Armour Crew – Assigned 754th Squadron – May 1944

Shot down June 29, 1944 – MACR 7092

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Crew Position | Date | Status | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2Lt | Charles B Armour | 0691465 | Pilot | 29-Jun-44 | EVD | E&E Report 2024 | |

| 2Lt | Donald E Blodgett | 0701868 | Co-pilot | 29-Jun-44 | EVD | E&E Report 2025 | |

| 2Lt | John O Fullerton | 0712547 | Navigator | 29-Jun-44 | EVD | E&E Report 2679 | |

| 1Lt | John M Beddow | 0701234 | Bombardier | Feb-45 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross | |

| S/Sgt | Jerome Brill | 33601860 | Radio Operator | 29-Jun-44 | POW | Stalag Luft 4 | |

| S/Sgt | Carry G Rawls | 34506572 | Top Turret Gunner | 29-Jun-44 | POW | Stalag Luft 4 | |

| Sgt | Frank Piechoto | 39411039 | Ball Turret Gunner | 29-Jun-44 | EVD | E&E Report 2680 | |

| Sgt | William F Owens, Jr | 35651617 | Waist Gunner | 29-Jun-44 | EVD/POW | Betrayed to Gestapo/Stalag Luft 4 | |

| Sgt | Billy J Davis | 38303263 | Waist Gunner | 29-Jun-44 | WIA/POW | Wounded/Stalag Luft 4 | |

| Sgt | Everett S Allen | 11105323 | Tail Turret Gunner | 29-Jun-44 | POW | Betrayed to Gestapo/Stalag Luft 4 |

2Lt Frederick H. Erdmann, bombardier on 1Lt Robert Davis’ Crew 49 (an original 754th crew) replaced Lt. John Beddow as bombardier on this mission. The crew was flying B-24 #42-51095, Shoo Shoo Baby over the target when the ailerons, and all four engines were damaged, presumably by flak. The ship “…lost 7,000 feet of altitude very fast”. Number 1 engine was feathered, and “…all engines were throwing gas”. Sgt. Billy Joe Davis was “…slightly wounded in the head by flak”. All crew members bailed out safely. Charles Armour, Donald Blodgett, John Fullerton, and Frank Peichoto evaded successfully through the Dutch Underground.

While Davis (head wound) and Rawls (broken ankle) were captured immediately by the Germans, William Owens, Everett Allen, and Frederick Erdmann evaded capture for a while as well, but were betrayed and turned over to the Gestapo in Belgium, and spent the rest of the war in a German Stalag [see William Owens narrative below]. Armour and Blodgett returned to England in rather short order, by September 12, 1944. Fullerton and Peichoto took a little longer arriving by November 21, 1944. Their abandoned aircraft crashed into a Dutch farm killing the farmer, his wife, and their 18-year old daughter.

Lt John Beddow completed his combat tour in February 1945.

————————-

MACR 7092

Interrogation of crews developed no information on ARMOUR. However, have received radio messages from A/C 095 stating that they were going to bail out east of ZUIDER ZEE and then that they had reached ROTTERDAM. Latest report was that NF/DF Sec E received message on Fix 5238-06000 that A/C was leaving coast at Rotterdam and following coast to Calais and cross there. This information was received by Flight Control, AAF123 [Horsham St. Faith], APO 558.

Missions

| DATE | TARGET | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 06-Jun-44 | VILLERS BOCAGE | 57 | 1 | 41-28733 | X | J4 | 30 | RHAPSODY IN JUNK | MSN #2 | |

| 07-Jun-44 | LISIEUX | 59 | 2 | 41-28682 | I | Z5 | 34 | UNKNOWN 003 | ||

| 08-Jun-44 | PONTAUBAULT | 60 | NTO | 41-28682 | I | Z5 | -- | UNKNOWN 003 | NO TAKE OFF - REASON UNK | |

| 10-Jun-44 | CHATEAUDUN | 61 | 3 | 41-29596 | R | Z5 | 18 | HELL'S ANGEL'S | ||

| 11-Jun-44 | BEAUVAIS | 63 | 4 | 41-29596 | R | Z5 | 19 | HELL'S ANGEL'S | ||

| 12-Jun-44 | EVREUX/FAUVILLE | 64 | 5 | 41-29596 | R | Z5 | 20 | HELL'S ANGEL'S | ||

| 14-Jun-44 | DOMLEGER | 65 | 6 | 41-29596 | R | Z5 | 21 | HELL'S ANGEL'S | ||

| 14-Jun-44 | DOMLEGER | 65 | ABT | 41-29596 | R | Z5 | -- | HELL'S ANGEL'S | ABORT - #3 ENG FUEL LEAK | |

| 15-Jun-44 | GUYANCOURT | 66 | 7 | 41-29596 | R | Z5 | 22 | HELL'S ANGEL'S | ||

| 19-Jun-44 | REGNAUVILLE | 71 | 8 | 42-52274 | H | J3 | 7 | UNKNOWN 029 | MSN #1 | |

| 20-Jun-44 | NOBALL FRANCE | REC | -- | 42-95018 | J | Z5 | -- | OLD DOC'S YACHT | MSN #3 RECALL | |

| 24-Jun-44 | CONCHES A/F | 77 | 9 | 42-51095 | Q | Z5 | 16 | SHOO SHOO BABY | MSN #1 | |

| 25-Jun-44 | ST. OMER | 80 | 10 | 41-29305 | N | Z5 | 23 | I'LL BE BACK/HYPOCHONDRIAC | ||

| 28-Jun-44 | SAARBRUCKEN | 81 | 11 | 41-29596 | R | Z5 | 27 | HELL'S ANGEL'S | ||

| 29-Jun-44 | ASCHERSLEBEN | 82 | FTR | 42-51095 | Q | Z5 | 19 | SHOO SHOO BABY | SHOT DOWN - FLAK |

June 1944 – Horsham St. Faith

Sgt William F. Owens’ – Evasion & Capture

While three of the crew were captured upon landing, and four eventually made their way back to freedom, three additional crew members evaded for a period, but were eventually betrayed to the Gestapo, as the underground line had been infiltrated. This is the account of Sgt William Owens, nose turret gunner. With him for much of the time was Lt Frederick Erdmann, Sgt Everett Allen, and Sgt Frank Peichoto. While he mentions Sgt Carry Rawls as evading, Mr. Rawls’ daughter stated that he broke his ankle upon landing and was in no condition to evade. He was picked up immediately by the Germans.

