458th Bombardment Group (H)

Pilot’s Memoir – 1Lt Curt M. Vogel

Page 2

Getting back to February, 1944 – we soon settled down to the serious routine of getting the 458th Bomb Group ready to fly combat missions. We were in the 755th Squadron, 458th Bombardment Group, 96th Bombardment Wing (H) and 2nd Division of the 8th Air Force. Our crew number was 74, which we considered lucky since it added up to 11. For some reason the crew considered 7, 11 and 13 as lucky numbers. Bernie Doyle also had a 4-leaf clover, a horseshoe, and also a brick that had the number 13 on it. When asked whether he and the crew were superstitious, he replied “Hell, no, we’re just not taking any chances”. The four officers were in rooms which had been part of a house for the RAF and was better than a Quonset hut. We spent very little time there because of our busy flying schedule. The flying officers had their own mess hall separate from the ground officer personnel. The flying crew enlisted men also had a separate mess hall. The food was good and took into consideration that flying at high altitudes would not allow food that created gas or stomach discomfort. On days we were scheduled to fly a mission, we usually got fresh eggs if we wanted them.

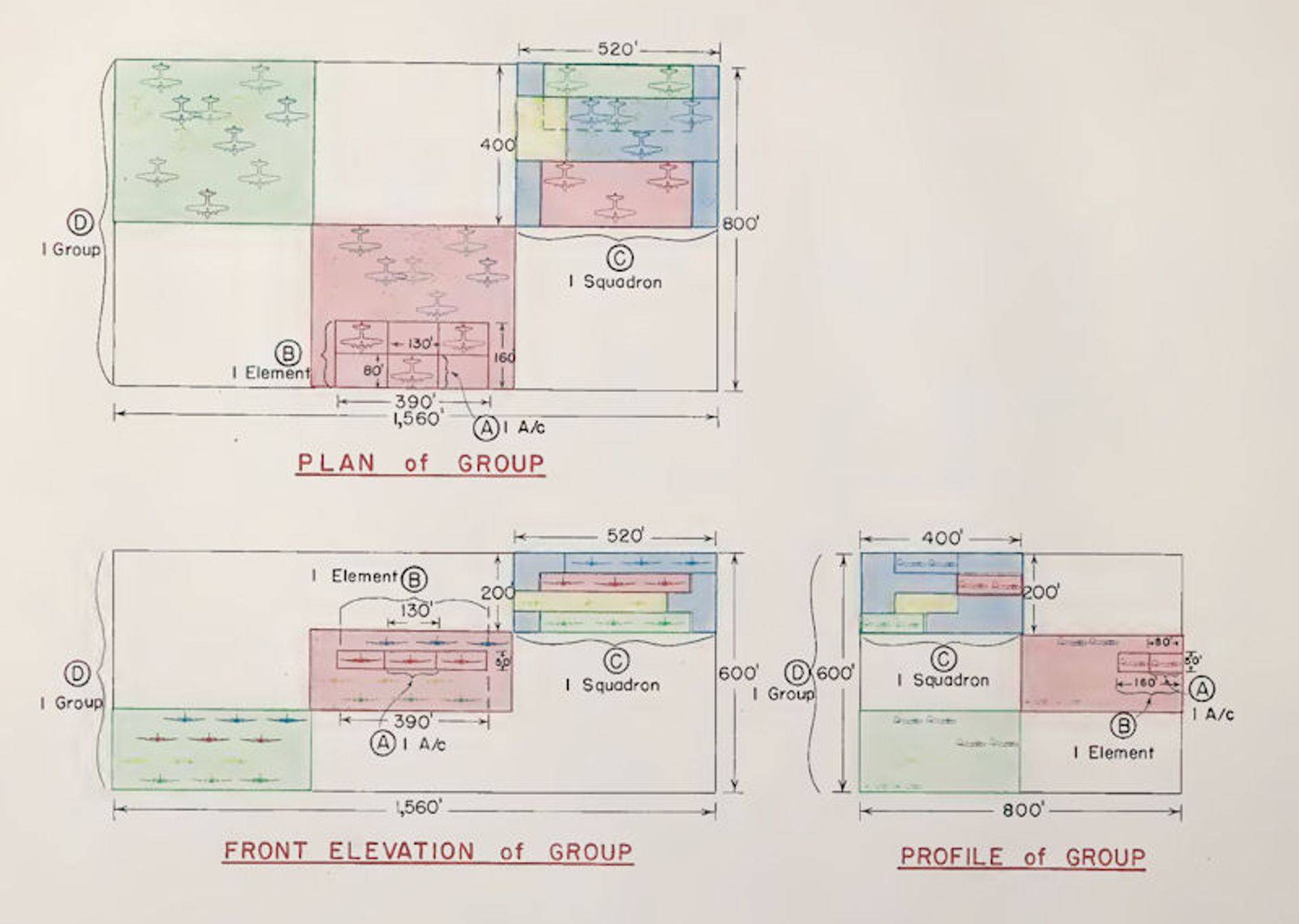

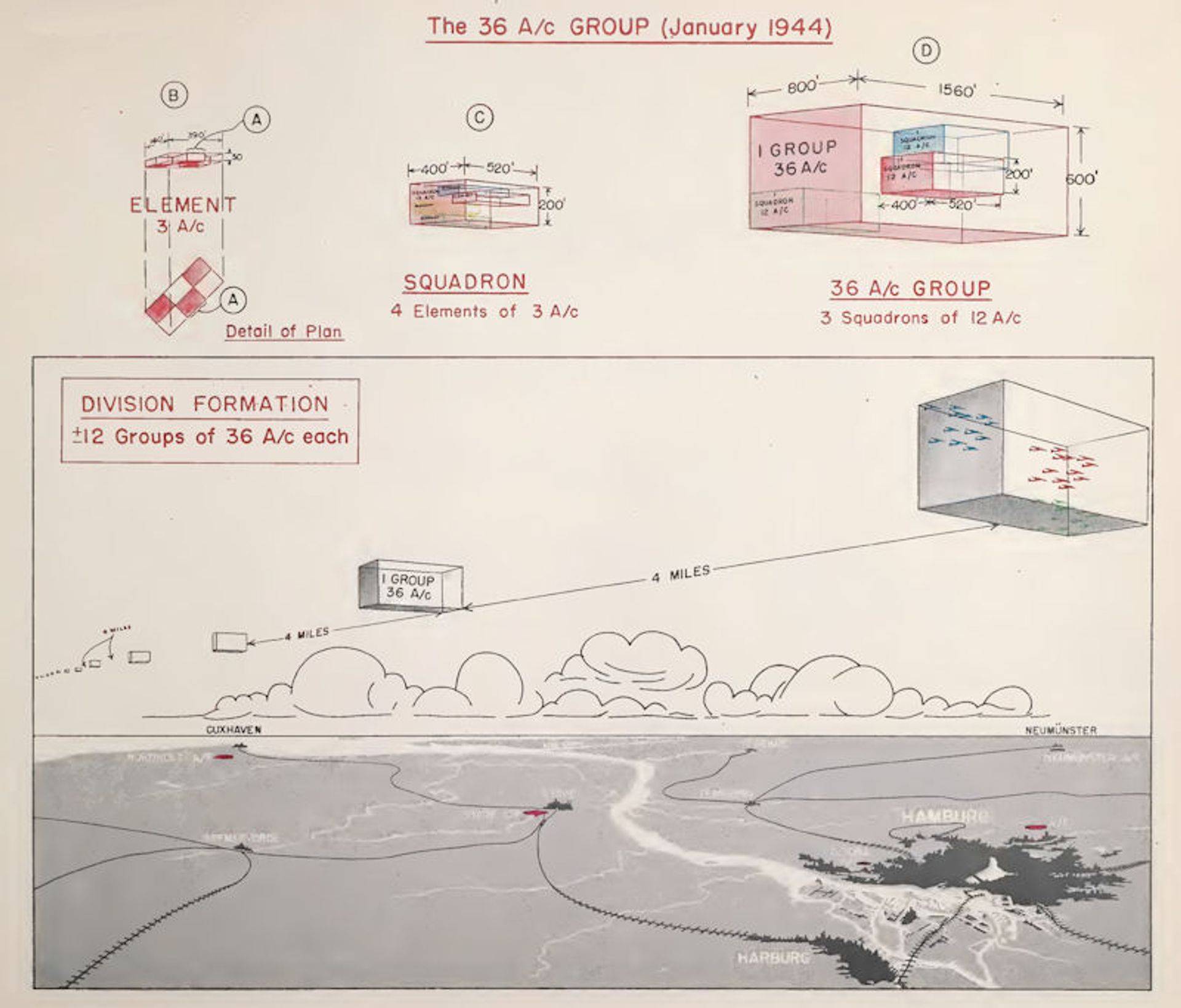

Most of our pre-combat flying was practicing formation flying the way the 8th Air Force wanted it. The formations were in units of 12 planes. Three were in front, three were high and to the right, three were to the left and low, and three were behind and lower than the three lead planes. This was a good formation because it gave the gunners a good view of enemy fighter planes and when the formation had to make a turn, the top three would move over the top of the first three and the lower left three would move over the last three which would give all planes the same radius when making a turn. When the turn was completed, the top and lower three planes would resume their designated positions. In our group we usually had about 24 planes on a mission, a few times a few less and sometimes a few more.

