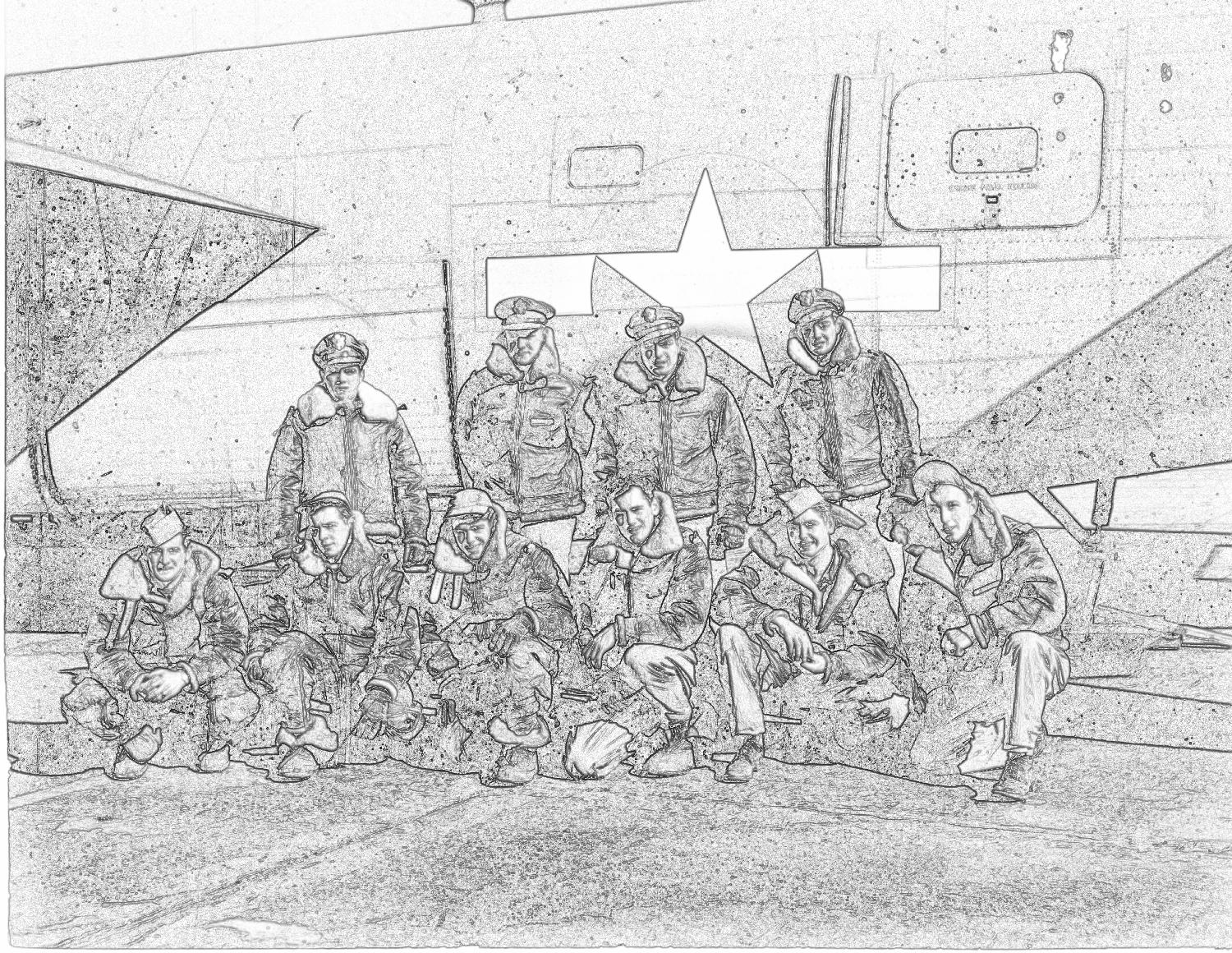

Curland Crew – Assigned 753rd Squadron – August 15, 1944

Crew Photo Needed

Shot Down – October 30, 1944 – MACR 10166

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Crew Position | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2Lt | William H Curland | 0760589 | Pilot | 30-Oct-44 | KIA | Ardennes American Cemetery |

| 2Lt | Theodore Pratt, Jr | 0767637 | Co-pilot | 30-Oct-44 | POW | Stalag Luft III |

| F/O | Grover M Long | T2599 | Navigator | 30-Oct-44 | KIA | Ardennes American Cemetery |

| 1Lt | James L Lawler | 0740705 | Bombardier | 13-Feb-45 | UNK | Trsfr to 752nd Sqdn |

| S/Sgt | Harold H Lane | 13074856 | Radio Operator | 30-Oct-44 | POW | Stalag Luft IV |

| S/Sgt | James C Butler | 34664373 | Flight Engineer | 30-Oct-44 | KIA | Cumberland County, NC |

| Sgt | William S M Crum | 37622541 | Aerial Gunner | 03-Oct-44 | DNB | Hit by landing P-47 while on bicycle |

| Sgt | James F Chism | 37537596 | Ball Turret Gunner | 30-Oct-44 | POW | Stalag Luft IV |

| Sgt | Vernon L Dunekack | 17127649 | Waist Gunner | 30-Oct-44 | POW | Stalag Luft III |

| Sgt | Victor C Drahos | 35913669 | Tail Turret Gunner | 30-Oct-44 | KIA | Ardennes American Cemetery |

