458th Bombardment Group (H)

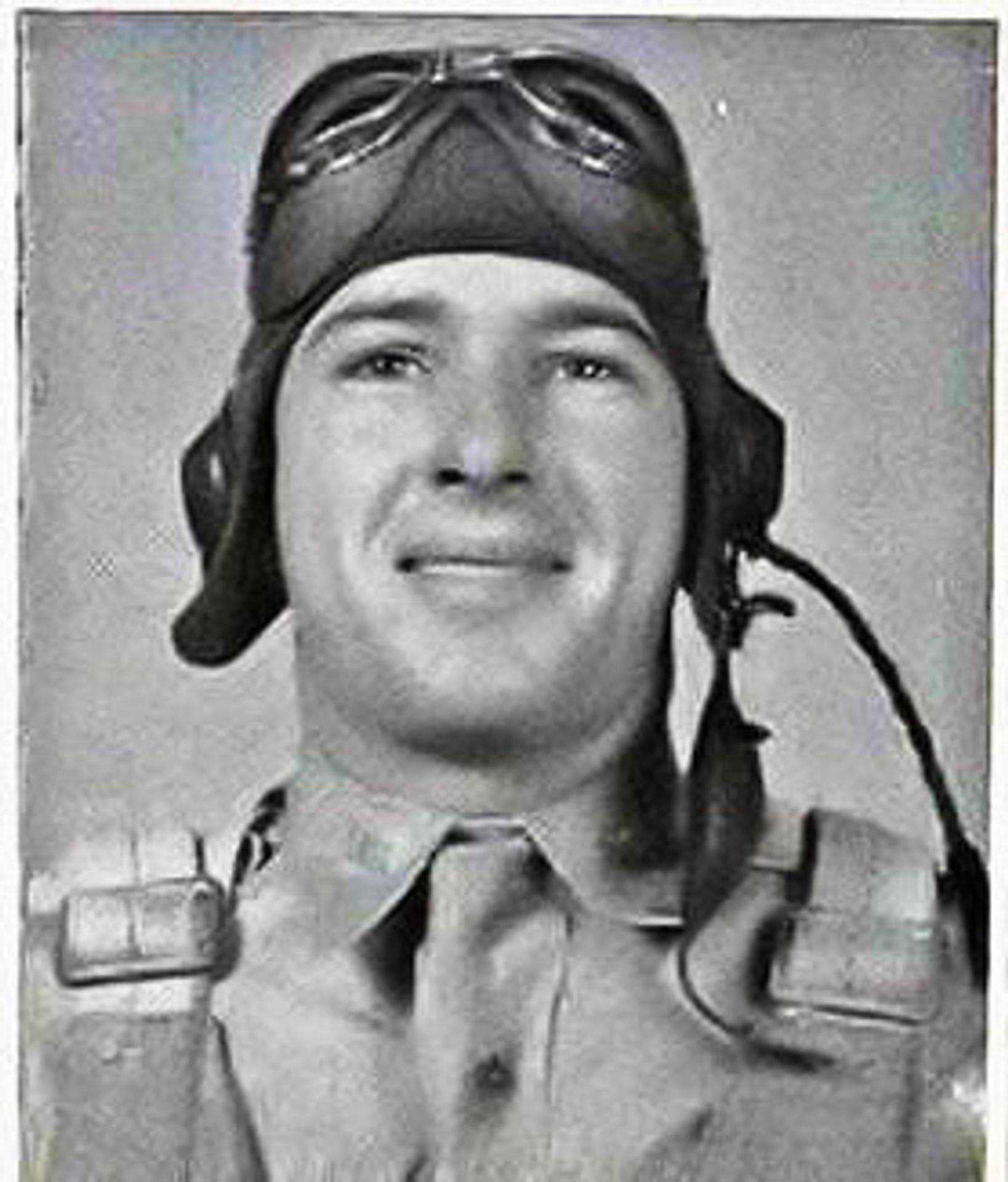

Captain Evans

CPT CHARLES S. “SAM” EVANS, B-24 LIBERATOR COMBAT PILOT, 1943-1945, Serial No. O664988[1]

[Many Thanks to C. Clarke “Jerry” Leone, a close friend of the Evans’, for compiling this information.]

