458th Bombardment Group (H)

WACs at Horsham

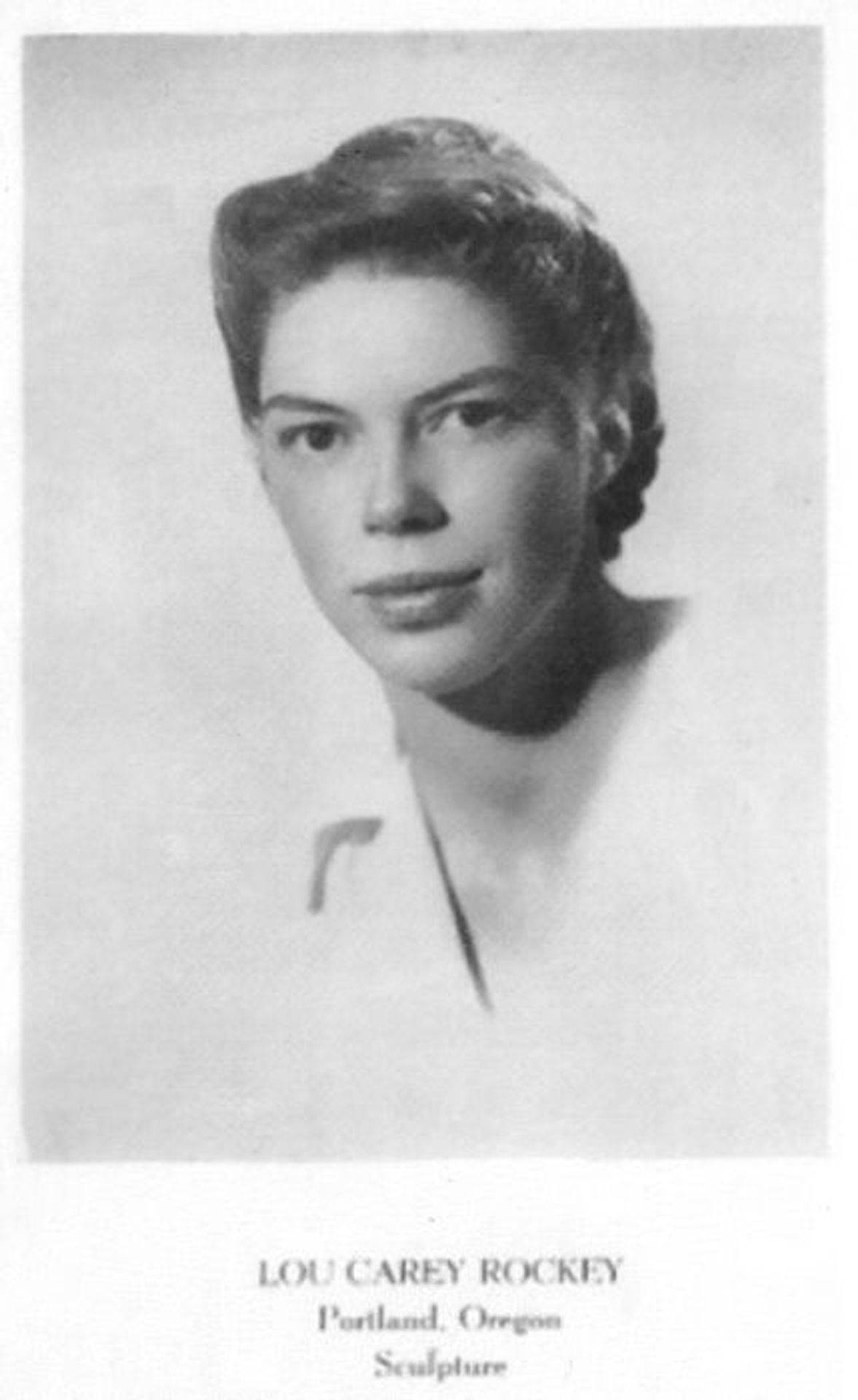

1LT LOUISE CAREY ROCKEY EVANS[1]

WAAC/WAC, 1942-1946, Serial No. L903406, U.S.A. and England

Louise Carey Rockey was born in Portland, Oregon, on 10 November 1921. Her family had lived in Portland for three generations. Her maternal grandfather, Judge Charles H. Carey, was a noted lawyer, author and historian; her paternal grandfather, Dr. Alpha Eugene Rockey, an early Portland physician.