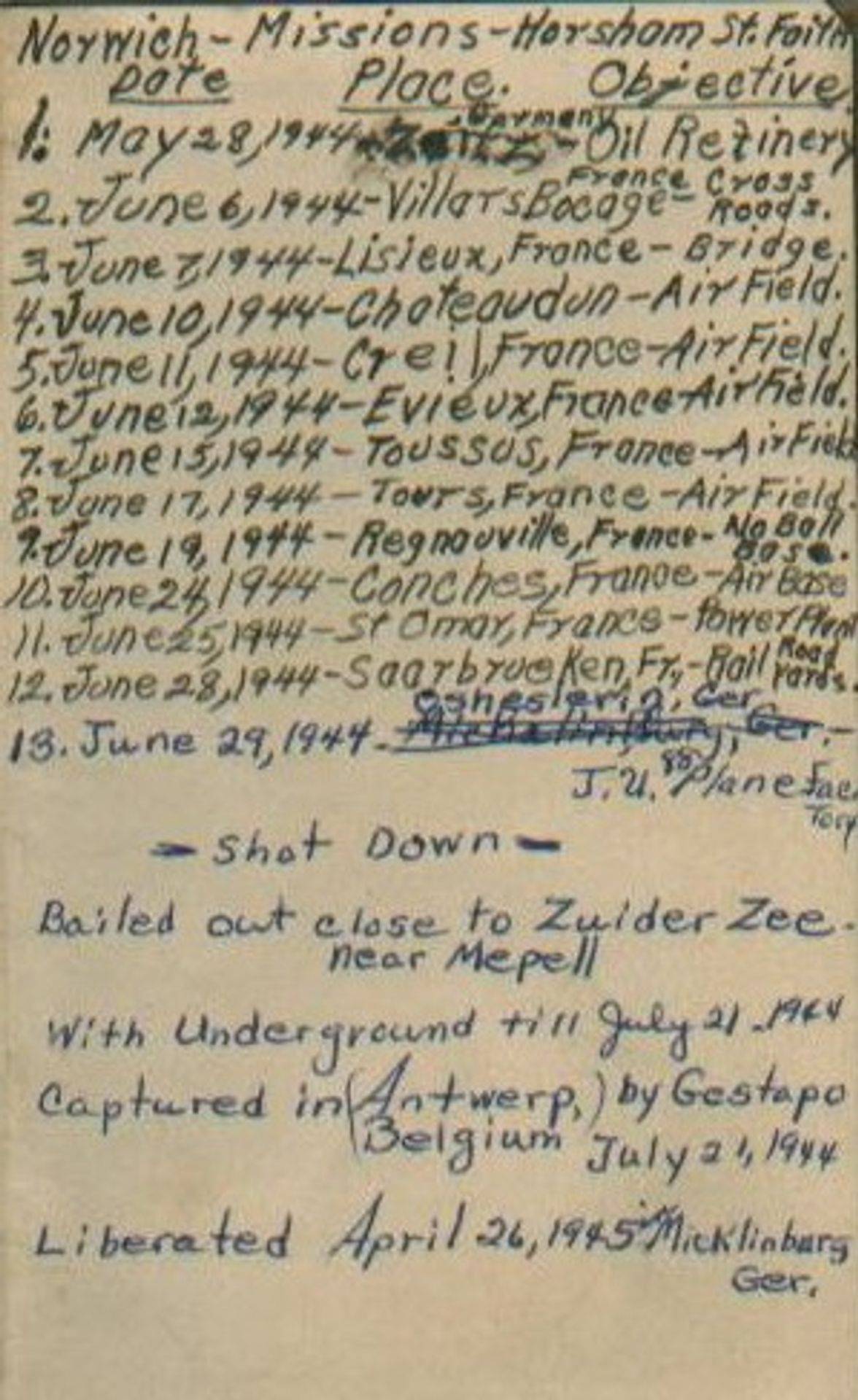

From May 28, 1944 through June 28, 1944 I was on twelve missions, with the flying time ranging from about four and half hours to eight hours per mission. The targets for part of these missions were in France supporting the invasion. I kept a record of each mission in the back of my New Testament, which the Air Force gave me on June 6, 1944 (invasion day). I still have this New Testament, which contains President Roosevelt’s signature.

Things hadn’t been too bad through these first twelve missions. Our plane was hit and damaged on some of the missions but none of the crew was injured. We were beginning to build hope that we might make it through the required twenty-five missions and be eligible to go home. All of this changed on my thirteenth mission. The early morning hours of June 29, 1944, had us preparing for another mission into the heart of Germany. This time our target was a JU-88 airplane factory. At the briefing we were told to expect heavy antiaircraft fire (flak) at and around the target. The large guns on the ground would fire at our planes, and the load was set to explode at a certain altitude. The explosion would create a large ball of black smoke and send out many pieces of sharp metal, which we would have to fly through. It could bring down a plane if it were a direct hit. We would usually fly at 20,000 feet or higher, but they could still reach us. We would have to climb to 20,000 feet over England before we crossed the English Channel and this would take several hours. This was in the days before jet planes. At this stage of the war the Germans were relying more on the antiaircraft guns than on their fighter planes. At times we would see their fighter planes but they would seldom attack us while our planes were flying in tight formation. They would wait for a plane that was damaged and couldn’t keep up with the formation. Their big guns were becoming more concentrated around the major targets. Flak was hitting more and more of our planes. The day before this mission, we made it back with a large hole in our wing. On the same mission our buddy crew was shot down. We went through Phase Training with this crew and became close friends. As their plane went down we could see some of them parachuting out of the plane.

I was flying in the nose turret on this mission (#13) on June 29,1944, and could see everything up ahead of us. As we approached our target the flak became heavier and the black puffs of smoke were everywhere. Our formation had to stay on a straight and level course so the bombardier in the lead plane could keep his bombsight on the target. We had to fly through the flak. The bombardier in the lead plane used his bombsight and the rest of the planes dropped their bombs when they saw his bombs drop. We had a switch in the nose turret that would drop our bombs when our bombardier wasn’t using our bombsight. I hit that switch and dropped our bombs as soon as I saw the bombs drop from our lead plane. Shortly after that we heard a loud explosion from anti-aircraft fire either in or just below our bomb bay section. Our plane immediately dropped about 5,000 feet and was damaged greatly. One of our four engines was knocked out, control cables damaged, oxygen system destroyed, and probably the worst of all, the fuel tanks in the wings were punctured and we were losing a large amount of fuel. Through all of this our Lord was still protecting us. Only one crew member was injured. Our waist gunner was hit in the head with a piece of sharp metal. His flak helmet saved his life. The metal cut through his helmet and into his head. He was knocked out for awhile but was later revived. After dropping out of formation, our pilot and co-pilot got our plane under control and we headed back toward England. We were able to maintain our altitude at 15,000 feet, but had a long way to go and we continued to lose fuel. Our own fighter planes would usually meet us at a certain point and protect the stragglers from the German fighters. We flew alone for awhile before we saw several fighter planes off in the distance. We first thought they were German planes coming to attack us, but as they came closer we recognized them as our own P-51 fighters. I thanked my Lord once again. It was a welcoming sight, and they stayed close by as we made our way back.