Charles S. “Sam” Evans was born in Corsicana, Texas, in January 1922. His family moved to Goliad in about 1930, where he was graduated from high school. Owing to widespread unemployment during the Great Depression, at the tender age of 16 he joined the Texas National Guard based at Foster Field in Victoria, Texas. He had lied about his birth date, claiming it was 1919. Official records show that he later enlisted in the Army (serial no. 20818188) on 25 November 1940 when he was presumably 21, but was actually 18.

Not long after joining the Army, Sam saw a notice posted on a bulletin board: anyone wanting to take an examination for entry to military flying school should sign up. He did, and was sent to be tested. He was selected and then trained at the flying school at Kelly Field near San Antonio. Upon graduation, he was commissioned a Second Lieutenant and awarded his Aircrew Badge (“wings”).

After completing the school, he was transferred to Massachusetts and assigned to anti-submarine patrol, flying in twin engine aircraft. While still with that patrol, he was sent to Galveston – by this time, he was a co-pilot. He was then transferred to Bomber Command at Geiger Field in Spokane, Washington, where he remembers learning to fly B-24s. He was told that if he wanted to move from co-pilot to pilot and be assigned his own crew, he’d be sent for advanced training in B-24s at Peterson Field in Colorado Springs.

He earned his pilot’s wings at Peterson Field, where he was promoted to First Lieutenant. On 10 April 1944 in Topeka, Kansas, he was given a crew and flew a B-24 over the southern route[2] to Belfast, Ireland. He believes his orders were to land in Ireland, rather than England, in order to avoid German fighters. Thus he flew out over the Atlantic to steer clear of them, for unlike some aircraft ferried to Europe, his Liberator was alone, unaccompanied by sister ships. Once in Ireland, he and his crew travelled by sea to Scotland. He was assigned on 20 May 1944 to RAF Horsham St. Faith near Norwich near the east coast of England, about 120 miles northeast of London. There he served in the 753rd Bomb Squadron[3], 458th Bombardment Group (Heavy)[4], 96th Combat Bombardment Wing, 2nd Air Division, 8th Air Force.

Most B-24 crews were staunch defenders of the Liberator, and took offense if they sensed a hint that someone thought the B-17 Flying Fortress was superior. B-17 crews called the 24s “the crates the 17s came in”. Another epithet was “flying boxcar”. Sam’s response to a comparison of the two aircraft is, however, sanguine. He had flown once – as an observer – in a B-17 when on submarine patrol in Massachusetts, and calls it “a fine plane”. He does not rate one above the other, saying that each had its own advantages and disadvantages.

Between June 1944 and February 1945 while stationed at Horsham St. Faith, Sam flew 30 combat sorties (and was advanced to Captain sometime after 23 October 1944). Throughout these nine months the 458th BG operated primarily over Germany, hitting targets such as industrial areas; oil refineries; aircraft engine factories; fuel depots; canals; airfields; and railroad marshalling yards. The Group carried out support operations in addition to those strategic missions. It helped prepare for the invasion of Normandy by striking gun batteries, V-1 flying bomb and V-2 rocket sites, and airfields in France. After D-Day (6 June 1944) it bombed bridges and highways to prevent the movement of enemy materiel to the beachhead. It attacked enemy troops to aid the Allied breakthrough at St. Lo in July. During September, it hauled gasoline to airfields in France. It struck Nazi transportation lines during the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944 and January 1945.

The 458th BG arrived in England in January 1944. It completed 240 missions[5], the first one in February 1944 and the last one in April 1945. To date, records reveal that over 5,500 named personnel served in the 458th and its sub-units[6]. Of those, nearly 592 combatants (pilots and crew members) were killed in action (252); interned by a neutral country (60); evaded capture (34); captured as prisoners of war (193); and died in non-battle accidents (53)[7]. Of the 300 or so B-24s that were assigned to the 458th[8]; at least 71 were lost[9].

Sam believes he was dealt a lucky hand. He recalled that while on missions, he and his crew did not encounter some of the more common, but often fatal, problems caused by fog and icing, or with malfunctions of bomb racks, bomb bay doors, the electrically heated flying suits or oxygen masks.

One of the most astonishing details he disclosed is that he rarely turned the controls over to his co-pilot. When he did, it was most often during the return flight to England, and then for only very short periods of time. Missions could consume 10 or more hours of flying time. B-24s had heavy controls requiring muscle to manipulate. Sam must have expended an extraordinary amount of energy, possessed remarkable concentration and strength, and endured enormous stress.

