458th Bombardment Group (H)

Ice and Fire

Two War Stories

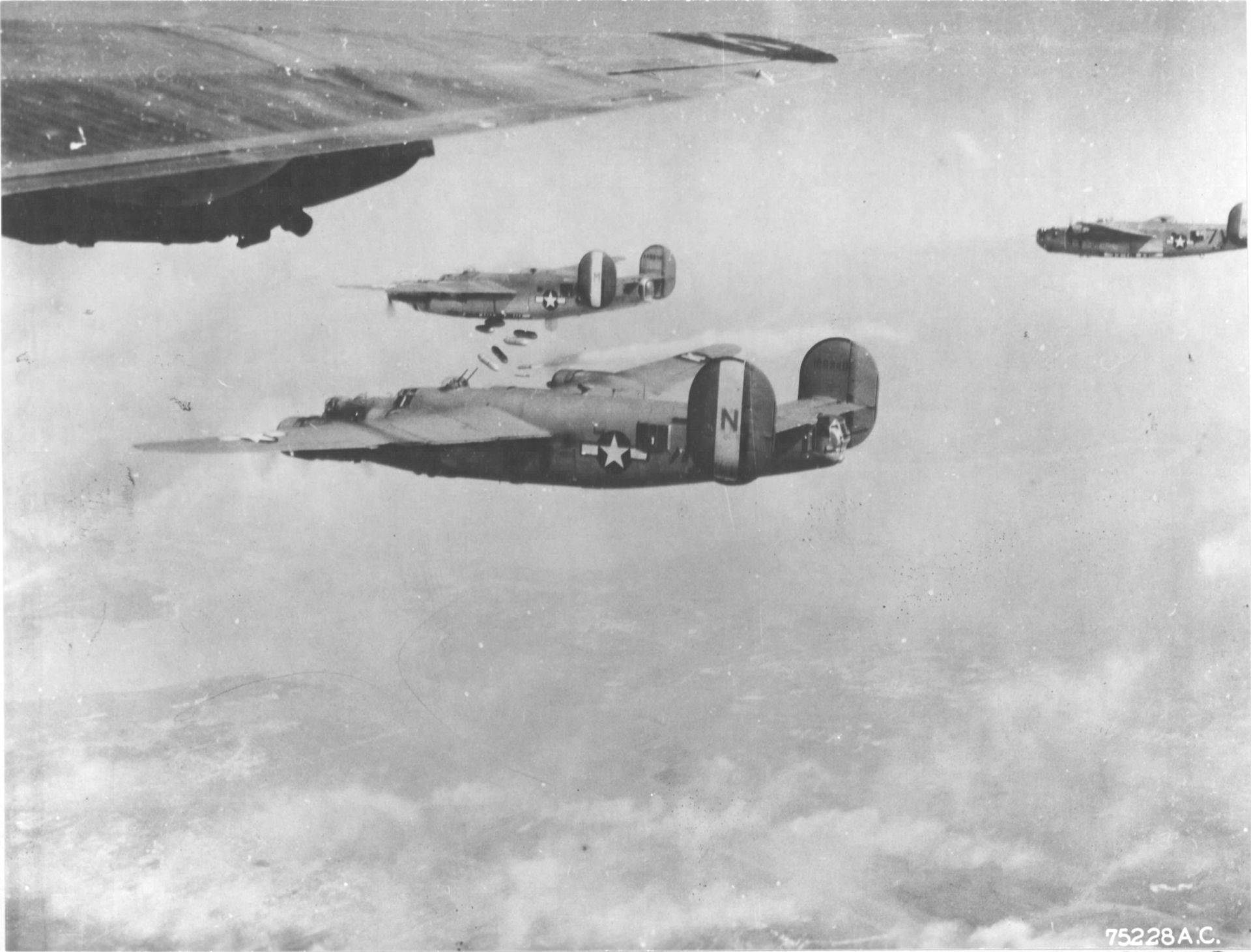

May 1944: B-24H-15-CF 41-29340 7V N Yankee Buzz Bomb shown before the removal of its olive drab paint.

