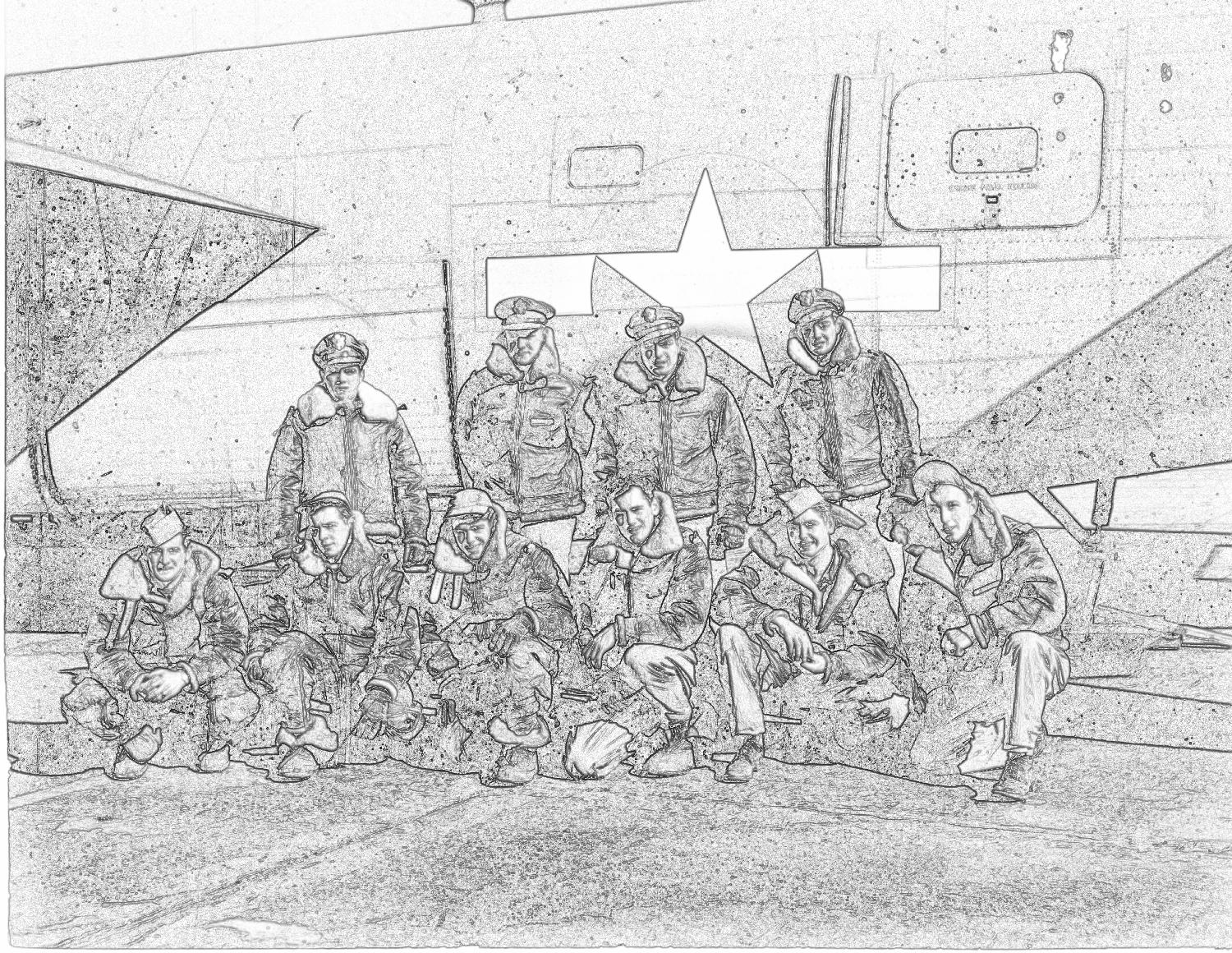

Glass Crew – 755th & 752nd Squadrons

Crew Photo Needed

Completed Tour – Crew Members as of October 23, 1944

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Crew Position | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1Lt | Searcy C Glass, Jr | 701920 | Pilot | 06-Nov-44 | CT | Rest Home Leave |

