Walker Crew – Assigned 752nd Squadron – May 11, 1944

Crew Photo Needed

Completed Tour

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Pos | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1Lt | Harold A Walker | 01995806 | Pilot | Sep-44 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

| 1Lt | James O Applewhite | 0705095 | Co-pilot | Sep-44 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

| 1Lt | Theodore E Joiner, Jr | 0712576 | Navigator | Jan-45 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

| 1Lt | Thomas C Blisard | 0703425 | Bombardier | Jan-45 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

| T/Sgt | Thomas L Rankin | 39126769 | Radio Operator | Sep-44 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

| T/Sgt | George E Bayuzick, Jr | 13109804 | Flight Engineer | Sep-44 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

| S/Sgt | Asa L Compton | 34800365 | Aerial Gunner/2E | 01-Jul-44 | CT | Promoted to S/Sgt |

| S/Sgt | Robert E Herman | 36459101 | Aerial Gunner/2E | 06-Jul-44 | WIA | Awards - Purple Heart (GO119) |

| S/Sgt | Robert L Johnson | 35536789 | Aerial Gunner/2E | 01-Nov-44 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

| S/Sgt | Louis H Wallace | 33228069 | Armorer-Gunner | 01-Nov-44 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

F/O Harold A. Walker and crew were a replacement crew coming to Horsham in May 1944. They flew their first mission at the end of May and their last near the end of October. The crew flew no fewer than 14 different group Liberators during their combat flying. the crew were forced to abort on four occasions, once due to weather and three times to mechanical difficulties. Their most harrowing mission was the June 24th raid on an airfield near St. Omer, France where they suffered severe battle damage and at least one gunner wounded. (See story below)

Towards the end of their tour, the crew participated in the Truckin’ missions, flying gasoline to Patton’s Army in France. Utilizing war weary Liberators from several bomb groups, and usually with a crew of six, these flights were considered (by the flyers) more dangerous than combat, due to the amount of fuel on board each flight. Walker flew seven of these low level gas hauls in September.

Currently no crew photo is available, but some group photos of the officers and enlisted men are displayed on this page.

Missions

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27-May-44 | NEUNKIRCHEN | 48 | 1 | 41-29489 | I | J4 | 7 | UNKNOWN 014 | |