Carey was graduated from Scripps College in Claremont, California, in June 1942, majoring in sculpture. During spring vacation in 1942 she returned to Portland for a short time. She visited her family’s beach house in Gearhart. There she saw barbed wire strung all along the beach as a defense against Japanese submarines and troops who might come ashore from ships off the coast.

She wanted to join the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) but was unable to do so because she was not yet 21. After graduation from Scripps, to mark time until her November birthday, she attended the San Francisco School of Fine Arts. She signed up in San Francisco for the WAAC on 2 December 1942, receiving a call-up in January 1943. Carey was quite put out by the delay. She had urged one of her best friends, Carol Mount,[2] to join; Carol, a year older than Carey, enlisted in September 1942.

Carey’s reasons for joining were twofold. Her grandfather Dr. A. E. Rockey; her father Dr. Eugene Rockey; and her uncle Dr. Paul Rockey all served in the medical corps in World War I (the brothers were stationed overseas). After the Pearl Harbor attack, her father volunteered to serve in the 46th General Hospital, a medical unit reactivated in 1942 at the University of Oregon Medical School.[3] To his dismay, Dr. Rockey was rejected because of a thereto undiscovered heart condition.[4]

Carey’s second reason was simply that she wanted to be in on the action.

Her eight-week basic training was at Fort Des Moines, Iowa. After basic, because she was a college graduate, she was sent to Officers’ Candidate School (OCS), also at Fort Des Moines. She describes the unpleasant climate in the area as, depending on the season, a bone-chilling -35°; unbearably hot and humid; or knee-deep in gummy mud.

The eight weeks of OCS consisted of an assortment of training programs such as military customs and courtesy; marching; military sanitation; first aid; map reading; company administration; supply; interior guard; and mess management (in other words, similar to basic training). Upon graduation as a Second Lieutenant, Carey was assigned to the Third Regiment at Fort Des Moines as a company officer. Her job was to assist fellow officers in the basic training of new recruits.

Both white and African-American women were trained at Fort Des Moines. During Carey’s time there, she saw no black enlisted recruits mix with white recruits, for training or otherwise.[5] And of course service clubs, theaters, beauty shops and the like were segregated as to race for both recruits and officer candidates. It was a slightly different story with female officers.

Coming from the northwest, Carey had had little interaction with black Americans. Her sole experience was knowing the mayor of Gearhart (where the Rockeys’ beach house was) who was black. At Fort Des Moines, she was assigned as one of her roommates an African-American officer,[6] for whom she had great respect. When it came to choosing who would take which bunk, Carey, being younger, chose the upper bunk, thoughtfully leaving the lower bunk to her older bunkmate.

One incident brought home to Carey how African-Americans were treated in this country. She and her roommate took a train to Chicago; they sat with one another and had a fine trip. When they arrived, Carey suggested they find a restaurant and eat dinner. Her fellow officer refused, saying blacks could not eat with whites, and that was that.

Carey recalled how frustrated she was with the recruits she drilled on the parade ground. All of them, she said, had two left feet. She would point out the perfect marching of the black platoons and ask her recruits why they couldn’t march like that.

Eleanor Roosevelt visited Fort Des Moines in February 1943 while Carey was there.[7] It was the first time Carey saw the enormous garrison flag displayed. Everyone was to be lined up in ranks on the parade ground; the uniform of the day was heavy overcoats and buckled-up galoshes on account of the cold weather. As it happened (Iowa weather being capricious), the day was quite warm. One by one, the troops began fainting from overheating. In order to keep Mrs. Roosevelt from seeing the WAACs’ distress, Carey quietly escorted each in turn to the back ranks, thereby missing the First Lady’s talk entirely.

Carey’s next duty station, in late spring of 1943, was the Army Administration School located at Eastern Kentucky State Teachers’ College in Richmond, Kentucky (about 30 miles southeast of Lexington). Her duties included inspecting quarters;[8] arranging for entertainment and meeting the USO performers when they arrived;[9] standing rotational Military Police (MP) duty in Lexington; and serving as mess officer.

