458th Bombardment Group (H)

The Southrepps Liberator

October 1944: Yankee Buzz Bomb sits in a barley field near the village of Southrepps

The village of Southrepps is just a little over five miles southeast of the coastal town of Cromer, and twenty-two miles north of Norwich. While this was a relatively quiet area, there was quite a lot of air activity and the village had witnessed a bit of excitement in the few years leading up to October 1944. On this date, the 458th bomb Group was assigned to bomb the Rothensee Oil Refinery near Magdeburg, Germany. The crew of 2Lt Albert H. Grice had drawn one of the 752 Bomb Squadron’s original aircraft, a B-24H named Yankee Buzz Bomb that sported a figure of the Disney character Goofy on the nose riding a very large bomb. This would be the aircraft’s 54th trip over enemy territory – for Grice and crew, their 5th.

Cloistered Cockpit

Recovering a battle-damaged Liberator from a British farm field was no easy task

The following article was written by the former historian for the 458th Bomb Group, George A. Reynolds. It appeared in the August 1982 edition of Air Classics magazine.

To most Americans, World War Two has become an era of the past – serving mostly as a milepost in time. But the survivors, those sixteen million citizens comprising our armed forces during that war, still consider it the epitome of the good old days or extinct tribulation. For it created, in each of them, enduring mementos of romance, suffering, blood and fire, goldbricking, destruction of specifically, “that day I almost bought the farm.” The latter typifies yesteryear’s airmen in the grandeur of an air force that was “the Mighty Eighth.”

Today, ex-Captain Tommy L. Land of Memphis, Tennessee, recalls that time vividly. “It was autumn 1944, in England and tools of war were changing. The familiar Olive Drab color of B-24’s I flew was giving way to a bare look of bright aluminum and especially garishly painted tail sections. This identified one airplane among many as belonging to a particular bombardment group.

“As vari-colored planes began arriving for major repairs at the 3rd Strategic Air Depot (SAD) field near Watton, those of us assigned this support duty paid little attention to the colors or their purpose. Nor did I realize how important some bright red ovals with a vertical white stripe would become to me in the near future.

“On 7 October, Liberator #41-29340 [Yankee Buzz Bomb] was in a flight of twenty-nine B-24’s over the North Sea enroute to bomb the Rothensee oil refinery at Magdeburg, Germany, when it lost two engines and turned back to England. Then its bombs were accidentally salvoed through the bomb bay doors, setting up tremendous drag. It reached the English coast however, and her pilot, Lt Albert H. Grice [pictured at right with his crew], ordered seven crewmen to bail out. He and co-pilot Neil A. J. Peters and the flight engineer remained aboard to save the aircraft.

[The co-pilot was actually 2Lt Clifford G Peters. Lt Neil AJ Peters was KIA in March 1944 when he and his crew ditched in the Channel. One man from the Grice crew, Sgt Edward J. Mire, was killed when his parachute failed to open.]

“They chose an emergency strip about four miles southeast of Cromer in a split second decision. It was a narrow, level barley field running north-south with a tall power line at the north [end], a deeply eroded ditch on the south [end] and trees at either side. But they landed safely.

“Later Captain A. R. Ayers of Bement, Illinois, inspected the damaged bomber for the 3rd SAD Mobile Repair Group and determined that it was repairable. Disassembly for removal was impractical because of huge labor and time factor involved. So, I went to the site to see if the airplane could be flown out.

“Normally a B-24 used about 4,000 feet of runway for takeoff. Here there was only 1,500 feet available – sod at that!! But heavy bombers were in critically short supply and our job was to repair cripples for return to combat service.

“A second look at the strip convinced me, with proper wind and humidity conditions, the fly-out could be made. Back at Watton, I told the maintenance chief, Major Lee Witzenburg of New York City, of my findings. He said, ‘Okay, Tom, you fly ‘er out and I’ll go along as flight engineer.’

“Next a crew from the 46th Mobile Repair Squadron, headed by Sergeant Harry Mundy of Rockridge, Ohio, was sent to make temporary repairs so the aircraft could be ferried to Watton for a major overhaul. To make the short field takeoff, removal of armament, radio gear and all other nonessential equipment was required. Only twenty minutes of fuel for the forty-mile flight was left aboard, and the crew was restricted to three men as further weight limitations.

