Duke Crew – Assigned 754th Squadron – December 21, 1944

(Photo: Jason Garcia)

Shot down February 22, 1945 – MACR 12675

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Crew Position | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2Lt | William A Duke | 0825602 | Pilot | 22-Feb-45 | MUR | Murdered by German police |

| 2Lt | Archibald B Monroe, Jr | 0834852 | Co-pilot | 22-Feb-45 | MUR | Murdered by German police |

| F/O | Richard M Eselgroth | T132898 | Navigator | 22-Feb-45 | POW | Stalag Luft III |

| F/O | Albert E Miller | T7059 | Bombardier | 22-Feb-45 | POW | Stalag Luft III |

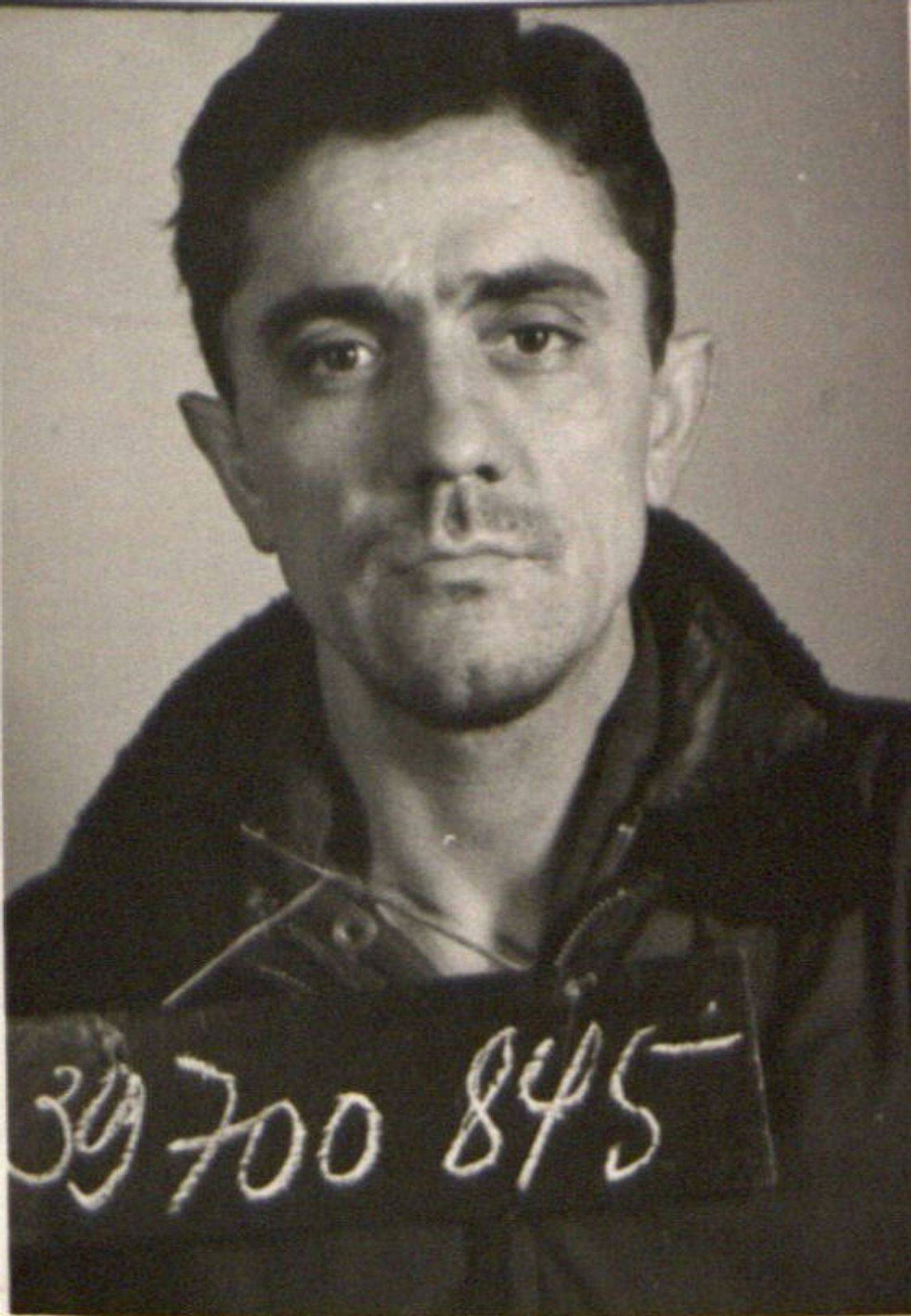

| Sgt | Albert M Lucas | 39700845 | Radio Operator | 22-Feb-45 | POW | Camp Unknown |

| Sgt | Baldamore Garcia | 39289589 | Flight Engineer | 22-Feb-45 | KIA | Died of wounds |

| Sgt | Charles Frazer, Jr | 18232071 | Waist Gunner | 22-Feb-45 | MUR | Murdered by German police |

| Sgt | Carl L Johnson | 16174596 | Nose Turret Gunner | 22-Feb-45 | POW | Camp Unknown |

| Sgt | Charles E Grotz, Jr | 13190224 | Waist Gunner | 22-Feb-45 | POW | Camp Unknown |

| Sgt | Alessandro D Panarese | 11122931 | Tail Turret Gunner | 22-Feb-45 | POW | Wounded - Camp Unknown |

2Lt William A. “Billy” Duke’s crew was assigned to the group a few days before Christmas 1944. After a brief indoctrination period, they began flying missions on January 21, 1945. The crew was able to get in five combat missions in a one month period.

The crew aborted two additional missions due to mechanical problems. On February 3rd, flying B-24J 42-95120 Hookem Cow, the ship experienced engine trouble causing the numbers 1 and 2 props to run away. On the February 15th mission to Magdeburg, the crew aborted in the vicinity of Splasher 5 after repeated attempts to raise the landing gear failed.