| 2Lt | John R Ewing | 1996106 | Co-pilot | Oct-44 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

| 1Lt | John S Holodak | 703258 | Navigator | 09-Apr-45 | POW | Shot down - Flak, with Abramowitz |

| 1Lt | David C Jelinek | 698016 | Bombardier | Jan-45 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

| T/Sgt | Frank L Sanborn | 31313040 | Radio Operator | 06-Nov-44 | UNK | Rest Home Leave |

| T/Sgt | Rene R Morin | 31286213 | Flight Engineer | Nov-44 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

| T/Sgt | William C Madden | 11017530 | Aerial Gunner | 06-Nov-44 | UNK | Rest Home Leave |

| S/Sgt | Donley R Koon | 34645767 | Aerial Gunner | 06-Nov-44 | UNK | Rest Home Leave |

| S/Sgt | Harry A Rea | 36731503 | Armorer-Gunner | Nov-44 | CT | Awards - OLC to Distinguished Flying Cross |

| T/Sgt | Leon R Santoni | 39125602 | Gunner-Flight Engineer | Dec-44 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

Searcy Glass was assigned with the crew of 2Lt Joseph H. French, to the 755th Squadron on June 7, 1944. They flew their first mission four days later. During the busy month of June the crew completed almost 1/3 of their required missions.

At some point in mid-July, after completing 9 or 10 missions as co-pilot, Searcy Glass, was given his own crew to command. While the original composition of Glass’ crew is unknown, it is likely that it was made up of men whose crews had either been lost or completed their tours. In October, when the 755th Squadron became the Group’s “Lead” squadron, both French and Glass were transferred out – French to the 754th and Glass to the 752nd. French’s crew was mostly intact, with three crewmen different from that assigned.

Glass’ crew at this point in time (late October 1944) was made up almost entirely of men from several different crews and two ground men who had been reclassified in order to fly combat missions. The only exception was original crew member Sgt Leon Santoni, who appears to have stayed with Glass.

1Lt John R. Ewing – Co-pilot. Originally assigned with 1Lt Charles J. Hauser crew on June 3, 1944.

1Lt John S. Holodak – Navigator. Believed to have been original member of Lt Samuel T. Gibson crew. Shot down with Abramowitz, April 9, 1945.

1Lt David C. Jelinek – Bombardier. Originally the bombardier for Lt Charles W. Quirk crew, assigned in May 1944.

T/Sgt Frank L. Sanborn – Radio Operator with Lt Arthur F. Kenyon crew, assigned June 6, 1944.

T/Sgt Rene R. Morin – Flight Engineer. Originally assigned with 1Lt Dudley McArdle crew in May 1944.

T/Sgt William C. Madden – Originally an Administrative NCO with HQ. Transferred to 755BS and reclassified as Aerial Gunner.

S/Sgt Donley R. Koon – An individual replacement “Airman Basic” who was with HQ. Transferred and reclassified as Aerial Gunner

S/Sgt Harry A. Rea – Aerial Gunner. Original crew unknown.

Glass took part in the Truckin’ Missions that occurred in September 1944, and resumed combat flying in October. Most of the crew’s missions for that month and the months that followed were to targets in Germany. Searcy Glass finished his tour in early January and was sent on Rest Home leave.

Missions

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20-Jul-44 | EISENACH | 95 | 1 | 42-51179 | P | J3 | 20 | DUSTY'S DOUBLE TROUBLE | |

