458th Bombardment Group (H)

Bachelor’s Bedlam

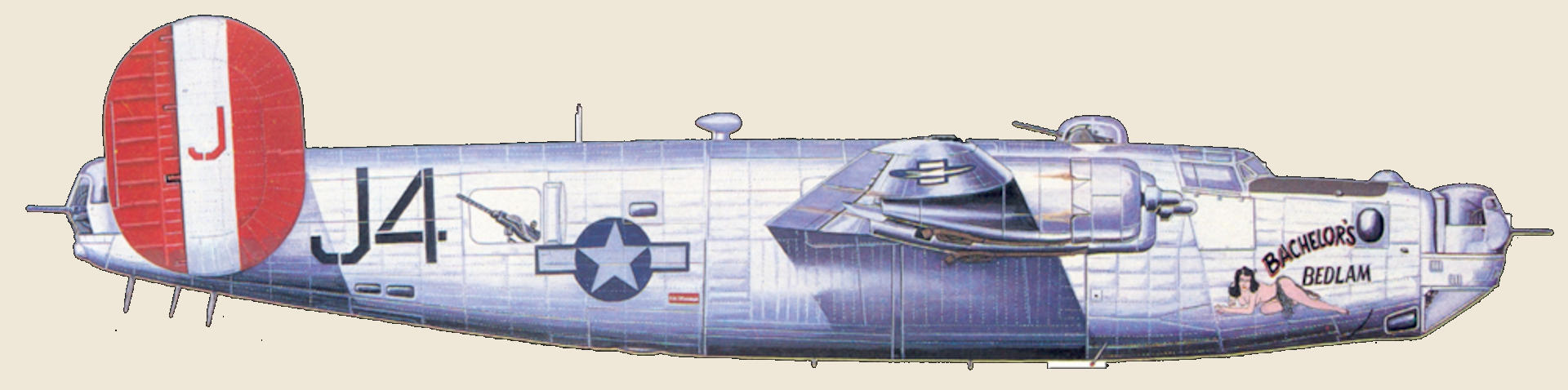

B-24JAZ-155-CO 44-40287 J4 J

Bachelor’s Bedlam on a Horsham hardstand

Unknown – Possibly RTZ in June 1945

Bachelor’s Bedlam was an original AZON ship, arriving at Horsham St. Faith in May 1944. On only it’s second AZON mission, the Nose Turret Gunner on the AZON crew of 1Lt Patrick McCormick was killed by flak. The aircraft completed 68 combat missions, flying its last on April 25, 1945.

Missions

| Date | Target | Pilot | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 08-Jun-44 | UNSPECIFIED TARGETS | McCORMICK | AZ04 | -- | J | J4 | -- | ABANDONED - WEATHER |

