Swingle Crew – Assigned 752nd Squadron – April 20, 1945

Transferred from 453BG

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Crew Pos / Job Title | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1Lt | Raymond R Swingle | 0833278 | Pilot | 20-Apr-45 | FEH | Assigned from 453rd BG |

| 2Lt | Theodore W Clark | 0830823 | Co-pilot | 20-Apr-45 | FEH | Assigned from 453rd BG |

| 2Lt | John T Harrington, Jr | 07072724 | Navigator | 20-Apr-45 | FEH | Assigned from 453rd BG |

| T/Sgt | Ralph S Gordy | 18186688 | Flight Engineer | 20-Apr-45 | FEH | Assigned from 453rd BG |

| T/Sgt | John M McCarl | 13188051 | Radio Operator | 20-Apr-45 | FEH | Assigned from 453rd BG |

| S/Sgt | Arthur J Simpson | 36866701 | Armorer-Gunner | 20-Apr-45 | FEH | Assigned from 453rd BG |

| S/Sgt | Melvin Weaver | 18124999 | Armorer-Gunner | 20-Apr-45 | FEH | Assigned from 453rd BG |

| S/Sgt | William F Hicks | 18248529 | 2/Flight Engineer | 20-Apr-45 | FEH | Assigned from 453rd BG |

| S/Sgt | Chester Fong | 39135989 | Armorer-Gunner | 20-Apr-45 | FEH | Assigned from 453rd BG |

Assigned to the 752nd Squadron at the end of the air war in Europe, there is very little information on the Swingle crew in the 458th records. Having arrived at Horsham only five days prior to the Eighth Air Force’s cessation of bombing operations, they were able to fly the last mission of the war on April 25th. This crew had flown more than 20 missions with the 453BG prior to their transfer to the 458th.

This crew was assigned to ferry B-24H-15-CF 41-29567 7V G My Bunnie back to the States in June 1945.

Mission with 458BG

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25-Apr-45 | BAD REICHENHALL | 230 | 1 | 42-51270 | A | 7V | 44 | MY BUNNIE II | LAST 8AF MISSION |

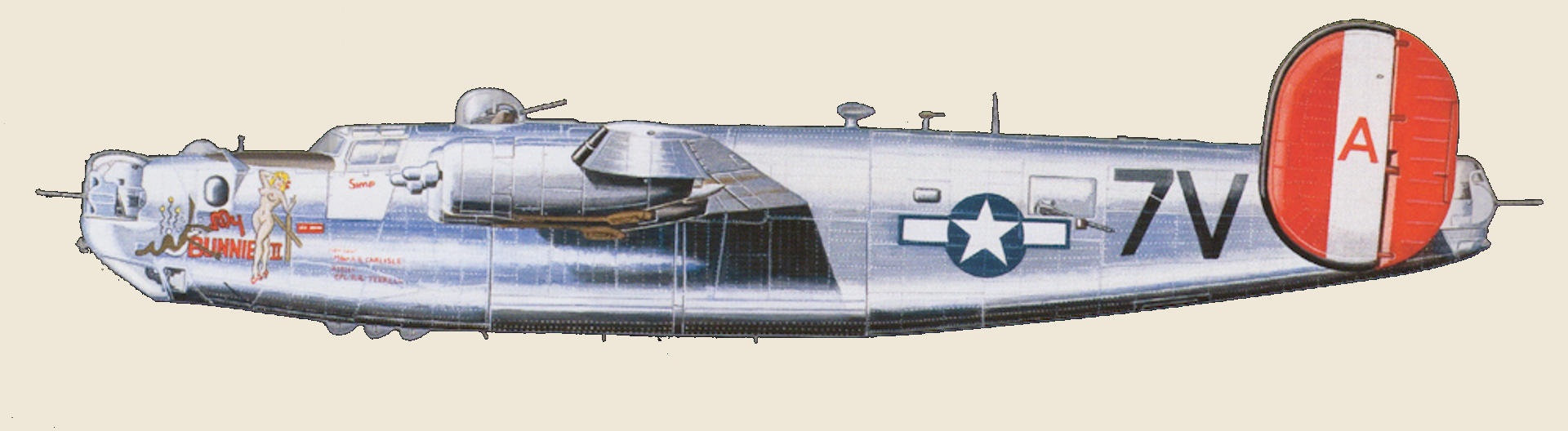

B-24J-1-DT 42-51270 7V A My BUNNIE II

June 1945

Dad’s Wartime Service: “Plowing the Rutabagas”

Some of this is true…

John T Harrington, 2LT U.S. Army Air Corps, SN O7072724

I want to tell the story of Dad’s Wartime Service, a series of vignettes and impressions that I grew up hearing about. Some veterans of WW2 seldom talked about their experiences. For Dad they were constantly in his mind and he talked about them often. Unlike some vets he was very outspoken about his wartime service with the 8th Air Force, part of the US Army Air Corps (USAAC).

The Internet has much information available to augment the stories and give them relevance. There are B-24 blogs and websites with scanned documents posted. Many armchair historians have tracked down, scanned, and posted every scrap of paper and photo they came across for the greater good. Because of this I have found mission reports, crew lists, and photos to use as references.

Dad flew 23 combat missions, and was part of the last 8th AF heavy bombing mission of the ETO, to Bad Reichenhall. He was haunted by his experiences, and suffered occasional nightmares the rest of his life.

Enlisted Man

Dad got drafted into the U.S. Army as an enlisted man. He could have received a deferment since he worked as a tool & die maker, a critical wartime skill. One of his projects was to develop an underwater cable cutter to cut through mine cables and underwater entanglements. It was a hand-held device that would hook around a cable and used a blank shotgun shell to propel a hardened steel blade against the cable, cutting it through. Navy frogmen would use it to clear floating mines off beaches that were being invaded. It could be used with one hand, and was designed to be one-time use and disposable: hook the device around a cable, trigger the internal shotgun shell to cut the cable, and drop the device. A key feature was that it was sealed, so no bubbles were given off that could give away the frogman’s position.

Dad’s basic training class was selected en masse for the Air Corps. The class in front and behind him ended up in the Normandy invasion on D-Day.

Dad ended up after basic training in Charleston, South Carolina. When his unit arrived during the heat of the day they went into the barracks and were astounded that there were several blankets at the foot of each bed. “Typical stupid Army,” they muttered, “giving us blankets in hot weather.” Later that night every blanket was in use as the night-time chill descended.