The 458th flew its first combat mission March 2, 1944, and on Sunday March 5, 1944, our crew 74 flew its first combat mission with no losses to Bordeaux, France. This was our first contact with flak (anti aircraft barrage) but no enemy fighters. On March 6 (we did not fly this mission) was the first big raid on Berlin, Germany. The papers reported this as a 1000-plane raid and the losses to the 8th Air Force were listed at 69 planes lost to enemy action. The 458th, our group, lost 5 planes. It doesn’t take much figuring that if we were to fly 30 missions, our survival rate would only last about 5 or 6 missions. Fortunately this was the only such heavy loss for the group. In the month of March the Group flew 15 missions and only lost a total of 9 planes to enemy action. On March 8, 1944, we flew on the second 1000-plane raid on Berlin (actually Erkner, a suburb of Berlin). The flak was unbelievably heavy, and the enemy fighters were out in great numbers. The 8th Air Force lost 56 planes, but our group only lost one plane. Except for some flak holes in the plane, we were fine, but we were fully aware that combat flying over Europe was a hazardous occupation. A list of combat missions flown by us is as follows:

| Msn # | Date | Location | Msn # | Date | Location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 05-Mar-44 | Bordeaux, France | 16 | 04-May-44 | Brunswick, Germany | |

| 2 | 08-Mar-44 | Berlin, Germany | 17 | 07-May-44 | Osnabruck, Germany | |

| 3 | 15-Mar-44 | Brunswick, Germany | 18 | 08-May-44 | Brunswick, Germany | |

| 4 | 21-Mar-44 | St. Omer, France | 19 | 09-May-44 | Liege, Belgium | |

| 5 | 23-Mar-44 | Osnabruck, Germany | 20 | 12-May-44 | Bohlen, Germany | |

| 6 | 24-Mar-44 | St. Dizier, France | 21 | 13-May-44 | Demmin, Germany | |

| 7 | 26-Mar-44 | Aras, France | 22 | 19-May-44 | Brunswick, Germany | |

| 8 | 05-Apr-44 | St. Poll, France | 23 | 21-May-44 | St. Pol, France | |

| 9 | 08-Apr-44 | Brunswick, Germany | 24 | 23-May-44 | Bourges, France | |

| 10 | 10-Apr-44 | Bourges, France | 25 | 24-May-44 | Villeroche, France | |

| 11 | 11-Apr-44 | Brunswick, Germany | 26 | 29-May-44 | Tutow, Germany | |

| 12 | 13-Apr-44 | Lechfeld, Germany | 27 | 31-May-44 | Bertrix, Belgium | |

| 13 | 19-Apr-44 | Paderborn, Germany | 28 | 02-Jun-44 | Stella Plage, France | |

| 14 | 20-Apr-44 | St. Pol, France | 29 | 04-Jun-44 | Bourges, France | |

| 15 | 22-Apr-44 | Hamm, Germany | 30 | 05-Jun-44 | Stella Plage, France |

You will note we went to Brunswick, Germany, 6 times. Brunswick was a very heavily defended city and each time the flak was extremely heavy and we always were attacked by enemy fighters. The missions to France and Belgium were not as rough but if you were shot down, capture by the Germans was almost a certainty since Germany controlled all of Europe throughout our 30 missions. The bomb run was the most dangerous and nerve-racking since you would be flying straight and level through the highest concentration of flak with no evasive action to avoid the flak. Since up to 1000 planes would assemble over England at the same time at about 6000 to 10,000 feet, the procedure was tedious, and costly in time and fuel, and costly also in lives and planes. The official records indicate that about 300 planes -about 5% of those lost to all causes -were lost to in-flight accidents during assembly. The value of the resulting formations, however, was such that for every plane and life they cost, probably 10 others were saved. Personally I saw two planes collide during assembly and as far as I know, no person got out alive.

In regard to the bomb run, I submit something Bernie Doyle wrote 40 years later. The term “bitch”, a GI expression, here means terrifying and frightening.

THE BOMB RUN WAS A BITCH

On this maximum effort mission, formations of B-17’s and B-24’s were stacked up from 22,000 to 28,000 ft. Some Groups were under fighter attack, others were dodging flak. There were bombers going down in any direction you looked. A bad scene to remember but the worst was yet to come.

The real fun starts when we hit the Bomb Run. Straight and level like sitting ducks. No evasive action, just plough on through. Now the flak is really on target. We worked, we prayed, and sometimes cursed. Planes were hit, some broke up, some chutes deployed, most didn’t. Then the words we loved to hear, “Bombs Away” -“Close the doors”.