William Curland and crew arrived at Horsham St Faith on August 15, 1944 and were assigned to the 753rd Squadron.

The crew’s first mission came on August 25, 1944, a day that the Group flew two missions. Curland went out on the afternoon raid to bomb a synthetic ammonia and benzol plant at Terte, Belgium. According to operational reports for that day, flak was heavy before the group reached the target and three aircraft were forced to turn for home. The aircraft Curland was flying, a B-24J named S.O.L., was forced to “…jettison bombs, due to a major gas leak in main tanks, requiring gas tank change, caused by flak before target.” Their second mission seven days later was an AZON mission. While they flew an AZON ship, Lassie Come Home, it is not known if bombardier, Grover Long, had any official training in dropping these guided bombs.

The month of September saw the 458th suspend combat operations to take part in ferrying gasoline to the Continent for Patton’s Third Army. Curland and crew flew five Truckin’ Missions, apparently without mishap.

The Group resumed combat missions in October, but before the crew’s third mission tragedy would strike. On October 2, 1944, Sgt Linwood Yarbrough, a 755th Squadron crew chief, recalled, “Our planes were marshaled for takeoff on the taxi strips, and we had a P-47 out on a weather check. On his landing, some soldier rode a bike across the runway and the P-47 hit him. Not a good sight.” That “soldier” was Sgt William S.M. Crum, one of the crew’s gunners. The cause of his death is recorded in his IDPF as, “decapitated by left landing wheel of P-47 while plane was landing.” He was buried in Cambridge the next day. He was brought home and interred in Union Cemetery, Mexico, Missouri in July 1948.

Between October 9th to the 22nd, Curland flew five missions, one of which on October 17th, was an abortive attempt in a B-24J named Table Stuff. According to the debriefing report, the crew “…jettisoned [their] bombs, the pilot reported excessive vibration, high oil pressure, high oil temperature and excessive smoking of #3 engine. Inspection revealed internal failure of engine. Necessitates engine change.”

On their eighth and final mission the crew flew a 458th original ship, a B-24J named Bomb-Ah-Dear. Apparently, no one saw their ship leave the formation, and the reason for their loss is not known for certain, but flak is the most likely cause. S/Sgt John K. McCain, a gunner from the crew of Lt William P. McCarthy, took the place of Sgt Crum and ended up as a POW in Stalag Luft 4. Lt James Lawler, the crew’s navigator, was not on this mission. It is believed that he had been removed from the crew and was undergoing training as a lead navigator. He was transferred to the 755th [Lead] Squadron in November 1944. On October 30th, F/O Grover Long was acting as navigator, going by a notation in the Missing Air Crew Report, “[He] attended Gp Navigation School and flew on mission as a Navigator.”

————————-

MACR 10166

A/C 431 probably left formation in the vicinity of Hamburg, but no definite information extracted by interrogation [of crews].

T/Sgt Harold Lane

Lt. Curland remained at the controls of the plane to allow the crew to bail out. Before he had a chance to leave the controls, the tail assembly of the plane broke off at the camera hatch, thereby losing all control of the ship and, I assume, was trapped inside the plane. [F/O Long was] in the Navigator’s compartment in nose of plane. Due to the loss of the tail assembly, the plane was uncontrollable and when the plane went into the dive, Mr. Long was trapped in the nose of the plane. [I] told Butler to come out of the turret and prepare to bail out.

Sgt James F. Chism

McCain was first man in the tail section to bail out. He bailed out in the vicinity of Luneberg. Dunekack was the second man to bail out, he also got out in the vicinity of Luneberg. I was the third and last man to get out of the waist section. I landed near Luneberg. Due to the fact that I was riding in the back section of the plane I never seen these four members [those killed] after we left the ground and started on the mission.

Sgt Vernon Dunekack

Plane was in a dive. Lt Curland gave the bail out order. He was at the controls. [Since] the plane was in a dive and broke in [two] when I left it, after which it was probably not possible for him to bail out. The Germans told us he crashed with the plane and was killed. The last communication I heard from [Drahos] he asked if the pilot had bailed out.