Our luck ran out as we flew over northern Holland. We ran out of fuel. If the fuel could have lasted a little longer we would have made it to the English Channel and ditched in the water. When one of our three remaining engines failed our pilot gave the order to bail out. It was only the navigator and myself in the nose of the plane and we had to exit through the nose wheel well. By the time I got out of the nose turret he had kicked the door open and jumped out. I started to slide out of the opening but my parachute harness caught on the door latch. The wind pushed my legs back against the fuselage under our plane. It was very difficult but I finally pulled myself back into the plane. This time I went out headfirst. We had been taught to wait until we got close to the ground before opening our parachute but I couldn’t wait. I pulled the ripcord shortly after leaving our plane. The chute opened and I gave thanks to my Lord once again. After I calmed down I looked at my watch and it was about 11:15 in the morning and it was very quiet. There was no sound at all until one of our P-51 fighter planes appeared and circled me several times. As I floated toward the ground my mind was filled with many thoughts. I was dropping into a strange country not knowing a word of their language. Things seemed bad but they could have been worse. I could have been seriously injured or even gone down with our plane. I thanked my Lord once again for protecting me and I regained some of His wonderful peace, which helped me to face what was yet to come.

It seemed like I was in the air a long time before getting close to the ground, but when I did it came up to meet me. I landed in a wheat field. It was a hard landing on my left side causing rather bad bruises on my left elbow and left knee. I later learned that the area in which I landed had been reclaimed from the sea and was below sea level. The wheat field had large drainage ditches, with smaller ditches draining into them. I disconnected my parachute and started down one of the large ditches, not knowing where I was going. Before long I heard voices and saw two men coming down the ditch carrying my parachute and life vest. One of them could speak English and he told me they were part of the Dutch Underground. We played hide and seek in the wheat field, keeping away from the Germans until we reached the place where he wanted me to hide in the wheat. He told me to stay there and they would come back later. I thanked my Lord once again for sending help. I waited a long time and no one showed up, but I didn’t know of anything better to do so I continued to wait. By this time I was getting rather hungry, thirsty and sleepy, so I went to sleep. I don’t know how long I slept, but it was dark when I felt someone shaking me. It was the two men. They brought me two meatballs and two bottles of green pop. After eating I followed them to the home of a policeman where I spent the night. The next morning they gave me civilian clothes (rubber boots, shirt and pants) and took me into Meppel to stay with another family and wait for my phony passport and working papers. My passport listed me as a dentist born on June 6, 1919, and my name was Hendrick Bloomhoff. After receiving my passport and working papers, I went with a guide to the train station to ride the train down to Amsterdam.

I was in for quite a surprise when I reached the station. I was walking around on the platform and noticed other young men walking around. They were all wearing civilian clothes and one of them looked familiar. On closer look I recognized him as Billy Joe Davis, the waist gunner on our plane. I started looking closer at the other men as I walked and noticed that Edward S. Allen, tail gunner; Frank Peichoto, ball gunner; and Carry Rawls, top turret gunner; were also there. [Davis and Rawls were actually captured upon landing.] All five of us had made it to the ground safely and were picked up by the underground. We couldn’t stop and greet each other but it was a wonderful feeling to be together again and we would smile as we walked past one another. I gave thanks to my Lord once again.

All five of us got on a first-class train along with three guides and headed for Amsterdam. The underground didn’t want more than two of us traveling together with a guide, so when we got to Amsterdam we were divided into pairs of two. My partner was Frank Peichoto. Frank and I went through gunnery school together and became close friends. Then we were fortunate enough to be placed on the same crew. Now we were together again in the Dutch underground. We traveled together for the rest of the time we were in Holland. The two of us, along with our guide, were standing in front of the train station in Amsterdam waiting for a streetcar. Frank was smoking a cigarette and we noticed a German sailor coming toward him. The sailor was holding an unlit cigarette between his fingers and was bringing it up to his mouth as he said something to Frank in German. Frank, not knowing what the sailor said but anticipating his need, reached out his cigarette without saying a word. The sailor lit his cigarette from Frank’s and said, “Danke schoen” (thank you) as he went on his way. This was the first close encounter with the Germans and there would be more.

We stayed in Amsterdam with a man named Davis and his family for several days. He had been the Chief of Police before the war, but now was the head of the underground in that area. People came to him for advice and brought parts of guns or anything that could be used by the underground. We traveled by train only one other time. On that trip, along with several others, quislings (Dutch police in sympathy with the Germans) checked our passports. Our guides did the talking and we always got through. Most of our travel from this point was by bicycle, motorcycle, automobile and walking. At one time I rode on a motorcycle with a Catholic priest. Another time I rode in a 1932 Chevy with a wood burner attached to the back of it to create the fuel to run the engine. The engine kept running as long as there was fire in the burner. I can’t explain the mechanics of this contraption but it was a fascinating means of transportation and was greatly needed since gasoline was so scarce. Bicycles were a great means of transportation in Holland then, as it is now. When we were using bicycles or walking, our guides would tell us to stay some distance behind them in case they were stopped. If they were caught helping us they would have been put to death. On one bicycle trip we were following our guide on a road that was on top of a dike next to a canal. The water in the canal was higher than the land on either side of it. We were several hundred yards behind our guide when two German soldiers stopped him. We couldn’t stop when we got to him because we would have given him away. We kept riding along slowly until we got out of their sight and decided we had better stop and wait. We went over in the woods at the base of the dike and waited several hours but our guide never came. Finally another man stopped close to us and motioned for us to follow him. We followed him back the same way we had come until we came to a side road crossing the canal. We followed him on that road for several miles and found our guide waiting for us. He explained that the German soldiers were suspicious and he couldn’t follow us since the road crossing the canal was our turning off place.