There were still fighters and flak to contend with and more bombers still dropped out of the sky but we’re heading home with one more memory that the Bomb Run was a Bitch.

When WWII started the country was full of young men with total patriotism and total anger at anyone who would attack our friends and our own ships. We couldn’t wait to set things straight and make our enemy pay. We came from different places, had a variety of backgrounds and personalities. Some were well educated, some were not. Some were rich, some poor, a true Hodge-podge of the country’s youth.

Brown was a kid from Brooklyn. He worked in his father’s gas station and aspired to be a commercial artist. What he wanted out of life was to marry his childhood sweetheart and paint or pump gas. At least that was his limited view before WWII.

Potts, a quiet kid. He didn’t ask many questions or answer many either. We really didn’t know him but he knew his job as a ball turret gunner and performed it to perfection.

Al Hilborn, our rich kid, “we thought”. He was a talented college man, excellent athlete, the Ivy League kid. Stiff and formal on the outside, safe and sensitive on the side we didn’t see.

Our enigma A.J. Testa, a warm sensitive crew member. Always friendly but always seemed to be looking for something. A.J. had the guts of a burglar and the warmth of a priest. I don’t think we got to know him and I’m not sure he knew himself.

Carlstrum, the kid from the high country, an outdoor type that loved to hunt. His youth was spent in an area where a good eye counted. Perfectly suited for his job with the balls it took to be a tail gunner. R.I.P.

Murphy (Murph), we can’t forget him. Young, wild, careless and scared. He tried to be a grown-up before his time. He lost more than his pride before it was done. R.I.P.

Doyle, the other Irishman let you see the part of him he wanted you to see. He knew his job and knew how to drink. If you thought you knew him, you didn’t.

Goldstein wanted to be part of the action so bad it hurt. It hurt so much it killed him. R.I.P.

West, the farmer with the funny front name, “Lovell”. You could depend on him and we did, mission after mission.

Al Walczak, the Polish falcon with a beak of about the same prominence a hard working gunner in the air and on the ground. He took his job so seriously, he lost his breakfast every mission. With Al, “what you saw was what you got”. R.I.P.

Sam Scorza never knew what violent anger was. He was a smart and sensitive guy, played the saxophone and was active in his hometown church offices. Never raised a hand in anger before WWII.

The Old Man, Curt Vogel. He was the Father figure, the Boss, the Coach, the Judge and Jury. He had so much faith in human nature he thought the rest of us were okay. We were lucky to have him. He led us, trained us, threatened us, pampered us, then took us to where the Bomb Run was a Bitch.

Some Supreme Being if he was interested would have looked down on this group and if he had a sense of humor he would have had to laugh, “A deep belly laugh” and then wondered how such a mish-mash of guys could ever be made to act as a combat crew. If he was looking for warriors, he must have laughed again.

Yet, there they were, with hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of taxpayers ‘sacrifices assigned to “take it to Hitler”. Hitler would have laughed too; “At First”. The experiences in the air and on the ground would fill volumes if we wanted to recall them. Some of the ground stories were more exciting and certainly more risqué’ than the air stories. There were many beers and more tears than any would admit–besides–grown men don’t cry. Not where you can see them.

Well, they made it through, this motley crew, not without a price to be paid. The pride, the blood, the lives of those left behind are always remembered. Most times, as is the habit with boys then men now, we laugh and are philosophical about the past. Except in our private times when alone with our thoughts, we sometimes forget, grown men don’t cry.

The most remarkable part of this summary takes place 40 plus years later. The characters at a reunion are some of those mentioned previously. The reunion is taking place in the State of Maine, far from the bright lights this group is accustomed to frequent. No it is not a sanitarium. When the remnants of this crew meet, we’ll drink and carouse. We’ll remember facts and create fiction but I don’t think we’ll forget, THE BOMB RUN WAS A BITCH.

Before we flew our first combat mission, I wrote a letter to the parents of all the enlisted men, except Carlstrum, who was an orphan. The reason I want especially to make reference to this letter is because the idea of writing it and most of the contents were Jean’s idea. The letter was really appreciated by at least three of the parents. The letter reads as follows:

February 20, 1944 Dear Mr. and Mrs. ____: The time will soon come when our crew, of which your boy is a member, will be called upon to do the job we’ve been prepared to do. There are three things I want you, as his parents, to know, hence this letter. First of all, we want you to know that we are glad to have him on our crew because he knows and does his job well. Second that your boy, and the other nine members of the crew, have been given the most complete training possible to prepare them for their work. This of course means that your son has the best possible chance of corning back to you and of doing well his part in this war. Third, that since I have a boy of my own (he’s just a little fellow 16 months old) I realize how priceless a boy is to his parents, and assure you, that as his pilot, I will guard his safety as carefully as I would want my boy’s safety guarded.