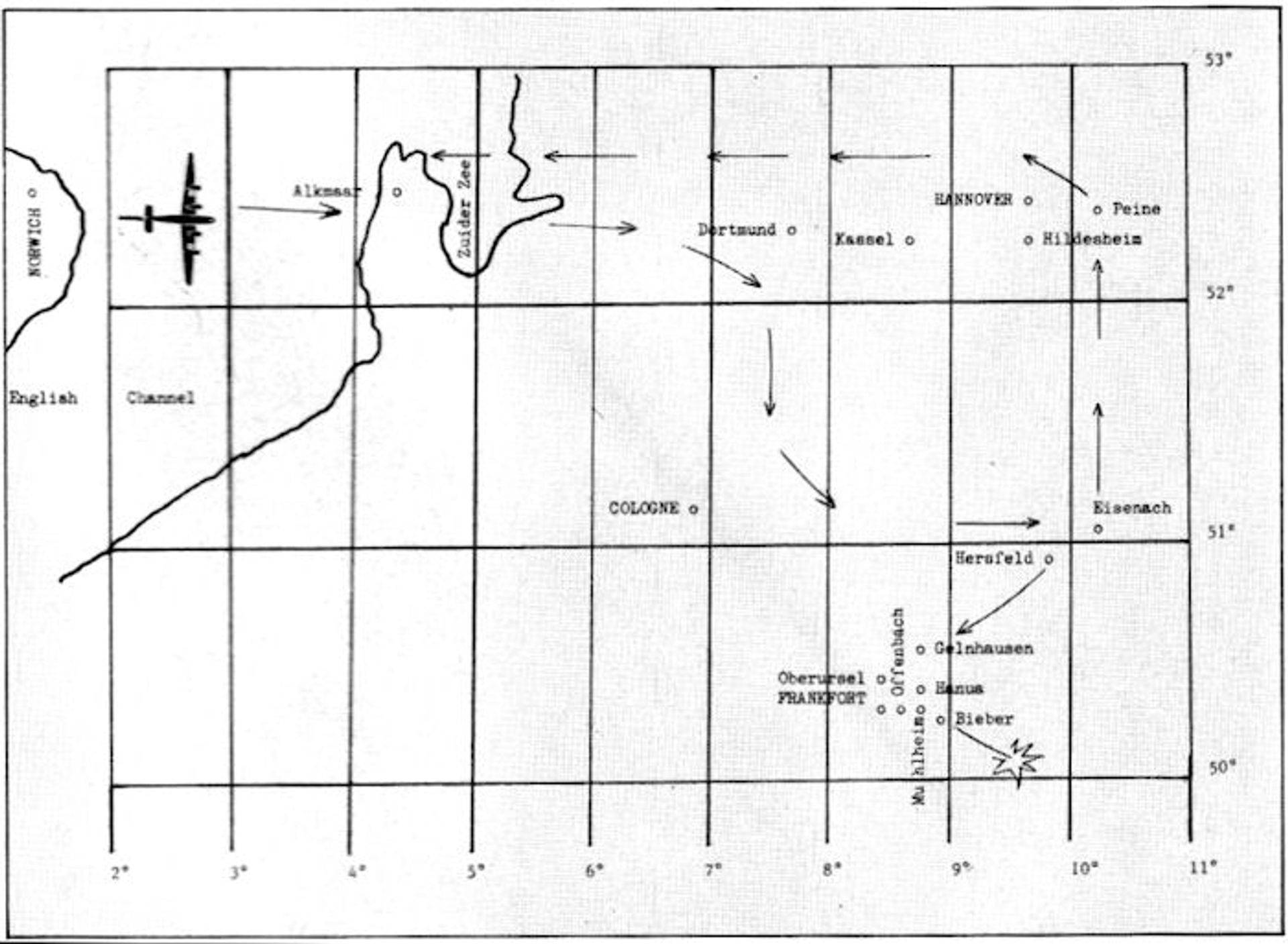

Their sixth mission to the marshalling yards at Peine and Hildesheim Germany on February 22, 1945 is documented below.

————————-

MACR 12675

A/C 491 peeled off from formation before the I.P. at approximately 5056-0947. He jettisoned his bombs, made 180 degree turn, headed back for France. All engines working and in no apparent trouble.

WC 12-2000

When the war ended, the War Crimes Branch looked into the case of the Duke Crew.

Missions

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 07-Jan-45 | RASTATT | 166 | MSHL | -- | -- | -- | -- | MARSHALING CHIEF | |

| 21-Jan-45 | HEILBRONN | 173 | 1 | 42-110141 | U | J4 | 35 | BREEZY LADY / MARIE / SUPERMAN | |

| 28-Jan-45 | DORTMUND | 174 | 2 | 44-40126 | L | Z5 | 45 | SPITTEN KITTEN / SKY TRAMP | 2000# BOMB LOAD |

| 29-Jan-45 | MUNSTER | 175 | 3 | 44-10491 | I | Z5 | 2 | THE IRON DUKE | |

| 03-Feb-45 | MAGDEBURG | 177 | ABT | 42-95120 | M | Z5 | -- | HOOKEM COW / BETTY | ABORT #1, 2 PROPS |

| 14-Feb-45 | MAGDEBURG | 181 | 4 | 44-10491 | I | Z5 | 7 | THE IRON DUKE | |

| 15-Feb-45 | MAGDEBURG | 182 | ABT | 42-95108 | B | Z5 | -- | ENVY OF 'EM ALL II | ABORT LANDING GEAR |

| 17-Feb-45 | ASCHAFFENBURG M/Y | REC | -- | 44-10491 | I | Z5 | -- | THE IRON DUKE | RECALL - WEATHER |

| 19-Feb-45 | MESCHADE | 184 | 5 | 42-51199 | A | Z5 | 24 | UNKNOWN 023 | |

| 22-Feb-45 | PEINE-HILDESHEIM | 186 | 6 | 44-10491 | I | Z5 | 12 | THE IRON DUKE | SHOT DOWN BIEBER, GER |

Duke Crew & Top O’ The Mark

(Photo: Richard M. Eselgroth)

Duke Crew with unidentified aircraft and a blown engine

(Photo: Jason Garcia)