He stood guard duty and had to enforce blackout regulations. Lights from the shore could silhouette transport ships against the shore and make them easy targets for German U-boats. His orders were to give a warning and then shoot out any light if it wasn’t shielded. He had several altercations with people who would not shield their lights.

Dad liked to target shoot and made friends with the armorers. One of them had built up a personal M1 carbine that he had reworked to “match grade” perfection. Dad shot it and said “you couldn’t miss with it.”

As part of enlisting the men received batteries of tests to determine their suitable assignment, and after basic training Dad was sent to aircraft mechanic’s school. He scored high in mechanical aptitude, since he worked as a tool & die machinist after high school. He received his A&P (Aircraft & Powerplant) rating, as well as a promotion to Corporal. Dad was very proud of the promotion, at least as much as his experiences with cadets to become an officer. His A&P rating came in handy later on when he was on a flight crew. Afterwards he applied for navigator school and was accepted. It was a nine week program, and also he became a “cadet” for officer training school. So he was commissioned as a second lieutenant, from corporal.

Training

Part of Army life was taking lots of tests. He scored highly and was able to go to OTS (Officer’s Training School) as a cadet, to become an officer. He volunteered to be in the Army Air Corps. In terms of cadets, they were the lowest of the low. Everything was done like boot camp on afterburner, with yelling and an accelerated pace. if you couldn’t keep up, you were washed out. There were always minor, made-up infractions that had to be worked off “walking a post,” with a seat-pack parachute strapped on so that with every step, you got thumped in the legs. Dad soon became accustomed to walking posts.

Dad ended up in Michigan to go through OTS. Ironically, Dad scored excellent in math and for a time, taught math at Michigan State University to others in the Army. One of his greatest shocks was the whole class jumping to attention as he entered the room to teach the day’s lesson, even if they outranked him.

Navigator training lasted about 9 weeks. Part of becoming a Navigator was to also be a pilot. Dad learned to fly at Romulus Field in Michigan. He trained in a Porterfield aircraft, similar to a Piper Cub: tandem two-seater, single engine, high wing monoplane. Once when he was up with an instructor, they were over the field and his instructor saw another rival instructor in the pattern about to land. He told Dad to “spin it!” so they could land ahead of the rival. Dad protested they were right over the field but the instructor said “That’s an order! Spin it!” Dad put the plane into a spin and recovered in time to land ahead of the other instructor. The two instructors jumped out of their planes and traded harsh words on the tarmac about who was supposed to land first. Dad and the other student pilot, being lowly cadets, were left out of it and could only stand there and watch the excitement.

Later he took multiengine training and transitioned to the B-24. A little known fact is that the B-24 could be flown like a fighter when stripped down, no guns, armor, or heavy fuel load. On training flights, the instructor would flip the plane around and Dad had to recover to level flight, even with an engine feathered. It taught him great respect for the bomber’s capabilities.

Golfing

Dad learned how to play golf as an officer. They had recreational opportunities to try out, including expert instruction from golf pros hired by the Army. Because of that, Dad had a lifetime hobby with golfing….he even joined the golf club when he worked at Sikorsky Aircraft later in life. The Army took pains to have its officers become gentlemen to foster cultural refinement like learning to play golf.

Building a Plane

After Dad got commissioned and got his navigator’s wings, he was assigned to an air base where there was a big lag in his orders coming through. He palled around with a bunch of fellow officers when the light bulb went on. It was a training base for Douglas A-24’s, a hot two-engine ship. Turned out there was a large junkyard of airplanes that had suffered training mishaps. Dad had his A&P and was a scrounger, so they set about making a good plane from all the junked ones. Fuselage, wings, tail, engines…they borrowed all the tools, built up an A-24 from parts, and got it flying. They were able to get fuel and supplies since it was just another U.S. Army Air Corps plane on base, who would suspect anything? One of the guys was from Texas, so on one trip they flew to his home town and ate authentic Mexican food for lunch. They would then fly around on other trips, Dad doing the navigating. Until one day, they were getting ready to fly and the base commander got in their plane and sat in the pilot’s seat. “Let’s go flying,” he said. The others were all dumbfounded and stricken with fear of a massive court-martial. Somehow the word had got out they had their own private plane. With all the guys aboard the base commander took off, made some maneuvers, entered the pattern, and landed. Then he gathered the guys together and said “This is the best A-24 I’ve ever flown. Everything on it is perfect. But it doesn’t have a tail number, so officially it doesn’t exist. And it is hereby grounded!” They had to take it back to the junkyard, and no other action was ever taken. That was the informal culture that existed in wartime.

Going Overseas

Dad shipped out on the luxury cruise liner Aquitania that had been converted to a troop transport. His berth was far below in the bowels of the ship, beneath the water line. His job was to be the last man out of his section in case the ship was torpedoed and sinking. He recalled being on deck to get some fresh air and noticed the sun traversing back and forth from one side of the ship to the other as it took a zigzag course. No one was allowed on deck at night in case someone showed a light, such as if they lit a cigarette, and the glow would reveal the ship’s position to a marauding U-boat. The ship traveled alone and relied on its speed for protection. They arrived New Year’s Eve, 1944, with the next day being January 1st, 1945.

Dad served in the European Theater of Operations (ETO) in the 8th Air Force, in a B-24 Liberator bomber. At that time there were two heavy four-engine bomber designs, the Boeing B-17 and the Consolidated B-24. The 8th was divided into Air Divsions operating similar types. The 1st and 3rd AD flew B-17s, the 2nd AD flew the B-24. So Dad was in the 2nd Air Division.

The Swingle Crew

Dad’s crew was a happy one that all crew members got along well, with one man out as I’ll explain. I was able to get a list of Dad’s crew with ranks and serial numbers as of 20 April 1945, from a personnel transfer ordering them from the 453rd to the 458th Bomb Group, 752nd Bomb Squadron:

Raymond R. Swingle 1LT O632278 Pilot/Aircraft Commander

Theodore W. Clark 2LT O830823 Copilot

John T. Harrington 2LT O7072724 Navigator

Ralph S. Gardy (748) TSGT 18186688 Aerial Engineer/Gunner

John M. McCarl (757) TSGT 13188051 Radio Operator/Mech/Gunner

Arthur W. Simpson (612) SSGT 36866701 Armorer/Gunner

Melvin Weaver (612) SSGT 18124999 Armorer/Gunner

William F. Hicks (748) SSGT 18248529 Aerial Engineer/Gunner

Chester Fong (612) SSGT 39135989 Armorer/Gunner

*** NEWS FLASH *** Chester (Chet) Fong, the last surviving crewman from the Swingle crew recently passed away on Feb 3rd, 2017. I am in contact with his relatives, trading photos and memories. Chet saved a bomb tag from every mission flown, as a souvenir. He was the tail gunner.