Trusting in God for the safety and well-being of our crew.

Sincerely yours, Curt M. Vogel, 2nd Lt. A.C.

(The original letters were written by hand.)

On the day of a mission, we would be awakened about 3 A.M. This was our first and only notice that we were going on a mission. All crew members would get dressed and always shaved because we would have our oxygen masks on for up to 6 hours. We had bicycles to get to the mess hall. On mission days we had good meals and almost always fresh eggs instead of powdered eggs. The whole crew met at the briefing room and no one was ever late on our crew. All the crew members would be in the briefing room a few minutes before the time set for briefing. In the front was a large poster about 6×8 feet, which was covered by a white cloth. This poster had the mission outlined on a map of Europe. The lines were made by a narrow red tape. At precisely the scheduled minute, the commanding officer would enter the room. The first man to see him would call “Attention” then all would rise and remain standing until he had reached the front of the room and said “Be seated, gentlemen”. Then came the dramatic moment when the C.O. after a very few remarks signaled the operations officer to remove the white sheet from the poster. If it was a long mission day into Germany, there would be expressions like “Oh boy” or “Wow” and some moans. At one of the earliest missions, the target was one of the worst and, except for a few groans, it was quiet, but then some guy in the back called out “What do you guys want to do, live forever?” This broke the tension and everybody laughed a little and the briefing continued.

The enlisted men would then leave and go to the plane. The navigators and bombardiers had their briefings and the pilots theirs. All watches were synchronized to the second. The co-pilot also picked up the escape kits for all crew members, in case we got shot down over Europe. You can see that all the crew knew where we were going and what kind of target we were supposed to hit and hopefully destroy, and get back alive.

The Chaplain was always present and said a short prayer. Even after the briefings, missions would be cancelled, usually because of changes in the weather from the time of the earlier forecast. It was about I hour after briefing before we actually took off. The mission required a day when England’s morning weather would be clear enough to permit bombers to take off and to assemble in formation, and the afternoon weather clear enough to permit them to return and land.

It also required a day when over the Continent (Europe) the bombers could fly clear of clouds at 18,000 feet or higher, because at lower levels the German flak would be murderous and attempting to fly in formation while in the clouds and “blind” would be even more murderous. Also, the weather over the target should be clear enough to see the target for good bombing results. If the weather over the target would be cloud-covered, we would drop bombs by radar bombing, but this was not accurate.

Also, we would only drop bombs by radar if over Germany, but not over France or Belgium. If we did not drop the bombs we would bring them back to the base. This was not a good mission because we knew we would go back to this target later and the permanent personnel on the ground would have to unload the bombs, which was a dangerous and very difficult job, and they also hated to see us bring the bombs back to the base. We were told the bomb removal crew knew if the bombs had not been dropped because all planes made a very smooth and soft landing or, as the pilots would say, “greased it in” to prevent a rough landing and possibly jarring the bombs loose while landing.

As an example of the times we [458th Bomb Group] were briefed for a mission and did not go, the group reported that in March, 1944, we had 23 mission briefings but flew only 15 combat missions. Even today weather predictions, with all the new scientific data, are far from accurate, so it is not unusual that predicting weather in 1944 was a far more difficult process, but I thought the weather people over-all did a great job. While flying at high altitudes, it gets very cold. 20 degrees Fahrenheit below zero was not uncommon.

In fact, after a debriefing session, which the whole crew did after each mission, the interrogating officer asked the engineer what the temperature was and Brown said very disgustedly “I don’t know”. The officer said “Sgt., I know you had a rough mission but you know the temperature” and Brown replied “No, I don’t know because the damn thermometer only goes to 20 below”.

The B-24 had no heaters and was not pressurized and no insulation. In the back where the waist gunners were [Al Walczak pictured], they were standing by an open window and at 20 below and lower and traveling about 170 mph it was terribly, terribly cold and many men got severe frost bite and lost toes and feet and fingers because of the frost bite. When we started flying missions, we had heavy wool-lined leather jackets, pants and boots, but after about 15 missions we got electrically heated suits which were a tremendous improvement. They were much less bulky but the suits did occasionally short out and cause a burning sensation and had to be turned off at least intermittently.

This happened to me on one of our missions. I got a very strong stinging sensation on my right hip and I told Doyle to disconnect the electric suit for a short time and then plug it in. But because it had over-heated and I was sweating in that area, we got condensation on my part of the windshield. Doyle was frantically trying to keep the windshield clear and AI, the co-pilot, would fly the plane and try to stay information, which he did. Over the target and bomb run I turned the suit off entirely and we got through the mission with much discomfort. At later reunions Doyle recounted that incident and thought this was very funny, between my jumping around in my seat and yelling at him to connect and disconnect the suit. Obviously I got a new electric suit and had no other problems.

