Crew 35 – Assigned 753rd Squadron – October 25, 1943

Shot down March 6, 1944 – MACR 3346

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Crew Position | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1Lt | Lloyd F Andrew | 0742046 | Pilot | Aug-44 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

| 2Lt | Robert J Slencak | 0811255 | Co-pilot | 06-Mar-44 | POW | Shot Down - w/Capt Bogusch |

| 2Lt | John P Egan | 0694863 | Navigator | 06-Mar-44 | KIA | Shot Down - w/Capt Bogusch |

| 1Lt | George Thompson | 0752910 | Bombardier | Aug-44 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

| S/Sgt | James H Musa | 18149724 | Radio Operator | 06-Mar-44 | KIA | Shot Down - w/Capt Bogusch |

| Sgt | Glen V Reiley | 13048158 | Top Turret Gunner | 06-Mar-44 | KIA | Shot Down - w/Capt Bogusch |

| Sgt | Raplh Sindelar | 3552707 | Ball Turret Gunner | 06-Mar-44 | POW | Shot Down - w/Capt Bogusch |

| S/Sgt | James l Peteete | 38206571 | Flight Engineer | 06-Mar-44 | POW | Shot Down - w/Capt Bogusch |

| Sgt | Winfred Robinson | 12199357 | Nose Turret Gunner | 06-Mar-44 | POW | Shot Down - w/Capt Bogusch |

| Sgt | James McKenzie | 32768716 | Tail Turret Gunner | 06-Mar-44 | POW | Shot Down - w/Capt Bogusch |

Lt Lloyd Andrew’s crew trained with the 458th Bomb Group at the Tonopah Bombing and Gunnery Range in Nevada in the fall of 1943. They moved overseas with the group in January 1944.

Andrew and Crew 35 participated in the 458th’s February 25th diversion mission to the Dutch Coast in support of the Eighth Air Force’s “Big Week”. The crew’s first combat mission was on March 6, 1944, the first American raid on Berlin. Due to illness, Lloyd Andrew would not make this mission. Also not a part of the crew on this day was bombardier 2Lt George Thompson. Their places were taken by Captain Jack Bogusch, 753rd Operations Officer and 2Lt Robert Swift, bombardier from Crew 22.

The 458th did not meet any German defenses until they were over Berlin. On the bomb run there was a problem with the lead ship and no bombs were dropped. Colonel Isbell, leading the group, decided upon another run and turned the formation around to come in again on the same target. The B-24’s of the 458th paid the price on this second run, as five aircraft were downed – the most lost by the group on a single mission.

Crew 35, flying in the lead squadron directly behind the first element, sustained several flak hits, but no major damage. At some point after bombs away FW-190’s attacked the formation and the crew lost power on three of their four engines. They dropped out of formation and headed down. The bailout alarm was sounded and the men began to leave.

According to the Missing Air Crew Report (MACR 3346), 2Lt Robert Slencak stated that Captain Jack L. Bogusch, “either elected to crash land and couldn’t or he didn’t have time to jump.” Slencak opened his chute on leaving the plane and hit the ground almost immediately. 2Lt Robert Swift stated that “Captain Bogusch remained at the controls attempting to get the engines started again and failed to leave the controls in sufficient time to jump because the plane was at too low of an altitude.” The B-24 crashed in the vicinity of Tubbergen, Holland with Captain Bogusch still in the cockpit.

2Lt John P. Egan, navigator, also delayed his jump until it was too late. According to Slencak, “I believe Lt Egan followed me after and jumped (I vaguely remember seeing someone leaving [from the] opposite side of the bomb bay). I found him lying under the wing of the plane, parachute on but unopened. He probably delayed pulling the ripcord for a second or two [and] in this particular instance it was fatal.” Bob Swift last saw Lt Egan, “on the catwalk between the flight deck and nose compartment. Lt Egan did not want me to open the nose wheel doors until the second [alarm] bell was sounded. I chose to slide back to the bomb bay and he followed me. I jumped from the bomb bay with, I should judge, about 8-10 seconds to spare. My parachute opened and I was on the ground. Lt Egan apparently did not have time to jump. I never heard the second bell. I was not with my regular crew the day we were shot down. Lt Egan’s crew may have had different signals than I was used to. This may be the reason he did not want me to open the nose wheel doors.”