“It rained, English style, until the fairly stable field became a quagmire of mud. Then, an engineering battalion assembled a 1,400 foot steel mesh runway. But it didn’t work. Under the plane’s weight, the panels sank right into the mud. Ah. Yankee ingenuity! After the matting was reassembled over a bed of straw, the problem was solved. Now we could only wait for a strong south wind and very heavy humidity for maximum lift.

“Sergeant Mundy’s crew worked diligently in getting the ship airworthy. The rest of us went about normal assignments, awaiting those ideal atmospheric conditions. We all knew the absolute necessity of having the ultimate in power on takeoff to get the bomber over that awesome ditch at the runway’s end.

“D-Day came on 17 November. Weather was poor over southern England, and combat aviation activity was completely grounded.

“In the early afternoon, Base Weather verified high humidity and predicted a stiff wind would hold until nightfall. But the ceiling was only 300 feet and visibility hovered around one mile. These would drop to zero-zero with darkness. My co-pilot, Captain Henry Miller of Mt. Kisco, New York, the major and I discussed the situation and the likelihood of a much longer delay, then decided to go ahead. We left for Cromer by jeep because there was no chance of flying into the field with our ‘baby’ occupying the only runway.

“When we arrived at the site, much later than planned, the mobile crew was exuberant. Excitement over the project was flowing in everyone. The air was literally oozing moisture as a light mist, so common to the United Kingdom, and that southern breeze was holding. But the delay in getting there, a final check of the plane and rechecking with Base Weather extended the takeoff time. We needed no surprises in weather or darkness at Watton. I phoned from a farmhouse, and the forecaster told me that present conditions were expected to hold another thirty minutes at least.

“As the engines coughed to life, I looked at Henry and Major Witzenburg. They were ready, the kite was ready. Those four turbo-charged Pratt & Whitney R-1830 engines were howling under full throttle. Baby jiggled like a hula dancer on the steel [matting], quaking against locked brakes. When I released her with propeller pitch full bore, and half flaps, she virtually leapt into a takeoff run.

“We roared down the strip and at the precise moment, Henry dropped full flaps to balloon the ship from the matting, at the 1,200-foot point, and over the gully.

“The ditch zipped under, we were airborne! Gear up, don’t sink! She didn’t. That gawky bird on the ground moments ago climbed like a homesick angel, steadfast and gracefully. Southward to Watton now.

“In our jubilation over a successful takeoff, we hardly noticed an airbase slip under the left wing a few minutes afterward. But our 300-foot altitude carried us within close range of the 466th Bombardment Group in Attlebridge.

“The ceiling began lowering and visibility dropped to almost nil in the misty sky. It was getting dark and, near Watton, the elements grew even worse. There were no navigation aids aboard, and we dropped lower to look for our field’s runways. But nothing looked familiar. I was lost and if we flew over the airdrome, none of us saw it.

“It was a nauseous feeling. Success was so close, but now! ‘About ten minutes fuel left, Tom, maybe less.’ Major Witzenburg reminded me. No way to ask for help. Perhaps that field we passed is still open. I started a wide turn to the left, retracing our flight path northward. My mind began racing and settled on tactics instructors stressed on me back in flight school. Never, but never, attempt an emergency landing at night in open terrain. Last resort. Set the autopilot on a heading for the sea and bail out. Then another sorely needed bomber will have vanished, but our personnel’s hard work would linger long in the remorse of failure.

“While we were pondering the next move, another sweeping left turn brought dim winks below. Many moving, dancing flickers barely visible.

“Lights? There shouldn’t be any here, total blackout has been a way of life in the UK for years. Then someone said, ‘We’re over Norwich.’ Barely over it, however, at 200 feet. Flashlights, carried by pedestrians, were reflecting on wet pavement in the city and resembled countless darting fireflies.

“At that moment of realization I became petrified. Norwich Cathedral’s spire is jutting up somewhere, 315 feet high. Pull up, get some more altitude fast!! Too late. It just flashed by while we watched. All this in a matter of seconds, but I well remember the unique feeling of simultaneous fear and relief.

“What now? I held the gentle left turning course. A single amber light that should not be burning. But we passed one, no doubt, and there stood another on our present, unaccountable heading. I didn’t correct even two degrees. Then a third popped up. We knew it had to be the night approach lane of the 458th Bombardment Group at Horsham St. Faith, just north of Norwich. Those lights were glowing in strict violation of security regulations (without 458th aircraft aloft). Why? How? Who was responsible?