They hailed from Kansas, Maryland, Iowa, Florida, Massachusetts, West Virginia and Oregon. Two were from Illinois. They were a shipping clerk, a laborer in a coal mine, a logger, a stock boy at a retail clothing store, a budding musician who played piano and clarinet in his high school band, a section hand on the railroad, and an inspector at the Cessna Aircraft Co. Two were farm boys. One would soon lose his brother, killed in the South Pacific theater. The oldest was 33, the youngest, 19 (Sam himself was 22). Two were family men; one, a girl-chaser. They were Sam’s combat crew: 1LT Frederick A. Johnson, co-pilot (1923-?); 1LT George Frederick Adkins (1920-2003), bombardier; 2LT Walter Meylan Cline (1921-2004), navigator; T/SGT Max Kenneth Van Buren (1911-1961), airplane mechanic-gunner (crew chief); T/SGT Leon Charles Huggard (1922-2004), radio operator-mechanic-gunner; S/SGT Donald Richard Conway (1923-2000), airplane mechanic-gunner; S/SGT Lawrence Richard Matson (1916-1966), airplane armorer-waist gunner; S/SGT James Alburn Michaelson (1919-1966), aerial gunner; and S/SGT Darrell Ward Latch (1924-1997), aerial gunner[10].

Sam completed the then-required number of missions in late January 1945 and was transferred to the 70th Replacement Depot in February. Thus he was in England for about 10 months. His 30 combat flights consumed at least eight of those months. Many pilots completed their 30 missions in less time. The reason is explained by Darin Scorza, the leading authority on the 458th BG and a co-author of LIBERATORS, in an e-mail dated 25 September 2015 to the author:

“Lead crews did not fly as often as the other wing (non-lead) crews in the group. [During] . . . the period prior to [the Evans Crew] becoming a lead crew, roughly June thru August, they flew 2-3 missions a week, sometimes more. After becoming a lead crew the amount of times they would fly a mission is cut drastically, maybe only 2-3 times per month. There was a whole squadron of lead crews to choose from each day, where you might have the need for four maybe six leads vs. twenty or so wing crews. So the rotation on lead crews was definitely long in between. They were constantly training though, on these off days, in the air and on the ground. This was a factor in a few of the cases that I have heard of crews either becoming a lead or not. Many opted to remain where they were in order to finish up quickly and go home.”

Thereafter Sam piloted a B-24 back to the states, again on the southern route. As was the case when he flew from the U.S. to Europe many months earlier, he was not in the company of other aircraft – his Liberator was alone on the flight home. None of the 15 to 20 so men going home with him were his original crew members, for they did not complete their 30 missions at the same time.

Sam said he had no navigator aboard; he did his own navigating. And, as was the case during his combat missions, he had the controls almost all the time, rarely turning them over to the co-pilot, because he “wanted to make certain we got home.”

The returning flyboys were not the only homeward-bound passengers.

While stationed at Horsham St. Faith, Sam had met an Oregonian named Carey Rockey, also stationed there, a Second Lieutenant WAC with the 96th Combat Bombardment Wing (the story of her military service accompanies this). She became his bride-to-be. An animal lover, she bought a purebred English Springer Spaniel, of championship bloodlines, for $300 from a nurse living in the same barracks as Carey (by that time, Carey had been transferred to RAF Burtonwood in western England). The nurse was unable to care for Sissy properly because of her long work hours. Carey convinced Sam to sneak Sissy aboard as a stowaway to the states.

Carey, with Sissy in tow, met Sam at RAF Lichfield (also called Fradley Aerodrome) in Staffordshire where he was assigned a B-24 to fly home. There were no pet carriers in those days – Sam had to fling Sissy onto the plane, into the waiting arms of a co-conspirator passenger, and hope that no one in authority was watching.

During an interim stop in Dakar, Sissy found a mate of her own. Sam thoughtfully delivered a very pregnant Sissy in the B-24 to Carey’s father, whom he met for the first time, at the airport in Portland, Oregon[11]. Sam then flew on to Geiger Field in Spokane, Washington.

Sam is one of those World War II veterans who rarely spoke of his service, and saved nothing – records, awards and decorations, photos or letters. Nor did he keep a diary, mission log or journal. Carey said he wished to leave his memories of combat behind him. Nevertheless, he did remain in the Air Force Reserve for nearly 10 years. Carey herself took flying lessons in Portland after her discharge but before their marriage, even soloing in a Piper Cub. When Sam found out, he insisted she stop with the lessons because flying, he said, was too dangerous.