T/Sgt James H. Musa was also last seen on the flight deck at his radio station. According to Bob Slencak, “he absolutely refused to jump”. Despite Slencak’s efforts to make him bail out, Musa remained aboard the aircraft and was killed in the crash.

Likewise S/Sgt Glen V. Reiley, top turret gunner remained aboard the aircraft and was killed in the crash. According to the MACR, he was in the bomb bay and motioned for Slencak to jump first. Slencak remembered, “his actions indicated that he would not jump until I did.” Since Slencak hit the ground almost immediately after his chute opened, it stands to reason that Reiley did not make it out in time.

The six men who parachuted and landed safely were quickly rounded up and spent the rest of the war in German POW camps, the officers to Stalag Luft I and the enlisted men to Stalag Luft IV. The four men killed in the crash were buried at the cemetery in Albergen on March 12, 1944.

1Lt Lloyd Andrew, now without a crew, flew two additional missions in March. On April 9, 1944, he took over as first pilot of Crew 36 when their pilot, 1Lt Andrew Kovich was removed from flying status. Lloyd Andrew successfully completed his combat tour in August and was awarded the DFC.

1Lt George Thompson also completed his combat tour in August, although which crew or crews he flew with is unknown.

————————-

MACR 3346

Eyewitness description… “When last sighted aircraft was on course but losing altitude slowly supported by P-47s.”

Crew 35 Missions

| DATE | TARGET | PILOT | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25-Feb-44 | DUTCH COAST | ANDREW | D2 | -- | 41-28729 | -- | J4 | D2 | UNKNOWN 046 | Diversion Mission |

| 06-Mar-44 | BERLIN/ERKNER | BOGUSCH | 4 | 1 | 41-29286 | R | J4 | 3 | UNKNOWN 011 | FLAK |

Lloyd Andrew Missions (After his crew was lost)

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26-Mar-44 | BONNIERES | 14 | 1 | 41-28671 | K | J4 | 10 | UNKNOWN 001 | |

| 27-Mar-44 | BIARRITZ | 15 | NTO | 41-28706 | J4 | -- | DREAM BOAT/SPARE PARTS | NO TAKE OFF - TIRE BLEW | |

| 09-Apr-44 | TUTOW A/F | 18 | 2 | 41-28733 | P | J4 | 11 | RHAPSODY IN JUNK | Kovich listed also?? |