“I held my course and began reducing airspeed. The field? No telling how far away it is, and we could only see each light as we passed over. Think, Tom, don’t lose them, I told myself. Be careful, no fouling up now and we’ll get this bird down safely. But I could only do what I was doing. Yet we kept perfectly aligned in the landing pattern, at the correct altitude and were led beautifully by those radiant approach beacons. Check list . . . reduce throttle, lower flaps, increase propeller pitch and gear down.

“Lord keep me from a bonehead mistake now. Airspeed? I heard Miller shout, ‘Hell, I can’t even see the instrument panel anymore, let alone the indicator.’

“Well, I just played it by ear and the seat of my pants. No matter, our moves were already made when the last approach light slipped under. Full flaps. Airspeed seems okay, no stall warning buzzer yet. I would set her down regardless, there was no chance for a second try.

“The feel of the aircraft was perfect as some green lights at the runway’s end cropped up. Then came the cake’s icing – strings of gold plainly marking either side of that precious tarmac. The Lib’s speed and altitude couldn’t have been better if we had followed Consolidated’s technical manual to a tee. She seemed to float onto the field from out of that black wetness to a nose high landing.

May 1944: Yankee Buzz Bomb on a Horsham hardstand

“We taxied over to the flight line to questions and more questions. Then some missing links began to come for us. When we flew over Attlebridge, they saw us and since no one was supposed to be flying, it caused quite a stir. The tower controller on duty recognized those red and white tail markings on our ship to be from the 458th Bombardment Group. Also, he very alertly surmised tour probable encounter with weather and darkness, then assumed we were trying to find Horsham St. Faith.

“Our benefactor phoned the 458th control tower to report one of their planes had just passed over and suggested they turn on the approach runway lighting system. It took a good selling job on his part we learned, as the 458th people thought he was ‘flak happy’.

“Sergeant Harold Perry of Durham, North Carolina, insisted, ‘I’m positive, none of our aircraft are flying today.’ But after more persuasion, he agreed to switch the lights on for a short time, just in case.

“I was a young pilot then, highly trained and finely honed in extraordinary pilotage. Usually, the job was no problem for me. However, against the obstacles the three of us faced that day, all of my qualifications and skills were inadequate for the task. But much to my disbelief and certainly the relief of my crew, we ‘four’ landed safely. Those esteemed flight instructors back at school never once gave an inkling that someday when I least expected, God would be flying with me incognito.”

Southrepps and Antingham School

A school boys recollection of WW2 – Derek J Grey

Derek was born in 1934 in Upper Street, Southrepps. From the age of 5 he attended the school in Lower Street. At that time there were about 160 pupils who walked to the school from the surrounding villages. At that time this part of Norfolk was quite isolated and self sufficient. Most of the grown ups worked on the local farms or for businesses providing local services. In villages such as Southrepps and Antingham there was no mains water, no mains drainage (outside toilets!), very few homes had a telephone and not many people owned a car.

Derek recalls that part of the children’s daily routine was to fetch and carry water pumped from the drinking water wells scattered around the village for their own homes and for their elderly neighbours often before they set off to walk to school.

By early 1939, preparations for war against Germany were already under way and parts of the North Norfolk coast were being fortified with defences against aerial bombardment and invasion by the Germans. Across the county, new airfields were being built and others extended for coastal defence. Troops were billeted in the villages and many of the younger men were expected to be called up for military service. Those not so young were enrolled into the Home Guard. Large concrete blocks were placed across the roads and soldiers manned checkpoints. At the height of the war much of the coastal zone became a restricted zone and non residents required permits to travel into the area.

On 3rd September 1939 Great Britain declared war on Germany. Even before that day, a plan to evacuate many thousands of school children and their teachers from the industrial towns to rural areas well away from the supposed threat of German bombs was underway. On the very day that war was declared, evacuee children arrived in the village. Derek recalls that as he was standing at his garden gate in Church Street, Captain Grey, the local taxi man came up the street in his taxi full of children. He stopped at the house and shouted to his parents asking if they would take in one of the children. Derek’s father agreed and a young boy called Ronnie Clarke was left off at the house. He soon settled in.

Life in the village for young people at that time was very different from today. Whilst the living conditions were not so easy, there was no shortage of good food and there were lots of things to do. Soldiers were billeted at The New Inn (now Ham House) in the High Street so the pubs and shops prospered and there were new friends to make all the time.