February 22, 1945

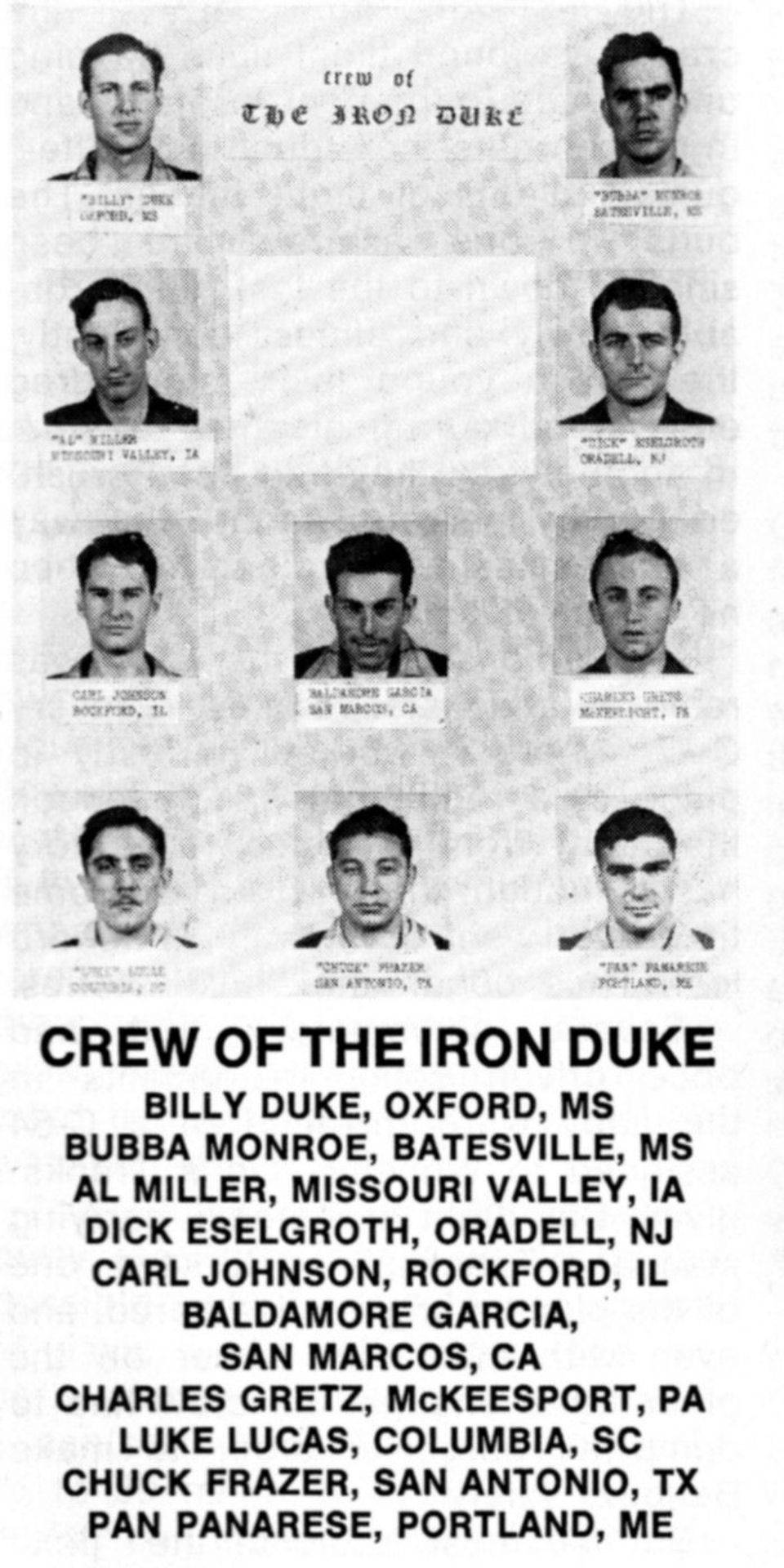

THE IRON DUKE & ITS CREW

The story of a B-24 crew shot down over Europe and their adventurous survival

By George Reynolds

This article first appeared in B-24 Liberator Commemorative Edition, Vol. 2 No. 1 1995

It is reproduced here with photos by the kind permission of the author.

In the predawn hours of 22 February 1945, throughout the European Theater of Operations, ground and air crewmen were preparing for Operation Clarion—a maximum effort to deliver a coup de grace to the Nazi rail and communications systems. Some 2500 bombers and fighters of the U.S. Eighth, Ninth, Twelfth, Fifteenth Air Forces and the Royal Air Force were participating in the largest combined air campaign since D-Day over central and southern Germany and the Mediterranean area. However, today’s smaller, widely dispersed targets dictated individual Group sorties rather than a giant strike force that attacked Normandy. Weather was to be favorable.

A base “somewhere in England”: (Air Force Station 123, near Norwich and home to the 458th Bombardment Group, Heavy), it was one of the Eighth’s fourteen fields in East Anglia to launch B-24 Liberator elements in the massive operation. Their objective: Railroad marshalling yards at Peine and Hildesheim in central Germany.

At dawn a heavy overcast verified the local weather was not as forecast. But a weather reconnaissance P-51 had reported clearing conditions over the Continent and, at 0900 hours, thirty-eight B-24s of the 458th departed on its most unusual mission in eleven months of combat. Instead of the normal 25,000-foot flight level, bombing altitude was 10,000 feet. And worse, there would be no clouds to screen the bombers from those deadly flak batteries awaiting in Germany.

The Liberators climbed over Alkmaar, Holland, and the Zuider Zee to 22,000 feet before breaking out for assembly into combat structure. To avoid midair collisions in the clouds, the aircraft had scattered, but eventually formed into two boxed forces of sixteen and eighteen ships. During the climb, four of the war-weary planes aborted with mechanical trouble. The sixteen-plane element headed for Peine, the other for Hildesheim.

Large breaks began appearing in the undercast over Germany, and the sixteen B-24s descended to 10,000 feet, heading southeasterly. Dortmund slipped by to the left while the formation skirted known flak areas. Crewmen marveled at how plainly they could see enemy territory today after flying over it “blind” in the past. Cologne passed to their right. Ahead, the initial point (pivotal), Eisenach, loomed on the horizon. Here, the armada would turn northward with their bombsights on Peine, but a smaller town had to be crossed first.

It was clear over Hersfeld when a puff of ranging flak crumpled under the formation where planes number 42-51215 B [flown by 2Lt Joseph E. Szarko and crew] and 44-10491 I brought up the rear. Suddenly, 215-B received a disintegrating blast in its bomb bay. One wing twirled away as though in slow-motion, and a parachute emerged from the waist section. But that crewman was drawn back into the inferno as a fiery mass plunged all ten men earthward.

Aboard 491-I, nicknamed Iron Duke, were the pilot, 2Lt William A. “Billy” Duke, 21; copilot, 2Lt Archibald A. “Bubba” Monroe, 21; navigator, F/O Richard M. “Dick” Eselgroth, 24; bombardier, F/O Albert E. “Al” Miller, 23; and the radioman, Sgt Albert M. “Luke” Lucas, 38. Other crew members included the flight engineer, Sgt Baldamore Garcia, 24, and gunnery sergeants, Charles “Chuck” Frazer, 20; Carl L. Johnson, 20; Charles E. Gretz, 19 and Alessandro S. “Pan” Panarese, 20. All of the men were single except Eselgroth, Lucas, [and Miller].

From the tail turret, Panarese called his sighting on 215-B, as required, by intercom to Eselgroth for entry in 491’s logbook. A moment later Iron Duke was slammed upward by three bursts of flak. Duke felt the controls go slack in his hands and knew they could not remain in formation. Nearly all of the ships left rudder had been torn away, a wing’s aileron vanished, holes appeared in the fuselage and severed control cables dangled in the waist compartment. Duke made a jagged right turn, then ordered Miller to salvo the bomb load. Their twelve highly explosive cylinders were screaming earthward immediately, and soon began bursting in the village of Meckbach. Mrs. Katherine Kraft was the only fatality when five homes were hit. Above, the pilots struggled to keep Iron Duke airborne while asking Eselgroth for a heading to the nearest friendly forces lines. Duke did not want to risk going back toward heavy flak areas along the Rhine with limited control and at such a low altitude.

The Iron Duke maneuvered easier minus the bombs’ weight, but it was impossible to hold a fixed heading with only the autopilot’s few cables intact. They were flying with a 30-degree yaw to the right, airspeed of 110 knots and with 20 degrees of flaps, were able to maintain 7000 feet of altitude.

Eselgroth called Duke and gave him a heading of 210 degrees. This would get them close to advancing American ground forces south of Frankfurt. Duke then ordered Eselgroth, Miller, and [nose gunner] Johnson to leave the nose section and come up to the flight deck in case they had to bail out.