| 10-Apr-44 | BOURGES A/F | 19 | 3 | 41-28733 | P | J4 | 12 | RHAPSODY IN JUNK | |

| 12-Apr-44 | OSCHERSLEBEN | REC | -- | 41-28733 | P | J4 | -- | RHAPSODY IN JUNK | RECALL |

| 22-Apr-44 | HAMM M/Y | 25 | 4 | 41-28733 | P | J4 | 17 | RHAPSODY IN JUNK | |

| 24-Apr-44 | LEIPHEIM A/F | 26 | 5 | 41-28733 | P | J4 | 18 | RHAPSODY IN JUNK | |

| 25-Apr-44 | MANNHEIM A/F | 27 | 6 | 41-28733 | P | J4 | 19 | RHAPSODY IN JUNK | |

| 27-Apr-44 | BONNIERES | 29 | 7 | 41-28733 | P | J4 | 21 | RHAPSODY IN JUNK | |

| 27-Apr-44 | BLAINVILLE-SUR-L'EAU | 30 | 8 | 41-28733 | P | J4 | 22 | RHAPSODY IN JUNK | |

| 29-Apr-44 | BERLIN | 31 | 9 | 41-28733 | P | J4 | 23 | RHAPSODY IN JUNK | |

| 01-May-44 | MARQUISE/MIMOYECQUES | 32 | 10 | 41-28705 | H | J4 | 22 | YE OLDE HELLGATE | |

| 01-May-44 | LIEGE M/Y | 33 | 11 | 41-28735 | S | J4 | 18 | UNKNOWN 005 | |

| 04-May-44 | BRUNSWICK/WAGGUM | 34 | 12 | 41-28733 | P | J4 | 24 | RHAPSODY IN JUNK | |

| 05-May-44 | SOTTEVAST | 35 | ABT | 41-28733 | P | J4 | -- | RHAPSODY IN JUNK | ABORT - #4 ENG FIRE |

| 08-May-44 | BRUNSWICK | 37 | 13 | 42-50320 | J | J4 | 8 | UNKNOWN 018 | |

| 11-May-44 | EPINAL | 39 | 14 | 42-50320 | O | J4 | 10 | UNKNOWN 018 | |

| 12-May-44 | BOHLEN | 40 | 15 | 41-28733 | P | J4 | 26 | RHAPSODY IN JUNK | |

| 13-May-44 | TUTOW A/F | 41 | 16 | 41-28733 | A | J4 | 27 | RHAPSODY IN JUNK | |

| 19-May-44 | BRUNSWICK | 42 | 17 | 42-100408 | D | J4 | 16 | LADY LUCK / THE BEAST | |

| 23-May-44 | BOURGES | 45 | 18 | 42-95120 | M | J3 | 6 | HOOKEM COW / BETTY | |

| 08-Jun-44 | UNSPECIFIED TGTS | AZ04 | -- | 42-100408 | D | J4 | -- | LADY LUCK / THE BEAST | ABANDONED - WEATHER |

| 14-Jun-44 | 5 TARGETS | AZ06 | 19 | 42-100408 | D | J4 | 17 | LADY LUCK / THE BEAST | |

| 13-Jul-44 | SAARBRUCKEN | 90 | 20 | 41-29305 | N | Z5 | 28 | I'LL BE BACK/HYPOCHONDRIAC | |

| 17-Jul-44 | 3 NO BALLS | 92 | 21 | 42-110163 | M | J4 | 9 | TIME'S A WASTIN | |

| 20-Jul-44 | EISENACH | 95 | 22 | 42-100408 | D | J4 | 20 | LADY LUCK / THE BEAST | |

| 21-Jul-44 | MUNICH | 96 | 23 | 44-40275 | L | J4 | 4 | SHACK TIME | |

| 24-Jul-44 | ST. LO AREA | 97 | 24 | 44-40201 | N | J4 | 4 | SILVER CHIEF | |

| 28-Jul-44 | LEIPHEIM & CREEL A/Fs | SCR | -- | 44-40285 | L | J4 | -- | TABLE STUFF | BRIEFED AND SCRUBBED |

| 01-Aug-44 | T.O.s FRANCE | 100 | 25 | 42-110141 | U | J4 | 7 | BREEZY LADY / MARIE / SUPERMAN | |

| 02-Aug-44 | 3 NO BALLS | 101 | 26 | 44-40285 | H | J4 | 19 | TABLE STUFF | |

| 04-Aug-44 | ACHIET A/F | 104 | 27 | 42-100431 | B | J4 | 32 | BOMB-AH-DEAR | SPEER CREW |

| 05-Aug-44 | BRUNSWICK/WAGGUM | 105 | 28 | 42-100431 | B | J4 | 33 | BOMB-AH-DEAR | SPEER CREW |

| 08-Aug-44 | CLASTRES | 108 | 29 | 42-100408 | D | J4 | 24 | LADY LUCK / THE BEAST | |

| 09-Aug-44 | SAARBRUCKEN | 109 | 30 | 42-100408 | D | J4 | 25 | LADY LUCK / THE BEAST |

2Lt Robert N. Swift – Bombardier

Some decisions mean you live or you die. Bob Swift knows the exact instant he made the right one. His B-24 bomber was a few hundred feet above the ground and dropping fast. Standing on the catwalk in an open bomb bay the afternoon of March 6,1944, he didn’t hesitate when Lt. Bob Slencak yelled through the roaring noise, “Let’s get out of here!” The day before Swift, 22, had flown on his second bombing mission, a relatively short one to Bordeaux, France. He told that to the man who awakened him because crews usually didn’t fly missions two days in a row. “That don’t make any difference,” he was told, “You’re going today too. Get up.” In the large briefing room where the aircrews of the 458th Bomber Group had gathered, the curtain covering the map showing the day’s mission was pulled aside. The red line showed they would hit Berlin. At this point in the Allied bomber offensive, that was still a dangerous mission. Only two months before had the American Eighth Air Force gained ascendancy over the Luftwaffe in Germany’s daytime skies. Swift’s crew included Capt. Jack Bogusch the squadron operations officer. The rest of the crew knew each other, but Bogusch would replace the sick pilot. Swift was substituting for the regular bombardier.

