458th Bombardment Group (H)

Mission to Koblenz, Germany

October 9, 1944

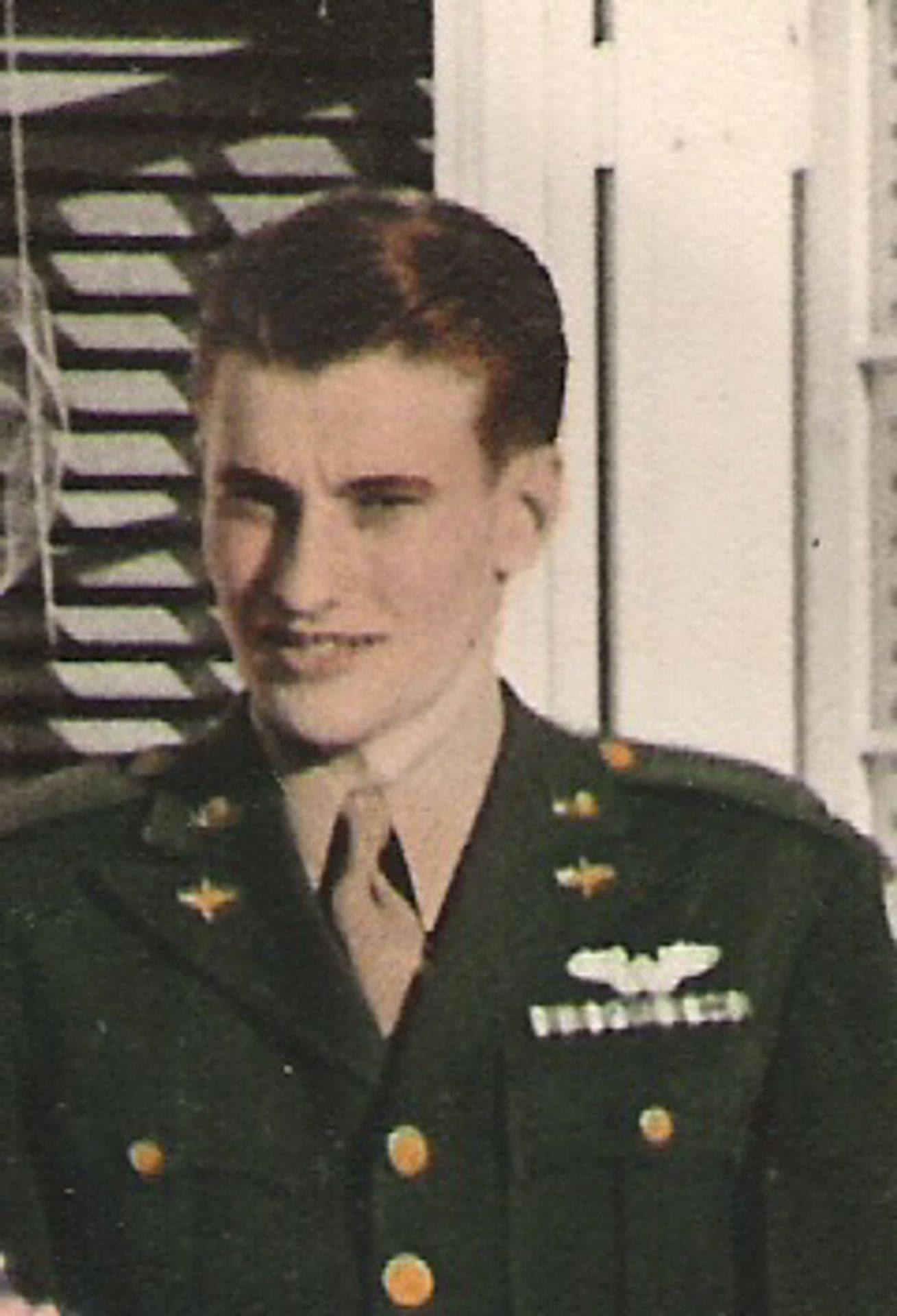

2Lt Richard L. Lougee – Navigator 752nd Squadron

Richard L. Lougee was born 17 May 1921 in CT. He became an AAC cadet in 1942. 2Lt Lougee was assigned to the 752nd Squadron as a navigator on September 19, 1944. Among his decorations was the DFC, awarded in recognition of his service as a lead navigator in raids with the 458th. After the war he joined the Air National Guard and was recalled to active duty in 1951. He left active duty in 1953 and ended his service in the AF Reserve with the rank of Major. His postwar career was largely in the defense industry. He died 4 August 2004; just a few weeks before the death of his 458th Bomb Group CO, Gen. Jim Isbell.

Richard Lougee wrote the following account in the late 1990’s. This material was compiled by Jeffry Burden of Richmond, Virginia with the kind encouragement and assistance of Maj. Lougee’s daughter, Joan Lougee Orris, also of Richmond.

October 9, 1944 mission to Koblenz, Germany

It’s 9 Oct 1944. I’m in the lead B-24 leaving England for Germany. It’s still dark on the ground but as we gain altitude it lightens, but not much, not until we climb above the clouds, which are thick. 1944-45 was the worst winter in Europe in recent memory. The first question we ask the clerk is how much gas [we] are hauling. He has no idea where the mission will be, but he knows how much fuel we are packing. Today, I have no memory of what the specific numbers mean, but then the number told us whether we had a short “milk run” or the other extreme “big B” or beyond. Today is a good haul but not the maximum.

As we get over channel we hit our cruise altitude close to 24,000 feet which is the limit allowed for B-24’s (B-17’s it’s 30,000) – very high in those heavily-loaded bombers. We are still flying a rather loose formation to minimize the chance of mid-air collision. We are prepared. Whenever we hear over the radio or inter-com “Jerries 10 o’clock high” our 24’s cuddle up like lovers on a cold night, wing tip to wing tip often only a few feet apart with the pilots sweating and straining to avoid the slightest movement from course. That’s not my problem, I only have to be the eyes for the whole group of planes following.