The mess was run by civilian contractors, so Carey had few duties as the mess officer. One situation she handled occurred when the butcher was jailed for some infraction, likely being drunk. A hanging half-carcass of beef needed cutting up for the next meal. Carey knew how,[10] so in 90-degree heat and 90% humidity, she butchered the carcass.

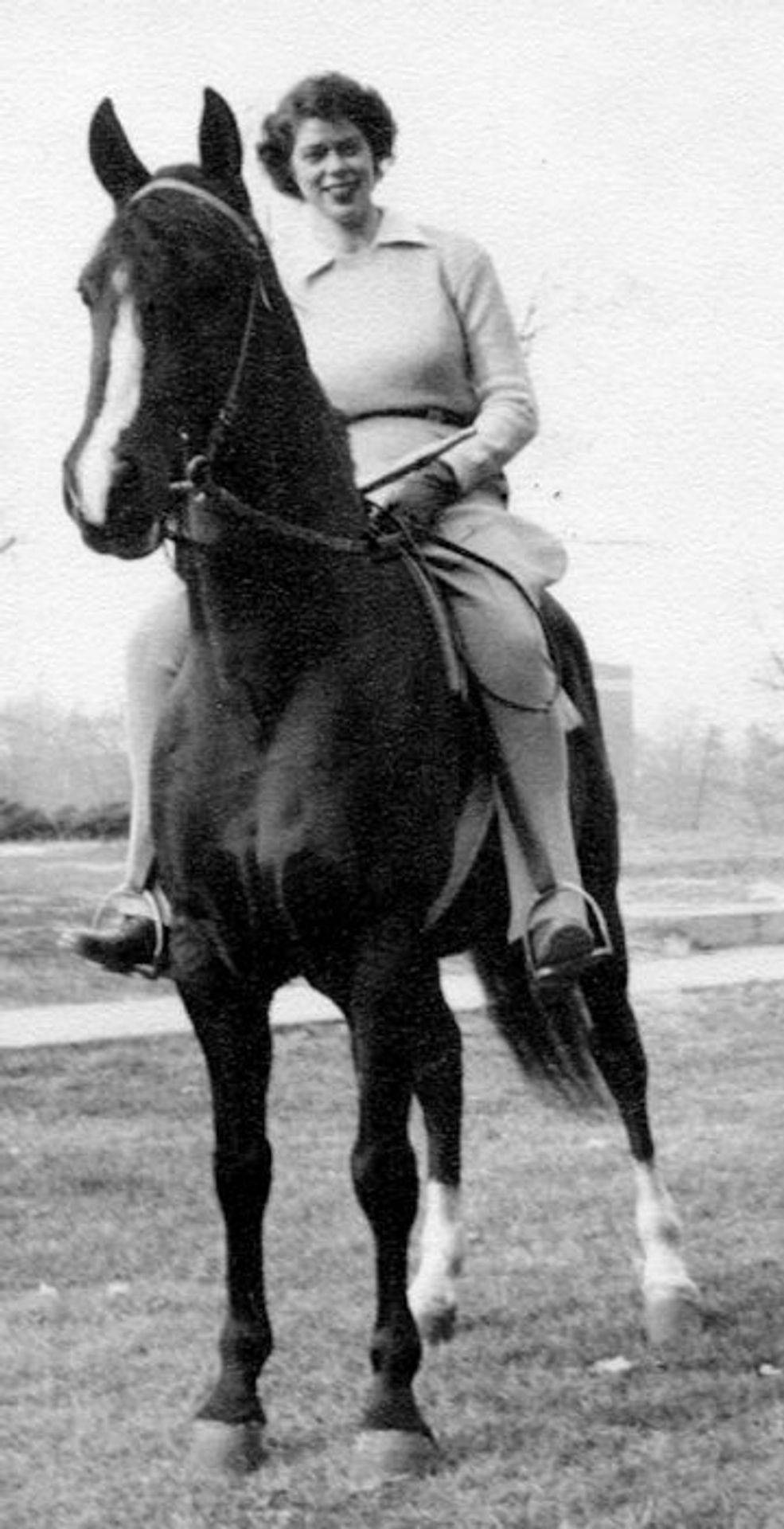

Kentucky was the right place for a horse lover to be stationed. One day in her off hours, Carey was given the chance to ride any horse in a stable. She chose a handsome Tennessee Walker stallion (his stablemates were all “plugs”, in her opinion). She put him in a snaffle-bitted bridle, cinched up an English saddle, and led him into a field. No one in the amazed, gathering crowd had warned her that the stallion was considered a bad-tempered outlaw and that he’d bucked off even seasoned cowboys. While the horse did buck a little and reared a time or two, otherwise he behaved well, and she rode him almost daily afterward. Carey chalks up his good behavior to her being “young and dumb”. Other factors were doubtless her gentle touch and the fact that he was cooped up in his small stall unless he toured the countryside with her on his back.

It was while stationed in eastern Kentucky that she saw the other side of life. When patrolling Lexington as an MP, she saw the red light district and the city jail’s drunk tank (no WAACs were ever found in either one). Poverty was rampant. Children had very few clothes and went barefoot; many men were crippled from coal mine injuries and unable to work; bad booze brewed by bootleggers (Madison County was a dry county at that time) caused deaths and illness in the civilian population.

Unchallenged by the somewhat mundane tasks given WACs,[11] Carey put in to go overseas. In the winter of 1944 in New York City[12] she boarded Queen Mary for Great Britain. Nearly 15,000 troops were aboard. The stabilizers did not function, hence the crossing was extremely rough. All water aboard that was not used for cooking or drinking was sea water. Fourteen officers were assigned to a stateroom, where they slept in wooden bunks stacked three high. The WACs ate their meals on a roof that covered the swimming pool. The cooks were English, and the food was spooned in one great heap into each person’s mess kit.