The German invasion never came to pass but this part of Norfolk was not immune from the effects of the war in the air. The skies were regularly infiltrated by German aircraft attacking airfields and allied aircraft returning to their bases. Aircraft from RAF airfields across the county passed over the village on their way to targets on the European mainland. Fighters patrolled the skies. Many aircraft encountered problems on the way or suffered damage, forcing them to limp home across the North Sea. Many did not make it and crashed into the sea or were forced to land in the fields nearest the shore.

Derek and his school mates witnessed these events at first hand. As children they were isolated from the real horrors of the war but their parents were always aware of the tragic events taking place in this country and across the world including the death, injury and capture of friends and family members.

A number of incidents occurred in the village witnessed by Derek and his schoolmates.

In November 1943 an American B24 Liberator crash landed at Frogshall Farm towards Northrepps. On that day Derek and two or three other boys were near Lands Pit by the Church. They saw the plane flying low over Lords Green Lane heading eastwards, probably trying to ditch in the sea at Sidestrand, but it fell short and crashed into a Kale field. It skidded across the field, across the Northrepps Road and ended up by Two Gates Lane. As it crossed the road, the wingtip hit a lady cycling along the road.

First on the scene was Peter Drury, the local Baker (the bakery and shop was in Chapel Street, Upper Street where Doreen Bird now lives). He administered first aid to the cyclist and probably saved her life as she was badly hurt. One member of the crew was trapped beneath the damaged plane and two local men, William Riseborough and Jimmy Fox dug a pit beneath the plane to free the injured man.

The Liberator 41-29168F was from the 44th Bomber Group based at Shipdham. It was damaged during a raid on Bremen in Germany and was out of fuel when it crashed. In April 1944 a B17 Flying Fortress crash landed across the Trunch Road just past The White House (the house built by Claughton Pellau the famous artist). The plane came down hitting a big Ash Tree and broke up scattering wreckage over a wide area. The crash site was quickly sealed off by the military. All of the crew were killed. The plane was from the 457 Bomb Group based at Glatton in Cambridgeshire.

For small boys such crash sites were exciting places. Of particular interest were fragments of broken cockpit windows which were made from thick clear Perspex, a new material that could be cut and shaped to make all sorts of things.

Later in 1944 in October, another Liberator made a forced landing in the village. The aircraft B24 41-29340-N was from the 458th Bomber Group based at Horsham St Faith. The plane had been with a flight of twenty-nine B 24’s over the North Sea en-route to bomb the Rothensee oil refinery at Magdenburg in Germany. The plane lost power in two engines and was forced to return home. During the flight, the bombs on board were dropped into the sea but the pilot forgot to open the bomb bay doors so the plane was disabled causing tremendous drag and using up their fuel so that they had not got enough to get home. They managed to make land near Cromer. Seven members of the crew bailed out using their parachutes leaving the pilot, co-pilot and flight engineer to land the aircraft.