We traveled almost the full length of Holland in the twenty-one days we were there and stayed in seven or eight different homes. One of the homes was on a farm out in the country. The house and the barn were all one building. The house was on one end and the barn with the animals on the other, but they both were very clean. Their pigpen was as clean as their kitchen. The men still wore wooden shoes or rubber boots while working in the fields due to the damp soil. I remember helping the ladies shell green peas for several hours while I was at this home. We stayed in another home that was an apartment, and there were German soldiers housed in the adjoining apartment. The people we were staying with told us not to talk out loud that night in our bedroom because the soldiers would be able to hear us. Their bed was right beside ours. Only the wall separated the two beds. While staying at another home I wrote a letter to my parents explaining all that had happened. I told them I was not injured and was with the underground in Holland. It was a rather long letter in which I told them other things like how much I loved them; what wonderful parents they were; how anxious I was to see them again; etc. A young man at this home said he would keep the letter until after the war was over and mail it for me in case I didn’t make it back home. He did mail the letter and Mom and Dad received it before I got back to the States. By that time my parents knew I was O.K. They had received letters from me while I was a prisoner.

The last home we stayed in before crossing the border into Belgium was in the small town of Erp. Two schoolteachers and their brother lived there and this was the first home where we could spend some time outside of the house because it was a small town and a secluded back yard. It was one of the few places where I didn’t feel the stress of being hunted by the Germans. We stayed there about four days waiting to cross the border into Belgium. They made pictures, which they later sent me along with some souvenirs (small wooden shoes and a spoon made of Dutch coins). Copies of these pictures can be found in the back section of this notebook.

Sitting on bench: Frederick Erdmann, unknown helper, Frank Peichoto, William Owens

(Photo: Michael LeBlanc)

It was at this home that Frank Peichoto and I separated. Our bombardier (not regular but flying with us the day we were shot down) was already waiting at this home. They would send only two of us across the border, so Frank and I tossed a coin to see which of us would go with the bombardier. I won the toss to cross the border with the bombardier, but I think I might have lost in the long run. I found out later after I got back in the States that Frank took a different route across the border and made it through Belgium, France and across the rugged Pyrenees Mountains into Spain, which was a neutral country. He said it took him about six months. Through correspondence after the war the schoolteachers told me they were using three routes to cross the border and two of the three routes had been infiltrated by the Gestapo (German secret police) at the border. Frank took the route that wasn’t blocked and made it to Spain. They also said the Germans had captured their brother and was planning to kill him for working in the underground. He was saved by the fast- advancing American Army. After fifty-eight years I still have great admiration for those people I met in the Dutch underground. They did everything they could to help us. They were sincere, brave and courageous people who loved their country more than life. They would have been killed if they had been caught working in the underground. I was under great stress most of the time, feeling like someone was behind me ready to grab me. Yet, even under those conditions, I enjoyed meeting those wonderful people and traveling through that beautiful and fascinating country. I will always be thankful for all they did for me and I will never forget them. Thank you Lord for such great people and the privilege of knowing them.

The bombardier and I left Erp with our guide and crossed the border into Belgium. We stopped on the outskirts of another small town and our guide told us to stay in a wheat field and someone would come to guide us from there. Quite sometime later two young women came and said they would take us to Antwerp. From this point things seemed different. The women didn’t go ahead of us as our other guides had. They walked beside us and talked with us in English. After stopping at a sidewalk café and eating currants, they took us to a family in the suburbs of Antwerp. We stayed there for two days with a great family consisting of the father, mother, ten-year old son and eight-year old daughter. One of the young women that guided us into Antwerp came back and told us she would take us into the center part of Antwerp and we would ride an ambulance down to Brussels. We went in a building and she introduced us to two men who were to take us to Brussels. They took us to an office on the fifth floor of the building and told us to empty our pockets that we were in the hands of the German Gestapo. At first we thought they were kidding but it didn’t take long to see that it was for real. They said that since we were in civilian clothes and had phony passports and working papers we would be shot for being spies. We told them we had our dog tags to prove our identity and one of them said the tags meant nothing, as he pulled out a pair of American dog tags. They had us really stressed out this time, thinking there was a possibility of being shot.

From there they took us to an old civilian prison in Antwerp where we stayed for two weeks. The building must have been a hundred years old. The cell I was in with three other men was about ten feet by twelve feet, with one small window in the back. The bedding was burlap sacks stuffed with wood shavings and bedbugs. We would spread the sacks on the floor at night and the four sacks would take up all of the floor space. The bedbugs would feed on all of us, but it seemed the men sleeping on the two outside sacks were the main food. We wore all of our clothes, including our shoes, during the night. The bugs would feed mainly on the exposed skin, which included our face, head, hands and wrists. Allen (tail gunner on our crew) was also in this cell, and he chose to sleep on the outside sack before knowing about the bedbugs. Within a few days his face and hands were covered with red whelps. Each morning we would roll up the sacks and stack them in a corner. The prisoners that were there before us had played a game with the bedbugs. They drew a line about half way up the wall and would try to kill the bugs before they could cross the line as they crawled up the wall. The bottom half of the wall was polka-dotted with the residue of smashed bedbugs. The first day we were there the guards came by and pitched in four chunks of brown ersatz bread. We took a bite and the bread was so bitter we thought it was made of spoiled dough, and laid it aside. The next time they gave us bread it had the same taste, but we were getting hungry enough to eat it. I learned later that one of the ingredients in the German ersatz bread was wood pulp.

There was no running water in the cell, but they would give us water to drink once in a while. The only toilet facility was a two-gallon water bucket that looked like it hadn’t been cleaned for years. The coating on the inside of the bucket was at least an inch thick. It stayed in a corner close to the door with a screen in front of it and they would empty it once a day. We learned that there were other American airmen in the prison and discovered a way of communicating with them. We would place our metal drinking cup on a two-inch metal pipe that ran along the back wall of the cell and talk into it. The other prisoners could place their cups on the pipe with their ears in their cups and hear us. It was a great way to pass time.

After about two weeks they took us, along with about thirty-two other American airmen, to the back of the prison and lined us up against a tall brick wall. At that moment I thought about the man saying we would be shot for being spies. I was waiting for the Germans to appear with their rifles and start firing. Instead they opened large wooden gates some distance down the wall from us and backed in a big truck. This turned out to be the trip to Brussels that the woman had promised. They kept us in Brussels a day and a night for interrogation, which was very brief. All that we were required to tell them was our name, rank and serial number. They didn’t try very hard to get any more than that, since they seemed to have all the information they wanted to know. They did question the radio operators longer, trying to find out more about our radar. We were in solitary confinement all night and part of that day. They put us in small compartments (no windows) only large enough for a cot. A drop cord with one light bulb hung from the ceiling. They would turn the light off during the night. My compartment was next to the outside wall and I heard German solders singing. One of the songs was “Lili Marlene” and it was beautiful. I was in solitary confinement for only twelve or thirteen hours but that was long enough. They put us on a train in Brussels to take us to Germany. This trip from Brussels to Frankfurt, Germany, was the most pleasant part of my prison stay. Although the train was packed with prisoners and very crowded it was a wonderful sight-seeing tour. We went through the northern part of Luxembourg and traveled for some distance along the Rhine River. The winding river with ancient castles built on its banks was beautiful. The beauty of God’s creation was evident even under those circumstances.