Missions

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25-Aug-44 | TERTRE | 119 | 1 | 44-40066 | Y | J4 | 4 | S.O.L. | GAS LEAK MAIN TANKS FLAK |

| 01-Sep-44 | RAVENSTEIN, HOLLAND | AZ14 | 2 | 44-40283 | I | J4 | 4 | LASSIE COME HOME | |

| 18-Sep-44 | HORSHAM to CLASTRES | TR02 | -- | 41-28785 | B | T1 | NOT 458TH SHIP | ON LOAN FOR TRUCKIN' 44BG | |

| 25-Sep-44 | HORSHAM to LILLE | TR08-1 | -- | 42-110063 | B | T2 | NOT 458TH SHIP - HETHEL | 1ST FLIGHT | |

| 27-Sep-44 | HORSHAM to LILLE | TR10 | -- | 42-28739 | D | T4 | NOT 458TH SHIP - HETHEL | TRUCKIN' MISSION | |

| 28-Sep-44 | HORSHAM to LILLE | TR11 | -- | 42-95001 | Z | 44BG | T8 | TS TESSIE | TRUCKIN' MISSION |

| 30-Sep-44 | HORSHAM to LILLE | TR13 | -- | 42-110063 | B | T10 | NOT 458TH SHIP - HETHEL | TRUCKIN' MISSION | |

| 09-Oct-44 | KOBLENZ | 131 | 3 | 44-40134 | R | J4 | 23 | UNKNOWN 039 | |

| 15-Oct-44 | MONHEIM | 134 | 4 | 44-40134 | R | J4 | 25 | UNKNOWN 039 | |

| 17-Oct-44 | COLOGNE | 135 | ABT | 44-40134 | R | J4 | -- | UNKNOWN 039 | ABORT #3 ENG |

| 19-Oct-44 | MAINZ | 136 | 5 | 44-40285 | H | J4 | 38 | TABLE STUFF | |

| 22-Oct-44 | HAMM | 137 | 6 | 44-40285 | H | J4 | 39 | TABLE STUFF | |

| 30-Oct-44 | HARBURG | 139 | FTR | 42-100431 | B | J4 | 41 | BOMB-AH-DEAR | SHOT DOWN - FLAK |

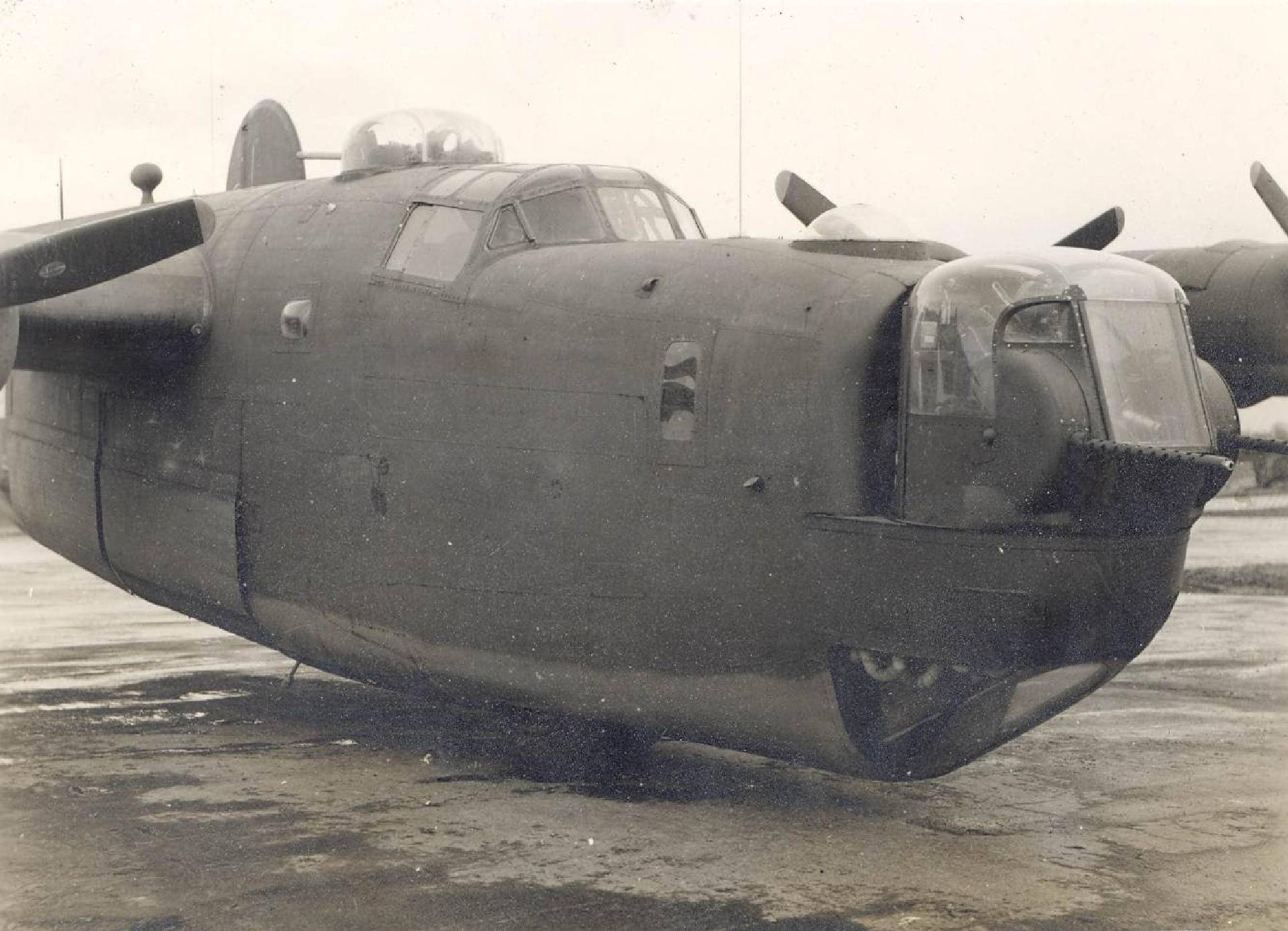

B-24JAZ-100-CO 42-100431 J4 B Bomb-Ah-Dear