Dad always referred himself as belonging to the 458th BG, but he started out and had most of his time with the 453rd. The main reason for transfers: late in the war (1945) it was realized that the ETO would soon run out of strategic and tactical targets as the Nazis were being pushed back into Germany and the occupied countries were liberated. It was known that soon, the war would be over in Europe. Personnel with fewer than 15 missions were reassigned to the Pacific Theater of Operations, or PTO, which was still active against the Japanese Empire. Those with 15 or more missions were all reassigned to a different bomb group within the ETO. So the Swingle crew transitioned to the 458th.

The officers have an “O” at the beginning of their serial number, the enlisted men have just a plain number. Of special note is that Dad’s crew had a Chinese-American, Chet Fong, as the tail gunner. All enlisted flight crew members were Sergeants, in this case either Tech Sergeant or Staff Sergeant. This, for recognition of their skill level as a flight crew member, and also better treatment if shot down and captured as a POW, among others. The number in parentheses is their military operational specialty, or MOS.

In a mechanized war such as WW2 the people involved identified themselves with their unit and hardware (tanks, ships, planes, etc). Dad’s crew was known as the “Swingle Crew” due to its Aircraft Commander, 1LT Raymond R. Swingle. It was realized that crew integrity was important to survive combat, so (as much as possible) crews were formed and stayed together throughout their tours but maybe had a different plane for each mission. And Dad identified himself with the B-24, thought it was the best plane ever. There was a friendly ongoing rivalry between the B-17 and B-24 about which was better. Each thought the other had an inferior plane, with the B-17 being referred to as the Flying Outhouse (or flying shithouse, depending on the audience whether it was the more polite version). The B-24 was called the Big-Assed Bird by the B-17 crews, due to its twin tail.

Dad was over 22 years old in 1945 and was called “Pops” since he was actually one of the older men in the unit. He also had the nickname “Red” due to his red hair. That was when he had hair before going mostly bald later in life.

The tail gunner had a critical job on the mission, to announce periodic “oxygen checks” to have every crew member report in. Anyone not reporting was checked on, since at 30,000 feet (the height of Mt. Everest) the air was too thin to breathe. Anyone passing out due an oxygen system malfunction or the hose freezing up could die from anoxia within a few minutes.

Their radio operator carried extra crystals (used to tune the radio set) and was able to receive stations from Switzerland and pipe music over the intercom to the crew.

Nine Men? Why Not Ten?

The crew list reveals nine men instead of the usual ten. The Bombardier is missing, for two reasons. First, at that time in the war each plane having an individual bombardier became superfluous. Each bomb squadron flew in formation, with all other planes dropping when the lead plane did, so only that plane (plus the alternate) really needed a bombardier. Meaning, the bombs of the squadron either all hit or all missed. When they missed the term used was “plowing the rutabagas” since any scrap of open land was planted with rutabagas, a root crop, to feed the German people.

The other reason was that Dad refused to fly with a bombardier, after an incident where the assigned bombardier went beserk on the way to the target. The nose of the B-24 has barely enough room for two men (Navigator and Bombardier) behind the nose gunner, especially when encumbered with flying suits, flak jacket, oxygen masks, Mae West inflatable life preserver, pistol, and helmet. The navigator had a tiny seat and desk to calculate their position, with the bombardier up front with the Norden bomb sight right below the nose gunner. One mission, Dad was at his desk doing a calculation when he heard over the intercom “I’m going to kill you.” He looked up and there was the bombardier pointing his .45 automatic pistol at Dad’s head, the muzzle inches away. Then he turned to the nose gunner and said “Then I’m going to kill YOU,” who was looking over his shoulder into the compartment in terror. The nose gunner had to climb in and out of the powered turret through two tiny saloon-type doors, very difficult to squeeze through, and thereby never would have been time to react. The bombardier then scooted through the tunnel up onto the flight deck, and pointed his gun at the pilot and copilot. Dad had followed behind and jumped him, wrestling him to the deck and taking away the .45. The other crew members tied him up with intercom wire and it was a long flight to the target and back home, with the man struggling to get loose and yelling the whole time. They radioed ahead what had happened. After landing they were directed to a remote area on base where MP’s took the bombardier away and they never saw him again. From then on Dad dropped the bombs. He taught himself how to use the Norden bombsight. Several times they were the lead ship so Dad toggled for the entire squadron. I have the bombardier’s name, but for privacy reasons will not reveal it. His episode could have been from anoxia-induced breakdown from oxygen starvation, and it was not uncommon for men to crack up from the strain of combat flying.

Two 45’s

That’s how Dad ended up with two .45 automatic pistols, He had his own, and the one he took off the bombardier. He wore them in twin shoulder holsters, one each on his right and left hand shoulder over his leather jacket.

Dad liked shooting the .45. He made friends with the group armorer and they’d go into one of the revetments and each shoot a case of 500 rounds each. Dad could shoot with either hand and got quite good at it. He also liked to shoot the tommy gun which also fired the same pistol round.

Since Dad was a scrounger he also tried to smuggle his .45’s back home. Returning GI’s were told their belongings would be thoroughly searched for contraband such as weapon bring-backs or government property. When they flew the plane back home Dad hid them under the Norden bombsight. Two screws held the Norden bombsight in place. There was a small tray under the sight that allowed the pistols to be nested unseen after the bombsight was re-installed. After they landed and got searched Dad was going to go back to the plane and remove the guns. As it turned out, after landing they were whisked away from the plane and were not searched at all. He could have kept them in his baggage. The plane went straight to the scrapyard. So some airman who removed the Norden bombsight got lucky.