| 14-Jun-44 | 5 TARGETS | McCORMICK | AZ06 | 1 | J | J4 | 1 | |

| 15-Jun-44 | 3 RAILWAY BRIDGES | McCORMICK | AZ07 | 2 | J | J4 | 2 | SGT TOMLINSON KIA - FLAK |

| 20-Jul-44 | EISENACH | McCORMICK | 95 | 7 | J | J4 | 3 | |

| 21-Jul-44 | MUNICH | CANADY | 96 | 2 | J | J4 | 4 | |

| 24-Jul-44 | ST. LO AREA | McCORMICK | 97 | 8 | J | J4 | 5 | |

| 25-Jul-44 | ST. LO AREA "B" | McCORMICK | 98 | 9 | J | J4 | 6 | |

| 31-Jul-44 | LUDWIGSHAFEN | McCORMICK | 99 | 10 | J | J4 | 7 | |

| 01-Aug-44 | T.O.s FRANCE | KRAMER | 100 | 1 | J | J4 | 8 | |

| 02-Aug-44 | 3 NO BALLS | McCORMICK | 101 | 11 | J | J4 | 9 | |

| 05-Aug-44 | BRUNSWICK/WAGGUM | COOK | 105 | 9 | J | J4 | 10 | COMPOSITE w/466 |

| 06-Aug-44 | HAMBURG | McCORMICK | 106 | 12 | J | J4 | 11 | |

| 18-Aug-44 | WOIPPY | HEALY | 116 | 1 | J | J4 | 12 | |

| 25-Aug-44 | TERTRE | BOWERS | 119 | 1 | J | J4 | 13 | |

| 09-Sep-44 | MAINZ | COOK | 124 | 20 | J | J4 | 14 | |

| 11-Sep-44 | MAGDEBURG | DAVIDSON | 126 | 29 | J | J4 | 15 | |

| 03-Oct-44 | GAGGENAU | FIELDS | 127 | 2 | J | J4 | 16 | |

| 09-Oct-44 | KOBLENZ | STOESSER | 131 | ABT | B | J4 | -- | ABORT - #1 ENG OIL PRES |

| 17-Oct-44 | COLOGNE | FIELDS | 135 | 5 | J | J4 | 17 | |

| 19-Oct-44 | MAINZ | TRACY | 136 | 24 | J | J4 | 18 | |

| 22-Oct-44 | HAMM | FIELDS | 137 | 6 | J | J4 | 19 | |

| 26-Oct-44 | MINDEN | FIELDS | 138 | 7 | J | J4 | 20 | |

| 04-Nov-44 | MISBURG | FIELDS | 141 | 8 | J | J4 | 21 | |

| 06-Nov-44 | MINDEN | FIELDS | 143 | 9 | J | J4 | 22 | |

| 08-Nov-44 | RHEINE | GLAGOLA | 144 | 28 | J | J4 | 23 | |

| 09-Nov-44 | METZ AREA | FIELDS | 145 | ABT | J | J4 | -- | ABORT - LAND OFF LOCATION |

| 25-Nov-44 | BINGEN | EIDELSBERG | 149 | 6 | J | J4 | 24 | |

| 26-Nov-44 | BIELEFELD | FIELDS | 150 | 12 | J | J4 | 25 | |

| 11-Dec-44 | HANAU | FIELDS | 155 | 13 | J | J4 | 26 | |

| 12-Dec-44 | HANAU | McCORMICK | 156 | 15 | J | J4 | 27 | |

| 24-Dec-44 | SCHONECKEN | FIELDS | 157 | 14 | J | J4 | 28 | |

| 30-Dec-44 | NEUWIED | McCORMICK | 161 | 17 | J | J4 | 29 | |

| 31-Dec-44 | KOBLENZ | McCORMICK | 162 | 18 | J | J4 | 30 | |

| 03-Jan-45 | NEUNKIRCHEN | McCORMICK | 165 | 19 | J | J4 | 31 | |

| 07-Jan-45 | RASTATT | McCORMICK | 166 | 20 | J | J4 | 32 | |

| 08-Jan-45 | STADTKYLL | SHANNON | 167 | 5 | J | J4 | 33 | LAND OFF LOCATION |

| 28-Jan-45 | DORTMUND | McCORMICK | 174 | 22 | J | J4 | 34 | |

| 03-Feb-45 | MAGDEBURG | KELLY | 177 | 2 | J | J4 | 35 | |

| 06-Feb-45 | MAGDEBURG | BECKSTROM | 178 | 21 | J | J4 | 36 | |

| 08-Feb-45 | RHEINE M/Y | McCORMICK | REC | -- | J | J4 | -- | RECALL - WEATHER |

| 09-Feb-45 | MAGDEBURG | McCORMICK | 179 | 24 | J | J4 | 37 | |