Sam had completed one year of college (1939-1940) at the University of Texas, San Antonio, during his two years in the Texas National Guard. Upon his discharge from the Army, he returned for another year at the University of Texas. After Carey’s discharge in 1946, they were married and then both attended the University of California at Berkeley. When they obtained their degrees they moved to her hometown. In 1958 Sam earned a law degree from Northwestern School of Law in Portland. He practiced until retiring in 2011. Sam died on 31 December 2016; Carey still resides in Portland.

Although he said that luck was with him, on a number of bombing missions the aileron cables were severed by anti-aircraft flak or gunfire from German fighter planes, and Sam had to take his time getting back to England because he could make only wide turns. There were, though, two especially harrowing incidents recounted below.

A Mission and a War Story

The beefy lines of that inelegant workhorse, the snout-nosed B-24 heavy bomber

[B-24JAZ-95-CO42-100341 J4 A Satan’s Mate of the 753rd Squadron]

The first event occurred on 20 July 1944 when returning from a bomb run over Eisenach in central Germany[12]. “We hit a lot of air turbulence on the mission and used up most of our fuel. When we were landing, the nose wheel would not go down. Because most of our fuel was used up, we had only one chance to land successfully. A plane was landing on the emergency strip just before us and we were given the signal to go around but I knew there was no fuel to do that. I thought the other plane was off the runway far enough, so I ignored the order to go around.

“I had the crew all run to the back of the airplane so their weight and my flying could keep the nose of the airplane up till the last second as we slowed down on the runway. I feathered the port engine because there wasn’t any fuel for it. I told one of the crew to attach a parachute to the plane and toss it out so it would open up just as the wheels touched the runway because I couldn’t use the plane’s brakes. That would cause the plane’s nose to hit the runway.

“I landed it so that the nose stayed off the ground until the very last second. The emergency truck arrived just about the time when the plane came to its final stop and as the nose gently touched the ground. My crew had to hold back my angry co-pilot as the ground crew officer yelled at me, ‘Why didn’t you wait for me to put a box under the nose before you put the nose down!’

“I had to answer for ignoring the signal to go around. I told the reviewing officer that I had no more fuel left and would have crashed if I tried to pull up: ‘I chose life for my crew.’ There was some grumbling but I never heard anything more about that.[13]“

Epilogue: The flight engineer/top turret gunner aboard HOWLING BANSHEE was in the same formation but a different squadron[14]. He kept a diary of his days at Horsham St. Faith. It has the following entry for July 20, 1944:

July 20 – M7 Target was an airplane plant near Eisenach, south of Leipzig. We hit an alternate target, a marshaling yard, in a little town about 20 miles northeast of the primary target. Quite a bit of flak. Some of the planes did not drop their bombs on the alternate, so we went to another target northwest of the primary. The flak was very accurate there. Planes were jinking all over the sky. I got several pictures, but it is difficult to take good pictures from the crowded upper turret. The raid took 7½ hours. Three of our planes were badly shot up. Evans’ plane landed with a collapsed nosewheel. Sparkman has refused to fly any more and Cowal [Kowal] was grounded on mental grounds[15].

Another Mission, Another War Story

August 18, 1944, was a beautiful, clear day over France[16]. The Allied forces pushed inland to near Paris, and the war was going well. Bombers of the 458th Bomb Group were on a mission to Metz[17], with the initial point (I.P.)[18] of the bomb run over Verdun. Our crew, flying the B-24 Liberator A DOG’S LIFE with CPT Sam Evans as pilot, was leading the high right squadron at 21,000 feet. No flak, no fighters, an ideal mission.

That ideal mission suddenly became a disaster. As we turned on the I.P., we encountered severe turbulence, prop wash from the squadrons preceding us. That turbulence bounced the aircraft violently, flattening us out from our turn. At the same moment, and while at 20,000 feet, our deputy lead[19] smashed into our right wing tip, stripping 11’ from the wing, and leaving it dangling in the wind.[20]

The drag of that broken wing sent us into a diving right turn. Somehow, the deputy lead slid under us, so close that I could have reached out and shaken hands with the top gunner. Fortunately, no actual contact was made. We continued in our diving turn, dropping 6,000 feet in one 360 degree turn (pretty close to a spin, yes?).