Although Queen Mary was faster than German U-boats, she was chased by one, so the ship sailed north of the Arctic Circle, safely landing in Gourock, Scotland (northwest of Glasgow). Carey took a train to London, where she was lodged in an impressive home at 10 Charles Street in Mayfair, the most posh London neighborhood, between Hyde Park and Buckingham Palace.[13] The home was owned by a wealthy American married to an Englishman; the owner gave over its use to female American officers during the war. Carey would stay in this house whenever she spent the night in London.

Two weeks later she was assigned to Headquarters, Ninth Air Force Bomber Command in Earls Colne, Essex (about 60 miles NE of London).[14] The Command flew primarily B-26 Marauders (medium bombers) and A-23 light bombers. She had very little seniority and was an administrative officer.

Marks Hall, HQ of the Ninth Air Force Bomber Command. Few original buildings remain; the large mansion, first built in 1163, was demolished in 1950 due to disrepair. Much renovation was done in the 1970s and ‘80s, and it is now an arboretum. The nearby Earls Colne Airfield is a golf course and private airstrip; the outline of the WWII runways and perimeter are visible from the air.

She was billeted in a “Nissen hut”, similar to a Quonset hut, and her office was in a nearby Nissen hut. Outside of them was a large trench. The troops were to leap out the doors and windows if bombs were heard overhead. Bombs fell frequently because these living quarters were close to Earls Cone Airfield, and airfields were favorite targets of the German Luftwaffe. She bicycled to the mess hall, a half-mile away on the other side of the airfield, at Marks Hall – a Jacobean, and later Elizabethan, country house – where the Command’s HQ was located.

Beginning in May 1944, curious events began to occur. The Command’s planes had black and white stripes painted around their wings and fuselages.[15] During that month her job was to type up countless equipment lists. All personnel were restricted to quarters until further notice. Everyone walked on eggs. On June 5, an officer said he could drink no liquor because of “big training tonight.” Carey and others had suspected for several weeks that an invasion of France was in the offing; the next morning, 6 June 1944, it was clear that D-Day had arrived when the bombers took off at 5:00 a.m.

Shortly after D-Day, the Nazis began launching their new V-1 rockets at London and environs. Carey particularly remembers their distinct putt-putt-putt or buzzing sound, and when the engine cut out, you hoped it was well past you, because in a few seconds it would hit the ground with a tremendously destructive explosion.