| 28-May-44 | ZEITZ | 49 | 2 | 41-29489 | T | 7V | 8 | UNKNOWN 014 | |

| 29-May-44 | TUTOW A/F | 50 | 3 | 42-50314 | L | 7V | 13 | ETO PLAYHOUSE | |

| 30-May-44 | ZWISCHENAHN A/F | 51 | 4 | 41-29489 | T | 7V | 9 | UNKNOWN 014 | |

| 02-Jun-44 | STELLA/PLAGE | 53 | 5 | 42-95219 | N | -- | 10 | PATCHIE | |

| 06-Jun-44 | VILLERS BOCAGE | 57 | 6 | 41-28721 | V | 7V | 26 | DOWNWIND LEG | |

| 11-Jun-44 | BEAUVAIS | 63 | ABT | 42-100365 | B | 7V | -- | WOLFGANG | WEATHER - DepLead |

| 14-Jun-44 | DOMLEGER | 65 | 7 | 42-95118 | E | 7V | 2 | ALFRED V | |

| 20-Jun-44 | OSTERMOOR | 73 | 8 | 42-51110 | P | 7V | 14 | TOP O' THE MARK | MSN #1 |

| 20-Jun-44 | NOBALL FRANCE | REC | -- | 41-28721 | V | 7V | -- | DOWNWIND LEG | MSN #3 RECALL |

| 24-Jun-44 | ST OMER | 79 | 9 | 42-95219 | W | 7V | -- | PATCHIE | MSN #3 - MANSTON |

| 28-Jun-44 | SAARBRUCKEN | 81 | 10 | 41-29340 | N | 7V | 30 | YANKEE BUZZ BOMB | |

| 02-Jul-44 | COUBRONNE | 83 | 11 | 41-29340 | N | 7V | 32 | YANKEE BUZZ BOMB | |

| 05-Jul-44 | LE COULET, BEL A/F | 84 | ABT | 41-29352 | K | 7V | -- | WOLVE'S LAIR | #2, 4 SUPER CHGRs |

| 06-Jul-44 | KIEL | 85 | 12 | 41-29340 | N | 7V | 34 | YANKEE BUZZ BOMB | |

| 07-Jul-44 | LUTZKENDORF | 86 | 13 | 42-52455 | O | 7V | 41 | PLUTOCRAT | |

| 08-Jul-44 | ANIZY, FRANCE | 87 | 14 | 41-28721 | V | 7V | 38 | DOWNWIND LEG | |

| 13-Jul-44 | SAARBRUCKEN | 90 | ABT | 41-29303 | H | Z5 | -- | LIBERTY LIB | #2 GEN/SUPER CHGR |

| 16-Jul-44 | SAARBRUCKEN | 91 | 15 | 42-52457 | Q | 7V | 40 | FINAL APPROACH | |

| 20-Jul-44 | EISENACH | 95 | 16 | 42-50314 | I | 7V | 37 | ETO PLAYHOUSE | |

| 21-Jul-44 | MUNICH | 96 | 17 | 41-29352 | K | 7V | 39 | WOLVE'S LAIR | |

| 24-Jul-44 | ST. LO AREA | 97 | 18 | 42-50314 | L | 7V | 39 | ETO PLAYHOUSE | |

| 25-Jul-44 | ST. LO AREA "B" | 98 | 19 | 41-29340 | N | 7V | 40 | YANKEE BUZZ BOMB | |

| 31-Jul-44 | LUDWIGSHAFEN | 99 | 20 | 42-50314 | L | 7V | 40 | ETO PLAYHOUSE | |

| 01-Aug-44 | T.O.s FRANCE | 100 | 21 | 42-50314 | L | 7V | 41 | ETO PLAYHOUSE | |

| 04-Aug-44 | ROSTOCK | 103 | 22 | 41-29303 | H | Z5 | 35 | LIBERTY LIB | |

| 05-Aug-44 | BRUNSWICK/WAGGUM | 105 | 23 | 42-50314 | L | 7V | 42 | ETO PLAYHOUSE | |

| 07-Aug-44 | GHENT | 107 | 24 | 42-95219 | W | 7V | 22 | PATCHIE | |