These two stories were submitted by the pilot of the Holmgren Crew in the 752nd Squadron

Ice

The B-24 Liberator was a powerful war machine, capable of non-stop transport of up to five tons of explosives for distances of 1,000 miles and the return to base. The Liberator had a crew of ten men-each trained for a specific task. We were part of the U. S. Eighth Air Force based in England, and assigned to the 458th Bomb Group (H) at a former RAF base near Norwich in East Anglia. We arrived in Southampton in January 1945 after a 10 day Atlantic convoy passage from New York and soon thereafter found ourselves assigned to the 752 Sq. of the 458th BG at Horsham St. Faith.

By April 1945 it was becoming clear that the war in Europe was winding down. However, the Allied experience at Bastogne in December 1944 through January 1945, when Hitler unleashed a fierce counter-offensive culminating in the Battle of the Bulge, taught the Allies the folly of predicting victory before its arrival. The crew of 340N (Nan) had flown missions in fifteen out of sixteen days during February 1945. Why so little relief between missions? To an air crew it was an indication that the brass had concluded that the war was about to end and therefore it was no longer necessary to dispatch replacement crews to fill the ranks of those completing their tour of duty or otherwise out of action. We had flown almost as much in March, but had some respite due to bad weather that kept us from flying almost daily. At this stage of the air war over Europe targets were primarily transportation and oil, i.e., railway marshalling yards and oil refining and storage facilities. The Wehrmacht required huge supplies brought by rail—and to cut off such delivery was the task of the Eighth Air Force.

It was 0400 on April 5, 1945 when the wake-up orderly pounded on my door and barked, “Sir, mission briefing at 0545”. Co-Pilot Herman Bull and I tumbled from our bunks and dressed in dark silence. As we made our way to the officer’s mess we went through the ritual routine of speculating on the day’s target. It was cold and a heavy overcast added a somber pall to the pre-dawn darkness.

“Maybe it’ll be scrubbed,” hopefully murmured Paul Gable, the navigator. We quickly and silently ate our mission breakfast which consisted of fresh fruit, fresh scrambled eggs, fresh whole milk, toast and coffee. The breakfast fare for crews not flying a combat mission that day would be canned fruit, powdered milk, powdered eggs and spam—all tasteless and ersatz.

The mission breakfast was served only to those going into mortal combat in the spirit of the condemned eating a final hearty meal.

We arrived at Buncher 17 about forty minutes after take-off, flying in a sky akin to a large bowl of thick creamy soup for the entire distance. We were more or less in the clear with not another airplane in sight. After flying around the area of the Buncher for what seemed like several minutes in an unsuccessful attempt to find the formation we left the immediate area of Bu. 17. Breaking radio silence (a court martial offense in anything but an emergency) I called Lincoln Red leader to learn the group’s position. Red leader replied that the group was at the designated assembly area and altitude and I should get my butt over there PRONTO!

While on the inter-com with the navigator trying to get a compass heading to get back to the assembly area I noticed that wing icing was getting thick. The wing surfaces had been icing up while we were climbing and the de-icer boots were successfully breaking it off.