| 15-Feb-45 | MAGDEBURG | WILLIAMS, DG | 182 | 11 | J | J4 | 38 | |

| 17-Feb-45 | ASCHAFFENBURG M/Y | McCORMICK | REC | -- | J | J4 | -- | RECALL - WEATHER |

| 19-Feb-45 | MESCHADE | McCORMICK | 184 | 27 | J | J4 | 39 | |

| 20-Feb-45 | NUREMBURG TANK FACT | KLEIN | REC | -- | J | J4 | -- | RECALL - WEATHER |

| 21-Feb-45 | NUREMBERG | McCORMICK | 185 | 28 | J | J4 | 40 | |

| 22-Feb-45 | PEINE-HILDESHEIM | BECKSTROM | 186 | 26 | J | J4 | 41 | |

| 27-Feb-45 | HALLE | McCORMICK | 191 | 30 | J | J4 | 42 | |

| 28-Feb-45 | BIELEFELD | BROWN, R | 192 | 5 | J | J4 | 43 | |

| 01-Mar-45 | INGOLSTADT | McCORMICK | 193 | 31 | J | J4 | 44 | |

| 02-Mar-45 | MAGDEBURG | McCORMICK | 194 | 32 | J | J4 | 45 | |

| 03-Mar-45 | NIENBURG | BECKSTROM | 195 | 29 | J | J4 | 46 | |

| 04-Mar-45 | STUTTGART | McCORMICK | 196 | 33 | J | J4 | 47 | |

| 05-Mar-45 | HARBURG | McCORMICK | 197 | 34 | J | J4 | 48 | |

| 08-Mar-45 | DILLENBURG | McCORMICK | 199 | 35 | J | J4 | 49 | |

| 10-Mar-45 | ARNSBURG | McCORMICK | 201 | 36 | J | J4 | 50 | |

| 12-Mar-45 | FRIEDBURG | EIDELSBERG | 202 | 23 | J | J4 | 51 | |

| 14-Mar-45 | HOLZWICKEDE | MONTGOMERY | 203 | ACC | J | J4 | -- | DAMAGED - GRND EXPLOSION |

| 19-Mar-45 | LEIPHEIM | GILBERT | 207 | 2 | J | J4 | 52 | LAND IN FRANCE (?) |

| 22-Mar-45 | KITZINGEN | KELLY | 210 | 15 | J | J4 | 53 | |

| 23-Mar-45 | OSNABRUCK | SEALY | 211 | ABT | J | J4 | -- | ABORT - ROUGH ENGINE |

| 24-Mar-45 | NORDHORN | DURIAVICH | 212 | 4 | J | J4 | 54 | |

| 25-Mar-45 | HITZACKER | EIDELSBERG | 214 | 27 | J | J4 | 55 | |

| 30-Mar-45 | WILHELMSHAVEN | DANTLER | 215 | 5 | J | J4 | 56 | |

| 31-Mar-45 | BRUNSWICK | DANTLER | 216 | 6 | J | J4 | 57 | |

| 04-Apr-45 | PERLEBERG | EIDELSBERG | 217 | 29 | J | J4 | 58 | |

| 05-Apr-45 | PLAUEN | SLOAN | 218 | 6 | J | J4 | 59 | |

| 06-Apr-45 | HALLE | EIDELSBERG | 219 | 30 | J | J4 | 60 | |

| 07-Apr-45 | KRUMMEL | SLOAN | 220 | 7 | J | J4 | 61 | |

| 08-Apr-45 | UNTERSCHLAUERSBACH | WILBURN | 221 | 24 | J | J4 | 62 | |

| 09-Apr-45 | LECHFELD | WILLIAMS, DG | 222 | 29 | J | J4 | 63 | |

| 10-Apr-45 | RECHLIN/LARZ | McCOY | 223 | 20 | J | J4 | 64 | |

| 15-Apr-45 | ROYAN AREA | HACKEY | 226 | 3 | J | J4 | 65 | |

| 18-Apr-45 | PASSAU | WILLIAMS, DG | 228 | 33 | J | J4 | 66 | |

| 20-Apr-45 | ZWIESEL | FLEMING | 229 | 2 | J | J4 | 67 | |

| 25-Apr-45 | BAD REICHENHALL | LaJEUNESSE | 230 | 30 | J | J4 | 68 |

2Lt Harry Craft [right] was the navigator of 1Lt Patrick McCormick’s AZON crew in the 753BS. He wrote this account of their second mission on June 15, 1944 in which nose gunner, Sgt. Raymond Tomlinson was killed in action and pilot Pat McCormick was wounded.