Dad’s Planes

Dad flew missions in several different planes: in the 453rd BG: a B-24H-25-FO (Serial No. 42-95214, built by Ford at their Willow Run plant) named “Wandering Wanda” after a popular song of that era, and also the co-pilot’s wife was named Wanda (there was another B-24 in the PTO with the same name, in a different bomb group). The 453rd flew out of Old Buckenham air base. Another was a 458th BG B-24J-1-DT “My Bunnie II” (752nd Squadron “7V,” Serial No. 42-51270, built by Douglas Aircraft Company at their Tulsa plant). The “42” in the serial number means it was ordered in 1942. This was not the delivery date, which came later. Google the serial number, and it comes right up with some photos available to view. My Bunnie II featured a fully naked woman on the nose art. An order went out later, that all full frontal nudity nose art had to be painted over with at least a bikini. The high command did not want the enemy to think our boys were pornographic. The 458th flew out of Horsham St. Faiths air field, a former P-47 fighter base. The ferry flight home likely was flown in “My Bunnie” B-24H-15-CF, s/n 41-29567. That plane was transferred from the 34rd BG that was originally trained in B-24s but was reassigned to fly B-17s. Chet’s relatives have identified a third plane, “Becoming Back” B-24J-65-CF (SN: 44-10575, built by Consolidated Fort Worth), and sent a photo of dad’s crew (with Dad), plane “H6” in the squadron.

Bad Language

One mission the plan was to have several different bomb groups each approach the target from a different direction and altitude so as to confuse the defenses. Split-second timing would enable them to bomb the target in successive waves. Naturally, as it happened the groups all arrived over the target at the same time and bombed through each other. It was a miracle no plane got hit by a falling bomb or had a mid-air collision. While this was going on the planes were radioing each other on the command channel with lots of profanity and worse, and in violation of security measures named names over the airwaves. Their commanding officer was especially subject to abuse. Unbeknownst to them, all the talk was being recorded back in England on a wire recorder. When they returned the groups involved were assembled to hear what they had said played back to them, and got a severe tongue-lashing.

Cheating at Cards

A card-trick magician (I believe it was John Scarne, a famous magician) was recruited by the Army to travel around to various bases and warn servicemen about getting into rigged card games. He would gather a group together, shuffle a deck of cards and deal out poker hands. He’d always deal himself four aces or someone else four kings or four queens at will. Then he’d shuffle the deck and repeat the whole thing all over again. Or, he could deal himself or anyone else blackjack every time. His motto was, if I can do it, someone else can and you’d never know it. So don’t get into card games—you’ll get cheated. Dad met him while in the service.

Dad played blackjack a few times and had some winning hands, but he wasn’t into gambling.

Iron Pants

Dad had a cute little dog, a scotty named “Iron Pants” since it left puddles in the barracks. Later on he changed the dog’s name to “Hot Tip” for the latest hot tip about when the war would end. Dad inherited the dog from a crewman who rotated home, and handed it off to someone else when he rotated out.

Spare Compass

Dad always flew with a spare compass since guys would sneak into the plane when it was parked, and drink the alcohol out of the liquid-filled aircraft compass. So emptied, it would then freeze up at altitude, rendering it useless. Dad carried a folding British Army marching compass with radium-painted needle and compass card to use in the plane. It was very well made, and is still in the family today.

Gee

Dad was trained on the British navigational aid “Gee” which was a primitive LORAN system, high-tech for its day. It was a system where synchronized radio signals were sent from ground-based stations located at a known distance apart. The airplane had two radio sets tuned to each frequency. When the two directional signals matched cross-hatched lines plotted on a chart your location was known, within a few miles depending on the distance from the transmitters.

Birthday in London

The British people had a tremendous affinity for U.S. servicemen in WW2. I have met many who, even today, show exceptional gratitude. Dad’s birthday was May 17th, and he was allowed leave to go to London. While there he had a nice meal and when the waiter asked if there was anything else, Dad stated it was his birthday and asked for some strawberry shortcake. He had always had strawberry shortcake on his birthday, and realized due to wartime rationing it was probably an impossible request. The waiter brought out a huge piece of shortcake with a heaping mound of the most succulent and perfectly ripe strawberries. How they could get them during wartime was a miracle. Dad left a tip that was more than the entire meal. So there’s an unknown waiter that made a lonely GI’s birthday far from home a memorable one.

Out and About

Another issue with the grateful British people was that they frequently invited servicemen into their homes for a dinner or drink. The men received lectures on being a good guest, especially at meal times. Due to wartime rationing a family might have a piece of meat for Sunday dinner for the entire family, that was far smaller than a single serving in the mess hall (and with “seconds” available). So if you were offered a platter to size it up and take only a small portion divided equally among the diners. Also, if offered a friendly drink to do so in moderation so as not to use up the host’s supply of spirits, that were extremely difficult for civilians to replace.

Dad visited Wales when he first arrived on the Aquitania, thought the countryside was absolutely beautiful.

They were warned about the Piccadilly Commandos, as well as not becoming romantically involved with British women in time of war. Yet, I’ve met several wartime couples that had the British wife emigrate to the United States as a war bride, and stood the test of time.

Dad had several buddies he would go into town with. One of them carried a British Army revolver he had got in trade, with the barrel cut down with a hacksaw so it could be concealed in his pocket. Why the guy felt he needed a gun was a mystery…maybe to fight off Piccadilly Commandos. One day they went to the range to test fire it. The guy took careful aim at a 55-gallon drum ten feet away, and fired all six shots. One bullet out of the six hit the barrel off to the side, and made a small dent. Not much of a defense gun.

Flying Around

Dad liked flying in the war, he said except for getting shot at it was very nice. They flew near Berchtesgaden (Hitler’s mountain retreat) but were strictly forbidden to bomb it on pain of serious court-martial. They also flew near the Swiss border on occasion. The Swiss were expert gunners and would put up a line of flak bursts as a warning. If you entered their airspace, they would shoot you down. To surrender the signal was to drop your wheels and they would let you land and be interned. The Swiss ended up with quite a few airmen and aircraft by the time the war ended. A few intentionally surrendered, since if an aircraft had low fuel or battle damage and couldn’t make it back, the Swiss were far better captors than the Germans. Dad loved flying near the alps, said they were quite beautiful. He also flew over Peenemunde, the German rocket science base headed by Werner von Braun. They were forbidden to bomb that as well. The RAF were assigned to hit Peenemunde.