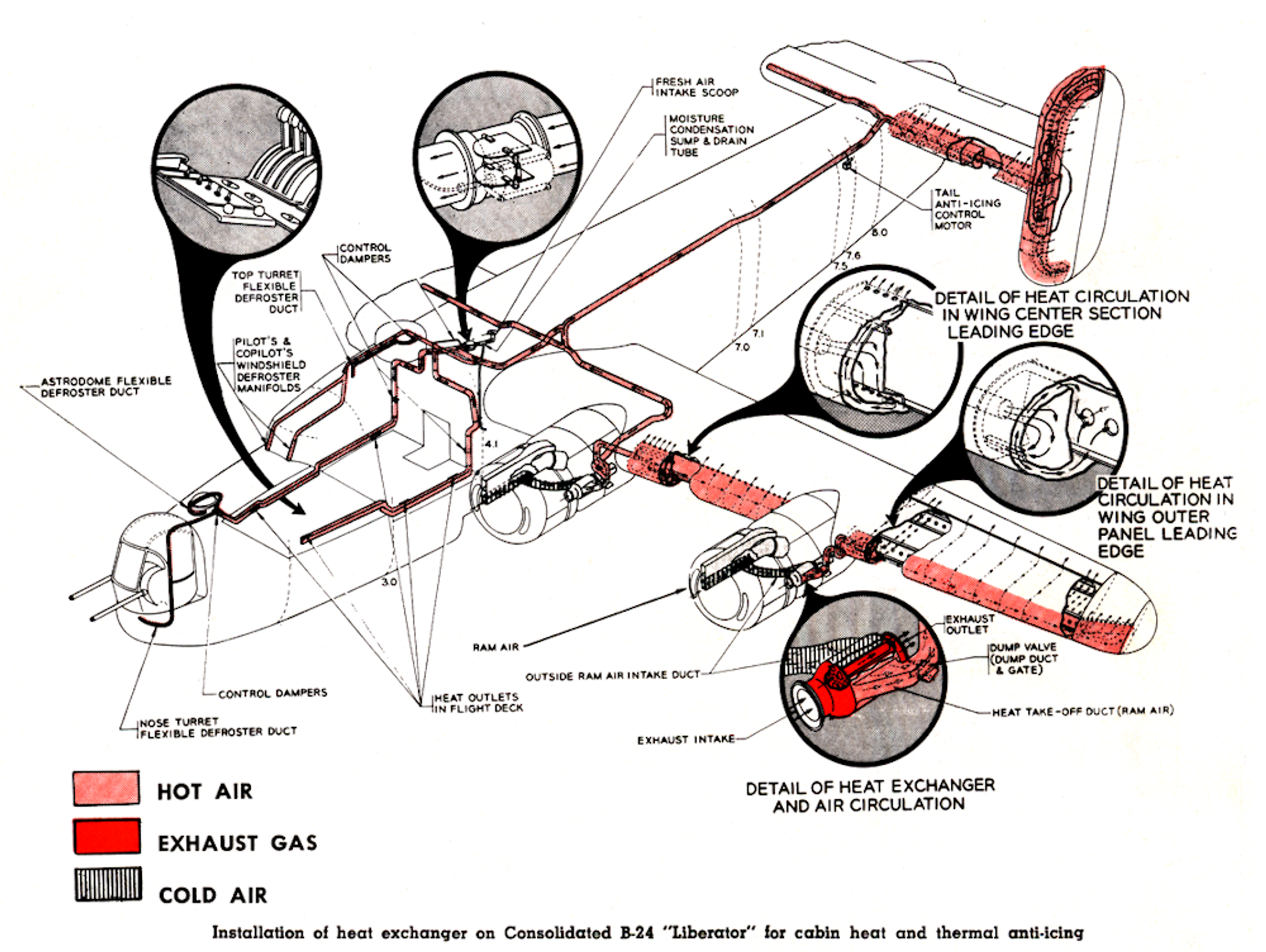

Then it happened: the airplane began to stall despite the fact that all four engines were pulling 2300 RPM and 36 inches of mercury on the turbo-super chargers, normal engine power settings for straight and level flight. The only apparent danger seemed to be the excessive icing on the leading edges of the wing and tail surfaces – icing that would not respond to successive inflation and deflation of the hydraulic de-icing system [click image above]. Shorty Richardson, the tail-gunner reported that the elevator surfaces were quickly icing and there was no apparent action of the tails de-icing boots.

In an attempt to break the stall and regain air speed I thrust the nose of the airplane down. As the airplane regained air speed I could not pull the wheel back to straight and level flight. I shouted to Herman to get on his wheel so we could pull back together – he did and no such luck. The airplane entered a gentle spin, lost altitude and gained airspeed, accelerating to 320 mph (normal straight and level air speed was 180 mph). Realizing that I had little control of the airplane and no certainty that control would return, I ordered the crew to make preparations to bail out. As conditions rapidly worsened I hit the Klaxon horn, signaling the order to bail out.

The flight engineer Joe Metosh, the radio operator Rollin Helbling and Dean Burke, the nose gunner left via the catwalk at the front of the bomb bay. Shorty Richardson, the tail gunner, Ted Semchuck the ball turret/ armorer and an unknown waist gunner left through the rear catwalk of the bomb bay. As I was preparing to emerge from my seat on the flight deck to follow the co-pilot, Herman Bull to the bomb bay for our departure I noticed the nose of the airplane beginning to come up. I motioned Herman to get Gable out of the catwalk where he was preparing his departure. A mild struggle ensued between the two as Gable motioned in the windswept noise for Herman to push him out of the aircraft. (No one bails out of an airplane without a push, shove or kick). Herman finally prevailed and got Gable back onto the flight deck and we three regained our seats.