Following D-Day, her company was sent to France, but she was left behind. Cary was reassigned to RAF Horsham St. Faith near Norwich[16] on England’s east coast (about 120 miles northeast of London), the home of B-24 heavy bombers.

96CBW: 1Lt Louis Carey Rockey and 1Lt Ruth R. Johnson

There, she was attached to the 96th Combat Bombardment Wing. As operations officers, Carey and three other WACs performed administrative work, such as keeping track of where the aircraft were. The other WACs were 1LT Ruth Rose Johnson (1916-1992); 2LT Dorothea Joanne Affronte (1917-1983); and 2LT Virginia N. “Ginny” Justy.[17] Carey stayed in touch with Ruth Johnson and Joanne Affronte for a time after the war. Ruth was a teacher from Oregon; Joanne was from New Jersey. Ginny, the oldest of the four, had divorced a band leader because she was tired of the constant travel and hotel living. She then joined the Army, while her ex-husband moved to Hollywood where he became a screen writer.

The four WACs were billeted in the back part of a larger building, the front of which housed some function such as offices or the base exchange. Their cooking facility was a hotplate on which they brewed hot chocolate. They had three rooms: one contained two sets of bunk beds; another was a little bathroom; and the third was a small parlor. The parlor housed a tiny, inefficient stove that ran on coke. The WACs’ coke allotment was minuscule. They found that they could increase their allotment, and thereby the temperature, by liberating coke from the establishment in the front of the building.

During her service in England, Carey flew on as many different military aircraft as there were pilots willing to take her. She hitched rides on Piper Cubs; B-17s; B-24s; and B-26s. As the war was winding down, she rode in a C-47 (the military version of the Douglas DC-3) that was headed to Kassel, in central Germany, with Red Cross personnel aboard to retrieve about 30 wounded American soldiers. No one talked about the injuries or how the men were injured; all of them were, however, ambulatory. Carey chatted with them and they exchanged small souvenirs.

In the fall of 1944, flying was reduced enough that four WACs were not needed in the operations office. Carey was transferred in October to RAF Burtonwood in Warrington, halfway between Manchester and Liverpool on the west coast, and about 170 air miles northwest of Norwich.

At Burtonwood, she was promoted to First Lieutenant and appointed mess officer (one of her jobs was to censor all letters written by her staff). She overheard an enlisted serviceman remark to another, “Well, we got us a new mess officer and it’s a damn lady.” More than 3,500 meals were prepared and served every 24 hours.

She had an excellent mess sergeant working for her. She let MSGT Bernard Robbins do his job and never had to get involved in the day-to-day details. She respected him enough that she stayed in touch with him and his wife until he died when in his 80s.

Carey was invited to parties at the Bachelor Officers’ Quarters, but the men were all much older and she didn’t drink. An event showing her quick thinking and ability occurred one night when she got a call that an enlisted man was in the mess, threatening the staff with a knife. The staff dove for hiding places (mainly in the cupboards). Carey showed up to find the very drunk, would-be combatant marching around the mess hall, wielding a large knife. She fell in step with him and marched until he tired and gave her the knife.

Carey and Sam Evans (left) had met before Sam’s near-death landing on 18 August, but they didn’t know each other well. Afterward, while she was still stationed at Horsham, they began seeing each other. Upon her transfer to Burtonwood, they visited as often as they could. Carey would take the train to London where she would meet Sam, or from London on to Horsham (Norwich) where they would meet. She would do the reverse to return to Burtonwood (Warrington). Sam and a few of his crew members once tried to fly her to Burtonwood in a B-24. The weather was so bad over the Burtonwood airfield that after circling it for about 20 minutes, he flew back to Horsham, meaning that Carey had to take trains, via London, back to her base.

Sam returned to the states in February or March of 1945, having completed his 30 missions. This did not end his military obligation, however. He was sent to Hamilton Field north of San Francisco where he was re-trained to fly Douglas C-54 Skymasters.[20] Sam flew supplies to points in the Pacific (and Japan, following the Japanese surrender). After his discharge in the fall of 1945, he returned to Texas where he resumed his studies and completed his second year of college at the University of Texas. Carey says Sam wanted to be sure he could support his bride when she finally returned from England and was discharged.