This was an original Group aircraft, having flown her first combat mission on the March 6, 1944 raid on Berlin, although things did not start out well for this aircraft (see accident report below). Bomb-Ah-Dear was flown by several crews, but the crew of Wilfred Tooman in the 753rd Squadron called her “their ship” – taking her on 16 trips over occupied Europe and Germany.

This ship was able to give the Group 40 combat missions, including 7 AZON trips before succumbing to flak on October 30, 1944.

Shown above on Horsham’s taxi way and right with an unidentified Sgt

DESCRIPTION OF ACCIDENT

The pilot [Capt. Ellwood T Claggett] received orders from Group Operations to ferry aircraft B-24J #2100431 to Watton for modification. En route to the take-off position, the pilot taxied off of the perimeter strip in the soft ground with the right main landing gear. At this point, the pilot tried to bring the aircraft onto the perimeter strip by the use of throttles. The resulting shearing action caused the nose wheel main leg strut to break causing the collapse of the nose wheel.

It was also discovered in later investigations, that a flaw existed in the tube fork of the nose gear assembly. An Unsatisfactory Report (Form 54) was submitted by the Sub-Depot concerning this defect.

The pilot and failure of material were responsible for the accident. It is recommended that hereafter, when any airplane at this station taxi’s off of either the runway or the perimeter strip, that the engines be stopped and the airplane towed out by a tug.

This mishap occurred on February 10, 1944 as the 458th was gearing up to begin combat operations.