As we continued to nose dive, the following conversation was heard on the intercom – “Evans, have you got it?” No answer.

Again, “Evans, have you got it?” Again, no answer.

“Evans, have you got it? If you won’t answer me, I’m getting out of here.”[21]

Finally, a slow Texas drawl came back – “Ah’ve got it,” and sure enough he did.

We straightened out at 15,000 feet, continuing to drop, but at least flying again.

Our bombs were still on board, of course, so we started to find a place to unload them. We could not make a left turn to hit a rail yard ahead, so we found a convenient forest to drop them in.

Meanwhile, our Command Pilot and squadron leader, MAJ Robert H. Hinckley, Jr. (who was sitting in the co-pilot’s seat), was trying to get fighter escort for us. Flight Engineer S/SGT Donald R. Conway said, “We were all alone and rather fearful of Nazi bandits picking us off.” It seemed an eternity, but it was only a few minutes before we had a P-51 sitting on each wingtip. Don’t try to tell any of us that the P-51 isn’t the most beautiful airplane ever built!

The navigator [Walt Cline] was laying a course for Allied lines. According to our briefed information, Paris was still in Nazi hands. Our escort pilots assured us, however, that they had been flying over Paris all day without seeing any flak, so we altered course to go that way – but our course took us close to Le Havre, and there were a few anxious moments when flak started coming up from there.

We really were not in a position to take any evasive action. With climb power on engines 3 and 4, with full left rudder trim cranked in, we could maintain straight and level flight at 153 mph indicated airspeed. When power was reduced to reduce the strain on the two engines, we found our stall speed to be 148 mph. That wasn’t very comforting. The fastest we could fly was 153 mph because of the damage, and if CPT Evans flew below 148 mph, our plane would drop from the sky for lack of lift over the wings.

Eventually we reached England, and proceeded to the crash strip at RAF Woodbridge (about 40 miles south of Horsham St. Faith) which had a 10,000-foot runway. There, life became a bit more complicated again. Out of necessity we flew a right hand pattern, and when we turned final, the right wing simply refused to come up. There we were, descending to touchdown, unable to fly level. But there was no chance of going around. We were committed.

Finally, as Evans flared, preparatory to touchdown, the wings reluctantly leveled, and we were down and rolling. We were a much relieved crew, and a very thankful one for the skill of CPT Evans.

The leading edge spar of the wing had remained intact, and from the front of the airplane it looked as though we had lost only a foot or two of wing. As we in the front section exited the aircraft, one by one we looked up to see the damage, and then our eyes slowly followed the damaged wing section down to its end. The wing was nearly broken off, almost touching the ground about 18 inches from the tarmac.

That shock added the cap to our climax of excitement for the day.

Said CPT Evans, “I wasn’t a hero. I had a job to do and I did it.”

Epilogue: The Shannon Diary contains the following entry for 18 August 1944:

Aug. 18 – M18 We are beginning to count them now [missions – this was mission no. 18 for the diarist]. Target was an aircraft engine works at Metze [Metz], France. The initial point of our bomb run was Nerddun [Verdun]. I will bet that my Uncle Clarence would remember many of these names. We went the long way, down south of Paris. The “Howling Banshee” behaved pretty well – only one amplifier went out. On the bomb run 3 minutes from the target, two of the lead planes got into prop wash and collided. They peeled off together with wings locked. After dropping about 1000 ft., they broke free and one came back almost undamaged. The other lost about 9 ft. of wing and began its long limp home. I listened on VHF and heard them calling “Little Friend, where are you? We need escort bad.”[22] They gave their position and the fighters were called back and came up to them. We hit the targets well and were alerted to “Bandits in the Area”. We saw no Bandits and little flak. Flight time was 8¼ hrs. The damage[d] plane, which was Evans’ crew, landed OK in England.