Carey herself did not have an easy time getting out of the Army. She happened to be in London on V-J Day (Victory in Japan, 14 August 1945) – the “Yanks” were ecstatic (the English were enthusiastic). By this time, her father, whom she calls something of a hypochondriac, desperately wanted her home because he was convinced he would soon die from heart problems. Carey learned that a medical discharge would get her home more quickly than anything else. Declaring simply that she wanted to go home, she was consigned to the psychiatric ward of a hospital in Malvern near the border of Wales. A nurse announced almost immediately that Carey did not belong there. Carey then said she had a bad knee (which she did), and was at last sent to the states in a hospital ship (a converted freighter). It was a rough crossing owing to a hurricane that the ship encountered.[21]

After arriving in New York City, Carey was sent to a military hospital in the San Francisco area. There, her bad knee was declared a minor problem. While in the hospital, she met and spoke with other patients who had arrived from the Pacific front – many of whom had been Japanese POWs. Thus she learned what had happened in the war in the Pacific. She was at last discharged and was home in Portland for Christmas, 1945, although the official discharge paperwork didn’t come through until January 1946.

Notes

1 By C. Clark Leone, © 2015.

2 Carolyn Mount Clark was interviewed by Alicia Hamel, Executive Director of the Historical Outreach Foundation Museum, in March 2014. Carol and Carey are lifelong friends. They grew up together; their parents were very close; and both are 1942 Scripps College graduates (Carol is a year older than Carey – Carey skipped fifth grade).

3 Carol Clark’s father, (LTC) Dr. Frank R. Mount, was the Executive Officer of the 46th General, serving under (COL) Dr. J. Guy Strohm. (Jun. 2015).

5 Carey’s observation comports with various articles about segregation between races for enlisted recruits, e.g., Military Women’s Memorial (Jul. 2015).

6 Carey’s situation belies the then usual living arrangements for black and white WAAC officer candidates. Ibid. Black officer candidates did, however, attend classes and mess with white officer candidates, Women’s Army Corps (Jul. 2015).

7 Eleanor Roosevelt Papers (Jul. 2015).

8 Her most vivid recollection during those inspections is of the huge, lively cockroaches that dropped from the ceilings and crunched beneath her feet.

9 Carey is a long-time animal lover and had a horse at an early age (she continues to ride a horse to this day). She was no city kid. During one of the USO shows, a performer parodied walking through a cow pasture. Only Carey and one other officer understood the mime and were the only ones who laughed uproariously.

10 OCS had provided a 20-minute or so program on cuts of meat; moreover, Carey had cut up wild game her father hunted.

11 The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was converted to the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) on July 1, 1943.

12 After Richmond, she was, for very short times, in Louisville, where she was assigned no duties, and Georgia, where troops were assembled to be sent by troop train to New York City and then on to England by boat. Just before leaving New York, Carey mailed Carol Mount her heavy overcoat, figuring she wouldn’t need it in England. Carol was most grateful (and still owns the overcoat).

13 One night, a local cat gave birth to kittens on her bed.

14 Although Carey has periodically kept a diary throughout her life, she did not keep one while overseas. She and her colleagues were ordered not to because it might fall into German hands. For once, and unfortunately for posterity, she took a warning seriously.

17 458BG Personnel List (Aug. 2015); each is listed alphabetically by last name under “Ground men”.

18 An account of CPT Evans’ military service accompanies this document.

19 The Command Pilot is a passenger aboard the aircraft that leads the squadron (which consists of several B-24s). He commands the squadron, while the pilot of the aircraft that the Command Pilot is aboard is in charge of that particular aircraft.

20 These were the aircraft that Americans flew to get food, water and other supplies into West Berlin during the 13-month long Berlin Airlift in 1948-1949. The Soviets, controlling East Germany in the middle of which West Berlin sat, blocked the Allies’ railway, road and canal access, so the only way to support the population of 2,500,000 was by air.

21 Carey was not seasick on this voyage. She was seasick once on Queen Mary, though, because Air Corps officers fed her what turned out to be speed pills either to help her stay awake or to help avoid seasickness – in any event, the pills made her seasick for several days.