On Oct 9 we did not encounter any enemy a/c. As we headed toward the assigned target it wasn’t going to be easy. It was a solid cloud coverage and was not expected to clear the rest of the day or for the days ahead. During the night intelligence and operations prepared our route to the target assigned us by the 8th AF Hq. They not only had to get us to the target they wanted to get us there alive. They had plotted it to avoid as much anti-a/c (flak) as possible. We were the lead ship. The pilot, a capt, the co-pilot a senior officer, usually a Lt. Col, or on important missions our CO Col Isbell, a wonderful commander, an all-American tackle from West Point. The chief Navigator, a lieutenant, soon to be promoted to Capt and the bombardier also soon to be promoted. As a lead ship, [there were] more [on board]. Besides our pilot, nav, and bombardier, seasoned veterans, we had the Colonel on board and two more navigators. In the nose gun turret, normally occupied by an enlisted man, we had another navigator, pilotage navigator, who could give visual positions to the main navigator. That day, as in most instances in 1944-45 his duties were restricted to taking a ride and watching for enemy a/c.

In late 1943 the 8th AF started getting a/c modified for radar. By today’s standards it was model T. Very primitive and very apt to malfunction. Whereas today our electronic gadgets can almost tell the exact position of relatively small objects on the ground, in the latter part of 1944 when our radar became operational, the city the size of Berlin would appear on our 8” scopes about the size of the end of your finger.

OK, on 9 Oct the only eyes that the 458th bomb group had was my little black box in front of me. That was also the only eyes that the 466th and 467th BGs following us had. One of the groups, I forgot which one did not have radar, and the other group’s equipment had malfunctioned.

My little box was just as good as my ability to interpret the scope. I was less than a year out of Navigation school, and had about 3-4 weeks of radar training. I was the youngest officer on the crew except the pilotage navigator who was probably about my age. Of the enlisted men the engineer and radioman were older than I, the rest younger. We carried a crew of 11, as compared with ten on other ships. In place of the belly turret we had a radome which had to be cranked down after takeoff and up before landing.

458th Bomb Group formation

Photo: Mike Bailey

As we head off to the target, we have reached altitude and have been on oxygen for some time. Besides heading for the target we have another object, avoid flak. Our route has been carefully plotted in order to avoid anti-aircraft. I constantly call off coordinates to the navigator and give course changes to the pilot. Picture it, a group of 27 planes being directed by me, and two other groups following, I didn’t know that then, best I didn’t. Think about it, remember when you were a kid skating and playing something like snap the whip or something. The pivot guy stops and the ones on the end have to go full speed to keep up. Now picture the lead ship, planes behind him, some to the left, some to the right, some a few feet above and others a few feet below, all spread out thousands of feet. A left turn and those inside have to slow down being careful not to stall and the outside applying max power burning excess fuel. [A] turn of more than a few degrees results in chaos. Thus, I had to make sure that I stayed on course in order that I didn’t have to make corrections of more than 3 or 4 degrees.

We head for the IP, Initial Point where we start the bomb run. We’ve plotted and hopefully flown such that we reach that point and head for the target without having to make any but small course changes. We start on the bomb run. Based on prior data the bomb sight is flying the air plane. I call to the bombardier, 15 miles to the target, 14 miles, etc., the bombardier sets that info into the sight. Based on my information, the navigator calculates the true direction to the target, rather than just the compass heading. By now he has given all of his calculations to the bombardier and he has entered it into the sight. As I keep calling miles to the target, adjusting my equipment for shorter span thus enlarge it I hope to get to ¼ mile (very fortunate to get it to ½). We’re all praying that there will be a break in the clouds in order that the bombardier can take over and bomb visually, or at least long enough to make a more accurate adjustment to the sight. On Oct 9th that did not happen, we hadn’t seen the ground since we took [off] from Horsham St. Faith AFB many hours earlier. Finally, with all the available data entered into the bomb sight, [we] dropped our flares and those behind us their bombs.

We had intervolmeter settings for our bombs. On clear days when the bombardier could be more accurate we had low settings, having the bombs dropped into a more precise area. On days when we were not able to accurately pin-point them we had high settings, thus spreading the bombs farther apart.

On 10/9 we spread them out. We headed for home, I no longer worried about not messing up, we worried about getting home. The first half of the mission was for Uncle Sam, the last part for us.

We had no idea how accurate our drop was. Several days later photo recon was able to get a picture. We had knocked out the target, marshalling yards at Koblenz, Germany. However, because of the large area covered because of the need to spread the bombs we also hit what was to be an apartment house or homes. Among other reasons why I was glad I was in the AF was because I never knew who if any were injured or killed. I just hope that they all made it to the bomb shelters.

Note: I had no intention or thoughts of writing this when I started. Almost magically these thoughts, many of which I had forgotten, came back, especially these minute details. I have been aided by my own war records and I have a copy of the Mighty 8th War Diary. On Oct 9, 1944, 384 B-24’s of the Second Bomb Division [went] to that target, 360 made it to the target. We lost 1 a/c to flak, the others having to abort for some reason, probably mechanical. The war diary stated that all of the 8th made PFF (Pathfinder Forces) on industrial targets in south and central Germany. Counting all dispatched that day by all 3 Bomb Divisions of the 8th, B-17s as well as B-24’s there were 1110, 1049 reaching target.

That was my 2nd mission. The first was three days earlier, Oct. 6. According to my records and the diary we went to Wenzendorf. I have absolutely no recollection of that mission. It must be true, the records say so.