| 24-Jul-44 | ST. LO AREA | 97 | 2 | 42-51097 | T | J3 | 33 | UNKNOWN 022 | |

| 25-Jul-44 | ST. LO AREA "B" | 98 | 3 | 42-50320 | ? | J3 | 29 | UNKNOWN 018 | |

| 04-Aug-44 | ROSTOCK | 103 | 4 | 42-52441 | I | J3 | 46 | LAST CARD LOUIE | |

| 05-Aug-44 | BRUNSWICK/WAGGUM | 105 | 5 | 42-95183 | U | J3 | 30 | BRINEY MARLIN | |

| 07-Aug-44 | HAMBURG | 107 | 6 | 42-51179 | P | J3 | 28 | DUSTY'S DOUBLE TROUBLE | |

| 09-Aug-44 | SAARBRUCKEN | 109 | ABT | 42-95120 | M | J3 | -- | HOOKEM COW / BETTY | GAS STREAMING OUT ON T/O |

| 13-Aug-44 | LIEUREY | 112 | ABT | 42-52441 | I | J3 | -- | LAST CARD LOUIE | #3 ENG OIL PRES |

| 16-Aug-44 | MAGDEBURG | 115 | 7 | 42-100425 | O | J3 | 27 | THE BIRD | |

| 24-Aug-44 | HANNOVER | 117 | 8 | 42-51097 | T | J3 | 39 | UNKNOWN 022 | |

| 26-Aug-44 | DULMEN | 120 | 9 | 42-51097 | T | J3 | 41 | UNKNOWN 022 | |

| 01-Sep-44 | PFAFFENHOFFEN | ABN | -- | 42-51097 | T | J3 | -- | UNKNOWN 022 | ABANDONED |

| 09-Sep-44 | MAINZ | 124 | 10 | 42-51179 | P | J3 | 36 | DUSTY'S DOUBLE TROUBLE | |

| 11-Sep-44 | MAGDEBURG | 126 | ABT | 41-29352 | K | 7V | -- | WOLVE'S LAIR | #2 SUPER CHG OUT |

| 12-Sep-44 | WELFORD to CLASTRES | TR01 | -- | 42-100425 | O | J3 | T1 | THE BIRD | CARGO |

| 19-Sep-44 | HORSHAM to CLASTRES | TR03 | -- | 41-28785 | B | 44BG | T2 | NOT 458TH SHIP | ON LOAN FOR TRUCKIN' |

| 22-Sep-44 | HORSHAM to CLASTRES | TR06 | -- | 42-99997 | P | 755 | T3 | NOT 458TH SHIP | TRUCKIN' MISSION |

| 29-Sep-44 | HORSHAM to LILLE | TR12 | -- | 42-7629 | A | 755 | T9 | NOT 458TH SHIP | TRUCKIN' MISSION |

| 30-Sep-44 | HORSHAM to LILLE | TR13 | -- | 42-7642 | N | 44BG | T11 | M'DARLING | TRUCKIN' MISSION |

| 05-Oct-44 | PADERBORN | 128 | 11 | 42-51196 | Q | J3 | 1 | THE GYPSY QUEEN | |

| 07-Oct-44 | MAGDEBURG | 130 | 12 | 44-10602 | A | J3 | 9 | TEN GUN DOTTIE | |

| 09-Oct-44 | KOBLENZ | 131 | ASSY | 41-28697 | Z | Z5 | A20 | SPOTTED APE | ASSEMBLY CREW |

| 14-Oct-44 | COLOGNE | 133 | 13 | 42-51196 | Q | J3 | 4 | THE GYPSY QUEEN | |

| 19-Oct-44 | MAINZ | 136 | 14 | 42-51196 | Q | J3 | 5 | THE GYPSY QUEEN | |

| 30-Oct-44 | HARBURG | 139 | 15 | 42-51206 | S | 7V | 12 | THE PIED PIPER | |

| 04-Nov-44 | MISBURG | 141 | 16 | 42-51206 | S | 7V | 14 | THE PIED PIPER | |

| 21-Nov-44 | HARBURG | 148 | 17 | 42-51206 | S | 7V | 21 | THE PIED PIPER | |

| 25-Nov-44 | BINGEN | 149 | 18 | 41-29567 | G | 7V | 5 | MY BUNNIE / BAMBI | |

| 26-Nov-44 | BIELEFELD | 150 | NTO | 42-52457 | Q | 7V | -- | FINAL APPROACH | NO TAKE OFF |

| 30-Nov-44 | HOMBURG | 151 | 19 | -- | -- | -- | -- | No FC - Sqdn Rec's | |

| 06-Dec-44 | BIELEFELD | 153 | 20 | 42-51206 | S | 7V | 22 | THE PIED PIPER | |

| 11-Dec-44 | HANAU | 155 | 21 | 42-51206 | S | 7V | 24 | THE PIED PIPER | |

| 18-Dec-44 | KOBLENZ | REC | -- | 42-51206 | S | 7V | -- | THE PIED PIPER | RECALL DUTCH ISLE |

| 24-Dec-44 | SCHONECKEN | 157 | 22 | 42-51206 | S | 7V | 26 | THE PIED PIPER | |

| 30-Dec-44 | NEUWIED | 161 | 23 | 42-51206 | S | 7V | 28 | THE PIED PIPER | |

| 31-Dec-44 | KOBLENZ | 162 | 24 | 42-51206 | S | 7V | 29 | THE PIED PIPER | |

| 03-Jan-45 | NEUNKIRCHEN | 165 | 25 | 42-95165 | L | 7V | 54 | COOKIE | |

| 07-Jan-45 | RASTATT | 166 | 26 | 42-51110 | M | 7V | 63 | TOP O' THE MARK | |

| 10-Jan-45 | SCHONBERG | 168 | MSHL | -- | -- | -- | -- | MARSHALING CHIEF |

S/Sgt Harry A. Rea – Distinguished Flying Cross

HARRY A. REA, 36731503, Staff Sergeant, Army Air Forces, United States Army. For extraordinary achievement, while serving as nose turret gunner of a B-24 aircraft on a bombing mission to Germany, 7 October 1944. Sergeant Rea received painful face injuries and head wounds as his aircraft sustained a direct hit from anti-aircraft fire on the bomb run. With utter disregard for his personal safety, Sergeant Rea remained at his position and successfully released his bombs on the target. Satisfied that he had fulfilled his assigned duty, Sergeant Rea received first aid treatment. The courage, devotion to duty and perseverance displayed by Sergeant Rea on this occasion reflect the highest credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of the United States. Entered military service from Illinois.