At about 10,000 feet we would put on our oxygen masks. The oxygen for each crew member was on a regulator. At 20,000 feet without oxygen, you would lose consciousness after about three to five minutes. There is no sensation of lack of air, or feeling of gagging, but only a loss of consciousness. I would therefore check the crew about every five minutes on a mission. Crew members had a number. Mine was 1, AI’s was 2, Testa was 3, etc. I would say on the intercom “Oxygen check, 1 and 2 o.k.” and then each member was to say “3 o.k.”, “4 o.k.”, etc. If one crew member did not answer right away, the next one would answer and the one not answering in sequence did so at the end of the check.

On one of these checks, Joe Brown did not answer in sequence or at the end. So I called him by name and he still didn’t answer. Joe was in the top turret which is over the flight deck right behind and above the pilot. When he didn’t answer I told Doyle, the radio operator, to check on Joe. Doyle found that somehow the oxygen hose had become disconnected and so Doyle immediately plugged it in and turned the regulator to pure oxygen. Joe immediately revived. Doyle got Joe out of turret and in a very short time Joe felt fine and went back into the turret.

Joe had no ill effects but the incident convinced the crew members of the importance of the oxygen check, because Joe could have died without it or could have suffered severe brain damage if he was without oxygen over a much longer period of time. [Bernie Doyle and Joe Brown pictured at left]

Historically, the Berlin 1000-plane raids on March 6 and March 8, 1944, were very important psychologically because it proved to Hitler and the German people that the 8th Air Force could bomb anyplace in Germany in daylight and in great numbers. These first Berlin raids were more hazardous than later missions because we did not have fighter escorts to fight the Luftwaffe planes because the range of our fighters – P-47s and P-51s – did not have the necessary full capacity to go that far. However, later the P-51s got disposable wing tanks which made it possible to escort us on missions to Berlin or any other place in Germany. Although many missions were easier than others, two of them stand out in my mind and they are No. 15 to Hamm, Germany, and No. 25 to Villeroche, France. The 29th and 30th missions are also clear in my mind.

However, before I try to describe these missions I will describe something that happened at the end of one of our briefing sessions. When the pilots are briefed, they showed how the various planes would fit into the formation. Each plane is listed by the name of the pilot. The diagram showed each 12 plane-group and the names of the pilots leading each of the three planes in this 12-plane group were: Hoffmann, Schwartz, Schulze and Vogel. Just as we were being dismissed, one of the pilots said “Wait a minute, fellows. Do you see those names? Hoffmann, Schwartz, Schulze and Vogel. Are you sure we are in the right Luftwaffe?” At least it was good for a laugh. If we were shot down, the crew was ordered to disperse and not stay together because of security reasons. However, our guys said that since I spoke German, they would stay with me regardless of that because they wanted to know what the Germans were talking about.

Our 15th mission was to Hamm, Germany, on April 22, 1944 [2BD photo at right]. Because of what happened over Hamm, Germany, and afterwards, it still leaves an indelible mark on my memory. At the early morning briefing we were told the mission was scrubbed (called off) because of bad weather over Europe. We were told to stand by and to re-assemble about 11 A.M. At 11 A.M. we were told to just stand by for a possible mission later in the afternoon.

Probably about 3P.M. we were briefed for a mission to Hamm, Germany. Hamm was a huge marshaling yard and is located in the Ruhr Valley. We were told we could expect very heavy flak, and this turned out to be a gross understatement.

As we made a left turn on to our bomb run, I saw the greatest concentration of flak I had ever seen. The sky was almost black from flak in the area of the target and before and after the target, and we were flying through it. One plane from our Group in our formation was shot down near the target. A surviving crew member of that plane wrote this about the flak. “I noticed the flak barrage boxing us in. The first box was low but dead ahead. The second was high, but still dead ahead. The third boxed the aircraft at 8 o’clock, 11 o’clock, 2 o’clock and 4 o’clock”. (Straight ahead is 12 o’clock –3 is to the right, 6 to the rear and 9 to the left).

The phrase “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death” part Verse 4 Psalm 23 (KJV) flashed through my mind. By changing the word “walk” to “fly” it seemed very appropriate at the time. I felt that on that day the Ruhr Valley was the “valley of the shadow of death”. Actually we received little flak damage to “Rough Riders” and after leaving the target at about 7:40 P.M. (1940 hours) we proceeded back to England.

Everything seemed routine since we had excellent fighter escort until shortly before we hit the English coast. It was starting to get dark and after letting down to about 4000 feet we turned on our outside lights on the wings and tail section. The formation had loosened up for the routine landing procedure.