The Iron Duke moved slowly on, and although the crew was on alert to jump, they felt good about reaching Allied lines before having to leave the ship. At 1315 hours, 491-I was north of Gelhausen, and Duke tried a turn southward to avoid flak batteries around Frankfurt. The response was almost nil. Lieutenant Erich Bauder, commander of a [German] railroad flak battery, saw a four-engine bomber approaching and posted his crew. They had four 128mm and two 20mm guns mounted on a flatcar at Mulheim station, near Offenbach. Bauder even felt pangs of pity for the men inside the aircraft, for he knew, at their speed and altitude, they could not escape from his deadly radar-controlled firepower.

A ranging shot exploded in front of and below the aircraft. Then three quick bursts put the Liberator out of control, and it began descending immediately. Eruptions under the left wing had ripped out a five-foot section of fuselage and started a hot fire in the waist compartment. Duke unwittingly agreed with Bauder—Iron Duke could not escape. He ordered his crew to bail out while some measure of control remained.

Over Gelnhausen, Miller was first to leave, followed by Garcia and Eselgroth. Then Johnson, Panarese, and Frazer jumped just before Iron Duke suddenly dropped its nose and fell earthward. Duke juggled the auto-pilot while centrifugal force glued him and Monroe to their seats. Gretz was still in the top turret. Slowly the plane responded to his coaxing and leveled off at 3000 feet. Duke sent Gretz out the open bomb bay and Monroe right behind him as puffs of flak continued to burst around Iron Duke. Gretz looked up and saw chutes, and then watched as 491-I made a sharp turn south-eastward.

People on the ground had heard the flak barrage begin, and they started to watch the course of events. Many saw chutes blossoming and a burning bomber bobbing its nose while slowly losing altitude. Southeast of Frankfurt, near the village of Hainhausen, Iron Duke dropped one wing just before it struck the ground, nosed over on her back and exploded with an intense rumble.

Painting: Mike Bailey

Meanwhile, Miller descended into an open field near Mulheim and was quickly captured by civilian police. He was marched through the streets toward Offenbach police headquarters. On the way, civilians began calling out threats and abuse to Miller, then attacked. Once, he went down and a hobnail boot opened a gash on his forehead. Finally the police were able to move him away from the mob and reached safety at headquarters. One of the officers said in broken English, “The people are enraged over killings by American aircraft.”

Garcia slammed into a large storage building with glass skylights on its roof. He was bleeding profusely when police came and moved him to an adjacent field.

As Eselgroth descended he saw that his spot would be a home’s backyard with several brick walk-ways and a picket fence. Fortunately he hit on soft earth. He untied his brogan shoes (these are better for walking than low quarter shoes worn inside the fur-lined flying boots) from his chute harness and held one in each hand. Looking up, Eselgroth saw a gate and next to it a sergeant scaling the fence and wearing the SS uniform complete with drawn Luger.

[Sergeant] Max Ruchel approached to within ten feet and asked Eselgroth, “Have you a pistol?” Eselgroth responded, “No pistol”, while raising his hands still holding a shoe in each. The sergeant walked around Eselgroth, frisked him and called out for someone in the house to unlock the gate. Mrs. Juliane Kaiser, the property owner, unlocked her gate and Ruchel motioned Eselgroth to go out. “I should at least give that flier a cup of coffee,” Mrs. Kaiser thought as he started to the gate with raised hands.

As Eselgroth started through, a group of civilians reached the gate followed by soldiers from the flak battery. The mob screamed threats and insults first, then attacked with tools and sticks. Ruchel grabbed a soldier’s rifle and clubbed several of them back, then prodded Eselgroth into running down an alley while the soldiers retained the mob.

As they walked toward the town’s center, children along the way began spitting and throwing small stones at both men. Adults poured verbal wrath upon Ruchel for protecting an enemy flier while wearing the SS uniform. Ruchel left Eselgroth with members of the flak battery crew until police arrived. Then he was marched to the railroad station and seated on its frontal cobblestone roadway.

Johnson landed about 50 yards from Eselgroth. His chute caught on the gable of a house, stranding him several feet above ground. Some distance away an old man called out in broken English, “Hands up!” while he waved a handgun. Policemen came immediately, however, and carried Johnson to a nearby rail car for safekeeping.

Panarese bailed out the camera hatch in the rear fuselage, while flak burst around Iron Duke and shrapnel pierced his shoulder. He landed midway in the rail yard with his chute draped over a boxcar, suspending him 15 feet up. He pushed the chute’s harness release, fell to the ground supine and lost his breath momentarily. By the time he could breathe again a policeman was hustling him to the railroad station.

Later a truck came to carry Panarese to Offenbach hospital for first aid on his shoulder. Two other crewmen were already aboard. Garcia (left) was very pale and continued mumbling, “Sanar…sanar,” (Spanish for cure or heal me). Miller was bleeding from a wound on his forehead. At the hospital, Miller and Panarese were treated, then presently asked to identify Garcia’s body as a member of their crew. A Dr. Wolf had given him a transfusion which had failed to save his life.

Lucas touched down with his chute tangled in an apple tree. Three forest workers were nearby and began making verbal threats. But a soldier, on leave, had seen the chute, started toward the airman and arrived simultaneously with the workers. He kept the civilians from harming Lucas until police arrived.

Frazer tumbled earthward struggling with a balky ripcord. At the last possible moment the canopy blossomed, breaking his fall. He landed in a thick, wooded area near the village of Bieber. Police and army troops searched for hours in vain, then finally gave up.

Gretz also came down in the open and to immediate capture by police. He had no encounter with civilians, and was allowed to retrieve his perpetual supply of candy bars attached to his chute harness, which he began eating promptly.

Monroe jumped and his chute opened immediately. Gretz waved from below, Monroe returned it and looked above to see Duke’s chute. Two policemen were waiting for him in a field near Bieber.

Duke landed shortly after Monroe, and policemen were in the field when he touched down. They carried Duke directly to the Bieber police station.