After taking stock of our situation we knew that: 1) the airplane was not going to crash onto a French or Belgian farm: 2) the crew was short handed by two thirds and 3) we were certainly in no position to complete the mission to Hof. We were still flying on instruments at about 7,000 feet the wing and tail icing was gone; thus the reason for the airplane’s ability to assume straight and level flight, the temperature was warmer. I eased down to an altitude slightly below 4,000 feet and finally left the cloud cover.

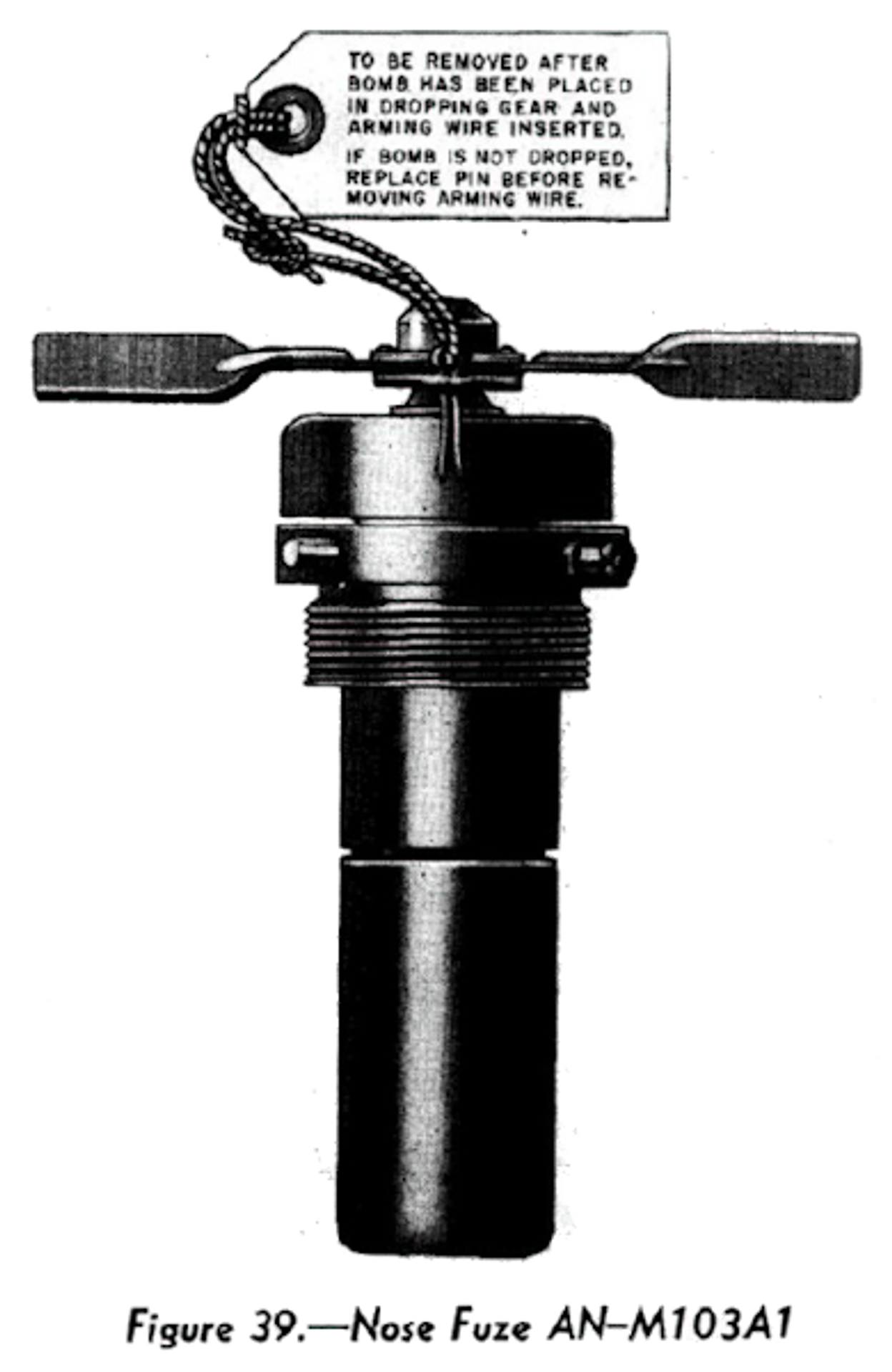

Not knowing where in the geography of France or Belgium we were I radioed NUTHOUSE, an emergency radio station of the continent and explained our plight. NUTHOUSE replied with a compass heading and instructions to fly for ten minutes to a nearby air base for landing. It was then that I remembered that the bomb load we carried was armed and the safety pins, which are kept on each bomb until after takeoff, were removed. Ted Semchuck, the armorer, had carefully put them into the pocket of his flight jacket. And where was Ted Semchuck and the pocketful of safety pins at that moment? I was not certain, but we knew it would not be prudent to land an airplane with a full load of armed and ready bombs and a lot of gasoline onto an airfield with a short runway. Once again I called NUTHOUSE and described the situation regarding the armed and painless bomb load. The response was swift and unambiguous. “Stay the f- – – outta here!” Upon regaining his composure the radio operator instructed me to fly to the Channel and dump the bombs in the 50 square mile area in the Channel which was closed to all surface shipping. This was the spot where returning airplanes with bombs that failed to release at the target area were jettisoned.

We dropped down to about 2,000 feet and flew over the beautiful French Countryside. The small fields appeared April green as we flew on a course to the Channel and a bomb-free airplane. Before arriving at the Channel the airspeed indicator became inoperative. Not to worry – the Navigator’s instrument was OK and he periodically gave me the reading over the inter-com. After reaching the Channel we lost contact with NUTHOUSE and switched over to COLGATE, an air-sea rescue station on the English coast. In the meanwhile Gable was working the GEE box, an early form of radar navigation in an effort to electronically guide us to the bomb disposal area. COLGATE provided a compass heading and time to reach the disposal area. After several minutes COLGATE says it is OK to jettison the bombs. Gable, who has been fiddling with the knobs on the GEE box shrieks over the intercom, “NO, NO WE’RE OVER LONDON!” Once again I called COLGATE and was reassured that we could safely drop the load. I lift the bomb release lever and Herman looks over his shoulder to see that all ten bombs have, with certainty, left the airplane.