We crossed the Rhine River very slowly on a temporary bridge at Cologne, Germany. This part of the city looked like one big pile of bricks and rubbish. I didn’t see a single building standing. It was shocking to be on the ground and see what our bombs had done. Seeing all of this destruction brought me face to face with reality. I knew that the many bombs we had dropped had created great loss to both property and people, but I had been able to block it out of my mind. After seeing this close up scene of Cologne I could no longer block it out. I had to deal with it. After giving it a lot of thought, I realized I shouldn’t lay a guilt trip on myself. We were dropping those bombs and fighting the war to blot out evil. By stopping Hitler and ending the war we probably saved more lives than we destroyed. There is no way of knowing how many lives we destroyed or how many we might have saved.

I can think of only one life that I actually had a hand in saving. There was nothing heroic about it. I just happened to be there when he needed help. It happened while we were testing new engines that had been installed on our plane. We were flying at high altitude and were using oxygen masks. Billy Joe Davis and I went along mostly for the ride, and we were in the waist looking out the side windows. He was on one side and I was on the other. We were counting the many air bases below and talking to each other over the intercom. There was a pause in our conversation for a brief time when I felt something hit my back. It was Billy Joe falling against me. I notice that his oxygen hose had pulled loose from his regulator and he was passing out due to the lack of oxygen. I plugged his oxygen hose back into his regulator and turned the oxygen supply up to high and in a few moments he was back to normal. We were the only two in the waist of our plane. He wouldn’t have made if he had been alone. Thank you Lord, for placing me there with Billy Joe. Billy Joe was the person that was injured when our plane was hit by flak.

We had more interrogation and solitary confinement at Frankfurt, which was very similar to what we had in Brussels. Frankfurt was another destroyed city. We went from Frankfurt to Wetzlar, Germany, where we stayed for several weeks. This was a very nice camp as far as prison camps go. The Germans allowed an American Colonel (also a prisoner) to have almost complete charge of the camp, and he had it well organized. It was at this camp we received Red Cross packets containing clothing, including a sweater, a toothbrush, etc. This was my first tooth brush except for a homemade brush given to me when I was in Erp, Holland, which I still have. These two brushes had to last me until I was liberated. I never had toothpaste. I still have that homemade brush. I was really glad to get the clothing. I was still wearing the civilian clothes that the underground gave me. While at Wetzlar, I remember seeing two Negro pilots who flew P-51 fighter planes out of Italy. They had to bail out of their planes while flying at top speed. The whites of their eyes had turned blood red due to the air hitting them with such force. It was a strange sight. They took us from Wetzlar to Stalag Luft #4, one of the main prison camps for Air Force non-commissioned officers. It was located near the Baltic Sea, about twenty kilometers southeast of Bergard in the Pomeranian section of Poland. The Germans had defeated Poland earlier in the war and had built several other Stalag Luft camps in Poland, along with several infamous concentration camps.

After being separated from the others in Erp, Frank Peichoto spent another several months evading, and eventually made it back to England in November 1944.