(2BD GO290 Nov 5, 1944)

1Lt John S. Holodak – Navigator

“From the Beginning of my Capture to the Return Home”

Interviewed by: Alex Holodak

I joined the army because my high school days were in a military academy in New York. This prep-school was called Christian Brothers Academy. It was there where I learned basic infantry. And I was a member of the school’s cavalry troop as a follow up, to this high school program. I participated in a summer training program called Citizens Military Training Camp. Where I continued my education in military matters and that is where I became eligible for a commission in the United Stated infantry, reserve.

After completing this background, I entered Manhattan College in New York City where I received a bachelor’s degree in Business Administration. I graduated in May of 1941 and worked in my father’s cooperage business for the next several months. When I enlisted in the United States Army/Air Force Cadet Training program, I was called to active duty in February of 1943, eleven months after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

From February of 1943 to December 1943, I received basic, primary, and advanced training for navigation. On December 23rd of 1943 I was commissioned to second Lieutenant and sent to Colorado Springs where I joined the other members of my B-24 Liberator Bomber Crew. On April 8th my new crew flew from Topeka, Kansas to West Palm Beach, Florida and thence via the Southern route to Puerto Rico, British Kiana, and Forteleza, Brazil; to Dakar, Africa; to Marrakesh, Morocco, then onto Belfast, Ireland. From Belfast we were ferried to Scotland and by train down to our assigned combat base, the 458th bomb group, 752nd squadron at Horsham, St. Faith; Norwich, England. We arrived at this base sixteen days after leaving the United States and I flew my first combat mission on May 23rd of 1944.

On July 11th, my original crew [1Lt Samuel T. Gibson] went “Missing in Action” and has never been heard from since. By some stroke of luck or who knows… God’s will, I was grounded from that flight and asked to do the group navigators briefing. After this disaster, I was assigned to another crew and removed from one of the missions because of a serious cist on my left ear lobe. That crew was on its seventeenth mission as was my original crew and the target area for both of them were in the Munich, Germany area. The second crew was shot down over its target and once again I escaped.

When I first arrived in England, the tour of duty was twenty-five missions. By the time I got to twenty-two missions, the requirement was raised to twenty-eight, and as I approached that number it was increased to 30, then when I got to that number it was increased again, to 35. I thought it would never end, but victory was in sight. Between combat missions I flew a number of special missions to France delivering specially designed gasoline tanks filled with gasoline to support General George Paton’s fast moving tanks and armored divisions. There was no credit for these missions although they were extremely dangerous, there was no combat credit for these missions. Once again I survived… But on April 9th, 1945 on my 32nd combat mission [with 1Lt Leonard Abramowitz] to bomb a German jet base at Lechfeld. My plane was struck by German anti-aircraft fire with a direct hit between the number 2 engine and the fuselage. The electrical system was damaged; the plane was afire with flames coming from the command deck forward along the catwalk to my position in the nose of the B-24. Oddly enough Lechfeld airfield was just a few miles from Munich, the sight my two former crews final missions.