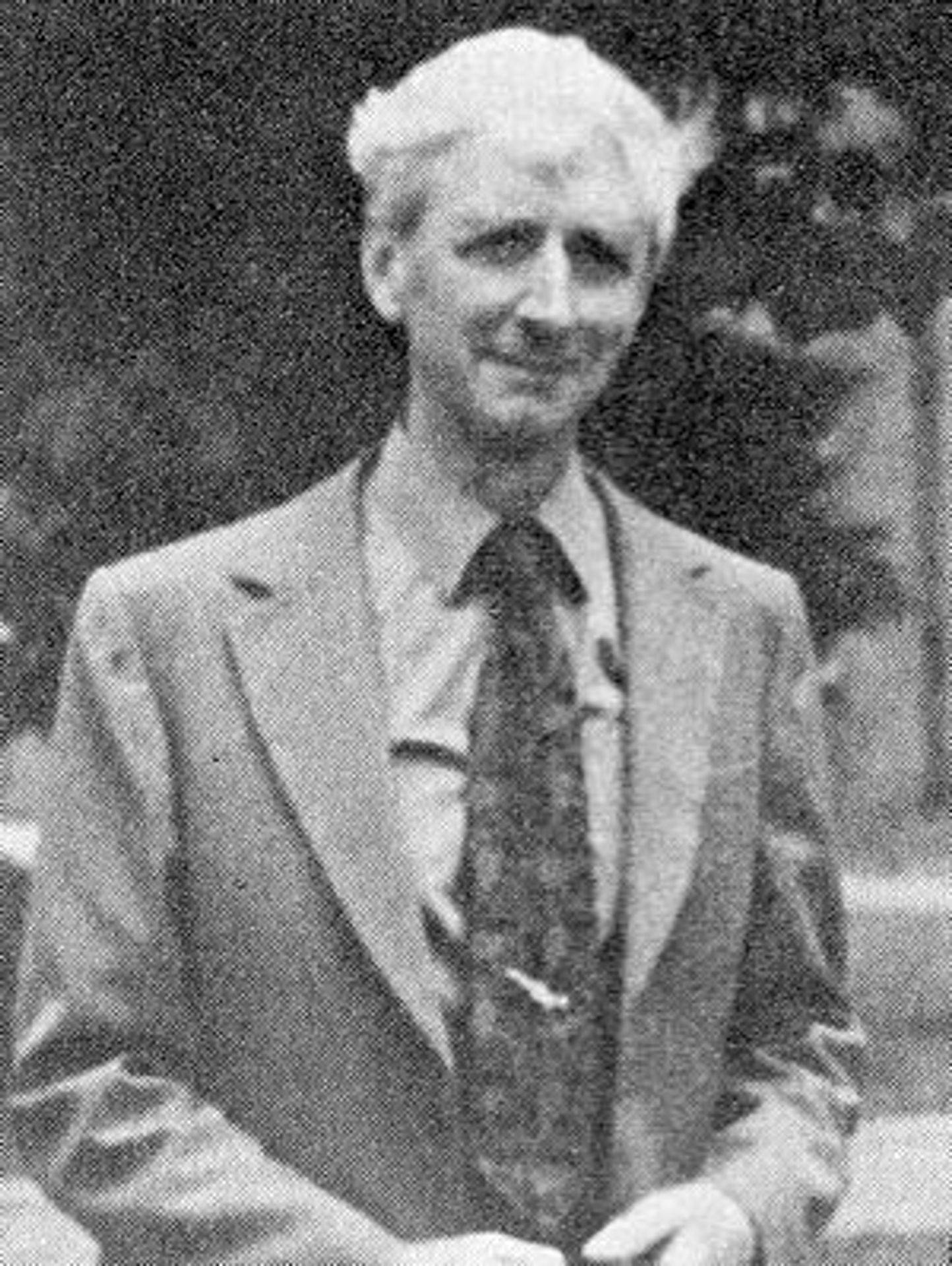

F/O Richard Eselgroth

Sgt Alessandro Panarese

Sgt Charles Gretz

Sgt Albert Lucas

Sgt Carl Johnson

By 1515 hours, Eslegroth, Miller, Panarese, Gretz, Lucas, and Johnson had been captured and were seated on the cobblestone roadway at Mulheim railroad station. Miller and Panarese whispered to the others that Garcia had died. A crowd of both curious and hostile quickly gathered. Verbal threats and abusive language (in English) flowed from the people. The Americans became apprehensive about their safety until soldiers from the flak battery were posted to keep the civilians at bay.

One man, dressed totally in black, singled out Eselgroth for foul verbiage after one of the guards read the names aloud from their brown jackets. He kept ranting for several minutes. But a hush settled over the crowd when Lieutenant Bauder came from the battery and talked with the crewmen for a moment, asking whether everyone was alright. Pointing to Eselgroth’s nameplate he said, “Deutsche?” and he nodded affirmatively. “Why do you return to bomb the fatherland?” [Eselgroth responded,] “I’m an American, Lieutenant…we’re at war.”

The afternoon wore on, and the airmen began quietly surmising that they were being held here awaiting the arrival of Duke, Monroe, and Frazer. Gratification seeped in among the fliers over a good possibility that those not here had escaped captivity. The guards apparently spoke little or no English, for they would not answer simple questions from their prisoners. Using sign language, Eselgroth asked whether the quadruple-barreled 20mm gun had been the one that shot them down. One guard finally smiled and pointed to the 128mm guns.

At twilight, when the others had not arrived, the six crewmen were placed aboard a wood-burning truck and carried to a large jail near Hanau. Here they were lodged in separate cells overnight and the next morning were given black bread and coffee—their first food and drink in 24 hours. Next they boarded a train back to Frankfurt and spent the entire day in a bomb shelter beneath the railroad station.

In the evening, another train carried the airmen northward to Oberursel where a Lieutenant “Hausman” questioned them. He pretended to be writing a book called “Name, Rank and Serial Number,” based on prisoner’s information, to be published after the war. The lieutenant threatened to have them shot as spies unless they gave him technical facts about their unit. All said the same thing. They had been in England less than two months when shot down, and actually knew little or none of the data he wanted. Later, he showed each one the contents of a thick folder left on his desk during interrogation. “Hausman” already had more details on the 458th Bombardment Group than the six men combined knew.

Iron Duke’s crew was separated for a short time, but eventually all of them were interned in Stalag Luft III near Sagan, about 100 miles southeast of Berlin. After American ground forces crossed the Rhine in early March 1945, the war’s outcome became definite. When April arrived, POWs were force-marched southward from their barbed wire compounds.

En route to their final imprisonment, circumstances changed drastically for all Allied prisoners. Red Cross parcels (food and personal items) were plentiful. The guards (middle-aged men of the Luftwaffe) were suspected of “going along with the crowd.” And it appeared that the journey was more burdensome for them than their prisoners. The POWs helped some of the older men carry packs, and at times, even weapons. Frequently they said, “Deutschland ist kaput.” No one considered trying to escape with the war all but over. A POW asked one guard for his helmet as a souvenir. The guard replied, “Wait a few days and you can have the uniform to go with it.” Another prisoner offered a guard, in jest, ten cigarettes for his rifle.

Moosburg was a depot for incoming Red Cross parcels from Switzerland, and on 14 April the Iron Duke’s crew reached this huge POW center. All prisoners were treated well here and simply waited for “the day.” On 29 April a single P-51 buzzed the compounds, and shortly after machine gun fire rattled as a Sherman tank of the 14th Armored (Liberators) Division crushed the main gate beneath its treads. “Liberated” cars, trucks, cycles, and a few horses carried the jubilant former POWs about the town in frenzied activities.

Soon there was a truck ride to a captured airfield, next to France by C-47 and on to the States (via Southampton, England) by ship. During their days of captivity the Iron Duke crew inquired about their missing members from every possible source, but not a hint of them was heard. Meanwhile, in America, families of all ten men had exchanged bits and pieces of information while conducting a campaign to learn the fates of Duke, Monroe, Frazer, and Garcia—six others had been reported to be POWs through the Red Cross.