| 09-Aug-44 | SAARBRUCKEN | 109 | 25 | 42-95179 | X | 7V | 33 | HERE I GO AGAIN | |

| 11-Aug-44 | STRASBOURG | 110 | 26 | 42-50314 | L | 7V | 46 | ETO PLAYHOUSE | |

| 14-Aug-44 | DOLE/TAVAUX | 113 | ABT | 42-95219 | W | 7V | -- | PATCHIE | #1 ENG LOSING OIL |

| 01-Sep-44 | PFAFFENHOFFEN | ABN | -- | 42-95219 | W | 7V | -- | PATCHIE | ABANDONED |

| 05-Sep-44 | KARLSRUHE | 122 | 27 | 42-50314 | L | 7V | 52 | ETO PLAYHOUSE | |

| 08-Sep-44 | KARLSRUHE | 123 | 28 | 42-50314 | L | 7V | 53 | ETO PLAYHOUSE | |

| 09-Sep-44 | MAINZ | 124 | 29 | 42-50314 | L | 7V | 54 | ETO PLAYHOUSE | |

| 10-Sep-44 | ULM M/Y | 125 | 30 | 42-100311 | P | 7V | 50 | YOKUM BOY | |

| 11-Sep-44 | MAGDEBURG | 126 | 31 | 42-52455 | O | 7V | 59 | PLUTOCRAT | |

| 19-Sep-44 | HSF to CLASTRES | TR03 | -- | 41-29577 | E | 466BG | T2 | THE RUTH E-K | RCL -W |

| 25-Sep-44 | HSF to LILLE | TR08-1 | -- | 42-52455 | O | J4 | T5 | PLUTOCRAT | 1ST FLIGHT - CARGO |

| 25-Sep-44 | HSF to LILLE | TR08-2 | -- | 42-52455 | O | 753 | T6 | PLUTOCRAT | 2ND FLIGHT - CARGO |

| 26-Sep-44 | HSF to LILLE | TR09 | -- | 42-52455 | O | 753 | T7 | PLUTOCRAT | TRUCKIN' MISSION |

| 28-Sep-44 | HSF to LILLE | TR11 | -- | 42-52455 | O | 753 | T9 | PLUTOCRAT | TRUCKIN' MISSION |

| 29-Sep-44 | HSF to LILLE | TR12 | -- | 41-29303 | H | 752 | T11 | LIBERTY LIB | TRUCKIN' MISSION |

| 30-Sep-44 | HSF to LILLE | TR13 | -- | 42-95219 | W | 752 | T11 | PATCHIE | NO DEL - FEATHER #3 |

| 14-Oct-44 | COLOGNE | 133 | 32 | 42-100311 | P | 7V | 53 | YOKUM BOY | |

| 17-Oct-44 | COLOGNE | 135 | 33 | 42-52457 | Q | 7V | 61 | FINAL APPROACH | |

| 22-Oct-44 | HAMM | 137 | 34 | 42-52457 | Q | 7V | 63 | FINAL APPROACH |

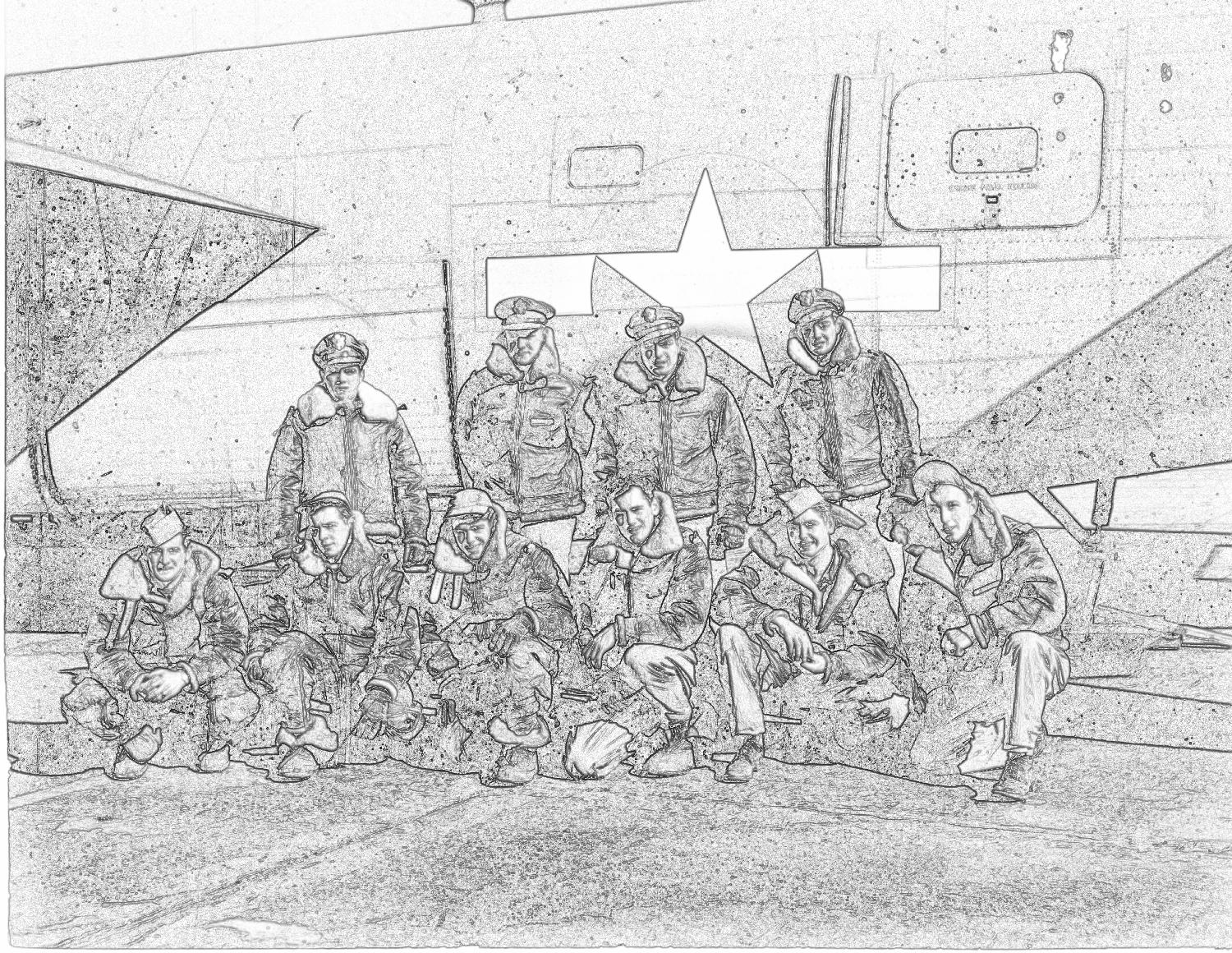

Crew at Horsham

F/O Murray Loy – P, F/O Harold “Bud“ Walker – P, Lt. Ted Joiner – CP, Lt Gordon Wyman – B, Ly Casimer Wysocki – N, Lt Howard Bradley – B

Standing: George Bayuzieck – E, Asa Compton – G, Thomas Rankin – RO

Kneeling: Lewis Wallace – AG, Robert Herman – G, Robert Johnson – G

(Photos: Anne Zimmer & Bayard Wilson)

June 24, 1944

The Airmen – Chapter 34 Control