Lechfeld Airfield (target for April 9, 1945) can be seen, with bombs bursting, beneath Final Approach

I was able to extract my nose gunner, Alan Rupp [right] from his turret; assisted him with hooking up his parachute to his harness as he assisted me hooking up my parachute to my harness. Since the electrical system was inoperative, we could not lower the nose wheel door which was our only available exit. In a matter of seconds the plane exploded at twenty-three thousand feet. I was knocked unconscious and awoke in a free falling fetal position plummeting towards the earth. I was able to see other members of the crew whose parachutes had opened so I knew there were some other survivors. As I fell I purposely withheld pulling the rip cord, which opens the chute, because it was such a clear day that the Germans were shooting at the chutes and I made several observations while in this free fall. Number one, the wind resistance did not cause my eyes to tear. Another thing was at twenty thousand feet – which was our bombing altitude, was around 67 degrees below freezing. The temperature change from that altitude is approximately 3 degrees for each thousand feet of fall. So at ground level it would have be below 0 degrees, but at the level I was at, and my fall, I was perspiring tremendously and I could not understand how that could be. When I reached what I thought was five thousand feet, I pulled my rip cord and opened my chute. I was floating down almost in the direct line towards the target that we just bombed.

Other succeeding groups were still dropping their bombs on the same target. I could hear and feel the pressure as they fell from the sky. I thought… God wouldn’t be irony if one of these succeeding bombs were to take me down with it. Fortunately I am here to tell the story, but once my chute opened I had a chance to manipulate the direction of my fall so that the wind would be at my back when I landed, allowing me hopefully to land and be pulled forward till the air spilled out of the chute. But before this happened I reached around to my back instead of perspiration I found a handful of blood, then I realized I was wounded.

The closer I got to earth the more visible the activities on the ground were. Soldiers, rifles in hand, surrounding other parachutists as they landed, and circling the area where they figured I would land. I had never parachuted before. I can only say that, under any other circumstances it might have been just a thrilling experience, but in my case it was life saving. People ask, “What is it like as you land?” You hit the ground as if you had taken a jump from a 32 foot height and in order not to break your legs or your back, you give yourself some slack on each of the risers which you release simultaneously just before your feet hit the ground, this forces air back up to the chute and gently lets you down.

Now I am surrounded by German infantry men, in a big circle, possibly about 150 yards away as I hit the ground. I landed in a freshly plowed field and I was able to be dragged a short distance at which time I could release the parachute from the harness rings. At this point I realized my injury was much more serious than I have even dreamed… I could not stand up. The first person to reach me was a farm lady, carrying a bucket of spring water from the local spring on her property. She approached me directly, knelt down, lifted my head up, and drew a ladle of spring water from her bucket.

Within seconds, several German soldiers reached me. Screaming at the lady in German to get clear of me, because I might have been booby trapped or have had a weapon to use on her. She paid no attention to them and they had to drag her away from me. Then the command, “Raus!” I don’t know German, but I knew what they meant, yet I could not respond. The farm woman was trying to explain to them that I couldn’t get up. At which point one of them turned me over and then they realized I was bleeding and was badly injured. He knelt down, took a pack of cigarettes out of his pocket, asked if I would like to have a smoke, put the cigarette in my mouth and lit it. While we waited for a transport of some kind to pick me up, the same soldier offered me another cigarette. I learned later on that his ration of cigarettes as a combat infantryman was two cigarettes a day. He gave them both up to me. This was my first experience in the first moments of my capture. And it was one of compassion, which I did not expect.