Surprise was the only element in common with our first and second missions. On June 14, 1944, we were awakened at 4:30 a.m., ate breakfast at 5:00, and position briefings began at 5:45. Take-off was set for 7:06 a.m., and the target was a bridge at Peronne in the north of France. The weather was about 50 percent cumulus clouds and 50 percent sun, ground wise, both in East Anglia and over France. Our first mission had gone off without a hitch six days earlier, two days after D-Day. The 458th Group put up three squadrons for another target on the 14th. We were one of 10 Azon crews that arrived at Horsham St. Faith the end of May, and were assigned special targets, usually elongated structures.

Our bomb run called for an altitude of 16,000 feet from our IP until one minute after drop! Azon bombs were 1,000 pounders with movable tail fins. The bombardier controlled a transmitter which sent left and right turn signals to a receiver mounted between the fins. Each plane in the formation had a different flare color streaming from its bombs, so the bombardiers could identify and “steer” their own bombs.

The crew had been selected at the end of replacement crew training in Tonopah, NV, in mid-March 1944. Skeleton crews without waist, tail, and nose gunners were flown from San Francisco to the Orlando, FL area for Azon mission training. We were instructed and practiced for six weeks in central Florida, all at altitudes of only six to seven thousand feet! We didn’t know it, but that was an acceptable “flak free” altitude for flying missions out of India, and India was our unannounced but planned overseas destination.

The four gunners with whom we’d trained at the RCU were put on a surface vessel in San Francisco Bay and sailed off for Bombay, to meet us “there” later. All of our (skeleton crew) personal gear and winter uniforms went along on that ship in footlockers!

Early in May we were flown to Hunter Field outside of Savannah, where we picked up shiny new B-24 J’s, specially equipped with Azon transmitters. Two test flights later, we were back in south Florida being briefed to fly off on a 120 degree heading, with sealed orders to open 40 minutes after take-off. The 10 crews flew separately, taking off about six minutes apart. Pilot Pat McCormick, leader of our crew, opened the orders on time. We all learned that Karachi, India was our ordered destination, via Trinidad, Belem, Natal, Ascension Island, Accra Khartoum, etc. As navigator, I was asked to supply a heading from where we were to over fly Puerto Rico, then to turn south for Trinidad. This all worked out. Our second night out we were at a little airfield at Belem, South America, where I ran into a former Sunday school teacher from my home back in Sharon, PA. He was stationed there in Base Ops. The day after that we went on to Natal, staying there 36 hours before the hop to Ascension Island. The 36 hours was more than enough to get most of us a very short crew cut and a heck of a sunburn at the Natal beach.

A day after leaving Natal, we were on the runway awaiting take-off eastbound from Ascension Island, when the pilot was notified by the tower to return to Base Ops for a new briefing. There we learned that Gen. Doolittle exercised rank over Gen. Twining(?) in India, and ordered the Azon crews to the 8th Air Force, 2nd Bomb Division. We flew on to Liberia, Dakar, Marrakech, and over Portugal to our first airfields in England, Newquay on the Cornish coast. We flew the planes the next day to a field near Cookstown, Northern Ireland. We were there nearly two weeks getting planes fitted with ETO armor plate. It turned out to be a blessing!

We still didn’t know that most all 2nd Air Division missions were flown above 20,000! We did learn that quickly when we found ourselves with the 753rd Squadron at the 458th Bomb Group at Horsham Field, Norwich. Each plane had an Azon technician (Les Gruver was ours) assigned to it, as well as a crew chief. He did not go on missions, but kept the transmitters in top shape and supervised the bomb fins, receivers, and bomb loading. James Rand, one of the developers of the Azon bomb from Remington Rand Co., was with us in Florida, and at Horsham too, for three months. Our crew chief, Hal Bradshaw, was a superb mechanic. Several frosty mornings in late ’44 he fell off the wing while de-icing it, climbed up, de-iced more and fell off again! He was one hell-of-a fine man.