There were rough days ahead in the program of preparation for the amphibious assault on Fortress Europe. A new Eighth Air Force report averred that the daylight strategic bombing program was under threat: too many enemy fighters. Something had to be done, because the Germans were raising their fighter production and transferring more fighters to the western front.

The year 1944 opened with a reorganization of the United States Army Air Force operations in the European Theater. Lieutenant General Carl Spaatz was appointed commander of the United States Strategic Air Forces in Europe, Major General James Doolittle replaced General Ira Eaker as commander of the Eighth Air Force, and Eaker took Doolittle’s old command in the Mediterranean. The emphasis on daylight strategic bombing was stepped up.

The warning about German Fighters was underscored on January 11, when 570 B-17s and B-24s bombed industrial targets at Halberstadt and in the Brunswick area. Five hundred German Fighters came up to meet them, and the sky was one great melee. In the end 60 U.S. bombers were lost.

The loss ratio was simply too high, so until other arrangements could be made, the bombing of Germany was to be stopped for a while. But by the end of January the insistence on the bombing program from on high made it necessary to resume heavy raids and heavy losses.

January 29, 1944 was the day that Captain Robert Sellers (above, left) became a senior flying control officer of the 458th Bomb Group. The mission of January 29 [the 458th were en route to the ETO at this time, and did not participate in this mission] was another rough one. For the first time, more than 760 heavy bombers struck at heavy industry in the Frankfurt-am-Main. Nearly fifty of the bombers got lost and bombed Ludwigshafen. Over the main target the fighter opposition was fierce, and twenty-nine planes were lost. One of the big problems for cripples coming home was an inability to find the base, partly due to the weather.

Captain Sellers was well aware of this problem and felt a heavy responsibility to do what he could to solve it. “We felt that if pilots were to place their aircraft in our hands in time of emergency we should do things that told them, ‘We really know what you are facing, so have confidence in our instructions.'”