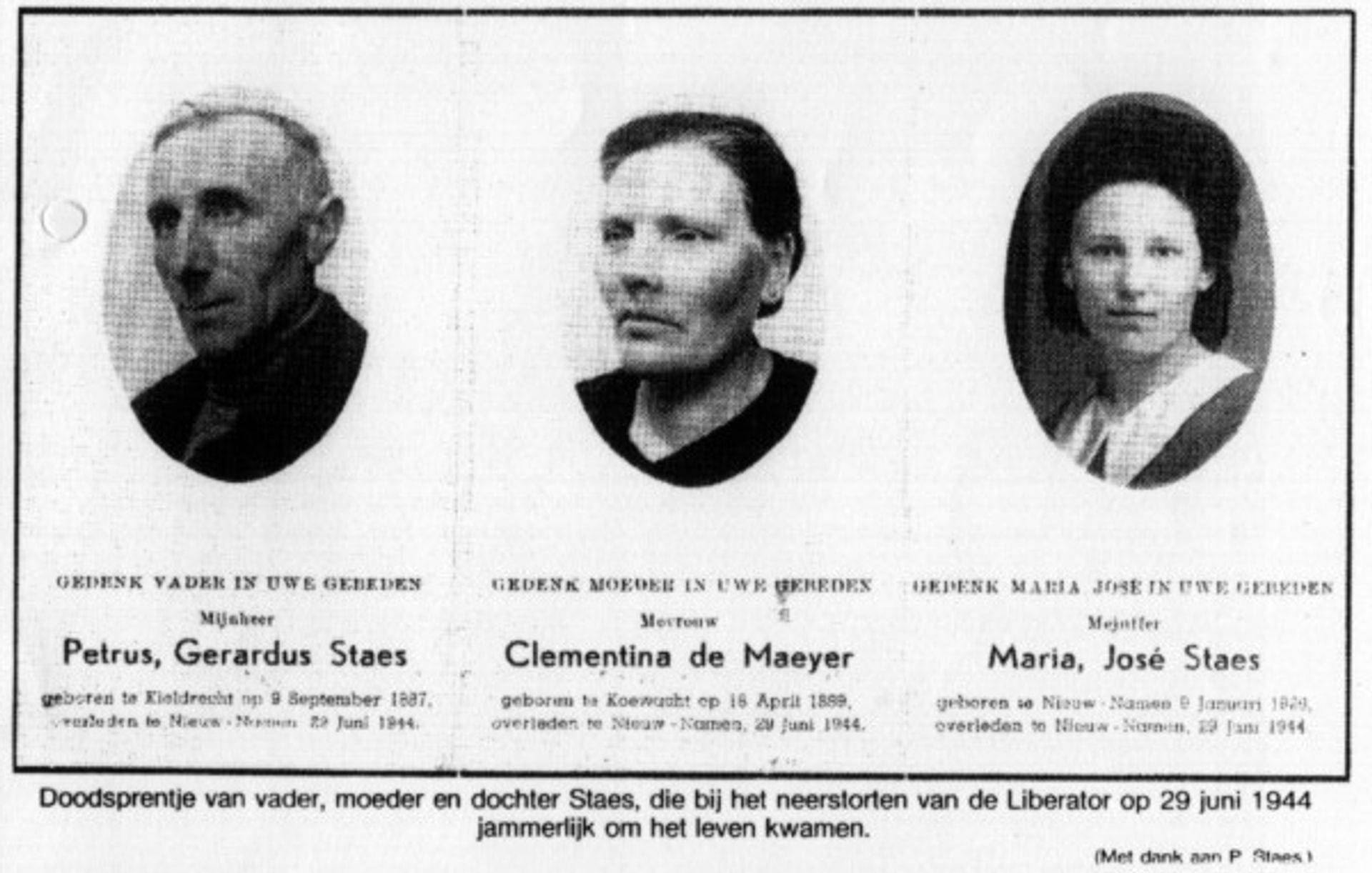

The Last Flight of the Shoo Shoo Baby – compiled by Jaap Geensen

Most of the time when a Liberator did not come home from a mission over Germany it meant that some of the crew and too often the whole crew did not return either. The crew of the Shoo Shoo Baby was lucky: eventually all ten of them returned home. One could say: a happy ending. However… what they did not know was that after they all had left the crippled ship it flew on, made 180 degree turn and crashed after losing more altitude into a farm, killing the farmer and his wife on impact and mortally wounding their 18 year old daughter. Thanks to the fact that the complete crew survived we were able to reconstruct the events around this tragic incident.

2Lt Charles B. Armour – Pilot

Over the new claimed land West of Vollenhove six of the crew bailed out. Engine # 1 was out, fuel system damaged, interphone, radio and oxygen system out. From Vollenhove he chose to fly south and see if they could make it to a base in liberated France. They made it past Rotterdam and flew parallel to the coastline [the first German Flak line which they preferred not to cross]. Four crew remained on board: Pilot and co-pilot, radio man and the Top Turret Gunner/Engineer. After the six jumped the a/c limped 250 Kilometers home till at a position West of Antwerp it became clear that they were not going to make it to a safe landing place. There the other four, Armour, Blodgett, Brill and Rawls also bailed out.

Brill and Rawls were immediately taken POW as they jumped more or less on top of the Germans, Armour and Blodgett left the plane a bit later and were “caught” by local Dutchmen and hidden on the Koningin Emma Boerderij (Farm) a couple of hundred meters away from where the plane crashed. His narrative: I hit the ground in the vicinity of Hulst, as did Lt. Blodgett. About 50 people were waiting for me in the field where I landed. I asked them to disperse and started to run. I ran along behind some houses taking cover behind a hedge. One man mentioned to me to hide in a wheat field near by and I took his advice. After hiding in the wheat for about an hour, I heard some one shouting “Hello”. I was afraid it might be a German trick and did not answer.

At about 19.00 hrs a man came to the exact spot where I was hiding and oriented me with a map he had with him. I asked him to get in touch with some one who spoke English. He indicated that I should remain in hiding. At about 23.30 hrs four policemen from Hulst came to get me and guided me to a farmhouse where the remainder of my journey was arranged. My story from this point on is almost identical with that of Lt. Blodget’s.

2Lt Donald E. Blodgett – Co-pilot

After he arrived back in England he reported the following on the situation when he bailed out: # 1 engine was out, we were out of gas, oxygen system was partly out, interphone and most of the radio was out. Waist gunner Davis was injured in the head by Flak. I bailed out at About 12:00 hrs and at 10.000 ft. The a/c crashed N.E. of Antwerp [in fact northwest of Antwerp] All parachutes to my knowledge opened.

In the narrative with the questionnaire he describes it as follows: “Our target was a JU-88 assembly plant at Eisleben Germany. Just about the time we let our bombs go, we were hit by flak and we had to drop out of formation. We headed for home , but when we were over the Zuider Zee [at that time it had been renamed: IJsselmeer], our engines quit. We decided to head back towards land, and the order was given to bail out when we were no longer over water. Lt Armour, the radio operator, the engineer and I bailed out near Hulst, Belgium [actually Holland] I landed in a meadow, picked up my chute and ran for some civilians standing in the field.

They took my chute, harness and Mae West but indicated that Germans were in the area. I began running across the fields for about a mile. When I came to a road, I hid in the field, until nightfall, not wishing to cross the highway in daylight. That night I started south and after walking about three miles, came to a flooded area and had to retrace my steps. I then met a man on a bicycle who appeared friendly. After I told him that I was American, he took me to a café in a small village, gave me civilian clothes and arranged to hide me in a house in the flooded area. I was taken to the house by rowboat and from that point on my journey was arranged.

From the farmhouse in the flooded area I was taken by two policemen to the home of Maria Wesemael on the Koning in Emmahoeve North of Hulst. I remained there until 9 July. From 9 to 12 July I stayed at the house of George Smet in Sint Niklaas, Belgium. A Mr.Richard Van Hoecke appeared to be the head of the organization in that district. I was later taken to the home of Octaaf de Boever, Langevelde 26 in Zele, Belgium where I stayed until that area was liberated.

2Lt John O. Fullerton – Navigator

In his debriefing on November 21st 1944 he states that he left the a/c near Vollenhove at 11.30 hrs. altitude was 12.000 ft. Ailerons shot up, engine # 1 feathered and other engines throwing gas. Waist gunner Davis hit by flak in the head. Six chutes opened. He is quite elaborate in his narrative which follows here: I landed in a level wheat field in the North East Polder, new reclaimed land from the Ysselmeer since 1942. There were some farmers working in the field. They rushed up to me and hid my chute and other equipment almost as soon as I landed. I could not see what had become of the others, so I hid there in the wheat until that night when two of the Dutchmen came and took me to the nearest village, VOLLENHOVE, in a car. They dressed me in civilian clothes over my uniform, and gave me some food. Later that night the bombardier came in. We stayed that night in house which was the organization headquarters. Next morning we went to MEPPEL by auto. We stayed there one night, and then went to Amsterdam, where I stayed in a house on the East outskirts of the city. Six of us were there altogether (myself, Peichoto, Erdmann, Davis, Owens and Allen).

