458th Bombardment Group (H)

Rocket-Site Raiders

Colin Bednall [pictured right, post war], young Daily Mail Correspondent, to-day puts up his seventh private “battle honor” by accompanying a Fortress [sic] raid on the heavily defended secret weapon sites in the Pas de Calais. After this raid, Southern England yesterday had its longest lull for some days from flying bombs. Previous operational flights made by Bednall include Berlin, Leipzig, St. Nazaire, Northern France (two) and Normandy on D-Day.

From COLIN BEDNALL. Air Correspondent

Back at A U.S. Eighth Air Force Station, England, Sunday,

This, the biggest air force in the world to-day, broke through a mountainous cloudbank which had barred its way into the Pas de Calais area for several days, and delivered one of the most comprehensive attacks yet made on the German secret weapon platforms there. I rode with the battle wagons – in the waist-gun position of a Liberator which, in a long, unchecked career, has spanned the Atlantic and the road to Berlin – the latter several times.

An interesting gauge of the enemy’s values just now is the fact that the Pas de Calais area has become one of the hottest spots in all Europe for the bomber. The Luftwaffe does not dare show its fighters at a point so close to the Allied fighter bases, but it has stacked the area with an amazing number of ground guns and anti-aircraft rocket devices. These rockets are not fired in salvos, like ours; they come up singly but, curling like evil snakes, they rise to an immense height. From my Liberator window this afternoon I counted at one moment a dozen of these rocket trails.

The formation I flew in was a very small one by American standards. We were sent to an especially high altitude – the highest I have ever experienced. The ground guns showed that they could find our height and higher still if need be, but they never managed to put their shells or their rockets in the right place at the right moment. The strength of the ground defences massed in the Pas de Calais area is so great that crews now are often under constant fire from the moment they reach enemy territory until they leave it. The enemy cannot often bring the bombers down. But with the use of experienced gunners, he can often hit the plane and maim the crews. That is something the public seldom hears about.

His object to-day was to throw them off their aim when they dropped their bombs. The flying bomb platforms present by far the smallest target ever consistently attacked by the bombers. With almost incredible consistency, the weather favours the enemy by stringing cloud across the targets. I can vouch for the fact that the 8th Air Force to-day made a very determined attempt to overcome all these heartbreaking obstacles. My formation used instruments to beat the cloud, but until the reconnaissance has been carried out, nobody can say with certainty whether they were completely successful.

It is certain, however, that round about lunch-time to-day flying bomb installations and their personnel were harassed by a rain of bombs likely, at the least, to dampen their enthusiasm. The flak did not deviate the bombers I was with from their bombing run. With immaculate discipline they dropped in great clusters the biggest loads ever carried by the heavily armed bombers. I could see the flak searching the sky for the many other formations which went simultaneously to the area.

Less than a year ago the weather forecast for these attacks would have ruled bombing clean out. Over France we found that the “Met” man for once had actually exaggerated the unsuitability of the flying conditions. The cloud over the target area was neither as thick or as widespread as conditions in the English Channel had suggested. There were gaps through which you could see woods, roads, and villages laid out exactly as they appear in high altitude reconnaissance pictures.

In all fairness to the 8th Air Force, however, I must add that only the use of scientific equipment permitted any sort of bombing attack in the conditions which existed. The crews could not guarantee results; they could only fight off the enemy’s attempts to interfere with the proper functioning of this equipment.

To-day the 8th Air Force had assembled a major force to attack Pas de Calais. We were marshaled in the air, took up formation and turned towards France. Rising in breath-taking majesty above the English Channel was the mightiest cloud formation I have ever seen. Its base was little distant above the water and in one almost unbroken mass which reached right up into the sub-stratosphere. Not even the phenomenal “battle wagons” could climb above it. To fly through its cold, murky blackness would have meant facing icing and disastrous confusion among their formation.

But I have no doubt that if they had been asked to do it the bombers would have flown straight on into that hazardous cloud mountain just as they rode through flak and fighter attacks. I know these American bomber men – their resolute discipline will be legendary in years to come. Screwing my hand around the corner of the waist window, I gaped at the terrifying spectacle of the cloud ahead. My own formation circled in front of the great cloud for some minutes.

V1 Launch site in Northern France and the launch rails that were very difficult to hit

(Photos: Imperial War Museum)

The assembly of a major bomber force in the air is an enormous undertaking – more so in bad weather. Every individual aircraft has to climb through the cloud and find the invisible spot set down for rendezvous. An age seemed to pass as you droned upwards through the eerie loneliness of a cloudbank. Then suddenly, like a train coming out of a tunnel, we emerged into the clear sky. Then, all around, countless other bombers popped out of the undercast. It was a dramatic moment, very reminiscent of that experience over a large target area with the R.A.F. night bombers. A great aerial battle force suddenly emerges from seemingly nowhere. The 8th Air Force had gambled on the weather to enable the force to get through to its objective.

In the great height to which the Liberators had to climb no man could have survived without elaborate artificial aid. Then, as we approached the enemy coast, we opened the panels for the waist guns. There was a rush of icy air. The crews call it a “blast”, and there is no other word for it. It freezes anything in its path instantaneously. It could kill or hurt like the blast from a furnace or the blast from a bomb, so you are wrapped from head to foot in electrically heated clothing. Hardly an inch of bare skin is left exposed.

Condensation of your breath seeping out from behind your large rubber oxygen mask freezes into icicles. You can crack it off like cracking glass splinters. The oxygen supply comes through an ingenious device which automatically adjusts the difference in atmospheric pressure. But at the height at which we flew to-day we were told to periodically turn on pure oxygen. And each time I did so it was like being revived from semi-consciousness.