Just after the Second Bombardment Division was put on a maximum effort basis, the 458th was ordered to fly a mission to interdict German fighters and fighter production. They were to hit airfields in western Germany and aircraft factories in the Brunswick area.

Looking at the operations board [on June 24], Captain Sellers noted that Lieutenant [F/O] Bud Walker’s airplane was scratched from the mission and learned that one crewman was sick that day. So Captain Sellers offered to take his place, a suggestion that was welcomed by the lieutenant and the others because they were sweating out the last few of their combat missions [Walker and crew were actually only about halfway finished at this point]. Sellers did not have to fly any missions. He was a control officer, not an air crew member. But he wanted to go.

Captain Sellers was assigned to man the nose gun turret and to help the navigator from that forward position. As they flew into Germany, Sellers noted that the group leader was taking them on a course that would put them directly over a heavy flak area. He passed the word to Lieutenant Walker, and Walker radioed the group leader.

“I’ll check it out”, said the group leader. But if he did check it out, he did not get accurate information, because they kept straight on course for trouble.

As Sellers recalls, “we were flying at 22,000 feet, and the sky was so clear that we could look straight down at the ground.” Of course it was just as clear for the Germans down below.

We soon learned that the Germans had been using their time to track the first flight on its course, checking height and speed and fine-tuning their sites. They let them go by. Then, as we came along, they let loose.

One anti-aircraft battery fired four bursts. The first went off in front of me; the second literally tore the No. 3 engine off the wing; the third tore off the bomb bay doors and our bombs went tumbling out; and the fourth burst went off just outside the left waist gunner’s window.

The B-24 slid to the left and raced toward the ground as the two pilots struggled to straighten it out. Lieutenant Walker sent an alert through the intercom, “Prepare to bail out.” In a few seconds the aircraft dropped 8000 feet, spinning out of control. Fortunately the dive had taken them out of the range of the flak batteries and there was no more firing. Still, the aircraft was badly hit and shuddered so violently that Captain Sellers figured it would come apart.

“I came out of the nose turret and saw holes all around in the fuselage, but I was not even scratched. Sergeant ‘Bugs’ Bayuzik came out of the upper turret and joined me in making a quick damage assessment. Through the hatch to the bomb bay we could see the damage, or some of it. The doors to the bomb bay were completely gone, and we had a hole 10 by 15 feet in the airframe. Control cables were hanging loose and something – either gasoline or hydraulic fluid – was spraying all over.”

The rear hatch of the bomb bay was open, but they could not see anyone in the rear of the aircraft. Captain Sellers went to the cockpit and told the pilots not to use the intercom because of the danger. They talked for a minute about bailing out, but first Lieutenant Walker wanted to know what had happened aft. What about the belly turret gunner, the rear turret gunner, and the two waist gunners?

Captain Sellers signaled the flight engineer to follow him and moved to the open hatch, intending to cross the catwalk of the bomb bay. He picked up a portable oxygen bottle and disconnected it from the ship’s system. He put his legs through the hatch onto the walkway; his parachute was blocking his way, so he took it off.

“The wind was howling all around me and pulling at me as I stood up; and as I turned to move across the catwalk, I noticed one of the waist gunners lying on the floor of the plane. He raised his arm. So at least someone was alive back there. Then the wind caught me. My foot slipped in the liquid spraying out (which was hydraulic fluid) and I went down, straddling the catwalk and hanging on for dear life.

“Bugs grabbed me by the arm and pulled me back. I looked down. It was a long way to the ground. My God, I thought, and I’m out here without my chute!”

Sergeant Bayuzik helped him back into the forward compartment. Then they looked at the oxygen bottle. The gauge read zero.

Captain Sellers then went back to the cockpit and told them that at least one man was alive, though wounded. So Lieutenant Walker decided to stick with the aircraft, and the copilot, Sellers, and the flight engineer did too. They would try to get the B-24 home.

