458th Bombardment Group (H)

A Day in the Life of Aviation Ordnance

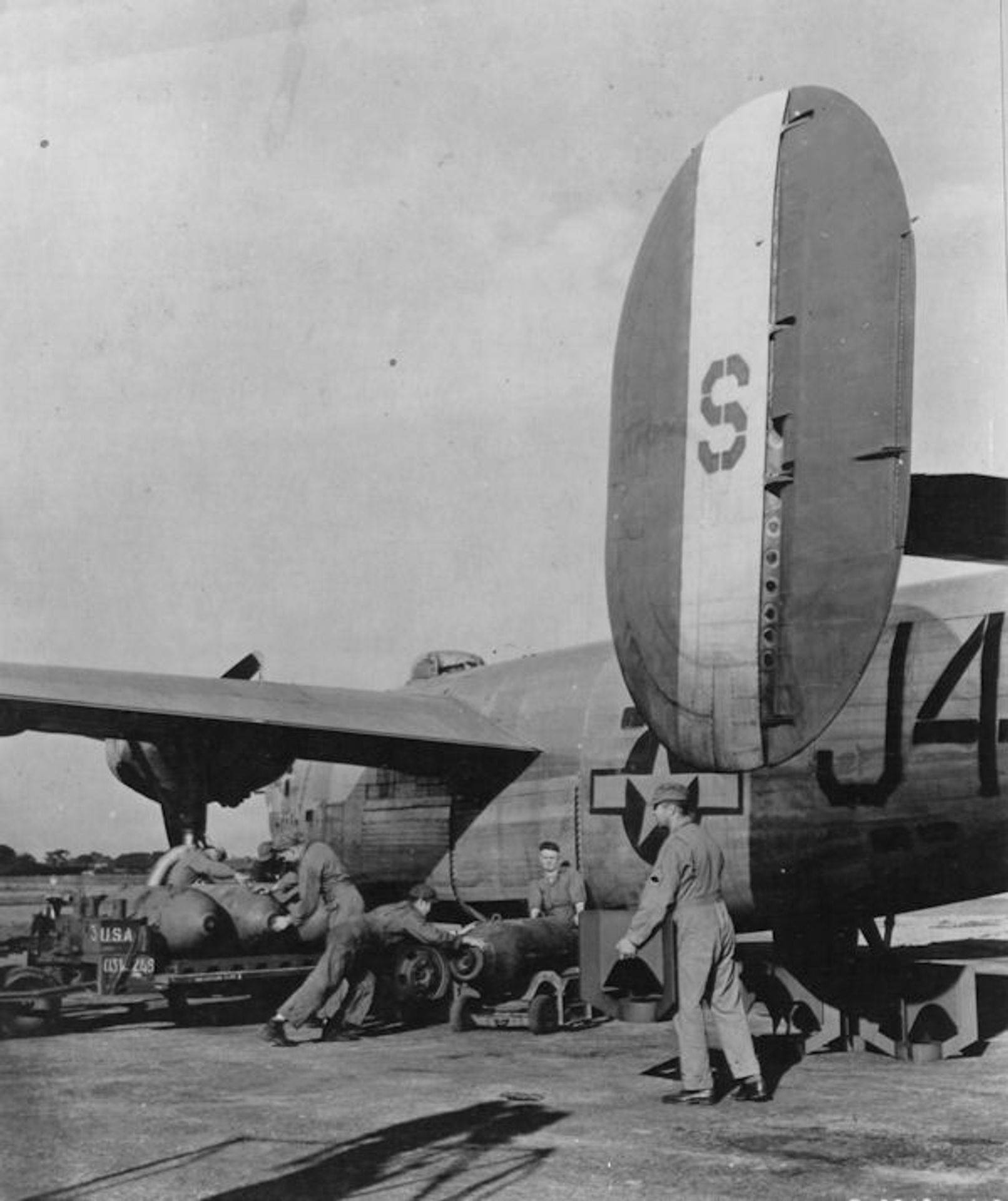

754th Ordnance at work: Charles V. Smith (with bomb fin), Ben Hooker (pushing bomb dolly), Harry Black (pulling bomb dolly), Arthur Giroux (fusing bomb).

(Photo: FOLD3)

It is late evening, May 7, 1944, and the second shift of the 754th Ordnance is reporting for duty. The 754th is part of the 458th Bomb Group (H) stationed just outside Norwich, England. The ordnance office is a little cubicle located along the side of the big hangar near the control tower. As we enter, the clerk doesn’t look up from his typewriter, for he knows that someone will ask the inevitable questions, “Have we been alerted?” or “What is the bomb load?” Most of the time he doesn’t know any more than we do, so his answer is usually meant to deceive. If we can find out the type of bomb load ordered we can speculate on the target, or at least the type of target.

As the day crew has cleaned up most of the work, a few of us drift down to flak suit storage under the pretext of checking their condition, but actually to goof off more than anything else. Someone decides he is hungry. We ante up the shillings required to send for a few pounds of fish and chips, and he slips out through a hole in the fence and comes back shortly with a bundle wrapped in London or Norwich newspaper.

Flak suits are just about as popular with the air crews as car seat belts are now. Pilots (particularly new ones) usually sat on them until a heavy barrage ventilated the cockpit – then they had a change of attitude. It is our job to place one for every crew position.

At about 2200 hours the order comes down – mission is on, and a lot of work by a lot of men is required this night before the big birds can fly. Of course we still don’t know where the target is, but we later learn that it is Brunswick. Bomb load is 12x500lb GP, with M-103 nose and M-106 tail fuse, instantaneous. All crews mount their bomb service trucks (BST) and race to the bomb storage area. Since all four squadrons are vying to be the first to load, there is some confusion and traffic congestion. After a wait that seems interminable, we are finally loaded with bombs, fins, fuses and other accessories required to put together a bang big enough to ruin Her Hitler’s day.

The big birds (B-24’s of the 754th) are sitting on the hardstands waiting on the eggs to be loaded. Each bomb is moved by dolly to the bomb bay, hoisted and attached to the shackle, fused, arming wires attached, and safety pins checked and tagged. This is repeated until all aircraft are loaded. My notes indicate that A/C #276 is already loaded from a previous mission, probably aborted. Normally if a mission is scrubbed, all bombs must be removed and returned to storage, making double work.

Dawn is just breaking as we finish the last plane, and it won’t be long until pre-flight and then the air crews show up for the day’s business. We head for the mess hall and some hot chow, and then to the barracks for some “sack time”.

I’m just barely asleep when one of the day crew awakens me to inform that one of the planes we just loaded has crashed and burned on takeoff. It is Belle of Boston, A/C 42-52404, and the pilot is Lt. Paul Kingsley, my cousin. I can’t get back to sleep, so I sit on the side of my bunk and smoke a cigarette. I have previously witnessed crippled bombers coming in and the customary red flare arcing skyward indicating wounded on board, but for the first time I’m really aware that people are being killed in this war.

I attend the military funeral for Lt. Kingsley at the Cambridge Military Cemetery, and later, when his body is brought back to the States, I act as pall bearer at a second burial service. Paul is buried in the same cemetery where my father and mother are laid to rest. When I visit the cemetery, I invariably gaze at the 8AF insignia on his grave marker and I’m transported in memory back to the date also inscribed there: May 8, 1944.

Article: Ben Hooker, 2ADA Journal