Air forces have grown so big that the human element involved is often overlooked. So I would just like to set down here brief personal details of the men who were in this one plane of a mighty force this afternoon.

The Pilot – Captain John L. Weber, from Connecticut. He holds the D.F.C. and the Air Medal with three oak leaf clusters. He has flown 28 missions over Europe and been to Berlin four times. He is a graduate of West Point.

The Co-Pilot – Second-Lieut. William F. Smith, from Maryland. He holds the Air Medal with cluster. He has been over Europe 14 times.

The Navigator – First-Lieut. Robert H. Lawrence, from Pennsylvania. D.F.C., Air Medal and three clusters; 20 missions.

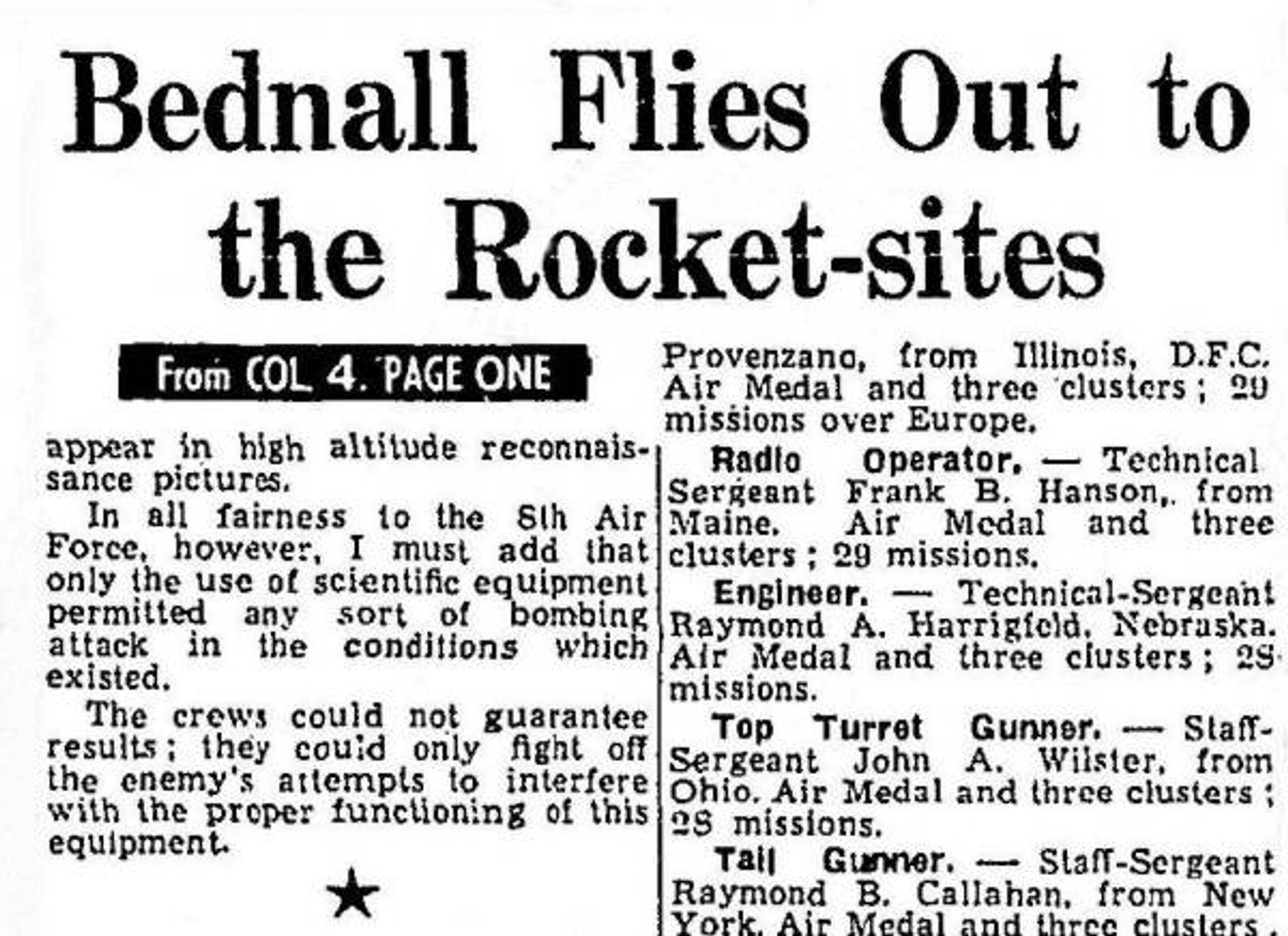

Bombardier – First-Lieut. John J. Provenzano from Illinois. D.F.C., Air Medal and three clusters; 20 missions over Europe.

Radio Operator – Technical Sergeant Frank B. Hanson, from Maine. Air Medal and three clusters; 29 missions.

Top Turret Gunner – Staff Sergeant John A. Wilster, from Ohio. Air Medal and three clusters; 28 missions.

Tail Gunner – Staff Sergeant Raymond B. Callahan from New York. Air Medal and three clusters; 28 missions.

Additional Navigator – First Lieut. Robert E. Clark from Connecticut. Air Medal and three clusters; 20 missions.

And last – but not least as far as I’m concerned – the man who stood opposite me at the right waist gun position – Staff Sergeant Alfred H. Malmstrom, from Louisiana. He holds the Legion of Merit, the Navy Cross, the Air Medal and four clusters. He has flown 22 missions with Liberators. But with the very first contingent of American airmen to reach this country after Pearl Harbour he was assigned to a Havoc Squadron in England. He flew no fewer than 66 missions with the Havocs before returning to America for a short period of rest.