This bomb control technique with Azon (AZimuth ONly) was broadened by early 1945 to Razon, which enabled the control to be extended to “farther or shorter”. An obvious shortcoming was the need for visual control, a real hazard at altitudes under 25,000 feet and limited by weather. After a couple months trial in the ETO, the Azon crews were absorbed by the regular 458th organization. So much for the first of the “smart bombs”. Rumor had it they moved to India.

After a week or 10 days of relearning formation flying and picking up on group procedures, we were as ready (to see combat) as we were going to be. D-Day itself was a big surprise in that secrecy was so totally effective where we were. We were not on alert the night of June 5, slept in the next morning, and it was almost noon before we heard on Armed Forces Radio of the Normandy invasion landings.

Back to our mission #2 and the bridge of Peronne target. Our hearts pounded like bass drums and we sucked in our breath, turning on the IP at 16,000 feet altitude. Visibility was good and pilotage navigation (backed by D.R.) was not difficult. We were on the bomb run only two or three minutes until accurate flak seemed to go off all around us. In addition to explosions, air impact vibrations, black puffs, and white flashes, we heard the sounds of shrapnel (like handfuls of gravel) hitting the aluminum skin of the big B-24. We heard the pilot call, “Feather two, it’s hit.” Then he checked with Joe Schelzi the bombardier, to see if he had bombsight control of the plane, which he did. Joe controlled the flight until the target met the cross hairs.

Just before Joe released the bombs, we were whacked again by flak and everything seemed to go wrong. Pat yelled, “Feather four, it’s gone too!”

I looked out of my bubble windows, and on each side I could see a slowly wind milling prop. Bombs away and still getting knocked about by flak (in blue sky and sunshine), the third engine stopped. Word came over the intercom that the hydraulics weren’t working! Assistant Engineer Frank Limbert was directed to see what happened to the hydraulic system. Turret gunners were told to get out of the turrets since they had no hydraulic controls. I was asked for a heading NOW to home. I called back, “Take 310 degrees until I get you something better,” as we abandoned the flight plan with only one engine going, and altitude falling slow but sure. Frank called in that there were flak hole fuel leaks in the wing tanks over the bomb bay, one bomb hung up (armed), bomb bay doors jammed open, and the air ripping through the bomb bay blowing the leaking gasoline into a real steam room appearance! I established a location and gave a new heading for Dover. Ray Tomlinson, the nose turret gunner, got out of the useless turret as directed, with Joe’s help, and stood in the cramped space, with Joe staying seated on the floor. I told him to sit down with Joe so I had room to navigate. There was one more close burst of flak, and then I thought Joe had sat on my feet. I hollered, “Get off my feet, Joe!” He pulled on my arm and said, “It’s Tommy. He must be hit.” I pushed up the table top and Tommy was laying on my feet, dead.

Very quickly we discovered that a piece of flak (maybe the size of a peach pit) had entered the back of his neck in the small space below the steel helmet, and just above the top edge of the flak suit he had on. The flak had gone on up into his head and did not come back out. He died instantly and silently. We had only met him three weeks earlier, as he was a replacement for one of the gunners sent to India. A fine young fellow, 18 or 19, from Southern California.

In the meantime, Limbert dislodged the hung up bomb and with help from the waist gunners, hand cranked the bomb bay doors nearly shut. He also got the dozen flak-hole fuel tank leaks pretty well sealed with some material he came up with. There was a discussion on the flight deck about some of us bailing out. Pat decided he had nothing to lose in trying to start one of the three feathered engines, and lo and behold, at 7,000 feet one kicked back in! Apparently, one engine had been feathered in error, but it was a happy event for a change and no one complained. By this time we could see the channel ahead. Gas gauges indicated almost no fuel. Pat asked if there was a field to land at just across the channel. I checked my map and said, “Yeah, several” which my map indicated, although I had no runway length information on my maps.