When 1946 arrived, hope again arose for the four crew members as teams of special troops began combing Germany and the occupied countries for thousands of missing personnel. In Oxford, Mississippi, Mrs. Homer Duke received a letter from General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower stating that her oldest son’s death in a plane crash in 1943 over Australia had been confirmed. He also expressed his regret that “Billy” Duke was still Missing in Action.

On 6 March 1946, the graves of Garcia, Frazer, Monroe, and Duke were discovered in a small cemetery in Muhlheim. Their remains were exhumed and sent to an Allied cemetery at St. Avold, France the next day. After family notifications, Graves Registration officials conducted thorough examinations on the bodies of recovered Allied personnel. In the case of Frazer, Monroe, and Duke, it was obvious they had not died from wounds consistent with the known facts—statements from fellow crew members established that they had all reached the ground safely except Garcia.

War crimes investigators entered into the inquiry, and a more intensive investigation began. Meanwhile, [the bodies of] Duke, Monroe, and Frazer were returned for burial in their hometowns. Garcia’s mother elected to leave her son at St. Avold.

The Superior Orders War Crimes Case (The United Sates of America v. Jurgen Stroop et al) was held in Dachau, Germany from 10 January – 21 March 1947, in which twenty-two individuals were tried under a general charge of Violation of the Laws of War—in the main, criminal acts against Allied airmen. Lt. General Jurgen Stroop was accused of receiving and transmitting orders from the likes of Heinrich Himmler and Ernst Kaltenbrunner down to local police levels to shoot any flier parachuting from a damaged aircraft over Germany. He was also charged with following the principles of Joseph Goebbels and Martin Bormann to incite the German people to lynch airmen. And police were instructed not to interfere as civilians assaulted the defenseless fliers.

Jurgen Stroop eliminated the final Jewish resistance at the Warsaw Ghetto in the spring of 1943. His activities there, well documented in a report to Berlin, moved the Polish government to seek his extradition for trial on crimes against the Polish people. He was sent back to Warsaw, convicted and executed on 6 May 1952. His compatriots, all those known to have been associated with the deaths of Monroe, Duke, and Frazer were prosecuted. Trial testimony revealed the last hours of three of the Iron Duke’s crew.

Lt. Monroe was captured by two Bieber policemen. En route to Offenbach police headquarters an air raid warning sounded, and the three men went to a shelter that also housed a fire station. Inside, the assistant police director, Josef Kiwitt, fire chief, Paul Nahrgang, and two of his assistants, Bernard Fay and Phillip Hammann were present. They began a whispered conversation, during which Kiwitt ordered Monroe shot. Access to the shelter was limited to two doors. Monroe was provoked into leaving the area, after allegedly striking Fay, then ran toward the street. Fay began yelling, “Halt” while firing his pistol into the air. Meanwhile, Hammann went out the other door carrying a rifle. He fired three shots at Monroe, killing him instantly, “while trying to escape”—still wearing his heavy flying suit and fur-lined boots. The body was then taken to Offenbach police headquarters.

Lt. Duke was captured near Bieber and carried to the police station. He asked for and was given something to drink, then permitted to smoke. Shortly, Hans Eichel, Offenbach police director, and Josef Kitwitt arrived. They strongly rebuked those present for allowing Duke such privileges. More conversation followed and Duke was sent to an army post in Offenbach to be held as a POW. On the way there, Sgt. Herman Moller, Bieber police, shot Duke “while trying to escape”—in his heavy flying suit and fur-lined boots. His body was also taken to Offenbach Headquarters.

Insufficient material evidence prevented a trial being held in Sgt. Frazer’s death. However, records told of his plight. He hid well until Sunday, 25 February, but became weak and cold from lack of food and water. Church bells began ringing in the early morning and Frazer moved toward them. He saw a Catholic church in Bieber and went there, hiding in a shed at the rear of it. Finally Frazer approached Chaplain Mathias Felder for assistance, but some of the parishioners were in the church after Mass due to an air raid warning and saw the American flier.

The people started a heated squabble about Frazer, and the chaplain had no choice but to turn him over to the police (because of alienation between the Church and Nazi Party). On the way to Bieber’s police station, Felder told Frazer of Duke’s and Monroe’s fate and expressed the hope that his would be different. Stenographer Liesel Blummer was at home when police Lieutenant Kurt Anfall (fictitious name to protect innocent family members) came and ordered her to headquarters to record an interrogation of the captured airman. She had heard him express his regret for not being present on Thursday when the others were captured. A Luftwaffe officer was at the station as she arrived, but Anfall refused to release Frazer to him for transfer to an army post. Instead, he began accusing the padre of giving aid and comfort to a prisoner.

The lieutenant failed in his assertions, however, and Chaplain Felder was allowed to return to his church. Anfall ordered one Lieutenant Blum to bring a motorcycle to the nearby sports field, stating he would go no farther with the American. Anfall marched Frazer to the field, shot him, got on his motorcycle and rode away. The body lay there all day, and was carried to Offenbach headquarters that evening.

The decisions of the Dachau court were that Hans Eichel, director of Offenbach police, was responsible for the death of Lt. Monroe. His aide, Captain Josef Kiwitt, was responsible for Lt. Duke’s death. Both denied the charges unequivocally. However, they were convicted for their atrocity. On 15 October, Kiwitt was hanged, and on 3 December 1948 Eichel paid for his crime in a like manner.

Paul Nahrgang was sentenced to five years in prison for the Monroe case. Bernard Fay received the same sentence. Both were paroled early. Phillip Hammann received a fifteen year term and died in prison of natural causes on 30 July 1947. William Albrecht, Bieber police chief, was also charged with the shooting of Duke and received a death sentence, but he was granted clemency with a fifteen-year prison term. He was paroled on 9 December 1953. Bieber police sergeant Herman Moller was charged with actually shooting Duke. His sentence was death, but he was also granted clemency with a fifteen-year term. Moller was paroled 23 September 1954.

Shortly before American ground forces reached the Offenbach area, as they battled northward, Kurt Anfall disappeared. He has not been heard of again, and all efforts to trace his whereabouts were unsuccessful.

Roger Freeman

Hubert Blasi

Eugen Lux

Dick Eselgroth was on a tour of England in 1971 when he met Roger A. Freeman. Roger, a noted Eighth Air Force historian and author, had just received a letter from Hubert Blasi in which he translated a story written by a fellow German historian, Eugen Lux, on the events of the Iron Duke and crew. Eselgroth began planning a return trip to Offenbach for more details about his aircraft and the deceased crewmen.

Eugen Lux had phenomenal success in further research of the incident of 22 February 1945. He located records and eyewitnesses to most of the events that day twenty-eight years before. In 1973, Eselgroth went to Mrs. Juliane Kaiser’s home for a very belated cup of coffee. The now Dr. Erich Bauder was a congenial host—this time! He recalled vividly his musings of pity for the men in the Liberator for he thought some, perhaps all,would die when the radar-controlled flak guns began firing. Neither man held any residual animosity, they mutually agreed that war is as it is for both sides.