Flying into Germany you always bucked a headwind “You’d crawl into Germany,” was one of his sayings. Dad would take a sighting with his octant every so often to calculate the position, and had a small periscope pointed down to observe features on the ground for navigational landmarks. On one mission he sat and watched a farmhouse far below that didn’t appear to budge for a good fifteen minutes, due to the headwind. They were red-lined at 170 knots Indicated Air Speed (IAS) but usually flew far slower, even though a stripped B-24 could approach 300 IAS at full power. With a stiff headwind, it was impossible to make any ground speed. They had strict rules about maintaining formation. A lone plane or scattered formation was easy prey for the lurking fighters.

The USAAC had very strict rules about where to bomb. If the target or secondary were obscured, then the orders were to drop the bombs in the English Channel rather than drop them at random over Germany or bring them back. No bomber was allowed back to base with spare or hung bombs, too great a risk of crashing and blowing the place up.

Since Dad was a trained mechanic he sometimes helped the ground crew with repairs and maintenance, and made friends with the crew chief.

There were strict orders among the gunners not to secure the guns until after landing. The Germans had a practice of sneaking a Ju-88 in the landing pattern and shooting down a few bombers before high-tailing it back to base. Some gunners would start cleaning the guns after crossing the English Channel since late in the war the Luftwaffe was not as active, and it left the plane defenseless.

The rule among escorting fighters was, if you had to join up with a bomber group fly a parallel course and tip the plane up so the gunners could see the wing shape and recognize you were a friendly. Any plane aiming at the group would be fired upon, since there was no time to tell friend from foe. Dad said the enemy fighters came at you so fast there were mere split seconds to react.

There was a general who spent the war as a POW by violating that rule. He was flying in a British DeHavilland Mosquito as a roving observation plane above the bomber stream. When he put his nose to the bomb group to join up with them, the B-24 gunners promptly shot him down. He and his co-pilot parachuted to safety but were taken prisoner. After the war he tried to find out who shot him down to reprimand the gunners, but was told he was in the wrong, not the gunners.

The Trip Home: One Chance Might Be All You Get

Dad and his crew flew back to the States by way of the Azores, a group of Portugese islands off the coast of Africa. They received briefings on how to make the trip. The engine carburetors had been re-jetted for lean operation, and they were told to fly at low power settings for maximum efficiency that made them gasp…the plane would fall out of the sky at that speed! But the Air Transport Command lecturer told them this is how we do it on long flights to get distance and conserve gas, so can you. Also, in the Azores, the runway was at the top of a cliff overlooking the sea. You had to fly straight at the cliff edge and an updraft would lift the plane up and gently position it for landing. If you tried to make a normal landing and drop down on the runway, the updraft would make you balloon up high and land long on the runway, leading to an overshoot. For the trip they carried extra GI’s on board who had priority to get home.

As it turned out, they took off and immediately found themselves in the soup flying on instruments. They couldn’t find a homing beacon on the radio. They were flying blind, relying on dead reckoning to estimate their course and position. Dad was sitting there as the hours went by, making calculations on their estimated route that he had no idea if their calculated position was any good. Suddenly the plane broke out into a clear area. Dad jumped up and got one good sun sight reading on his octant before it socked in again. From that one reading, he made his position calculation and ordered a course change. After dead reckoning a calculated course, speed, and time, several hours later he told the pilot to drop down. At that moment the clouds parted and the airfield was right in front of them.

That lesson made him later on take any opportunity offered, since you might not get another. He attempted to pass that attitude on to us kids.

There is a photo of a B-24 “My Bunnie” B-24H-15-CF, s/n 41-29567 (with the similar nose art as the “My Bunnie II”) for the ferry flight. It belonged to his squadron, the 752nd (7V designation). I believe this was the plane he flew home in, since it has a crew photo of the plane, crew, and passengers.

To the Unknown Airman

One of the first things Dad got exposed to was the horrors of war. Right after he got in theater a plane came back that had been hit by flak, with a dead gunner aboard that had been pulverized and unidentifiable as a man. Since he was one of the most junior officers Dad had the grim job of washing the airman out of the turret with a fire hose and collecting the remains in buckets. That really haunted him the rest of his life, and reminds us all of sacrifice: The Unknown Airman. His name is certainly recorded in the official records, but to me he stands for the many lost in aerial combat. The 8th AF lost more men KIA in WW2 than the Marines and Navy combined, not to mention wounded or captured.

Operation Varsity

Dad had an absolutely horrific mission with the 453rd dropping supplies to paratroopers during Operation Varsity, the last airborne drop of the war. The strategy was to make a bridgehead across the Rhine and end the war faster (unlike the earlier failed Market-Garden drop described in A Bridge Too Far), with the British and American paratroops dropped at Wesel. Dad’s plane was loaded with supply canisters that each had a distinctive color parachute for what was inside: red for ammunition, white for medical supplies, green for food, blue for water, etc. The paratroopers could tell what was inside by a glance at the chute color what was inside and then know where to get the supplies they needed without opening up every canister to look inside. During the mission they actually flew below treetop level…pull up to get over a fence, dodging between trees, looking up at rooftops. And for good reason: flak was intense and accurate. They made the drop but were horrified at the carnage. Dad said he could look straight across and see the paratroopers’ faces as they were hanging dead from trees and telephone poles mere feet away. Also, he could look down on many crashed and burning transports (C-46s and C-47s) and crashed gliders with all aboard killed—hundreds upon hundreds dead. When they got back the crew chief called “Red, look at this.” Dad’s nickname was Red since he had red hair (before he went bald, that is). The wing of their plane (where the gas tanks are located) had taken numerous 20mm cannon fire hits, but without effect. The self-sealing feature in the tanks had done its job. Come to find out the slave labor that made ammo for the Nazis had their own little game of sabotage by leaving out the explosives in the shells. One explosive shell could have ignited the fuel and blown the wing off. At that low altitude none of the crew would have made it out.

Since Dad was an aircraft mechanic first, he helped out working on planes when he wasn’t slated for a mission. The crew chiefs liked him for that, he didn’t pull rank like he was too good to swing a wrench. After the Wesel mission, Dad helped work on the plane to get it fixed.

Chaplain

Dad’s group had a Jewish rabbi as the chaplain, a very capable man and sought out by many of all denominations for words of comfort. He rated the rabbi better than the Catholic priest that came around—and Dad was Roman Catholic. The air base also had a chaplain that would stand at the side of the runway to greet the returning planes. He had a large glass tumbler and several bottles of whiskey with him. When the crews left the plane they could each drink as much whiskey as they wanted, before heading off (staggering off, mostly) to debriefing. The benefit was, the guys were very talkative in interrogation with a few drinks. Unfortunately the WCTU (Women’s Christian Temperance Union) found out and there was a big scurry to stop the practice, since “they’re turning our boys into drunks.”