From the diary of a different crewman in the first squadron of the formation: “lead–planes collided in back 8’ wing gone”.[23]

Moreover, the 96th Combat Bombardment Wing, headquartered at Horsham and home of the 458th’s Little Friends, noted that “[1] A/C [aircraft] did not attack for the following reasons: . . . wings damaged in collision when plane was caught in prop wash”.[24]

The “Tactical Bombing Report of Mission, 18 August 1944” contains the following notation:

One Squadron of the 458th Group attacked an A/F [airfield] south of Metz as a target of opportunity when the lead and deputy lead collided on the bomb run into the primary [target]. As a result of the collision the formation was scattered and was headed away from the target. It was not possible to make a second run so the [airfield] north of Metz was attacked.[25]

The aircraft that hit A DOG’S LIFE was DOROTHY KAY SPECIAL piloted by 2LT Harold B. Dane, the deputy lead of the second squadron and flying behind A DOG’S LIFE’s starboard wing. The nose turret gunner in DOROTHY KAY SPECIAL wrote in his Mission List: “Mid-air collision with lead aircraft which made emergency landing. Took over and led formation over target, accomplishing mission.”[26] (While the squadron did not bomb the primary target, it did bomb a target of opportunity.)

CPT Evans earned his first Distinguished Flying Cross for his actions:

Captain Charles S. Evans, O-664988, Captain, Army Air Forces, United States Army.

For extraordinary achievement, while serving as Pilot of a B-24 aircraft on a bombing mission over enemy occupied territory, 18 August 1944. Captain Evans’ aircraft collided with another B-24 at the I.P. causing ten feet of the right wing to hang vertically. After losing 5,000 feet of altitude, Captain Evans successfully bombed a target of opportunity and returned to his home base where he landed the aircraft without further damage or injury to crew. The remarkable flying skill, sound judgment and tenacity of purpose displayed by Captain Evans on this occasion reflect the highest credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of United States. Entered military service from Texas.[27]

B-24 Liberators of the 458th BG with a close escort of “Little Friends”, P-51 Mustangs, in the summer of 1944. Aircraft of the 458th characteristically had fire-engine-red ovals (the outside rudders on the tail) with a white vertical stripe in the middle. The large letter/number grouping between the tail and the waist designates the squadron (753rd squadron = J4, for example)

CPT Evans, like the others who served during this war, gave his all. He was recognized in several ways. He and his crew were assigned AZON-equipped aircraft and flew on AZON missions, even though they had not been trained with the original AZON crews at Horsham. His excellent skills as a pilot earned him and his crew a transfer to the 755th Squadron that flew lead on bombing missions. And he was twice the recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross, the award for heroism or extraordinary achievement while participating in an aerial flight. He also received the Air Medal with four oak leaf clusters, among other decorations, for having flown the required 30 combat missions.

CPT Evans attended two reunions, one of the 2nd Air Division held at Hilton Head, South Carolina, in November 1989; the other at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, in 1994[28]. They are standing beside a restored B-24 owned by The Collings Foundation. Walt Cline had insisted that the four take a look at where Sam’s name was stenciled on the Liberator.

(L-R) Unknown, Sam Evans, Unknown, Walt Cline

Notes

1 By C. Clark Leone, © 2017.

2 The flight took them from Topeka to Miami; then to San Juan, Puerto Rico; on to either or both Belem and Natal, Brazil; next to Dakar, Senegal (then part of French West Africa; this leg took about 11 hours); onward to Marrakesh, Morocco, a 7-hour flight; and finally to Ireland, about a 10-hour trip. The flight hours are from another pilot’s memoirs, (Sept. 2015).

3 On 24 October 1944, he and his crew were transferred to the 755th Bomb Squadron, which became the 458th BG’s lead Squadron. All lead crews were transferred into the 755th, while the non-lead, or “wing”, crews were moved to the other three Squadrons (752nd, 753rd and 754th).

4 For the history of the 458th BG, see Mackay, R., et al., LIBERATORS OVER NORWICH, The 458th Bomb Group (H), 8th USAAF at Horsham St. Faith 1944-1945 (Schiffer Pub., Ltd., 2010) [LIBERATORS]; https://458bg.com/ (Jun. 2015); and http://www.8thafhs.org/bomber/458bg.htm (Jun. 2015).

5 The crews flew 5,759 sorties, www.heritageleague.org/files/2012iii-Fall-Winter.pdf at p. 71 (Dec. 2015). Technically speaking, a sortie is a combat flight of a single aircraft, starting when it takes off and ending when it returns. One mission involving 12 aircraft equals 12 sorties.

6 Personnel List (Sept. 2015).

7 Casualties (Jan. 2016).

8 Group Aircraft (Sept. 2015).

9 458th Aircraft Losses (Oct. 2015).

10 S/SGT Carl Vernon White (1924-1997) from Kentucky, aerial gunner, was an original crew member. He evidently misbehaved in early October 1944, was reduced in rank to private, and removed from the crew. He was reclassified twice in February 1945: once as a Telephone Operator, and once as a Munitions Worker. In April he was transferred for Infantry Training (Feb. 2015).