Eselgroth waited anxiously but unsuccessfully to meet Max Ruchel again. He felt a personal thanks to the former SS sergeant who saved him from the civilian mob was long past due. Seemingly, Max would be the most difficult to locate, as Lux had so little to go on and with thousands of possibilities.

Eselgroth, Lux, Blasi, and Werner Girbig, a historian on crashed German aircraft, went to the site of Iron Duke’s tomb. Using Girbig’s metal detector, they dug up twenty-five pounds of debris such as switches, ammunition, hoses and the like. Also, farmers had regularly plowed up various fragments and tossed them into a clump of trees nearby. This spot now became a delightful treasure pool for gathered historians. At least part of the Iron Duke would finally rotate back to the States.

Gene Lux eventually located Max Ruchel (left) near his own home. During the war he had been visiting his fiancée, and since returned to marry and live in Offenbach. On 18 June 1974 Lux’s letter was dispatched by air to Eselgroth in California. It arrived 26 June. However, Eselgroth underwent surgery in April, and postoperative complications ended his life two days before [the letter arrived].

There can never be an amicable conclusion to the story of the Iron Duke, nor for some of its peers. But in sentiments of Eugen Lux, who also endured war, political fanaticism eclipsed reason and humanity… henceforth, may abiding hope temper mankind’s decisions when required.

The experiences of this story are based on a collection of official documents and accounts of persons involved or observers that were compiled by Richard M. Eselgroth, Sr., 1945-1974. Many of these were obtained through the enthusiastic and tireless efforts of Eugen Lux, translated from German to English by Hubert Blasi and accommodation by Roger A. Freeman. For simplicity, the events appeared sequentially without regard to the information’s origin.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The 458th Bombardment Group II, George A. Reynolds, 1979.

Missing Air Crew Report No. 12675, HQ Army Air Forces for Aircraft No. 44-10491, 1 March 1945.

The Air Raids Against Offenbach-on-the-Main 1939-1945, Offenbach Historical Society, Eugen Lux, 1971.

National Archives and Records Service Pamphlet, Trial Record of War Criminals, 1981.

Combat Chronology 1941-1945, Office of Air Force History, HQ USAF, 1973.

2Lt Richard M. Eselgroth

3 September 1945

SUBJECT: Casualty Information No. 4819

TO: 1st Lt. Charles B. Glasaw, Jr. Casualty Branch, AG,

Munitions Building Rm 4408, Washington 25 D.C.

1. The following is a true account of the action in which the four missing members of the crew of B-24 #491 Liberator, of the 754 Squadron, 458 Group, 96th wing, 2nd Division, 8th Air Corps [sic] took part on 22 February 1945.

2. The mission in question was a low altitude mission against a rail center at Reinburg. The original briefing was for Peine, Germany but in a last minute navigation briefing, it was changed to Reinberg. We were briefed to bomb in two groups. There were approximately 28 planes in the group using the same I.P., 14 going to one target and 14 to another. On the way to the I.P. at approximately Eisenach, Germany, we were hit by enemy flak. The ship was crippled and we left formation. As near as I can determine from statements by members of the crew, our right aileron and left rudder had been shot away.

The pilot gave the order to salvo the bombs, which was done immediately. I gave the pilot a heading to the nearest allied lines. He expressed difficulty in keeping the plane headed in the desired direction. The plane was flying in about a 30° list to the right and we were heading approximately 210° magnetic. In view of the fact that the ship was crippled, the bombardier attempted to open the nose wheel emergency door. The door would not open. I let the nose gunner out of his turret, and he, the bombardier and I went up on to the flight deck. The bombays [sic] were still open after salvoing the bombs and we figured it would be safer to stay on the flight deck in case we had to abandon ship.

3. We were flying at 7000 ft. with an indicated speed of 125 mph with our flaps down to maintain the altitude; we could not contact our friendly fighters; co-pilot Monroe made consistent attempts to contact our airplanes, but was unsuccessful. Two thirds of the way back to our lines, we were hit again by railroad flak batteries at the town of Gelnhausen, Germany. The first burst missed the ship and because of our slow speed and low altitude, the enemy got in approximately seven or eight hits, further damaging the plane. The radio operator in the waist at the time, said the 50 cal. Ammunition was exploding; there were several large holes in the waist. I observed the auxiliary power unit severely damaged by flak and large holes in the belly in front of the forward bomb bay. One burst hit in the vicinity of the #2 engine, very close, causing the pilot to throw his left hand over his head, at which time he gave the order to bail out. I heard the flak hit the side of the ship. The bombardier was first in line to go out the bomb bay [sic], the engineer second, nose-gunner third, and myself fourth. As of this time, none of the members of the crew forward of the bomb bay had been wounded. Later, on the ground, I was told that Sgt. Panarese was hit by flak as he went through the escape hatch in the waist. He was hit in the left shoulder and was treated by German medics on the ground.

4. I landed in the backyard of a house some 500 yards from the flak guns that had shot us down. I was immediately taken into custody by a German Sergeant of the flak unit, who took me to the railroad station where the flak guns were located. On the way we were attacked by civilians and severely beaten. Arriving at the railroad station, I was told by the Germans that one of my comrades had died and that one chute had not opened. Because of my lack of knowledge of the language, I could not determine whether they were talking of the same member of the crew or two different members of the crew. Looking around the station, I observed Sgt. Panarese, Sgt. Lucas, Sgt. Johnson, Sgt, Gretz, and Flight Officer Miller, who were also in the station.

5. We left our formation at approximately 1230 hours, and bailed out at about 1300 hours. At the time we were at the railroad station it was about 1330 hours. At approximately 1730 hours, a German army truck came and took us to a neighboring town, which I believe was Untersbach where we were imprisoned in the local jail, over night. While riding in the truck, I was informed by F/O Miller that he had seen Sgt. Garcia in the German First Aid Station. He said Sgt. Garcia’s right arm was almost torn from his body and he looked sickly pale from loss of blood. I was later informed by Sgt, Panarese that he had gone to a Germany cemetery with the body of Sgt. Garcia and was asked to identify it by the Germans, which he did.

6. No word from any source was heard by us of the three other missing members of the crew. We assumed they had evaded capture and were on their way back to our lines.

7. The next morning we were taken form the jail at Untersbach and put on a train via Frankfort to Oberusal. During my entire period of imprisonment in Germany, whenever I came in contact with other prisoners shot down in the same vicinity, I inquired about the three missing members of our crew, but at no time did I receive information regarding them. While a prisoner of war, I was with the other five surviving members of the crew, and at no time did they receive any information. In view of the fact that we were all very much concerned as to the fate of the three other members, we were constantly inquiring of fellow prisoners for information, but up to this time of writing, I have received no word concerning the members of the crew mentioned in your letter of 24 July 1945.

Signed

Richard M. Eselgroth

F/O AC. T-132898

Iron Duke Crew Escape Photos

War Crimes Investigation – 1947

Albert E Miller

Questioned by Lt Col Ross Barr

May 23, 1947

Q. State the circumstances surrounding the loss of your aircraft in the vicinity of Muhlheim, Germany on or about 22 February 1945.