We then head for home to await word on the fate of the new members of the Caterpillar Club (anyone who has made an emergency parachute jump). Upon landing we are debriefed and learn that the entire mission was fouled up by the execrable weather. Like us, other crews of the group were unable to find their formation and flew with others. Some were short of fuel and landed in France and some were already back at the base, having given up in frustration. For us three who made it back it had been four hours since we took off at 0700. And now it was time to sweat out word of the fate of the rest of the crew.

By the end of that evening we learned that Metosh, Burke and Helbling were back at base. They had landed safely in Belgium and were picked up by an American artillery group that had seen them bail out. They were taken by Jeep to a nearby airbase where one of the airplanes from our group had landed for refueling and returned home with the three passengers. The other crew members had a scary but ultimately satisfactory outcome. The tail gunner, Richardson, landed in a Belgian school yard as a horde of school children rushed out to greet him, including a pistol-wielding schoolmaster who held the weapon to Richardson’s head. Apparently the town had been strafed moments before and the schoolmaster thought that Shorty might be a Luftwaffe pilot. Richardson was able to convince him of his nationality, aided by a U S flag patch on his jacket and a plastic card in his pocket which explained in Dutch, French and German: “I am an American”. It probably helped that he too was spotted by an American artillery battery outfit as he drifted down, which drove into the schoolyard and rescued him from an uncertain fate. Semchuck, the man with a pocketful of safety pins, landed in a field as the farmer was engaged in Spring plowing. He was helped by the farmer and made it to the same airbase that Shorty had been transported to and he and the other waist gunner all returned to Horsham the following day.

Two days later we were flying again – in a different airplane – to Lauenberg, southeast of Hamburg and a munitions dump. On this and subsequent missions we carried a back-up supply of safety pins stored in the bomb bay. On that ill-fated fiasco we were not credited with a mission completed. Mission credit was earned only in those efforts in which a crew faced the enemy in combat. Bad weather or malfunctioning systems were not the enemy. Nevertheless, the war in Europe ended one month later and we did get to go home, having completed twelve missions.

And now fifty-five years later I look back on the thwarted mission to Hof as one of the greatest and most profound learning experiences of my life.