However, at about the time we crossed to English coast, the control tower operator at our base broke in on the radio and warned us not to land because there were enemy fighters over England and that all airport landing lights were off and a landing approach would be extremely hazardous and an easy target for the enemy fighter planes. It was now completely dark and within a minute or two we received orders to fly north (360 degrees) for 20 minutes and then return to the base. We were also told to turn off all outside lights and inside lights, which left only the small fluorescent lights illuminating the instrument panel. By “we” I mean about 200 B-24s flying in absolute darkness and unable to see any other plane or them us. Everybody was also told to hold their same altitude.

After flying 20 minutes north, we were told to make a left 180-degree turn to return near our home base. Every pilot must have obeyed these instructions because there were no mid-air collisions. When we got back to the base, two of our planes were not accounted for, in addition to the one shot down over Hamm. This was a nerve-racking experience for all the crew, because we did not know if we would be attacked by fighters or have a mid-air collision. To further complicate things, the British and base anti- aircraft gunners started shooting at the enemy fighters but because there were hundreds of bombers in the air, the real damage they did, if any, was to the bombers. The German fighters were Ju-88s and Me-410s. I do not know how many but only one plane was lost by the Germans. In our Group the report shows “Two of our ships, #667 and #718, both from the 752nd Squadron, went down –667 in flames, 718 made a forced landing on the field. Nine crewmen were killed, five wounded”. It is reported that in all 13 B-24s crashed or crash landed in England and two more were damaged on the ground, 38 men were killed and 23 wounded or injured.

We landed about 10:30 P.M. and went in for de-briefing which took quite a while and we were all concerned about the two planes that had not landed. After de-briefing we went to the mess hall to eat and it was after mid-night when we finished and all of us were very tired. After most of us had finished eating, a sergeant who was with special services came in and asked if any of us wanted to see a movie. The first reaction by most of us was that this was about the last thing we needed at that time. However, the sergeant mentioned that it was not a war movie and that it was considered a real good show, and if even as many as one of us wanted to see it, he would be willing to run it for us. About 6 of us decided that we probably could not get to sleep anyway, mainly because of the concern over the two crews that had not checked in, and therefore decided to watch the movie. The name of the movie was “Going My Way” and the stars were Bing Crosby and Barry Fitzgerald, and the story involved an Irish priest trying to raise some money for some parish purposes and Bing Crosby was helping him. Crosby sang the title song and the other songs. I guess what struck me about the picture so much was that it seemed a million miles away from the war, and probably did more to relax me and the other fellows than anything that could have occurred.

The wreckage of Lt Stilson’s aircraft of the 754th Squadron

There were no other late night returns from missions where German fighters followed the planes back to England. We did have a late landing on our 29th mission which I will explain later. In a very detailed account of the Hamm mission on 22 April, 1944, in his book Night of the Intruders, Ian McLachlan writes in his Introduction: “Mission 311, on 22 April, 1944, went badly wrong. With invasion of Europe threatened, the Allies launched an audacious assault on Germany’s largest marshalling yard, at Hamm, nerve-center of the Reich’s railway system. Any raid would face fierce opposition from enemy fighters and flak. But this one was even more dangerous. Because of adverse weather reports, the American airmen, usually deployed as daytime bombers, did not depart for Hamm until late afternoon. The 824 B-17s and B-24s –with more than 8000 aircrew –had to contend with the additional hazards of darkness. Nearly 1,000 American and British fighters accompanied the bombers, but they could do little to alleviate risks such as disorientation, mid-air collisions, getting lost, or being savaged by night fighters. The fighting over Europe was ferocious. Then, as the survivors limped home, Luftwaffe intruders mingled with them, under cover of darkness. The battle-worn Americans were attacked by the enemy as they sought the sanctuary of their own airfields –and in the resulting carnage and confusion, Allied coastal and airfield defenses were firing on friend and foe alike. Agonized, local inhabitants could only look on as aircraft, consumed in flames, seared across the night sky to destruction on farmland and marshes. Others, too low for baling out and too damaged to climb, struggled to land before fire severed vital controls or detonated ruptured fuel tanks. That night the Americans suffered their highest ever losses to German intruders. I hope that this book, which tells the full story for the first time, will serve as a memorial to the men who died, and a tribute to the courage of all those involved.

“Colonel James H. Isbell (now Brigadier General-retired) replied to the said author’s questions that records were hard to verify.’ The fact that you found no explanation in the Archives is indicative of the faint importance we attached to historians and history. Hell! We had a war to win’. However, he later conceded ‘I wish we had done a better job of recording the facts.’