Profile courtesy: Mike Bailey

We’d had no flak since the burst that killed Tommy, and no fighter attacks at all. We’d been a sitting duck for what must have been 20 minutes, but seemed like an hour. We prayed to get across the channel with our remaining gas, which we did. Pat said he could see an airfield off to the left a bit and I said, “Go for it.” Somehow one of the pilots raised the tower, and we were told to come in. With no hydraulics and no brakes, Pat set the lumbering bomber down with two engines (one each side) still going. We rolled off the end of the runway, over a pasture to a small depression where we stopped as the right wing tip hit the limb of a tree. An ambulance full of medics came out fast to assist us, but they could do nothing for Tommy. The rest of us had no wounds, just a few bumps and bruises. Within two or three hours we were on another B-24 (as passengers) going back to Horsham for debriefing. Pat and others went back to Kent (where we had landed) a couple of weeks later and brought our Bachelor’s Bedlam back to the 458th. It had 145 flak-hole patches (we counted them). The smallest was about two inches round and the biggest about eight inches squarish! The B-24 was a “bring ‘em back alive” Air Corps workhorse. Bet on it.

Two or three open ends remain. Other crew members on this second mission not already named were Fred Slocum, George Davis, Henry Jaber, plus Leo Sparkman and Stan Kowal. Ray Tomlinson was the only one of the original crew to pay the full measure of devotion during the war. Tommy was buried at Madingley Cemetery near Cambridge, and I have been back there with Frank Limbert twice to pay my respects. My wife, son, and I were there together on another trip.

The first mission was so very easy we were almost shocked. We actually laughed at a few stray black flak puffs that seemed a half mile away! It was not what air combat and bombing missions were supposed to be like. It wasn’t. It did not help us get ready for the second mission.

You will recall we’d arrived in England in suntans with new crew cuts. We had no winter uniforms at all. Six months before, I had bought all new pinks and greens, overcoat – the works. All were gone to India in a footlocker, by ship. The airmen [enlisted men] (rightly so) were issued new winter uniforms. The rest of us [officers] had to go to London or Burtonwood to buy our replacement uniforms. It took three or four months for the crew cuts to grow out. My footlocker (never unlocked) got back to me in Pennsylvania in January of 1946. I was amazed to find no cobwebs, no mold, no bugs – everything pressed and clean, like the day it was packed.

Regarding the Irish-armor-plate-blessing mentioned earlier. On our 12th mission (to Hamburg, Germany in early August) flak was awful. Pilot Pat McCormick got a nasty knee wound. (He was grounded for six weeks recovery – three in hospital). I have a forever image in my head, seeing five or six lurching planes blown to bits, or reduced to scrap and three or four parachutes each, descending through heavy black flak. An unexploded shell hit the bottom side of a piece of A-plate I was standing on, knocked four bolts loose, but did not pierce it and wash me out! My children and grandchildren are grateful to the Irish, as am I.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Harry N. Craft was born Harry N. Crabbe and was known as Harry Crabbe until long after WWII, when in 1957 he legally changed his last name to Craft. All USAF and official records reflect this.

2ADA Journal

Additional Images

Scroll left or right to view images

Disposition

B-24JAZ-155 CO 44-40287 BACHELOR’S BEDLAM

NMF

RCL: J J4 (753)

Name changed from BACHELOR’S CLUB to BACHELOR’S BEDLAM.

Lead aircraft.

RCM equipment.

Repaired at Stansted, Essex, 15 – 24 Jun 44 – # 1 engine.

Repaired at Thorpe Abbotts, 10 – 20 Nov 44 – # 4 engine.

On 14 Mar 44 at Horsham St. Faith, a waist gunner preparing for a mission on board 42-50555, failed to check for ammunition in his gun before pulling the trigger. Several rounds went off which ricocheted into the bomb bay and left wing tank of 44-40118, igniting an incendiary bomb and gas tanks. This set 44-40118 afire, exploding the bomb load which completely destroyed the aircraft.

It also caused major damage to 44-40273, 44-40285, 44-40287, 42-100408, 42-50555 and 44-10602 and minor damage to 42-110141, 44-40277 and 42-50912. The damage was repaired at Horsham St Faith 14 Mar 45 by 469th Sub Depot.

RZI?

(Info courtesy: Tom Brittan)