There was heavy drinking in the officer’s club, sometimes the guys were so hung over from the night before a mission they had to be helped into their planes. But breathing oxygen as soon as they got into the plane revived them instantly. The rule was to use oxygen at altitudes over 10,000 feet in daytime but many crews used it from the ground up (which flight regulations called for during night flying) for maximum alertness.

Judas Goat Missions: The Assembly Ship

Dad flew many of the “Judas Goat” missions, which didn’t count for combat missions. Each bomb group had a war-weary aircraft no longer suitable for combat that was stripped down and painted in a distinctive wild, bright color scheme to be used as an assembly ship to form up the bomb group into a coherent, self-defending assembly before heading out on the mission. Then the Judas Goat would peel away and return to base. The name comes from sheep slaughtering. A trained goat, called the Judas Goat, was used to walk into the slaughterhouse to lead sheep and cattle inside. Animals would not go into the slaughterhouse on their own, but would readily follow the goat to their doom.

Stripped down, a B-24 could be flown like a fighter…no armor, guns, bombsight, bombs, etc. and with minimum fuel really lightened the load. There was a friendly rivalry between the British Avro Lancaster bomber crews and the American crews. The British usually bombed at night but could sometimes be seen flying in daylight over England. The “Lanc” had higher performance than the American bombers. It could fly faster and carry a heavier bomb load than even a B-24. So one time, returning from a Judas Goat mission, they spotted a Lancaster flying alone. They swooped down next to the Lanc and feathered the props on the two engines closest to the British plane while gesturing to the RAF crew to go faster. Then, as the British crew gunned their engines to pull ahead, the Judas Goat climbed up and above them on the remaining two unfeathered engines to tease them.

Flak

Flak is an abbreviation of the German word “Fliegerabwehrkanone” which in a literal translation means “flyer defense cannon.” At that point in the war the Luftwaffe was being shot out of the sky (with the exception of the Me-262), but flak was increasing in intensity. You need two years to train a pilot, two weeks to train a flak gunner. All the crews were afraid of flak, since the “fighters came at you so fast there was no time to react.” But the flak was aimed from the ground and got walked in to your position and altitude. The crew had a gallows humor associated with it. If the flak bursts were hopelessly far off, it was “Adolf’s shooting at us again.” As the rounds came closer, Adolf was replaced by a buck private. As the bursts came closer yet, the rank of the gunner increased through the enlisted ranks such as Oberfeldwebel (Sergeant), to officers such as Leutnant (Lieutenant), Hauptmann (Captain), Oberst (Colonel). If the bursts were right in among the group with deadly accuracy, it was Herman Goering himself aiming the guns. The 88mm guns were feared, but then the Wehrmacht came out with a 105mm flak gun that was even more deadly.

Twice Lucky

Dad got a near miss by flak twice, among many other times the plane was hit. Once he was seated at his desk and a flak shell burst outside the plane. The shrapnel tore through the nose, destroyed his desk and charts, ripped off his glove and left him with a tiny scratch on a finger, “not worth a Purple Heart” was his saying. Another time he stood up to take a navigational sighting with his octant, standing on two little foot tabs (one on each side of the nose) to reach the astrodome. A shell struck the nose wheel and exploded, taking the entire nose gear and lower front of the plane away in one bang, along with his desk and charts. Dad said he looked down and there was nothing below him except Germany, standing on the two little foot tabs. On that mission they had to land at a specially prepared emergency runway away from the main airfield, made from plowed earth to slow the plane down if it had to belly in. Since they had no nose gear they landed there. They landed on the main gear, holding the nose up as long as possible before settling down.

He was not wearing a parachute, since in the cramped space available a chute was too cumbersome. Some crewmen wore a harness and clipped the chute on before jumping…if there was time. In the B-24, if badly hit there was almost no chance for the crew members in the nose (Navigator, Bombardier, and Nose Gunner) to get out in time. It was even hard for the pilot and copilot to get out. The bombardier, had there been one in the nose, would have fallen to his death.

Let’s Get the Hell Out Of Here

The expression they used after Bombs Away was “Let’s get the Hell out of here” before making the big turn and heading for home. It was a dire necessity to always keep the formation intact, since the fighters were waiting to pounce on a straggler or disorganized formation.

Attacked by Me-262’s

The first operational jet fighter of the war was the Messerschmidt Me-262. It outclassed anything the Allies had, but made its appearance too late in the war to make much of a difference. By then the Nazi regime was certainly going to be defeated, and didn’t have the fuel or trained pilots to put up many planes. The Me-262 had axial-flow jet engines, very advanced for its day, and packed 20mm, 30mm, and even a 50mm cannon depending on the armament. The tactic was to get a group of Me-262’s or other fighters and attack head on into a formation, each jet plane picking out a bomber to fire upon. If the bombers weren’t immediately shot down (and many were, by using this tactic), it would disrupt the formation into individual planes which were much easier to pick off. Once a group of Me-262’s formed up in front of Dad’s group and attacked head on. They made frantic calls over the fighter channel for help (their call sign was “Silver Dollar”) and from out of nowhere a squadron of P-51’s came roaring over the top, head on into the Me-262’s. Dad’s group flew through the resulting fur-ball of fighters and emerged unscathed.

Red Tails

Dad stated that at least once they were saved by the Red-Tails, what are now known as the Tuskegee Airmen. They were Negro Pilots (the name used at the time) who were trained as fighter pilots to see if black men could perform as well as whites. Of course, they performed brilliantly in combat. Dad gave them his highest esteem “Boy, could they ever FLY!” As a mark of distinction they painted the entire tail of their plane bright red. There are cases where enemy fighter pilots, upon seeing the red tail, would just bail out since they knew who they were up against. The Red-Tails were well-educated (all had college degrees) and well-spoken, but when over enemy territory would switch to heavily-accented “jive talk” since they knew the Germans were listening in on the radio chatter. There was a standing invitation to the Red Tails to land at their bomber base for a drink or dinner. The bomber guys would let them know what was on the menu over the radio. Sometimes, if the meal was particularly good that night, several of the fighters would have “engine trouble” and land at Dad’s base. They couldn’t buy a drink at the Officer’s Club. They were held in such high esteem the bomber guys bought them drinks and wouldn’t let them pay. After the war they unfortunately had to endure segregation until Civil Rights kicked in.