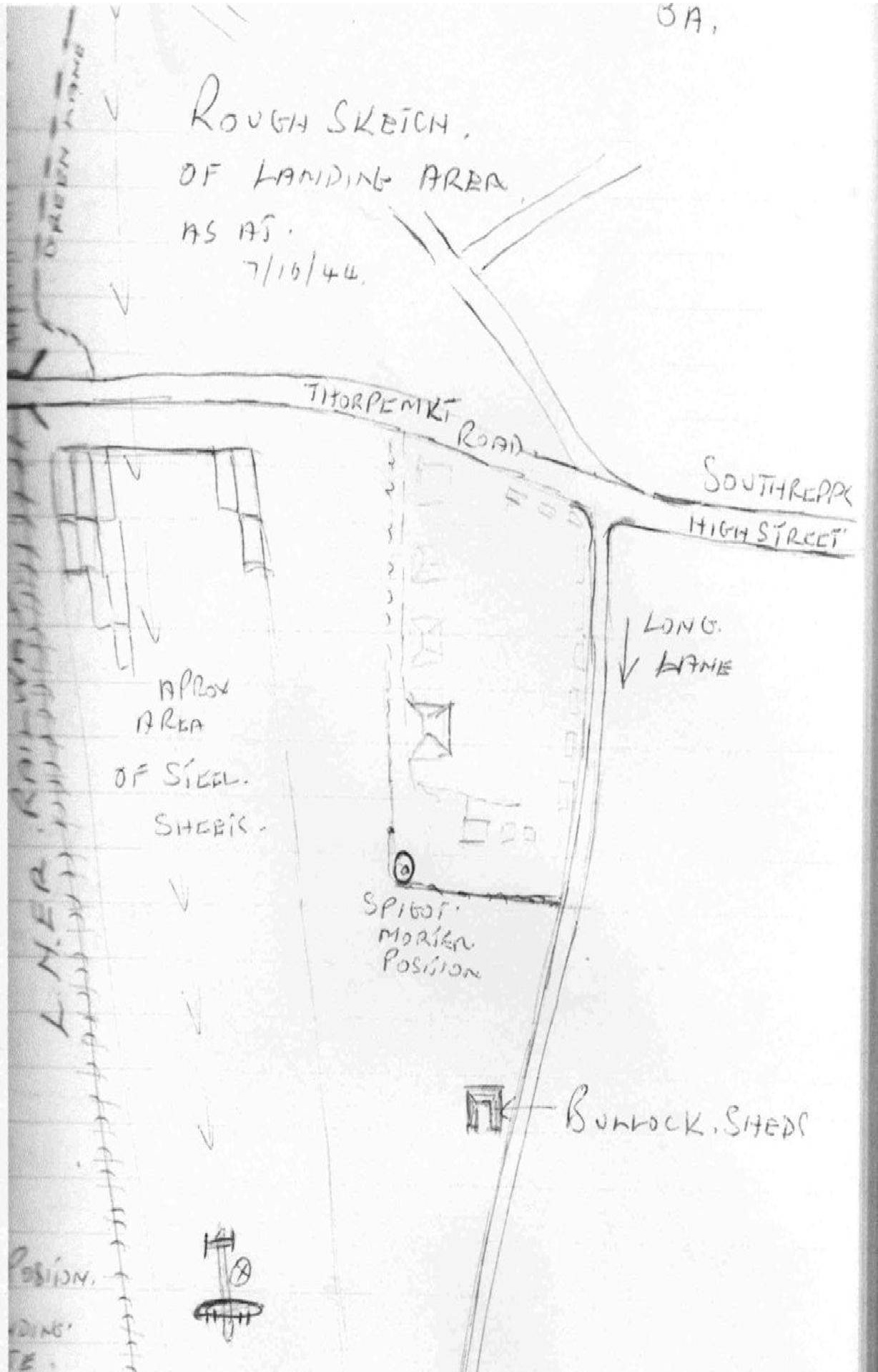

It was a Saturday afternoon at about 2.00pm. Derek and his mates were walking along Green lane towards Brettis Bridge (the railway bridge over Thorpe Market Road). The plane flew low over them and disappeared from view. They ran the length of the lane, down the bank, across the road and up the opposite bank. About halfway across the field on the other side of the bank there it stood. Two of the crew were standing on the topside of the plane. It had been a perfect landing in the stubble field. During the day news came in that other members of the crew had been located. All were accounted for except one. He was Sergeant Edward J Mire, his parachute failed to open and his body was recovered much later from a field in Suffield. There is a commemorative tree in Long Lane (part of The Avenue of Remembrance) dedicated to Sergeant Mire. [See sketch below, click for larger image]

The American Air Force decided that as the aircraft was not badly damaged, it could be flown out. A temporary runway was built across the field using interlocking steel sheets. All these preparations took several weeks during which time many of the American workers stayed in the village. This was an exciting time for everyone including the children. After school they would visit the work site and talk to the American Gl’s. They had sweets and gum and other goodies which were not available from the local shops. The aircraft was flown out on 17th November.

The eventful story of the flight out as recalled by a member of the crew is told in an article from a Flight magazine entitled Cloistered Cockpit. Many of the older people still living in the village remember this incident and many witnessed the take-off. Derek was not among them as he thought the sound of the roaring engines was just another test run and he did not go to the field to see it off.

Other crashes in and around the village included a P51 Mustang of the 355 Fighter Group that crashed in a wood near Tylers Bridge, Southrepps; a B24 Liberator at Bakers Farm in Sidestrand; and an RAF Wellinton that crashed into the railway bridge at Hungry Hill. A Halifax bomber crashed in Bradfield close to Bridge Farm. In all these incidents the aircraft crews-were killed.