Copyright March 2000 Edward L Holmgren

Fire

April 15, 1945: B-24H-15-CF 41-29340 7V N Yankee Buzz Bomb (lower center) flown by Holmgren and crew.

This is the second of a series of personal accounts of the author’s World War 2 experiences, beginning with Ice: A War Story. The problem of transporting and disposing 3. 3 million pounds of Vietnam-era Napalm was prominent in recent news accounts and quickly brought to mind my own experience in the latter days of the war in Europe and my encounter with this incendiary substance called Napalm.

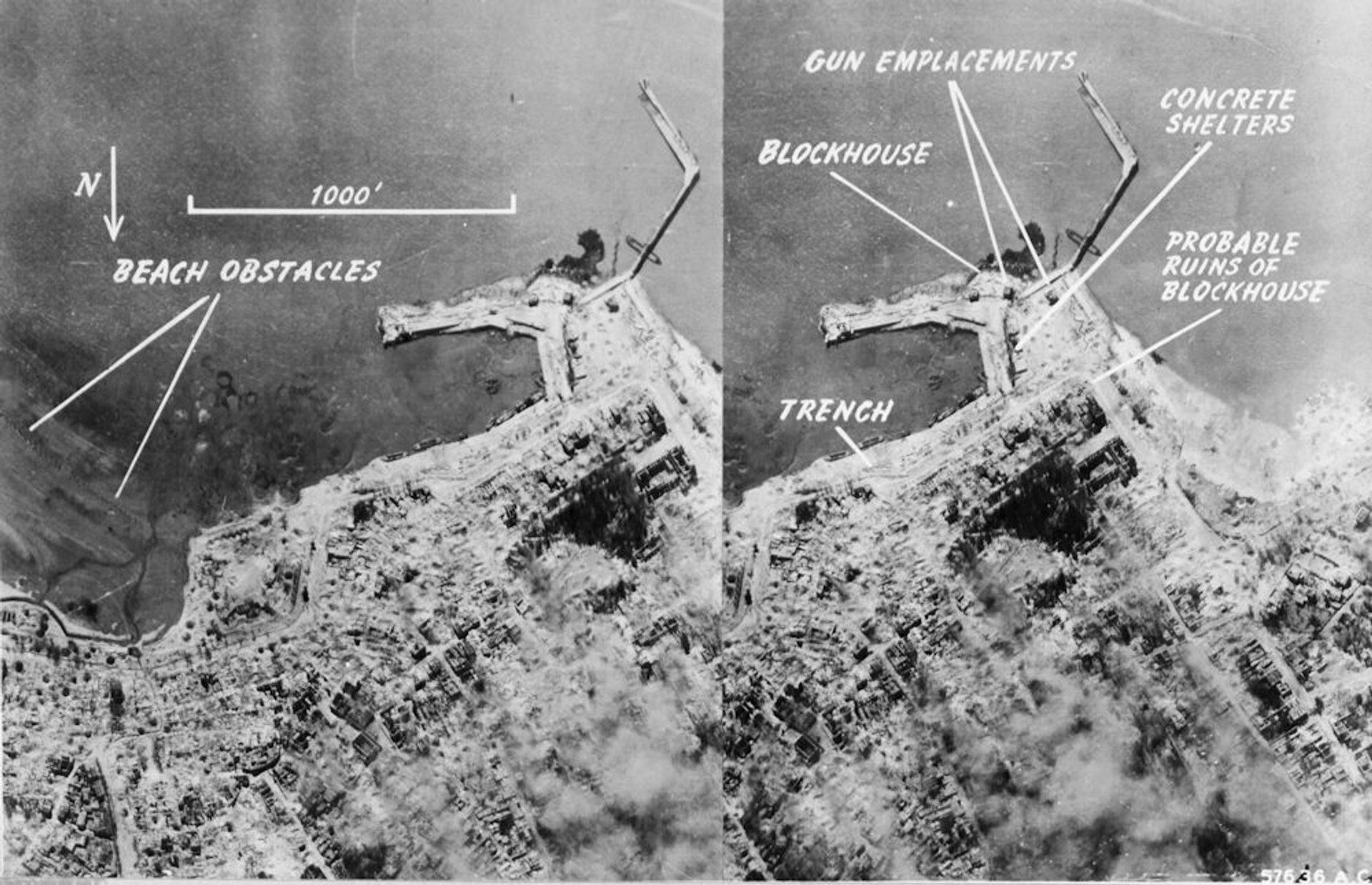

The date was 15 April 1945, a few days after the death of FDR and less than a month before VE Day. It was the first mission that the crew had flown which was of a tactical rather than a strategic nature. At the briefing that morning we were told that the target was an area of the Gironde estuary, about 50 miles north of Bordeaux. This came as a surprise to most of the crews. Wasn’t that part of France long since liberated following D-Day in June 1944? No, it was a portion of the French Atlantic coast that had been left to the Wehrmacht following the ’44 in invasion. It was said that there were some 200,000 German troops in the heavily fortified areas of Royan, Bordeaux, Pointe de Grave, and Pointe Coubre. The German force consisted primarily of anti-aircraft gun batteries that the French ground forces had been unable to dislodge.

The briefing officer then told us that our bomb load would consist of Napalm, carried in fighter plane wing-tip drop tanks and that this was to be the first time that Napalm was being used as a bomb. The tanks were filled with 500 pounds of jellied gasoline (Napalm) and a hand grenade placed inside was meant to explode on impact would detonate each tank. We all looked at each other, mouths agape. “Wasn’t napalm the weapon that the troops in the Pacific used in flame throwers to dislodge Japanese from caves and such?” The reply was, “Yes.” We would be loaded with eight of the Napalm filled tanks, weighing 500 pounds each – four tons of fire on each aircraft. Another reason that such a large force of airplanes could be spared for this action was the fact that we had just about run out of targets over the German homeland.

We had a pre-dawn take off and assembled the formation over the Continent at Liege and thence south toward the target. We flew at 15,000 feet, lower than most missions because we did not expect heavy flak. The French countryside was especially beautiful in that spring of 1945 and the crew, not having to keep a watchful eye peeled for enemy aircraft, enjoyed the site of multi-colored fields and their expressions of spring green color and new growth. However, I wasn’t so fortunate. About an hour into the flight, Metosh, the flight engineer reported that several of the tanks appeared to be