One issue about that, Dad made a point to use the “Colored” rest rooms when he was stationed in the South since he thought it was so ridiculous to have separate white and black accommodations. At times Southerners would come up to him, all flustered, “You used a COLORED rest room!” as if that was completely shocking. His answer was “Yes, it is colored. It is painted yellow inside.” That is, until someone reminded him that in the South, some will kill if you made fun of their customs.

After the war, as Dad was mustering out, he happened be in the mess hall and spotted one of the Red Tail pilots he knew and invited him to join them at his table. When someone at another table said out loud, “You guys are eating with a N—–r!” the entire table got up as one, and moved their plates and all to another table far away from the idiot. Then, they joined in friendly banter about missions they flew together and chit-chat as they finished their meal.

Observed the Me-163 Komet

The Messerschmitt Me-163 Komet was a rocket-powered fighter that was fueled by a hypergolic mixture of hydrogen peroxide and hydrazine hydrate, among other ingredients. It only had enough fuel for about 3 minutes duration. The plane would take off under rocket power, rise almost vertically to the 30,000-ft altitude of the bombers, and make one pass with its 30-mm cannons before the fuel ran out. Then it would glide to a landing. Dad saw them taking off with their long, vertical white plume of smoke left behind. The Me-163 was more dangerous to its pilot that anything else. One wrong move and the plane would explode. If the concentrated hydrogen peroxide fuel leaked into the cockpit it would actually dissolve the pilot’s body alive. The Me-163 had a (thankfully) unsuccessful career, with few kills.

Saw V-2 Rocket Launches

Dad witnessed a number of V-2 rocket launches. He said the smoke trail would go up thirty miles and arc over to the target (mostly London, and later Antwerp) until the fuel burned out, a mixture of liquid oxygen and alcohol. More Germans were killed by the V-2 than British, since they used slave labor in manufacturing and it took most of the German potato crop to make the alcohol fuel, leading to massive starvation. Not to mention, working the slave labor to death as a matter of routine.

Everybody a Pilot

Everyone on Dad’s crew knew how to fly, in case the officers got knocked out someone could fly the plane back to friendly territory. They had plenty of practice flying, since they were always getting an engine shot out and had to break in the new one (in a process called slow-timing) where they flew around and let the new engine run in with gradually increasing power. That meant everyone on the crew had a chance at the controls to learn how to fly and make practice landings.

Dad also fired the 50-caliber machine guns a few times in practice, thought it was a potent weapon.

End of the War Party

For every case of distilled spirits bought for the Officer’s Club, they took out one bottle to be saved for the End of the War Party. When the end finally came, there were wild parties at every airbase that lasted for days on end. Dad’s crew stayed together as they made the rounds, visiting other bases and fellow airmen in the group. One of the men in Dad’s group was so drunk he passed out (with a big smile on his face) and his buddies had to carry him around in a chair to various locations. As soon as he came to he’d guzzle from another bottle and pass out again. Few planes were flying until the festivities died down.

Dad’s Missions: 23 Round Trips

Dad’s comment was “I bombed Magdeburg visual three times” with a somber expression. It was a heavily defended, high-value target as important to the German war effort as Detroit was to ours. “Bombing visual” meant being able to see the target in the bombsight, instead of by radar through the overcast. That meant the target could see you and shoot back.

These were all in 1945:

16 Jan Magdeburg (Industrial Targets)

28 Jan Dortmund Oil refinery

3 Feb Magdeburg Marshalling yards

15 Feb Magdeburg (Industrial Targets)

19 Feb Jungenthal

21 Feb Nurnberg Marshalling yards

23 Feb Paderborn Bridge

24 Feb Lehrte Railroad marshalling yards

25 Feb Giebelstadt Giebelstadt Airfield

26 Feb Berlin Railroad yards

1 Mar Ingelstadt Marshalling yards

8 Mar Siegen Marshalling yards

9 Mar Munster Rail yards

12 Mar Wetzler Rail yards

15 Mar Gerdelegen Marshalling yards

17 Mar Munster Communications center

19 Mar Baumenheim Jet aircraft fields

24 Mar Wesel Air-drop supplies in Operation Varsity

4 Apr Wesendorf Airfield

8 Apr Furth Airfield

10 Apr Rechlin Airfield

11 Apr Auberg (Remburg?) Marshalling yards

25 Apr Bad Reichenhall 458th BG; last mission of the ETO

The mission on the 15th of February to Magdeburg coincided with the famous event of the bombing of Dresden by the RAF at night and the 1st AD flying B-17s by day, that created a massive firestorm and tens of thousands of casualties—very controversial to this day. My opinion: if it shorted the war by as little as a few minutes, it was worth it. Dad never thought twice about the missions he flew, to him they were out to destroy the Nazi regime and all it stood for.

Jimmy Stewart, Operations Officer

Of special note is that actor Jimmy Stewart was Operations Officer in the 453rd and flew many tough combat missions until being promoted up to Wing, yet still gave mission briefings. I attended a reunion of the 458th with Dad and the people there remembered Jimmy. They said he occasionally came to reunions and was one of the regular guys, no autographs or talk about Hollywood, just talk about the missions, friends, and families. He retired a Brigadier General in the USAF reserves. Also, he flew combat missions in the Korean War, and over Hanoi in the Vietnam War, unbeknownst to the public.

Letters From Home

Dad saved all the letters he received from home, from Mom (HS sweethearts that married on July 4th 1945 after he came home), and family. The ones he sent were also saved. He also received boxes of cookies from Mom. They were called “crazy cookies” since with wartime rationing she couldn’t get sugar and other ingredients to make them, yet they were good.

Growing Up in the Army

Dad graduated high school exactly 5 feet tall, his mother was 4 ft-11 inches and always said he would grow. Dad ended up 5 ft-9 inches when mustering out of the Army. He had to continually get new uniforms as he grew. Dad had huge hands and gorilla arms, which came in handy flying the B-24. It was heavy on the controls. Normally, the span for outstretched arms equals a person’s height. Dad’s span was about 6 feet. When shooting the 45 auto pistol, he said it felt like a cap gun in his hand.