Take off from the airfield at Horsham St. Faith in southern England was early in the morning. The B-24 Liberator bombers took off with their heavy loads of bombs and fuel, then joined up with their squadrons and groups so the entire force could fly together for the continent. The flight to Berlin went smoothly, as Swift recalled: no fighters, no antiaircraft fire (flak). “We went over Berlin, made the bomb run. We didn’t drop.” In combat, Swift explained, 12 planes drop their bombs off the lead airplane. “When his bombs drop, you let yours go, so you have a pattern that hits the target down there — if you’re on the target.” The lead bombardier did not release on that first bomb run. Swift did not know why. He learned later the lead bombardier was not close to being lined up on the target, an aircraft engine factory. “So we went out, turned around and came back in again on another bomb run, which is a very, very bad thing to do, which meant two times through all that flak over Berlin.” And it was pretty thick. “What you see is a cloud that shouldn’t be there, but in that cloud what you see is red balls of fire when those things explode and spread the shrapnel. “Our plane was hit quite a few times by that flak, but no one was hurt and there was no damage insofar as we could see. … Just simply some holes.” The planes dropped their bombs on that second pass and headed back for England.

As bombardier, Swift’s station was in the nose of the bomber; where there was a turret with twin .50 cal. machine guns. With the bombs dropped, his job now was nose gunner. He had to leave the station briefly to help the navigator just behind him, Lt. Egan, who had passed out after his oxygen line froze. As he was finishing that, the call came over the plane’s intercom that fighters were attacking from one o’clock, nearly in front of them. He got back to his guns to see the FW-190s coming in. “The leading edge of their wing is just as red as it could be with fire when those 20mms are all firing like they do.” The Germans didn’t hit Swift’s plane. “The airplane flying to our right had half its tail rudder shot off, but it was all right.” It continued with the bomber formation. “The bomber on the left apparently received a direct hit of some sort and it nose-dived down.” No one saw any parachutes, but some of the crew survived and were captured. Swift had told Egan that morning that if it became necessary to get out, Swift would need Egan’s help because in a B-24 the door to the turret had to be properly lined up or it would not open. After the attack, the engines started sounding odd. Swift asked the pilot if there was trouble. Bogusch told Swift he had lost power to three of the four engines. At that point, Egan helped Swift out of the turret. Back in the bombardier/navigator compartment, Swift snapped the parachute pack to his chest harness. To bail out of the B-24, the navigator and bombardier are supposed to leave through a nose wheel door. They release the door by pulling on a little red handle. “I got down to pull the handle and Lt. Egan kept saying ‘No. No.’ And he also kept saying, ‘My poor mother. My poor mother.’ I told him to forget about his mother and worry about getting out of there. He kept telling me not to pull the red handle.” He had heard one bell, the signal for the crew to get ready to jump. A second ring means jump. Swift gave up on the nose wheel exit and headed for the bomb bay. The doors were open. That leaves a platform about 10 inches wide to walk through the bomb bay to get to the back of the airplane. Step off that platform and it’s a straight fall to the earth. When he got onto the 10-inch wide catwalk, Swift encountered the turret gunner. He had his parachute on, too, but was too scared to jump. “I tried to throw him out. I could see the ground was coming up close. I hadn’t heard the second bell, but I figured we had to be getting out of there. “I tried my best to not only talk him out but to physically throw him out. But he had his arm wrapped right around the bomb bay (stanchion.) I just could not get him out of there. Just at that time, when I was trying to throw him out, Lt. Bob Slencak, who was the copilot that day, stepped into the bomb bay.” Slencak yelled, “Let’s get out of here!” That, Swift has said over the 57 years since, saved his life.