We were taken to Amsterdam in pairs, with three guides, on the train.We stayed there at Zaandijk for 5 days. Food was very scarce and there were a lot of Germans around. On the 7th of July we were taken to VEGHEL, a small place near ‘s Hertogenbosch. We were told we would be sent to France from there. All except Peichoto and I left after one night for Belgium, and this was the last we saw of them. The bombardier was talking all the time and took too many chances, so I think they may have been caught. S/Sgt Peichoto and I went to ERP for a short time, then to BOXTEL by auto. We stayed there with a woman for three nights, then went on to a farm near DEURNE for two nights. The Germans were active in the neighborhood and the organization was afraid to let us stay in one place very long. They had heard that many airmen had been caught in Belgium lately and decided not to send us there for a while (see Owens’story), but to wait and see how the fighting in Normandy turned out. At another farm just after this we met Lt. Tracy and Sgt Garafalo [see E & E report Nos. 2678 and 2681] who were with us from now on. Two RAF sergeants C. Raymond Francis and Dennis Sharpe, were also there. (Both are now back safely). Later we all moved to still another farm near DEURNE.

On the 18th or 19th of July we took a train from VENRAY to HOENSBROEK in the province of Limburg. There we stayed at the home of a Dutch policeman for 10 days. The idea was to send us into Belgium through this route via Maastricht as it was safer, but after a while they sent us back to ROERMOND instead. We were taken to stay in a barn on a farm near HEYTHUISEN. Twenty-two evaders in all were being sheltered there. We stayed two weeks but moved on when things began to get hot. I heard that the place was raided by the Jerries later. The food was very poor. Sixteen of us were sent on to Belgium about the middle of August , but we stayed on, hiding in camouflaged shelters in the woods during the day., as there were so many Germans around. This was near ROGGEL. We spent another two weeks there, getting only a couple of sandwiches a day. “Twee vlees en een jam” We had stolen German blankets but no beds or heating. Next we went to KELPEN, again to stay “Bij de boer” (at the farmer’s) until the middle of September. On Sept 11th we went to LEVEROY in Limburg. This was a much better place and we stayed there, living in the barn until about October 30. The English had advanced and were right across the canal, less than ½ mile away. There were lots of Germans around and towards the end we went to live in a haystack, as they kept coming in the house for food. A German battery was set up less than 50 yards away. It became difficult to become food from the house, so at 04.00 hrs on Nov. 1st I left alone for KELPEN to try to get help. I stayed there until 15 November, when the British released me and also the others.

S/Sgt Jerome Brill – Radio Operator

Jerome Brill was the radio operator on that memorable day. He had flown 12 missions. On these earlier missions three of the crew’s Liberators were damaged in such a way that they were put in a different ship. On the 29th they boarded their number 4: Shoo Shoo Baby. Jerome: “I have no idea why this name was chosen. With all a/c we went to Oschersleben, southwest of Berlin to hit the aircraft industry there. During the bomb run we were hit by heavy flak. I was standing on my flak jacket looking through the open bomb bay doors to see if I could see our bombs explode on the target. We were blown out of the formation and were rapidly losing altitude. Both outside engines were damaged and had to be switched off. The main fuel tank over my head was punctured and we pumped out the fuel on the double in an effort to avoid the nearly always fatal fire. Also our landing gear had been damaged but we managed to get out of the dive and levelled the a/c flying on the two inside engines. I crawled through the bomb bay to the tail and saw that the left waist gunner Billy Joe Davis had been wounded on the head. I gave him first aid and returned to my position. In the meantime we were flying over the IJsselmeer.