Rough Riders, lower left at bomb release point

I asked the navigator, Scorza, how far it was to Switzerland. Switzerland was a neutral country and they permitted planes to land there, but they would not release you or the plane for the duration of the war. The navigator, Sam Scorza, informed me we were closer to England than to Switzerland. Some of the crew still thinks Sam had a date in England and therefore suggested England. But in defense of Sam, I recently checked the mileage and it was closer to the southern part of England.

Not too far from the White Cliffs of Dover there was an emergency field called Manston which had a runway 9000 feet long and 750 feet wide, with a heavily grassed area at both ends of the runway. This was the field we were hoping to make. As soon as we could, we released the bombs over open fields and since we did not remove the pins from the bombs I do not think any bombs exploded on impact. Since we were over France we did not want to do any damage but we had to get rid of the weight of the bombs which was at least 4000 lbs. Also since this was before “D-Day”, France was enemy territory and bailing out would have meant almost certain capture by the Germans.

We had no fighter escort and we were about 200 miles from Manston and very vulnerable to attack by the German planes but none of this happened. I have always felt that our guardian angel was with us on that flight. I was hoping to hit the English Channel at 10,000 feet, and did.

As we neared the channel, No.4 engine began to run very rough. As we were letting down to about 7000 feet, No.3 engine, the one that had quit first, started to windmill and with some effort it started to fire very unevenly and about this time No.4 engine stopped and we feathered it. The B-24 flies fairly well on two engines and I knew that on one engine the B-24 will fly, but it will lose 200 feet a minute with using 20 degrees of wing flaps. (I had practiced this at least twice by simulating it in practice and reading about it in the B-24 manual.) As soon as we were over the channel a fighter plane came up to escort us to Manston. At this time I ordered the crew to throw out everything that was loose, which included flak vests, all ammunition and .50 caliber guns which could be dismantled. No.3 engine continued to run roughly and was putting out about 50% of normal power. No.1 engine was running smoothly.

Making a long approach to the runway, we lowered the landing gear, and since No.3 engine controls the hydraulic system, the wheels did drop and locked into place, although the wheels could have been lowered manually in an emergency. So we landed with No.1 engine at full power and No.3 engine at 50% power. No.2 and No.4 engines were dead. After we landed and parked the plane, two of the gunners said they had to make a telephone call. At the time it didn’t make sense to me, but I said o.k., and told them to be back in 15 minutes. I found out later that they called their barracks at our home field to let the guys know they were safe in England so that they would not divide up their personal belongings, assuming we had been shot down over Europe. All combat crew members made this arrangement with their friends in the event they didn’t come back from a mission.

Rough Riders stayed at Manston and I never saw it again. I left England late in July 1944 and it had not returned to Horsham St. Faith at that time. Operations did tell me that according to their information from Manston, that only No.3 engine could be started. Remember No.3 was the engine that stopped first and then partially ran again when we got down to about 7000 feet. They believed that No.3 stopped at 20,000 feet because the booster fuel pump failed at the high altitude but the regular fuel pump was o.k. below 10,000 feet. Many years later, I found out that a reconditioned B-24 with the same serial number as Rough Riders was returned to Horsham St. Faith, but completely reconditioned, and whether it was still called Rough Riders I do not know, but this plane was shot down on 9 September 1944 over Trier, Germany. The squadron records show “ship #342-S 755th Sq. lost, believed seen going down very fast with a smoking engine just north of Trier, Germany”. The numbers “342” were the last three numbers of Rough Riders; “S” the squadron letter, and 755th was our squadron.

During this 25th mission every crew member performed to perfection for which I was then and still am very proud and thankful. Incidentally, Sam Scorza did have a date that night and we all got back to Horsham St. Faith that same night.

In 1983 Jean and I went on a European tour, through Switzerland, with Joe and Louise Brown and Bernie and Corrie Doyle, and while we were going by bus through a beautiful valley with high mountains on each side, we noticed what looked like a long runway down the center of the valley. Joe Brown and Bernie Doyle asked me if we might have landed on that runway on our 25th mission if we had gone to Switzerland. I told him there were two approved landing strips but I did not remember where they were. Just as we were talking, the side of the mountain opened up like huge hangar doors and three fighter jet airplanes rolled out of the cavern in the mountain, and rolled out on the runway and took off information. In a short time the planes were gone and the huge mountain side doors closed and the valley again became a quiet peaceful place. To us it was right out of a suspenseful spy movie. We found out later that Switzerland utilizes the mountains not only for planes and repair depots, but for hospitals, emergency food supply, government office areas, etc. in the event someone would dare to violate their neutral position in a war-torn Europe. Although they have been neutral during many of the wars, they have universal mandatory military training. Driving through the country, the average tourist would not be aware of this, because all we saw was a quiet peaceful and beautiful country, with hardworking people, proud of their lifestyle and their country.