The flight engineer went back up into the top turret to keep a watch for enemy fighters. Lieutenant Walker did a little tentative experimenting and found that by reducing speed he could reduce the vibration. But with the No. 3 engine out they had no brakes or flaps, and the copilot did not think they would be able to crank the landing gear down by hand.

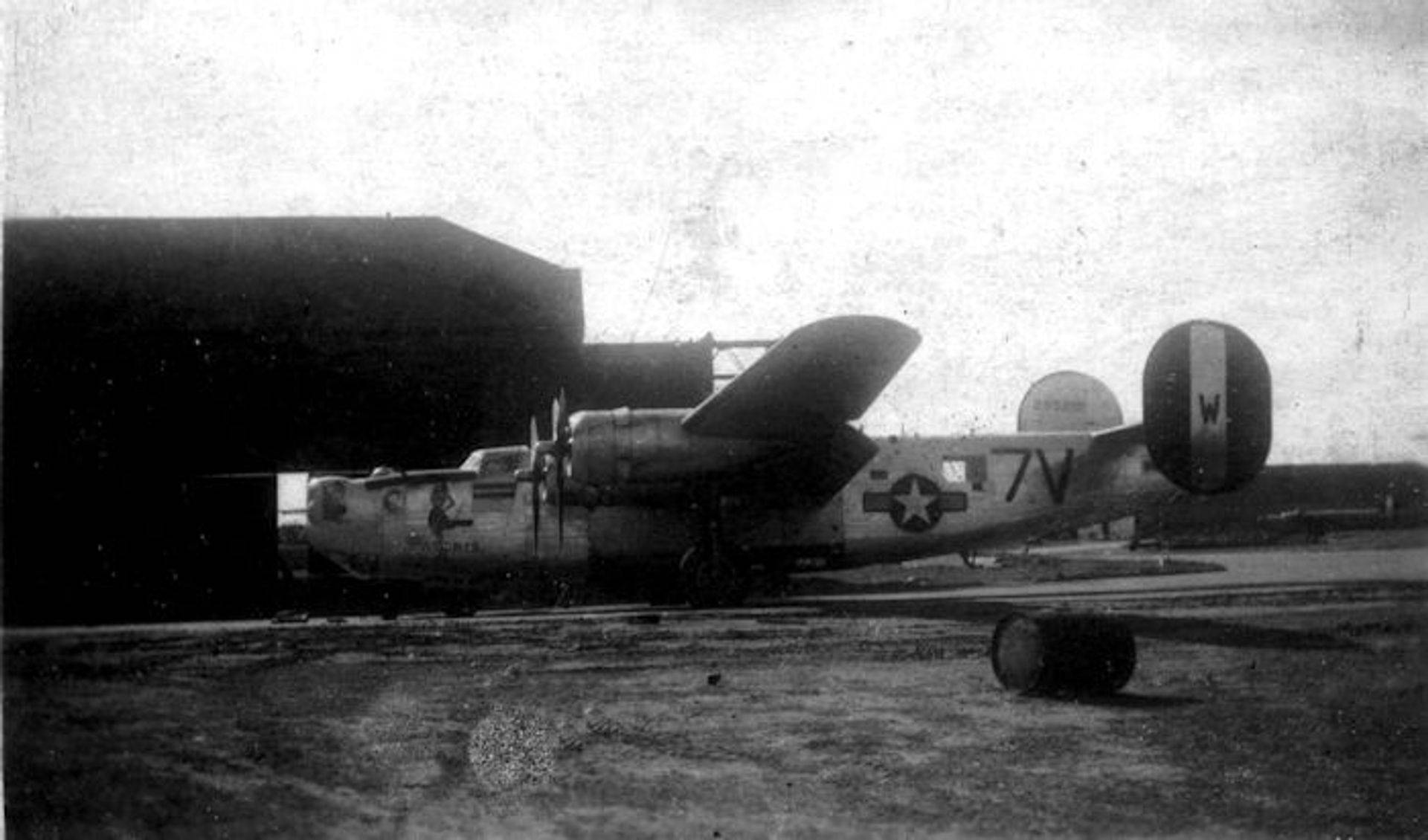

B-24H-25-FO 42-95219 7V W Patchie near one of he hangars at Horsham

Full of trepidation, they limped along back toward the English Channel. Lieutenant Ted Joiner, the navigator, studied his maps and came up with a shorter route to Manston, the closest field, where they could shoot for an emergency landing.

Captain Sellers stood in back of the pilots, leaning on the seat backs, and watched the English coast come up. Soon he spotted Manston. He told Lieutenant Walker to head for the field.

“‘Don’t call them’, I said. ‘We might catch fire. We’ll shoot flares. That will tell them we have been hit.’ We all watched the fuel gauges on the working engines. The indicators were very near the empty mark.

‘Lieutenant Walker and the copilot were having a real struggle to keep the aircraft on an even keel. We lost altitude constantly, because every time Walker tried to gun the engines, the vibration started again, and the plane shuddered violently.”

Ahead of them was the emergency runway: 3000 feet of grass undershoot area, 9000 feet of pavement, and then another 3000 feet of grass overshoot area.

“We headed straight in. I saw several fighters preparing to land, but they were not a problem. They would be using a different runway.”

Then came the green light from the tower, giving them clearance to go straight in.

Lieutenant Walker headed in, but he was too low. It looked like they would land on the undershoot grass, but he managed to get the plane up a little. They hit the macadam at 150 mph and bounced. Captain Sellers could sense that either they had blown the tires on impact or the tires had been shot up. The B-24 skidded down the runway, and the nose wheel collapsed. The plane ground looped off to one side of the runway, and then came to a stop.