A flat bed truck came by within a half hour to pick me up to transport me to what was left of the administration building on the airfield which we had just bombed. I was taken down three or four flights of stairs by two men. One holding a lantern and down in this subterranean area they opened a large creaking door and threw me in, onto the dirt floor, slamming the door behind them. It was pitch black and damn cold. I laid there freezing and shivering in and obviously trauma condition and then thought I heard someone breathing. I finally called out, “Who is there?” And a most familiar voice responded, “Is that you Jack?” It was my pilot. Lenny Abramowitz; the next voice was that of Ned Salanski, my co-pilot. Then John Barillaro, our flight engineer. Then there was one more voice which came from Lt. Bill Hauck, a P51 fighter pilot who was protecting our mission when his plane ran out of fuel and he was forced to land and was captured. He still had his fur lined flight jacket. Mine had been taken from me at the time of my capture. We then heard two men at the door and the door opening with a man coming in with a lantern followed by another person who turned out to be a medical corpsman. He offered to remove shrapnel particles from my back and my right foot. When he opened his kit of instruments, even in this dim lit lantern light I thought the instruments looked rusty, and I refused to let him probe at all. In that brief period I saw that there were several double decker bunks in this cell. They had wooden slats as mattresses. My new found friend Bill Hauck helped get me up to the first level bunk. I was shivering intensely, so bad my teeth were chattering. He removed his flight jacket and put it around me and then got up to the bunk, threw his arms around me and kept me warm till some hours later, then one by one, taken upstairs to be processed to be delivered to the German POW camp.

In a few hours we were given a single slice of German dark rye bread, which I later learned was partially made of saw dust. It was sour rye and the one slice took me all day to bite into and swallow. I received one cup full of cold water that day. Because of my own injury, and what I thought was a more serious injury to my engineer, I devised a plan in my own mind to guarantee us medical attention at the nearest German hospital. Two men were assigned to take the four of us to our POW camp. One spoke only German the other spoke German and a little French. I had 6 years of high school and college French, which I never used until then. I was able to converse with the more fluent German in French and to learn what our destination was. At this moment I probably turned gray because we were headed for Ingolstadt to be interrogated there before proceeding to the POW camp. Only I knew that Ingolstadt was an alternate target that was to be bombed by us in the event that our Lechfeld mission could not be accomplished with foul weather. We were then supposed to drop our bombs regardless of weather conditions on our target Ingolstadt.

I managed to convince the fluent German that we had to go to a hospital for me and my engineer both of whom were still bleeding and no attention given to us. We were being transported on a flat bed wagon draw by two horses with bales of hay on which we were resting. One man drove the team of horses while the other pointed his rifle at us. We were taken to Augsburg to the nearest hospital where the senior medical officer came out of the hospital to inquire what he could do for us. This man in particular spoke perfect English; in fact he was educated in the United States. I being the senior officer in rank was brought up the steps to a wheelchair which this German doctor, a full Colonel, personally took me in while the others waited outside. The hospital was a warehouse four stories high that had been converted to temporary hospital use. The Colonel took me to the freight elevator and adjusted the pullies, we elevated to the fourth floor. When the gate opened I saw a level square floor about 200×200 feet filled with rows and rows of army cots all with moaning patients. The Colonel explained that these were all German civilians that were injured when this so called “Open City” was bombed they were all amputees, some of them multiple amputees, and the Colonel explained that these people were operated on without the benefit of anesthesia. The Germans did not have any supplies; in fact, they did not have thermometers, alcohol, or gauze bandages. What they did have was rolls of crinkle paper like we see for birthday decorations. The Colonel looked at me and said, “What can I do for you Lieutenant?” I said, “Get me out of here now!”

We then went to the Augsburg train station; the depot was loaded with civilians, running in all directions, trying to leave this torn city for anywhere safer. When we entered the depot, the Sargent went over to the opposite side of the building to get us transferred to Ingolstadt. The Private was left to guard us four, at which point some very angry German men came across the station floor towards us and threatened the four of us that the Private hold us off with his rifle, but he was frightened himself. The brazen leading of this group picked on the shortest number of the four of us, my engineer, John Barillaro, he took a deep breath and he spat out in the face of my engineer, John was so angry he did a knee bend, took several deep breaths and standing up, almost nose to nose with the German. John coughed up a “lunger” and spat it right in his face. The German was so shocked and backed off and went back to the other side of the station and we proceeded to the assigned train. We were put into a compartment by ourselves and the train proceeded to Ingolstadt no more than 15 to 18 kilometers from what I could tell. Three times during that short trip the train came to a short stop when American P-47 fighter planes strafed the cars. Each time the train stopped everyone evacuated to the ditches alongside the tracks, leaving me alone in the compartment. We arrived on the outskirts of Ingolstadt at 5pm. Just as the air raid sirens went off for a bombing by American bombers. The very thing I anticipated and tried to avoid.