leaking gasoline. There already had been a no “smoking order” issued for this operation because of the known volatility of the Napalm, but leakage was another matter. The odor of gasoline was unmistakable and heavy. I ordered the bomb bay doors opened in an effort to avoid a spark or some other mishap that might cause an explosion. Other airplanes were signaling their intention to abort the mission because of excessive leakage and return to base via the famous “50 square mile Channel dumping area”. The wing-tip tanks were made of heavy paper mache and apparently the colder temperatures at altitude, or whatever, rendered them porous and thus the oozing of this smelly liquid had transformed what had started out as a milk run into the gorgeous French country into a flight to hell. And we weren’t even half way to the target!

We soldiered on with the remainder of the Group to the target area. As we drew closer to the target I looked out my windshield and viewed what was the most complete blanket of flak that I had ever seen. It virtually covered the sky through which the airplanes were flying. And moments later we were buffeted about by the concussive explosion of the shells all around us. Oh, God, please don’t let one of those shells hit the bomb bay and have us go up in a hail of fire and broken metal. And God answered by preventing us safe passage as the flak eased; those guys ahead of us must have gotten to those guns.

We continued on to the Group’s assigned target, which was a barracks and building area. It couldn’t be determined whether we had hit it because a tower of thick, black smoke from the bombs dropped by preceding wings formed a pall over the target area. By the time we had made the 180 degree turn for home the smoke had risen to our flight level at 15,000 feet.

We flew home over the Bay of Biscay and onto the south coast of England at Southampton and arrived at base 8 hours and 40 minutes after takeoff. This was the first and only use of napalm in the European air war and the results were deemed “ballistics poor”. A few months later general Curtis LeMay and the 20th Air Force flying the Super Fortress used Napalm extensively in the enormous firestorm raids on Tokyo, the prelude to the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bomb attacks.

Eight hundred and sixteen B-17s and B -24s took off from bases in England and seven hundred and eighty three were effective, i.e., they made it to the target and dropped their loads. The other 33 aborted for reasons including mechanical problems, leaking Napalm tanks, etc. The effective bomb load totaled 1556 tons of jellied gasoline, Napalm raining flame and destruction on the Gironde estuary, an amount that is almost equal to the total weight of Napalm transported from California to northern Indiana and back.

May 6, 1998 Ed Holmgren

Photos: FOLD3