A happier ending occurred when a Spitfire crashed in the big field above Hill House Farm on Pit Street. The plane was upended as it landed but the pilot managed to get out. No one was around so he walked with all his equipment up pit Street, past The Stump Cross and into the village. Surrounded by the local children including Derek, he walked into Williamsons shop (the Post Office) and asked to use the telephone to report his bad luck and get some help to recover the plane.

As well as crashed planes the village was bombed and strafed by German bombers and fighters. Every house had a bomb shelter in the garden. Many were Anderson shelters issued by the government.

Bombs fell across the fields in Upper Street including one which unknown to the village had a delayed action. Crowds had gathered to examine the bomb craters after the incident. Fortunately the one that had the delayed fuse went off in the night when everybody had gone home. Other bombs were dropped near the Bradfield Road. The railway bridge across the Thorpe Market road was attacked and Derek remembers that the road signs warning of the low bridge had bullet holes in them for many years after the end of the war.

(Submitted by Colin Needham)

Eastern Daily Press – February 10, 2016

Derek Grey with some of his research

Memorial Lane – Southrepps

Can you help trace family of wartime US airman killed in Norfolk B-24 Liberator drama?

It was the afternoon of October 7, 1944 that the war came closest to the village of Southrepps, near Cromer.

Derick Grey, a ten-year-old schoolboy, was walking along Green Lane with friends when a stricken US B-24 Liberator swooped low over their heads and disappeared from view. The children raced after it and saw it had landed in a field, south of Thorpe Market Road and to the east of the Norwich-to-Cromer railway line. Two crew members were standing on top of the aircraft, a third was safe inside. Police soon arrived, the area was cordoned off and the children shooed away.

The other seven members of the crew had bailed out. Of them, six had survived, but the parachute of one – Sgt Edward J Mire, a gunner – had failed to open. His body was found later, six miles away, at Suffield. Two of the aircraft’s four engines had failed as it headed for a raid on Germany, forcing the crew to make an emergency landing. But, remarkably, those who remained on board managed to execute such a text book landing that the aircraft – “Buzz Bomb” – while in need of repair, remained salvageable. All that was needed – apart from the repairs – was a runway to get it back in the air. So the Americans descended on the village and set about building one. Over the next six weeks, a temporary runway was assembled out of steel sheets. Initially, it sank into the mud, but, once straw was layered underneath, was strong enough to get the bomber airborne once more and back to its 458th Bomb Group’s Horsham St Faith base.

Mr Grey, now 81, and of Cradle Wood Road, North Walsham, still has vivid memories of the crash and its dramatic aftermath. Over the years he has researched it extensively, but has one loose end he is now trying to tie up – to track down the family of the tragic gunner, Sgt Mire. “That was an exciting time for us boys,” he said. I can still remember it all. But now, I would really like to know that Sgt Mire’s family knows we haven’t forgotten him.”

About 20 years ago, Mr Grey told the story to Peter Sladden, owner of Southrepps Hall. Mr Sladden had established a Memorial Avenue of trees along the village’s Long Lane, commemorating local people lost in the two world wars. And he was happy to add another tree, in memory of Sgt Mire. A service of Remembrance is held at the site every year.

But Mr Grey is troubled that any family of Sgt Mire, probably living in the USA, will be unaware that their relative is honoured and remembered in north Norfolk. He is hoping that publicity will lead to the story getting mentioned on websites and through social media, and that it will eventually reach anyone who knew, or is related, to him.

He recalled the excitement he and his friends felt as the US descended on the crash site. Mr Grey remembers cycling past now and then and asking “Have you got any gum, chum?” He added: “They were ready for us and always gave us what they called ‘candy’.” On one occasion, one of his friends invited a GI home for tea, and Mr Grey went too. “We all sat down and, just before we were about to start, he said: ‘Just a moment. We will say grace before we eat.’ I’ve never forgotten that,” he said.

The B-24s engines were often tested during that period but the young Derick knew, as he sat and ate tea one Sunday, that the noise he could hear meant the aircraft was taking off. He raced to watch and caught a sight of it, lifting into the air and heading towards the railway line and Gunton Station.

Images Submitted by: MARK BULLIMORE

Click for article

Update – February 15, 2016

The article above was shared on Facebook and quite a number of people commented on it. One gentleman, Robert McHugh, located the brotherof Edward Mire in Louisiana. I called Robert Mire that evening and he was pleasantly surprised to hear of the article about his brother after all this time. Mr Grey has been given the contact information for Robert and hopefully they will speak soon.