We never got into the city. Our captors commandeered another wagon and two horses deciding to take us directly to the prison camp, Stalag number 7A, Mooseburg, Germany. During that part of the trip, I was told that president Roosevelt had just died. The German who told me this was crying. He said, “You have lost a great leader, and I feel sorry for you. We have lost the war.” When we arrived at the prison camp we were driven from one compound to another, each compound consisted of two barracks, separated by a urinal and a water faucet. Each building housed 200 prisoners, even though these barracks were originally devised for 40 trainees. The bunks within were four high with wooden slats with no mattresses. We went at least a half-mile through these compounds before finding one that had room for even one more prisoner. So at this point the four of us were separated. The building which I was brought to had no more bunks, but I couldn’t move or get up anyways so I slept on the floor near the door on a pagliacci, a straw filled sack. One man in our compound happened to be a doctor who was a Nisei, a Western Japanese American, who was sent to war during the time when the Japanese Americans were sent to camps. He had no instruments, no thermometer, no iodine; no nothing… he was just a doctor. He could take your temperature and pulse with his hand and that was all. I learned in the next twenty days how imaginative and ingenious our allies were during this common imprisonment. They were able to communicate with Great Britain by makeshift radio transmitters. They made wood burning stoves with forces draft which allowed them to boil water and in some cases even bake from ingredients that they found in Red Cross food parcels that were the only staple available to them during the war. When there were no Red Cross parcels, they served different kinds of make shift food mainly sauerkraut, boiled potatoes, potato skins, turnips, and occasionally these ingredients coupled with horse meat or rabbit that they would make a stew out of. On two occasions during my twenty day experience as a POW none of the above ingredients were available and a special meal was prepared by mowing the conjoined fields of grass and cooking it in a soup or stew, with all of the bugs that were in the ground, grasshoppers, ants, grubs, etc. This meal was called “Green Dragon Stew”. Men flicked the bugs out of the so called stew and they’d eat the grass. Six months later in a gourmet store on Madison Ave. New York City, I saw them offering chocolate covered ants, grasshoppers, and a variety of other bugs in chocolate, as a very useful delicacy and very expensive.

On April 29th 1945, my twenty day ordeal ended when General George Paton entered our camp and welcomed us back as repatriated Americans. There were so many prisoners in [Stalag]7A that it took days to arrange transportation. We were flown to France to Camp Lucky Strike, irony indeed. Our departure point was Ingolstadt airfield. At Camp Lucky Strike we were deloused, given hot showers with real soap, and towels, new uniforms, including underwear, shoes, and socks. My injuries were evaluated and I had a temporary partial paralysis. I boarded a Navy Victory Ship called the General Simpson and departed LeHavre, France (just above Normandy). The day before I left Camp Lucky Strike, the war in Europe ended and [the] Associated Press war correspondent [Edward Kennedy] who had revealed the war’s end the day before General Eisenhower wanted to make it known, was chastised and dismissed from the news corps and returned to the States on the same ship that I was on. Our route took us to Trinidad where we left members of the 72nd Airborne Division who were being reassigned to the Pacific theatre. It took us twenty-two days to finally reach New York Harbor and the welcoming arms of the beautiful Statue of Liberty. I came home to see for the first time my first born son, John, who was then several months old, and to my lovely bride, Mildred.

I have never lost the pride and the feeling of patriotism and the love of fellow Americans that I experienced during the war and that even today as a past commander of the Hudson Valley chapter of the American ex-prisoners of war, I would feel honored to serve my country again. There is no other nation in the world that can claim democracy in every sense of the word of its people. We have the right to protest, we have the right to disagree, we have the right to enjoy our religious beliefs, and to respect others, and to walk proudly as free men.

(Courtesy: Alex Holodak)