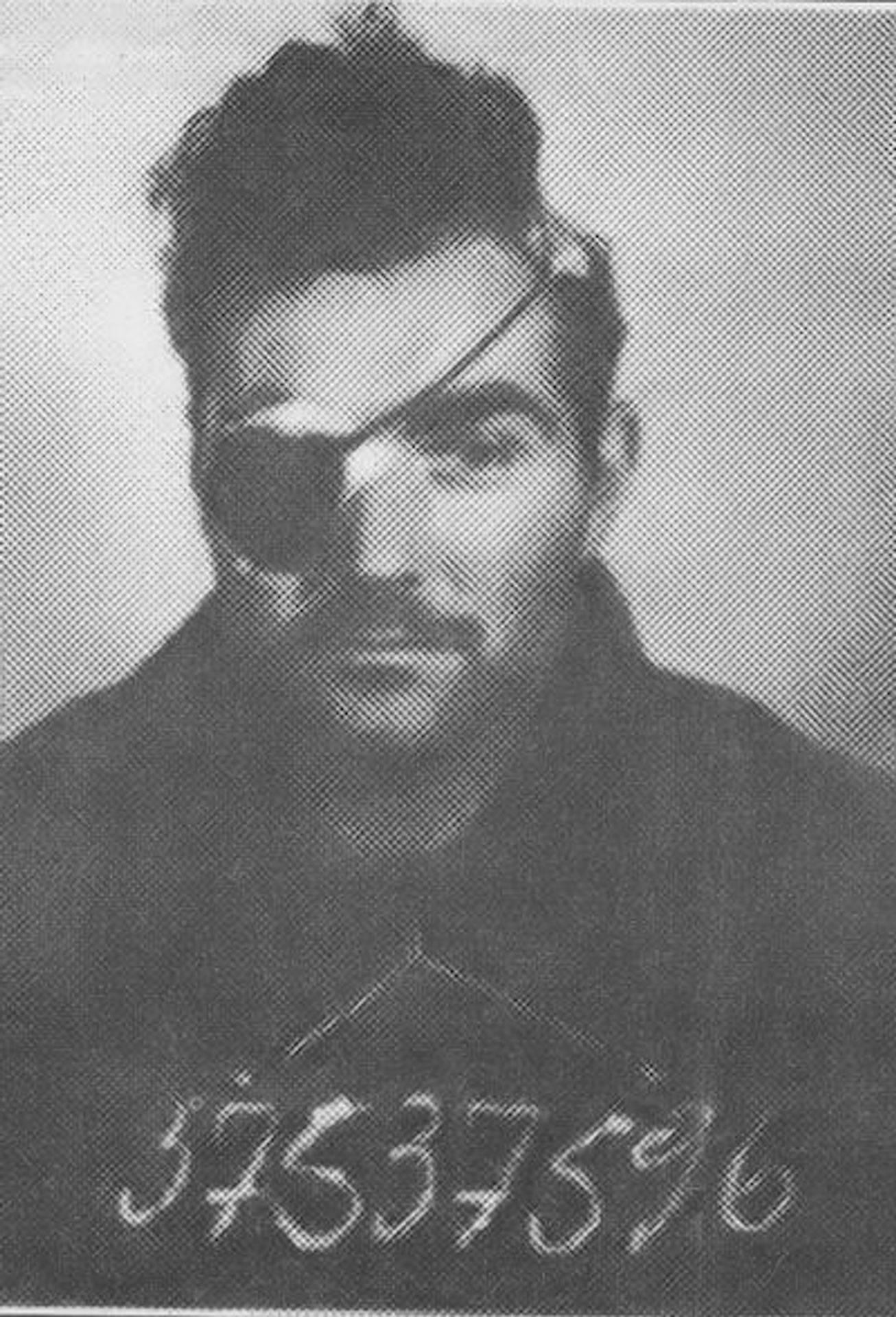

Sgt James F Chism

Jim Chism will never forget the seventh mission he flew as a gunner for the Army Air Corps. That’s when the young staff sergeant and his crew were shot down as their B-24 flew over Germany Oct. 30, 1944, the day after his 25th birthday.

“We were going up, flying around 27,000 feet,” Chism recalled recently. “A bomb run was 30,000 feet, and we were going up that high. We got hit on the No. 2 engine. It blew up and it caught on fire. “We were going to leave our formation and about that time, we got a direct hit. That blew us up and we nosed around. The front broke off; the tail broke off.” He was the fifth of the crew to get out, the last to get out alive. The other four men rode the plane down and couldn’t get out.

The five who parachuted landed miles apart. Chism landed in a little German town, where they’d let the children out of school. “The little kids were the ones who’d watch the parachutes come down and they’d follow them and tell the German soldiers where you were at,” he said.

Jim Chism will never forget the seventh mission he flew as a gunner for the Army Air Corps. That’s when the young staff sergeant and his crew were shot down as their B-24 flew over Germany Oct. 30, 1944, the day after his 25th birthday.

“We were going up, flying around 27,000 feet,” Chism recalled recently. “A bomb run was 30,000 feet, and we were going up that high. We got hit on the No. 2 engine. It blew up and it caught on fire. “We were going to leave our formation and about that time, we got a direct hit. That blew us up and we nosed around. The front broke off; the tail broke off.” He was the fifth of the crew to get out, the last to get out alive. The other four men rode the plane down and couldn’t get out.

The five who parachuted landed miles apart. Chism landed in a little German town, where they’d let the children out of school. “The little kids were the ones who’d watch the parachutes come down and they’d follow them and tell the German soldiers where you were at,” he said.

He remembers being interrogated often during the first 15 days. But just as vividly, Chism recalls a German captain who finally pulled out a black three-ring binder and said to him, “You’re not going to tell us anything, so let me tell you something.”

“He gave me all my history,” Chism relates. “He told me where I went to gunnery school, where my pilots went to school. He told me how many gallons of gasoline we’d left England with the day I got shot down, where we were headed, how many bombs we’d carried and everything.”

The German officer dismissed him, but then said, “Oh, by the way. One other thing I’d like to tell you. You guys weren’t feeling too good the day you were shot down, were you?”

Chism answered noncommittally, recalling the birthday he’d celebrated with the crew the night before. “He said, ‘You and your crew all went to town and got drunk. I thought you’d be feeling pretty bad,’ ” he said, adding, ‘I’d heard about their espionage system, but I didn’t think it was that good.”

Chism was moved many times as the Germans split up their prisoners, typically when Russian or American troops came close. During the constant movement, he had no idea whether he’d ever again see his wife, Catherine, waiting back in Leavenworth. For six weeks, she knew only that he was missing in action, until the Germans notified the military he was a prisoner of war. While the men were no longer pulled into interrogation rooms, the questions didn’t stop.