Context

Adherents of air combat and strategic bombing point to a quick victory where the war could be won in an afternoon. In reality an air campaign is a lengthy, brutal war of attrition, with a high degree of random chance making you a survivor or a casualty. The 8th AF lost more killed and wounded than the Marine Corps and US Navy combined, and many more POWs.

The B-24 was the most-produced U.S. combat aircraft in WW2, yet only a few survive as of today (2017). Most of them were lost in combat or accidents, or scrapped after the war. It had the revolutionary thin and high-aspect-ratio “Davis Wing” and tricycle landing gear. Since the fuel lines went through the open bomb bay, any leaks would accumulate explosive vapors and at times planes were lost by just exploding in mid-air. The aircraft had greater range, speed, and payload than the B-17, but was not as stable or pilot-friendly. It flew like a truck, heavy on the controls, especially as they almost always flew way over the recommended gross weight limit. The common design platform of the B-17 was kept in production on later military and civilian aircraft—four-engine, low-wing, conventional tail. Dad got to fly a single-tail B-24 and said it handled beautifully, whether it really did or just had all the flight controls dialed in is unknown.

The choice of weapon for strategic bombing was the four-engine heavy bomber dropping 500-pound bombs. A usual full load for a B-24 or B-17 was ten or twelve 500-pounders, usually dropped all together out of the bomb bay. Even with the precision of the Norden bombsight, this load was selected to achieve a shotgun-like pattern on the ground and hope to hit something. The German war effort hit its peak in 1944 despite being pounded by air attack night and day, and raw materials running short. The only exception was, the fuel to run the war machine was critically lacking. Many times factories were back up and running within weeks of being bombed. The only sure way to destroy industrial capacity was to start a fire, with the heat that would warp the alignment of precision machine tools that made war materiel, rendering them useless and needing replacement. Otherwise, the the rubble would get cleared and any production machinery put back into use.

Dad bombed Magdeburg, which was their big industrial center like Detroit, Michigan except in Germany. Heavily industrialized, and heavily defended. Three times they made the trip, bombing “visual” which meant you could see them, and they could see you to shoot back.

A modern criticism of air power in the ETO was that there was no focused strategy. Targets were selected on a “flavor of the month” such as oil, transportation, electrical grid, aircraft production, and others. Very costly choices such as the Schweinfurt (ball bearing) and Regensburg missions, and the Ploesti mission, could not be followed up for complete destruction of the target due to extreme losses. There could not be the knockout blow so favored by adherents of air power, by conventional means. Combat losses and the lucky few who completed their 25 or 30 missions and rotated home meant a complete new air force with all new people and planes every six months. The Nazi war machine was very resilient at staying alive when being pounded by the U.S. by day, and the British by night—for years, not to mention the losses on the Russian front. Top Nazi armament output was achieved in 1944, but by then fuel and manpower shortages diminished their combat effectiveness. So the actual goal became by default the destruction of the German Luftwaffe. It was realized that no liberation of the continent would take place without secure air power. Missions and targets were selected to bait the Luftwaffe to come up and get shot down by gunners on the bombers and by escort fighters, choosing a target they HAD to protect such as aircraft factories. As a result, when Dad got in the war the Luftwaffe was a greatly reduced from its former potency by lack of skilled pilots. Flak (the famed 88’s, or 88mm gun) became the real danger. The Luftwaffe had the fighter planes, and good ones too, but not enough fuel or trained pilots to fly them later in the war.

Marshalling yards were another useful target—hitting the huge railyards where boxcars of war materiel were linked up to form a train. Not only did this destroy the war materiel, it destroyed boxcars and the rail complex itself. This greatly disrupted the mobility of the Nazi war machine. It also was a large target, easy to hit, with a smaller risk of hitting civilians.

Dad hated the Nazis with fervor for all the carnage they caused, starting the war and the Holocaust. Yet he did not hold a grudge against Germany (in fact, he selected precision German instruments to use in his tool & die work, and owned a German-made camera), only the political regime, Hitler and his cronies. Once the Holocaust was revealed, aircraft crews of all types were warned in strictest terms not to try and go after Hitler himself in revenge, such as attack Berchtesgaden. Later in life if the TV had a movie featuring Nazis, even if the the plot revealed them losing (like it usually did), he turned the TV off in disgust. He would watch Hogan’s Heroes, because the featured actor Robert Crane looked like an exact twin of his brother, our Uncle Jimmy.

The Hollywood War

Several attempts by Hollywood have presented an interpretation of WW2 air combat. Perhaps the best is “Twelve O’Clock High,” both the feature length movie made in 1949 and the 1960’s TV show. Dad hated watching it since it featured the B-17. But he watched it anyway, with a somber expression and adding several comments as the movie progressed. The movie presented a realistic portrayal of the 8th Air Force, with every scene in the movie relating to an actual event that happened.

Later, when the TV show came out by the same name, Dad would watch it and comment, even though (again) it featured B-17s. One episode featured the use of chaff to spoof enemy radar, which Dad said they used—tiny aluminum strips that when released would float down and jam radar signals. Another movie that brought up the grimness of aerial warfare was “The War Lover” again starring B-17s, along with Steve McQueen and Robert Wagner (also, in a rare moment of factual reality in film, actor Burt Kwouk starring as a Chinese-American navigator).

The recent movie “Unbroken” about Louis Zamperini featured B-24’s depicted with computer graphics (hard to get a real plane for filming, since there are only two B-24’s still flying today). Many television series in the 1960’s featured WW2, to come to grips with the cataclysmic events of WW2 on the small screen, dramas (such as “Combat!” and “The Gallant Men”) and comedies (“Hogan’s Heroes,” “McHale’s Navy”) alike.

The Tuskegee Airmen were featured in two movies: “The Tuskegee Airmen” and a later release, “Red Tails.”

More Context

Operations research and statistical analysis revealed survival to be heavily weighted by chance. If you lived or died, or were able to parachute to safety and become a POW was mostly random. With the heavy losses around him (both from combat and accidents) Dad had survivor’s guilt, and also survivor’s trauma that somehow he was selected to live. He had a large stack of business cards collected from fellow officers he’d served with. Many of them were marked with an “X” in the corner. When I asked about that, he said those were the ones that didn’t make it.

His telling comment about the whole thing was…with a haunted expression: “I bombed Magdeburg visual three times.”

Glenn Harrington

Last edit Nov 26, 2019