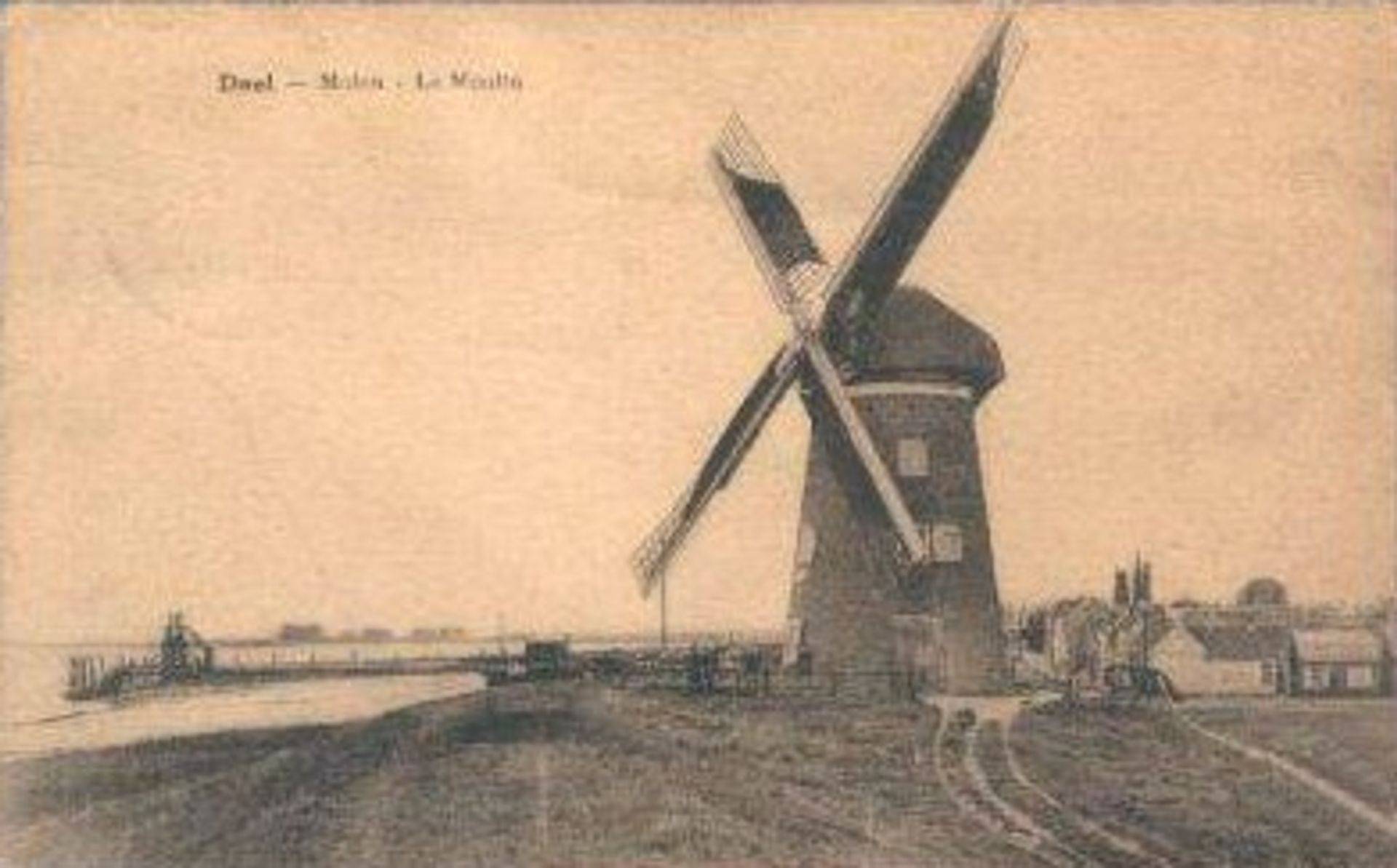

It was in that area when the first six left the a/c. They were: 2nd Lt John O Fullerton (Navigator), 1st Lt Fredrick H. Erdmann (bombardier), S/Sgt Frank Peichoto (Belly Turret Gunner), S/Sgt William E. Owens (Right Waist Gunner), S/Sgt Billy J. Davis (Left Waist Gunner) and S/Sgt Everett A. Allen. [They all landed in the Noord Oost Polder, new reclaimed land since 1942. They came down near Vollenhove, the closest village on the mainland.] As the chances to execute with success an emergency landing in the sea with such a damaged a/c were too small the pilot decided to fly South. When it became clear that we were not going to make it to near Normandy we also received orders to leave the ship. After we had destroyed some electronic equipment the Engineer S/Sgt Rawls and myself parachuted out. In a serene silence I floated several kilometers to eventually land into a canal [this was actually the river Scheldt near the village of Doel, Belgium] I managed to get clear from my parachute and saw German soldiers waiting on the shore. A small boat fished me out of the water and we got ashore in a small dock were I was taken prisoner [the two civilians who rescued him wanted also to rescue the parachute they were however disturbed by the Germans who were using the nearby windmill as an observation post].

Postcard of windmill where Brill was captured (Jaap Geensen)

There were some villagers around and because I was Jewish and had learned French at school I understood their signs of sympathy for me. We walked a short distance to a windmill where I took off my wet clothes and could warm up in the sun. After a while also Rawls was brought to the windmill. He was wounded on the leg while landing (he had a broken leg). We were transported on a truck to Antwerp. We passed the wreck of our a/c that had crashed onto a building…..” [The German truck must have made a detour of several kilometers, this was probably done deliberately.]

On the ground in Holland

A farmhand working on a farm in those days owned by Jacobus Verhagen, Hulsterweg in Terhole (3 Km North of Hulst) tells us: “We were weeding in the sugarbeets near Rust Wat (10 Km West of crash site) in the Dullaert Polder . From the direction of Nieuw Namen came an aircraft. It was flying very low, not higher that 50 meters (150 feet) and we could see that the cockpit was empty. Suddenly it turned 180 degrees and flew back into the direction from where it came. Moments later we saw smoke going up. We thought it had fallen near Schuddebeurs but when we took our bicycles it appeared to be further away than we thought.

On the land of farmer Staes

Petrus Staes and his wife Clementina de Maeyer were living on their farm in the Prosperpolder, at the end of the Zorgdijk against the dyke of the Koningin Emma Polder. Still living with them on the farm were their two sons and two daughters. Around noon of Thursday the 29th of June the farmer and his wife and daughter Marie José after their lunch were went outside the house to enjoy the nice weather. Daughter Agnes had gone to the village to do some shopping the two sons were working in the fields and had not come home for lunch. Shoo Shoo Baby crashed into the two barns killing the farmer and his wife on impact, the daughter was found in a hedge, seriously wounded at her head and she died hours later. The son Prudent at a nearby field witnessed this horrible fate of his family and their farm. The barns were in flames and the east part of the house was damaged. It could be repaired and today it still stands.

A deaf mute tailor on a bicycle

In Sint Niklaas Gilbert Rosseels was head of one of the local underground organizations the N.K.B. . Mr. Vos, secretary of the local hospital arranged the move of the pilots to “friendly” families. The first to transport was Charles Armour who had been staying in the local hospital. Helping allied airmen was good for a place of honour in front of a German firing squad or at best a single ticket to a deportation camp. As it was this dangerous everything had to be planned and prepared like a real military operation, and all in the utmost secrecy.

Charles Armour emerged from the hospital as a brand new man with a brand new ID card: Albert De Clerck, a tailor with a serious handicap: deaf-mute. The real handicap of this ex-USAAF pilot was that he was not able to ride a bicycle on his own. Thus the option of a tandem was used. After a trial run on the inner court of the hospital he qualified and the group took off for Zele a village some Km’s South of Sint Niklaas. The driver on the front seat of the tandem was Gilbert Rosseels, his wife, Petrus Van Doorselaere, Cyriel Van Driessche and de Waegemaker an ex commander from the army formed the group. After crossing the road Antwerp- Ghent only just on their way the bike they rode got a flat tire. Well prepared the men repaired it in less than no time. To avoid check points secondary roads were taken but after a bend at a RR crossing the group was stopped by a couple of Flemish SS soldiers looking for work dodgers. The papers were controlled but all went smooth and the deaf-mute tailor was very deaf! After the stop Carlie appeared to be very motivated and he hit the pedals in such a way that the trip started looking like an escape.(which it was in fact). On the descending road near the train station in Waasmunster a couple of German soldiers hooked on. They enjoyed the race behind the tandem very much. Had they known that they were racing an American pilot….

The group arrived at the house of Octaaf De Boever, in Langevelde near Zele. The family owned the tandem and Octaaf had a butcher’s store. The house was 120 meters from the street which made it safer for hiding. There was another person hiding: a job dodger and Charlie Armour took the place of another one that had been arrested by the Gestapo when he visited the village fair. The day Charlie arrived was Saturday 8th July 1944. On the Monday after his arrival a German truck stopped near the house. Soldiers patrolled in the village causing enormous stress in the house of De Boevere. The daughter Georgette went out on the bicycle and was reassured to see that the Germans were controlling passes in several locations and did not appear to be after a certain house. Charles followed the war by listening to the BBC, helped with peeling potatoes and looking after the animals. In the evenings they would play cards. All in all, not an unpleasant stay.

Co-pilot on a tandem

Donald Blodgett had also been moved South from the Emma Farm into Belgium: he stayed in Moerbeke at the house of Emiel De Winne. In the house were five more US Airmen hiding and Winne asked for Blodgett to be transported further down the line. They did the same trip on the tandem this time the co-pilot in the co-pilot seat. Blodgett was surprised and very glad to find Armour at the address where they were hiding from then on. Their stay was not unpleasant and they helped the lady of the house with preparing the food and other little jobs. They were liberated on September 5th by advancing Allied troops and left Zele on September 8th. They had been hiding on the same address for two months. On the 12th of September 1944 Armour and Blodgett were back in England and interrogated.