“They’d talk to you, you know, try to get you to tell them information,” he said. “They were pretty mean, especially during the Battle of the Bulge in December. They got real mean, because they thought they were winning the war.”

Chism and the other POWs had no way of knowing how the war was progressing until new prisoners were brought in. During that time, not many troops were flying. The Germans fed the prisoners little, if anything. Chism, like most of the men, lost a lot of weight – 56 pounds in six months. But their cruelty took other tacks as well.

“They’d beat you, hit you, sic the dogs (German shepherds) on you,” he said. “When they’d march you through the town, all the German civilians would come out and hit you, and knock you down. You had to lie there because you couldn’t get up, because they’d sic the dogs on you. You were afraid to move. “You just laid there until they told you that you could get up.”

Stalag Luft I, the last camp to which Chism was moved and which housed only the Army Air Corps was in the town of Barth, overlooking the Baltic Sea. The prisoners suspected liberation might be near because they could hear the guns coming closer and closer. They knew it would be only a matter of time before something happened.

“The way we knew they were getting close is that the main guards we had took off,” Chism said. “They brought in what they called the ‘old people’s army,’ the old farmers and others to man the guard towers.”

What he described as a “wild group of Russians” ultimately freed them “We were hoping they’d bring in something to eat,” Chism said. “Well, they didn’t bring it in, but they went in the farming community and brought in a lot of stuff for us, cattle and hogs. They told us to butcher them, and there they were. “We got pretty sick that night.”

Within a week to 10 days, they were flown to France, where they stayed about a month. Chism was never again on active duty. Instead, he spent the next year in military hospitals at San Antonio; Lincoln, Neb.; Clinton, Iowa; and Springfield, Mo. During that time, doctors tried to determine if his back would benefit from an operation.

Given a choice between fused vertebrae from an operation he knew would have limited his movement, Chism chose to live with the pain in exchange for the mobility. He’s not sorry he made that choice, despite the pain over the years that has now turned into what has been diagnosed as “traumatic arthritis with nerve root involvement,” settling in his legs and feet.

But that hasn’t kept him from being active. When he returned to Leavenworth, Chism went back to his job at Gould Battery Factory, where he worked until 1960. He and his wife, Catherine, built a home the next year, in 1947, where they lived until her death this summer. From 1960 to 1981, Chism worked at the Eisenhower VA Medical Center, for the state of Kansas and the Veterans of Foreign Wars as a veteran’s service representative.

In 1988, Chism decided to start a POW chapter in Leavenworth, since many area POWs were members in Kansas City and Topeka. He is still commander of the chapter, which he describes as a “real good group of people who sort of have a bond together.”

These days, he tells his story to school children, among others. But Peggy, one of his two daughters, said he never talked about his experiences when she was growing up. But now Chism is devoted to making sure people remember POWs.

“Sometimes they forget,” he said. “We’ve got to jog their memory a little bit.”

The Leavenworth Times, Veterans Day 1999 by Connie Parish

James Chism’s Timeline from being shot down to arriving home

Shot down 10-30-44 over Luneberg, Germany

Left Luftwaffe Base at Luneberg 10-31-44

Arrived at Dulag at Oberussel, Germany 11-1-44

Luft Dulag Luft 11-9-44

Arrived at Transit Camp at Wetzlar, Germany 11-9-44

Left Wetzlar 11-13-44

Arrived at Stalag Luft 4 at Kiefhiede, Germany 11-18-44

Left Kiefhiede 1-30-45

Arrived Stalag Luft 1 Barth, Germany 2-7-45

Germans began blowing up flak school and left the camp for Americans to take over on 4-30-45

Received my first letter 4-18-45

Russians arrived 5-1-45

Yanks arrived 5-5-45

War officially ended 5-8-45

Left Barth, Germany by B-17 5-13-45

Arrived Rheims, France 5-13-45

Left Rheims by C-47 5-14-45 and arrived Le Harve, France 5-14-45 (Camp Lucky Strike)

Loaded on the boat (Admiral Butner) 6-11-45

Set sail for Norfolk, Va. 6-12-45

Arrived at Norfolk, Va. 6-20-45

Left Norfolk, Va. 6-25-45

(Materials courtesy: Peggy Chism)