A. Maybe you had better ask me some questions on that. I could probably give you a better idea.

Q. Was your plane damaged by ground fire of fighter craft?

A. Ground fire. There wasn’t any fighter craft.

Q. What type of plane was it?

A. B-24.

Q. Did the plane explode while in air or did it remain intact?

A. Not to my knowledge. It was still flying when I left the ship. Now long it stayed intact, I don’t know. It was very definitely damaged. We were hit over Insbrach, Germany first – it might be Insbrook – couple of spellings in it. It was our turning point where we were letting down through an overcast – just as we broke out the barrage hit us and at that time all of our control cables in the bomb-bay were cut, the tail was damaged and the right wing was damaged, so we left formation. The radio was knocked out, that is, our radio to the group. We left formation there and lost about 1000 feet altitude. The plane in front [Szarko] blew up – disintegrated. The right wing folded up on another ship in front of us, and he went down. The pilot was flying strictly by engines then. He didn’t have any other control. We were trying to steer between Frankfort and Koblenz to get back to France and I never did know exactly what the location was. I was navigating that day but had given my map to the navigator for pilotage. He went up between the pilot and co-pilot while I helped the engineer transfer gasoline from the right wing tank to the left wing tank. Our right wing was damaged and we were losing gas. We were hit again over a small town. I never verified the name of that town as I did not have the map at that time. We met another barrage there. Heavy [anti]aircraft on flat [rail] cars hit us. We were indicating about 125 air speed at about 8500 feet indicated altitude and the plane was nosing down and coming up – in other words, we were pretty near stall speed. We had salvoed our bombs to get rid of all excessive weight so we could keep in the air. At that time I was helping transfer the fuel We got two or three heavy barrages, then a report that the tail gunner was hit. About the third or fourth barrage the pilot said, “Get to hell out of here.” So I didn’t wait – I bailed out and tried to get the engineer to go, but he got cold feet and got the next barrage. I looked off in the distance and saw the plane still flying as I was coming down.

Q. Were any crew members killed in the plane or so injured that they could not bail out?

A. The only one I know about that was injured was the tail gunner. I saw him on the ground. Of course, he didn’t bail out when I did. He was Alessandro Panarese, Serial No. 11122931. The pilot was getting prepared to bail out and whether he was hit, I don’t know. I couldn’t see from where I was.

Q. Who was the pilot?

A. 2nd Lt. William A. Duke

Q. In what order did the crew bail out?

A. That, I don’t know, because I was the first one out.

Q. Do you know for a fact that 2nd Lt. William A. Duke, 2nd Lt. Archibald B. Monroe, Jr., and Sgt. Charles Frazer, Jr., cleared the plane and landed safely?

A. That I do not know. I never saw them after I bailed out. I never did know what happened to them. W e got no word through German interrogation what had happened to them.

Q. When did you last see Sergeant Baldmore Garcia?

A. It was on the ground. It was at what appeared to be an old garage, and his right arm at the elbow for about 6” was profusely bleeding. I tried to get to my parachute to get some morphine for him, but they wouldn’t let me. They wanted information as to whether he was a crew member of mine or not. They left me stand there until he bled to death. He lost a lot of blood. They let him die there on the floor.

Q. Do you know how Sergeant Garcia received the wounds?

A. Not definitely. But it was a pretty shattered wound. I do know that when the upper gunner bailed out he said the cat-walk was gone from flak.

Q. You say Sgt. Garcia bled to death?

A. Yes. That is the only cut I saw – on his right arm. He was very pale from loss of blood – he was still bleeding profusely.

Q. Can you name or describe any person or persons who may have been responsible for letting him bleed to death?

A. No.

Q. Can you give the names of any crew members who would know more about this?

A. No. To my knowledge, I was the only one who saw him.

Q. By whom were you captured – civilians or troops?

A. Troops. It was the land army that captured me.

Q. Can you state exactly where you were captured?

A. No.

Q. Were you mistreated in any way by your captors?

A. Yes.

Q. Exactly what did they do to you?

A. After I hit the ground a land army soldier picked me up and was joined by two more, making three guards, and civilians gathered around. We started through the town and walked about three or four blocks when the civilians pushed the guards away and started after me and hitting me with something – I don’t know what it was. They got me on the ground – then somebody kicked me in the side of the head. Next thing I knew I was being pretty severely beaten, and I pushed myself up, took a swing at one of them, hit him, and jumped in between two guards. They drew their guns and the civilians cleared away.

Q. For identification purposes can you name or give a good physical description of the person or persons responsible for mistreating you?

A. Only one. The one I definitely remember was, from all indications, the Mayor of the city. He was stockily built – very stockily built – mustache, dark hair, weighed around 185 to 190 pounds, I would say. I say I don’t know for sure, but I thought he was the mayor.

Q. About what age was this individual?

A. I would say in his early 40’s.

Q. Were you brought together with some of the other crew members upon capture?

A. At first I was taken to the jail where I met the upper gunner, Charles Gretz. We were asked a few questions and were stripped down for weapons, etc, and were left in a very unsanitary basement – I suppose it was a cell in the jail. From there they marched us up to the railroad depot where we saw my navigator – who was Richard Eselgroth; also Albert Lucas, Carl Johnson and Alessandro Panarese.

Q. Had the other crew members been mistreated?

A. Not to my knowledge at that time. They had separated us to keep us from talking, and while we were waiting there for a truck to pick us up the upper gunner, Charles Gretz, was in a box car by himself. A brown shirt started an uprising and they all wanted to hang us, or course. He broke through the guard and, with another fellow, jumped in the boxcar, grabbed a board for a weapon and severely beat Gretz. Then the guards, after a period of 5 or 6 minutes, casually walked over and broke it up.

Q. Can you describe the person or persons responsible for the mistreatment of Gretz?

A. No, I Can’t.

Q. Did you witness any other incidents of mistreatment?

A. No.

Q. Have you anything further to add concerning the treatment you and the other crew members received that would be of value to this case?

A. No, that is about all I know that would be of value.

Q. Do you have anything further to add?

A. No.

Signed

ALBERT E. MILLER

1Lt James L. Frazer

Christopher E. Frazer, nephew of Sgt Charles Frazer, Jr, sent the following information:

Losing Charles tore a hole in my father’s family; a wound that never healed. In 1952, my father, Edward Frazer, was posted in Germany; he used that opportunity to investigate the fate of the crew and was shown the gallows where some of those convicted of the crimes were hanged. His notes confirm details in the magazine’s article. His brother, James, flew a B-26 in the 9AF, 17BG, 432BS in the ETO, completing 23 combat missions. After the war, he stayed there more than a year, looking for Charles who was still listed as MIA. A photo was sent to me by my cousin Valerie (Frazer) Schutz, showing her father, my uncle James, saluting the grave of his brother Charles somewhere in France. He brought Charles home to San Antonio. He is buried at the Ft. Sam Houston National Cemetery.

Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery

San Antonio, Texas

Section S – Grave 45