Up front they got out of the aircraft in a hurry, worried about fire. The crash crew was there, firefighters and all the rest, and they got the wounded out of the back of the plane. Nobody was dead.

As the ambulances took away the wounded, Captain Sellers (left) looked over the aircraft. It was lying on its side, one engine gone, the wing peeled back, and full of holes (later the mechanics counted 700). Flying control’s weapons carrier picked them up and took them to operations, where the flight surgeon presented them with their combat ration: a shot of whiskey each. They needed it.

Captain Sellers then called their home base and was told that they had already been reported as missing in action.

“Hey,” he said, “please send the chaplain to our quarters to tell them that we are okay. I don’t want to lose my Short Coat.” So the chaplain was dispatched and got to the BOQ in time to save their personal belongings from the “He won’t need these anymore” syndrome. Then the crew of Walker’s bomber minus the wounded gunners, made arrangements for transportation back to the base. And other day’s work was done.

——————————————————-

From 752nd Engineering: As of July 1 there were only 10 planes left in the Squadron with camouflage paint. The planes of the 752nd are soundly cared for and can “take it”. Proof of this is B-24 number 42-95219 piloted by Flight Officer Harold A. Walker, which crash landed at MANSTON, England, on June 24 after receiving 350 flak holes over DIEPPE.

(Photos and book excerpt: Robert Sellers, Jr.)

Air Medal (Oak Leaf Cluster)

2BD GO206

August 25, 1944

HAROLD A. WALKER, T-123231, Flight Officer, Army Air Forces, United States Army. For meritorious achievement, while serving as Pilot of a B-24 aircraft on a bombing mission over enemy occupied territory, 24 June 1944. Over the target, flak hits wounded two members of Flight Officer Walker’s crew and severely damaged the control mechanism and hydraulic lines of his aircraft. Flight Officer Walker skillfully maintained control of his crippled aircraft to reach an emergency field where he landed without further damage or injury to the crew. The courage and superior flying ability displayed by Flight Officer Walker on this occasion reflect the highest credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of the United States. Entered military service from Michigan.