11 Carey was not anxious to reveal this story because of a kerfuffle that had occurred in the summer of 1944 between the Republicans and President Franklin Roosevelt. Republicans charged that FDR, during a tour of the Aleutian Islands in Alaska, accidentally left behind his dog Fala, and that FDR sent a Navy destroyer to retrieve him, at tremendous cost to taxpayers. The charge was untrue, and the President’s “Fala speech” of 9 September 1944 put the issue to rest in a very humorous way. Thus Carey was quite nervous about asking Sam to export Sissy, and she remains slightly uncomfortable about it to this day. Sissy, however, was not the first dog to travel from England to the states in a B-24. A navigator and a bombardier on another 458th BG crew accomplished the same task in the summer of 1944 when they flew home (Sept. 2015).

12 This was combat mission no. 7, see p. 15, infra.

13 This photo of the stricken plane and its crew was taken upon their return from the Eisenach mission. The photo appears in LIBERATORS, see fn 4, supra. LIBERATORS notes that the nose gears on B-24s were a constant source of trouble. While with the 458th BG, BREEZY LADY was modified to be part of the AZON (radio controlled bomb) project. Members of the 753rd Squadron underwent training and flew only AZON missions during May and June 1944 (they did not fly in regular combat missions). Ten AZON missions were flown, and another six were briefed but later scrubbed or abandoned. CPT Evans was not one of the original trainees, although he was assigned to a number of AZON missions. The AZON project was terminated in September 1944, (Aug. 2015)

14 458BG Mission 95 – July 20, 1944 (Oct. 2015).

15 Combat Diary of T/SGT Donald R. Shannon, (Aug. 2015) [Shannon Diary]. S/SGT Leonard W. Sparkman, flight engineer on yet another aircraft, was removed from flying status that month. The circumstances prompting SGT Shannon’s remark about S/SGT Stanley A. Kowal, radio operator on the same aircraft as Sparkman, are not known. Like S/SGT Carl White who left CPT Evans’ crew, both Sparkman and Kowal were reduced in rank to private and reclassified to ground jobs, (See McCormick Crew).

16 This section, written by 2LT Walter M. Cline, was edited by C. Clark Leone. LT Cline was CPT Evans’ navigator. It is not known when LT Cline wrote this account; he died in May 2004 at age 83. The two remained lifelong friends.

17 This was CPT Evans’ 15th combat mission, see p. 19, infra; he flew the lead plane of the second squadron.

18 The starting point of the bomb run. On a combat mission, the formation flew not directly to the target, but to a chosen landmark that was perhaps 30 or so miles from the target. Upon reaching the landmark (the “initial point”), the lead plane of the lead squadron would turn toward the target. The entire formation then flew straight and level to the target – no evasive action could be taken, despite the presence of flak or enemy fighters – until the bombs were dropped. The bomb run, taking from less than one and up to 10 minutes, was usually the most dangerous and terrifying leg of a combat mission.

19 In addition to the crew, the deputy lead plane carried a Deputy Lead Pilot. This aircraft followed behind and off the wing of the lead plane (which carried the Command Pilot), and took over if the lead plane dropped out of the formation.

20 This is the event that Carey Rockey Evans mentions in her account.

21 He means that he would bail out and parachute to the ground.

22 When in radio contact, bomber crews called their P-51 Mustang fighter escorts “Little Friends” – the bombers were “Big Friends”. “Bandits” were enemy aircraft.

23 Mission Logbook & Calendar of T/SGT Lewis E. Roberts (radio operator aboard PRINCESS PAT), (Sept. 2015) [Roberts Mission Log]. PRINCESS PAT, in the first squadron, was just ahead of A DOG’S LIFE on August 18, 1944 LIFE, (Sept. 2015). In fact, 11 feet, or over one-half, of the wing was nearly broken off.

24 96CBW History – August 1944 (Sept. 2015).

25 458BG Mission 116 – August 18, 1944 (Sept. 2015).

26 Ibid.; Harold Dane Crew (Sept. 2015).

27 Headquarters 2d Air Division, APO 558, General Order No. 26, p. 2 (17 Jan. 1945)

28 Sam died 31 December 2016, 17 days short of his 95th birthday. He was the last of his crew.