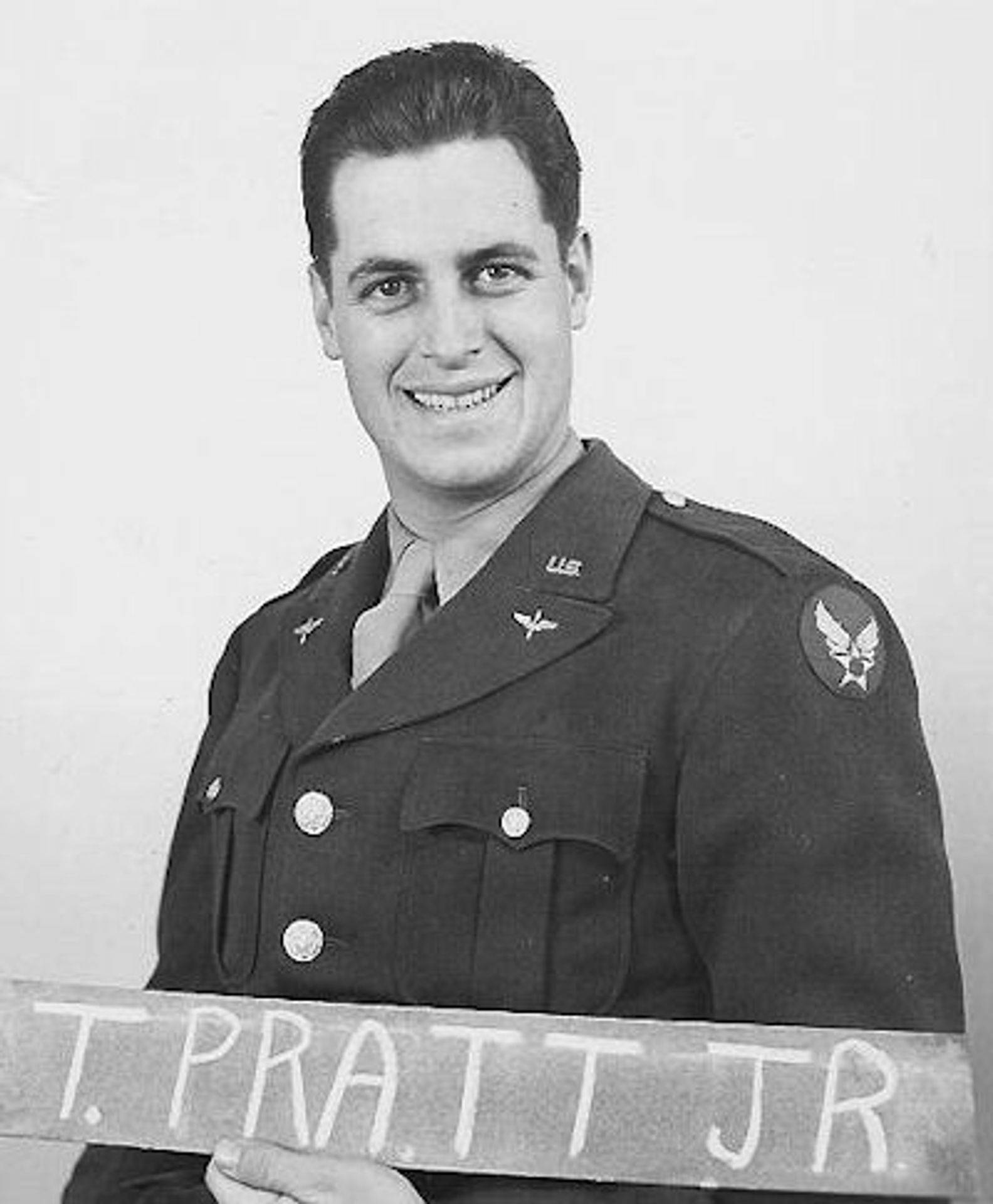

William Curland and Theodore Pratt

Bill Curland (left) and Ted Pratt were good friends who shared the first pilot duties on the crew.

After the war Pratt married Curland’s sister Bettie.

