five-by-five”. T Sgt. Burgoon instructed him to descend from 4,000 feet to 3,000 feet and maintain a heading of 180 degrees.

T Sgt. Burgoon read off the emergency procedure and current weather to Captain Quinn. Quinn acknowledged those transmissions, but when Burgoon read off the standard rate of turn, a different SB-29 crew member responded over the radio.

When the SB-29 appeared on the GCA radar scope about seven miles from Harmon AFB, it was flying on a heading of 220 degrees. T Sgt. Burgoon instructed Captain Quinn to turn right to a heading of 30 degrees to avoid losing the Superfortress’ radar return in the ground clutter during a left-hand turn. Quinn read back the heading as 300 degrees. Burgoon repeated that the proper heading was 30 degrees. Quinn read back something that Burgoon was not able to understand, so he reiterated his command to turn right to a heading of 30 degrees yet again. Quinn stated that he was initiating a left turn to 30 degrees, and Burgoon repeated that the turn was to be made to the right. Captain Quinn started his right turn and the SB-29 disappeared into the blind spot of the GCA radar.

When the Superfortress appeared on radar again about 11 miles from the base, it was inbound on the proper heading of 30 degrees. T Sgt. Burgoon read off the runway condition, landing runway, and braking action to Captain Quinn, but received no reply. He requested acknowledgement of his transmission twice with no response from Quinn. Burgoon commanded Quinn to turn to a heading of 300 degrees to determine whether he was still receiving the GCA transmissions. Burgoon repeated the command twice but received no response from the Superfortress, and it continued on a heading of 30 degrees.

The SB-29 was over St. George’s Bay about ten miles from the base on a bearing of 240 degrees when it disappeared from the radar scope at 7:51 P.M. It did not get lost in ground clutter. It just disappeared from a location where it should have continued to be visible. On one pass the blip was there, on the next pass it was gone.

T Sgt. Burgoon made several calls to the SB-29 in the blind, but no further transmissions were received from it. Pilot Captain Francis Quinn, Co-pilot 1st Lt Robert Errico, Navigator Captain William Roy, Navigator 1st Lt Rodger Null, A/3c James Coggins, A/3c Sammy Jones, A/2c Michael Kerr, S/Sgt David Kimbrough, A/1c David Rash, A/1c Robert Montgomery were lost in the crash.

At 8:15, an Air Force rescue vessel was dispatched to the area where the radar return had disappeared. DeHavilland of Canada L-20 Beaver, 51-16490 took off at 8:44 to search for any signs of survivors at the crash site. Sikorsky H-5G Dragonfly helicopter, 48-553 took off to conduct a search at 8:46. It was going on midnight when three more vessels joined the search.

An oxygen tank from the SB-29 was spotted floating in St. George’s Bay at 5:09 the next morning. Search teams found fuel cells, the radio operator’s table, air scoop dust covers, hydraulic fluid, an oxygen tank, the navigator’s brief case, a partially inflated six-man life raft, and other small debris from the SB-29. The few pieces of structure that were recovered showed evidence that the SB-29 had suffered major damage when it impacted the water. A total of fifty-three pieces of debris were recovered during the first day of searching. A buoy was placed at the oil slick where the debris was found.

Two L-20 Beavers searched the bay all day on March 19th.

The local countryside was scoured for witnesses. The H-5 Dragonfly was used to visit residences along the shoreline of the bay that were otherwise inaccessible. Civilian John Walters of Kings Head reported that he heard a loud explosion and saw a bright flash, “kinda like a red flame” about two to three miles offshore about 7:45 that evening. His was considered to be the most reliable eyewitness account.

The Dragonfly was flown to the location where the SB-29 had disappeared from radar. It made a series of descents and ascents. It was noted that it disappeared from the radar as it descended through about 800 feet.

Dragging and diving operations began on March 20. Forty square miles of ocean floor were dragged. Divers made sixty-one dives with negative results. The divers and dragging gear were unable to search below a depth of 200 feet.

The U.S.S. Salvager was dispatched from Norfolk, Virginia to search the bay with SONAR equipment. It arrived at the station on March 27, but it did not have suitable gear for locating the wreckage. UOL equipment and personnel arrived on April 5 and started searching for the SB-29 wreck on April 6. The UOL equipment was disabled by contact with rocks on the bottom of the bay on April 9.

The main wreckage of SB-29, 44-69982 and the bodies of her crew were never found.

Source Air & Space.com: RB-36H 51-13721, Newfoundland, Canada, March 18, 1953

Edward V. Day A2 Flight Jacket