Slencak’s words alerted Swift to the danger just seconds away. With the ground quickly getting [closer], Swift dropped out of the bomb bay, his arms folded. “As soon as my chute opened, I heard the motors’ roar.” He could tell the pilot was still in the Liberator, trying to get the motors working. Swift could see the big bomber was in a flat spin. “It wasn’t going down nose first. The wings were level with the ground and it was losing altitude very fast.” He watched the B-24 come around 125 to 130 degrees of a circle and smash into the ground. The plane hit the ground so hard the aluminum skin ripped off. He could see the bomber’s skeleton of bulkheads and ribs. He saw a brief burst of flame about eight feet high come out of the left outside engine of the downed aircraft. Because of the way the bomber hit the ground and the way the flame shot up and then went out, Swift firmly believes the bomber had run out of gasoline. “Otherwise we would have had a big, big ball of fire coming up from that airplane.” He thinks it possible that flak had cut holes in the gas tanks and it had leaked from the bomber as a vapor so that the crew couldn’t see it leaking away. Fuel tanks on American combat aircraft were self-sealing so that they wouldn’t leak when hit, but perhaps the holes were big enough so that they could not seal. All that, Swift saw in the four or five seconds it took for him to float to the ground after his parachute opened.

He and Slencak landed about 25 feet apart. “First thing he said was, ‘Boy, am I glad to see you.'” They came down in a wheat field in a farm just inside Holland. They headed for a patch of woods about 100 feet square. They buried their parachutes in the mud near a small stream. They knew they couldn’t stay in the woods too long and headed through the open field for a larger section of woods about 300 yards away. A man in a long, black coat armed with a revolver captured them. Swift learned he was a Holland Home Guard member. Perhaps he would have been killed if he had not taken the American fliers to the Germans. They were walked to the small town of Turbergen, about half a mile away. About two-dozen people walked along with them, including a male teenager about 16 or 17 who spoke fluent English. In Turbergen, they were taken to the mayor’s office, who asked them in Dutch if they were injured. They said they weren’t. They were taken to another office and later found out from a Catholic priest that four men on the bomber had died. Slencak was allowed to go to the wreckage for a Catholic burial service. He was not allowed near the plane, though. Once he was back, the two Americans gave them milk and a sandwich. It was the last food they would get for several days. After dark, a German officer took them by car to another town. As they drove up to the airfield, the German told them to look. They saw a B-17 come in for a landing. “The Germans used it. They would apparently go up and give an exact altitude to the flak gunners. They could get pretty accurate with their flak that way.” Swift and Slencak were put in a small, dark room with about 15 other fliers who had been captured that day. They were there about four days. Swift doesn’t recall getting any food the entire time. After the four days they were taken by bus to Amsterdam, a 90-minute drive, and put in cells. From there, they were taken by train to Germany….