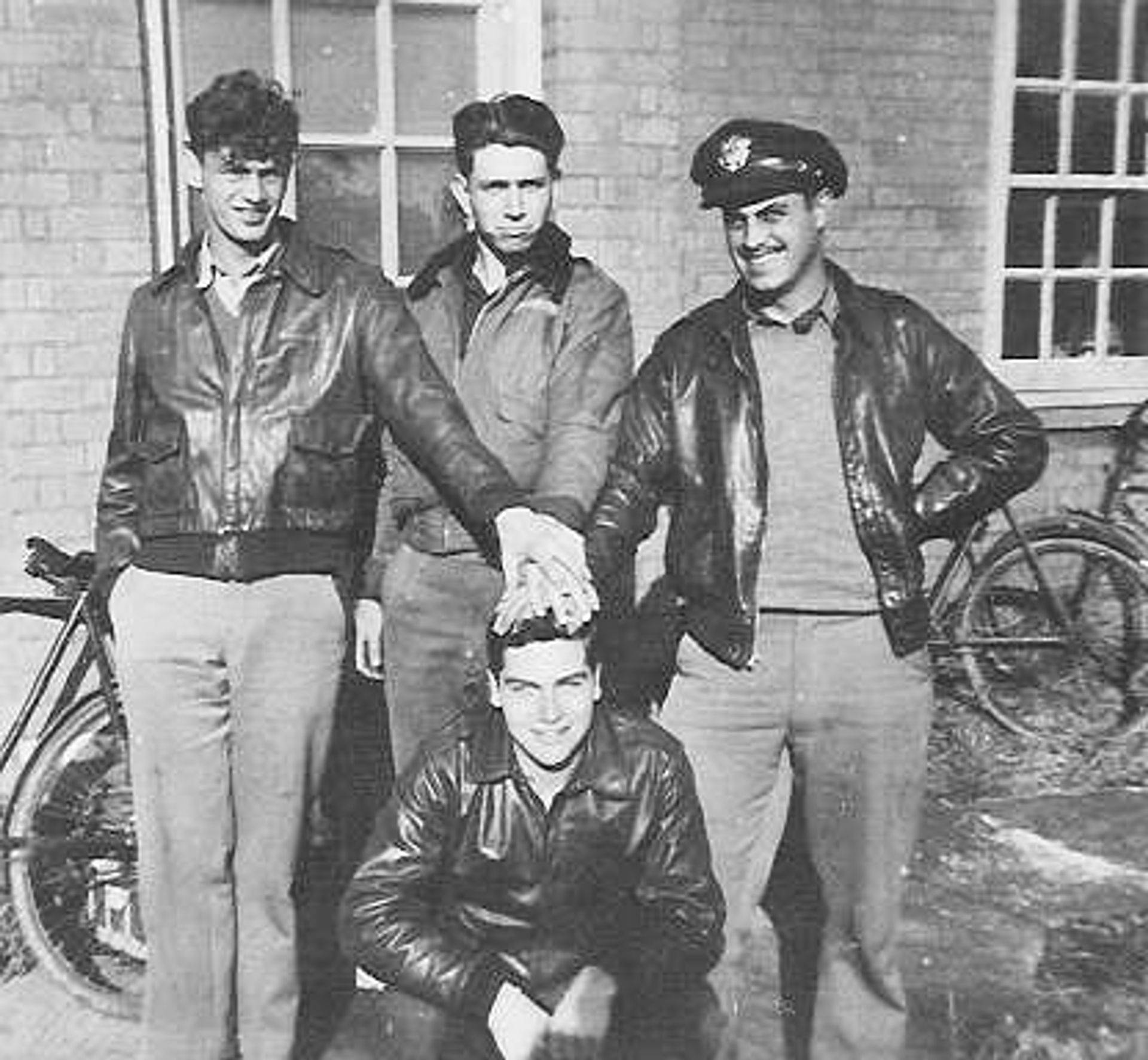

Members of Curland’s crew at Horsham St Faith.

Standing: William Curland, Grover Long, Theodore Pratt

Kneeling: Harold Lane

(Courtesy: Katherine Pratt)

Lt Theodore Pratt – Co-pilot

Both my Dad (Theodore Pratt) and Uncle (William Curland) were in the same bomber. My Dad, after he got out of the POW camp, went to talk to all the families of his crew that did not make it. He started with Bill’s [Curland’s] family, as he had already met them many, many times from previous leave’s and he was already engaged to my Mom. Mom and Dad then both went together to talk with all of the other crew families across the US.

Dad also talked about his experiences as a POW.

He said that the guards had less to eat than they did, as they received Red Cross care packages, and the [guards] were a motley collection of very young boys and old men. Many of the POWs shared some of their food with the guards.

Once someone passed him the salt shaker, but had not replaced the top and all the salt fell onto his food. He had to carefully scrape this away, so he could eat his food. (You had to know Dad, food was very important to him, so this was probably a standout moment for him personally!)

Dad said they had electric jump suits that plugged into the plane to keep them warm. When they parachuted, they did not have suitable clothes to keep warm and this was very hard, in particular for their feet.

Towards the end of the war, the Germans had them evacuate their Stalag a few times and force marched them to neighboring towns to evade re-capture by our forces. This was during the winter and their feet were very, very cold.

On one of these forced marches, the Germans left them in a manufacturing plant for the night. So Dad noticed that there were containers of grease on the ledges, and he slathered that onto his feet to try to waterproof them as best he could and then he passed these around for the others do do likewise. They used up all of the grease, which was a critical supply item and after they had marched away, and the manufacturing plant had complained, and then their German guards were very angry. It had shut down their production!

When they were freed from the Germans, they must have been sort of on their own, because Dad said that they went looking for “souvenirs”. Mind you, the last thing Dad needed was stuff… but he did “liberate” these two tiny sherry glasses, (used with some sort of alcohol), and they were hand-painted. (Nice, not museum quality, but a step-up or two from souvenir…) He showed them to me, so he had kept them safe all those years.

Emails and photo from Katherine Pratt