(Written by Bill Welch and reproduced here with permission from Robert Swift)

2Lt Robert Slencak – Co-pilot

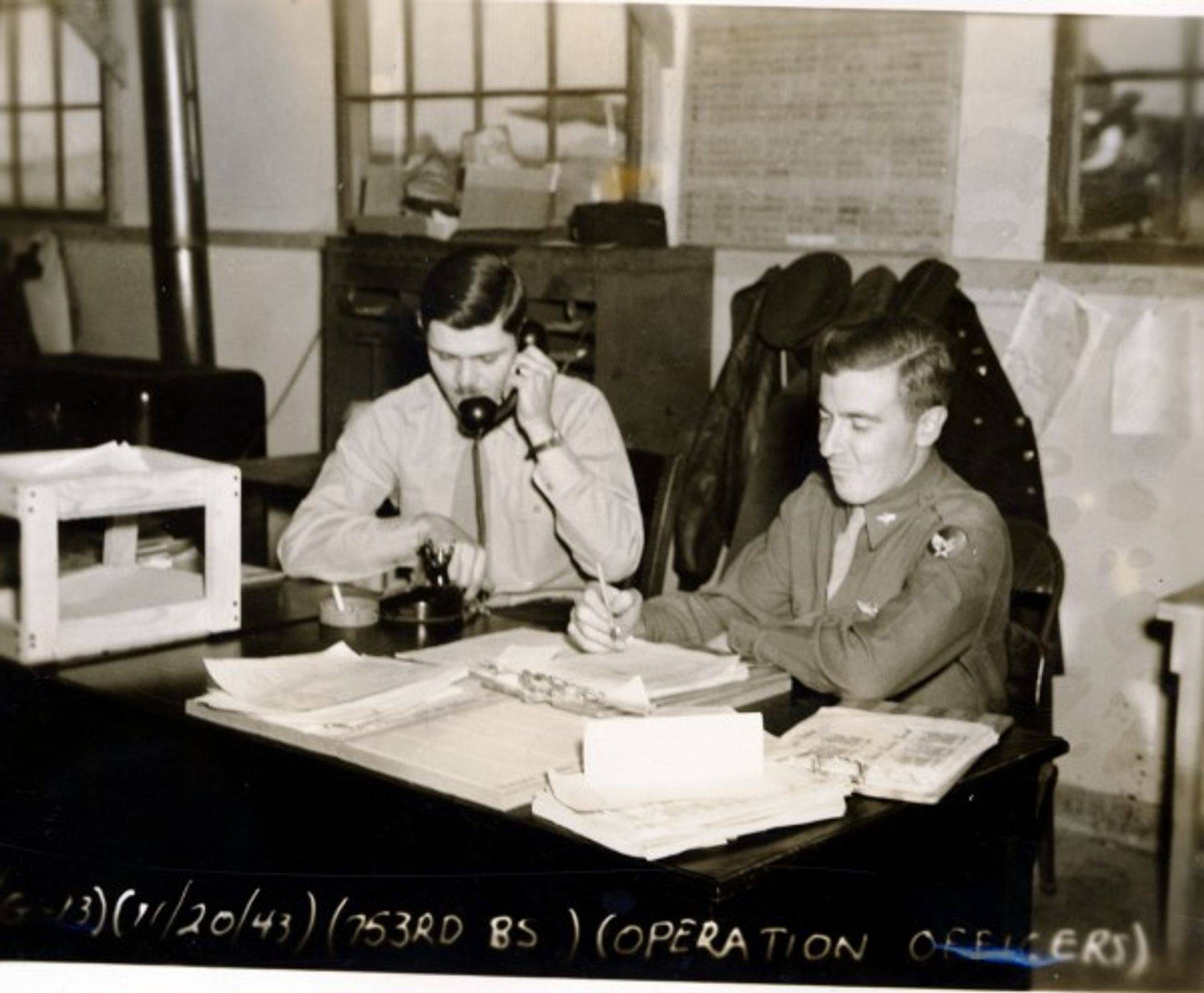

753BS Operations Officers

November 20, 1943: Capt Jack Bogusch [left] and Lt Leland Griffith during 458BG Phase III (Combat Crew) Training, Tonopah, Nevada