EM Williams Crew – Assigned 754th Squadron – August 10, 1944

Completed Tour

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Pos | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capt | Edward M Williams | 0664707 | Pilot | 19-Dec-44 | CT | Rest Home Leave |

| 1Lt | Thomas M Tarpley | 0824994 | Co-pilot | 02-Jan-45 | CT | Rest Home Leave |

| 1Lt | Burt Frauman | 0783045 | Navigtaor | 02-Jan-45 | CT | Rest Home Leave |

| 1Lt | Jerry H Ferrier | 0772955 | Bombardier | 02-Jan-45 | CT | Rest Home Leave |

| T/Sgt | Raymond Reynolds | 36644914 | Radio Operator | 02-Jan-45 | CT | Rest Home Leave |

| T/Sgt | Delbert E Hamilton | 39197187 | Flight Engineer | 02-Jan-45 | CT | Rest Home Leave |

| S/Sgt | Charles P Condon | 36767193 | Aerial Gunner | 02-Jan-45 | CT | Rest Home Leave |

| S/Sgt | Michael D Diederich | 36685011 | Aerial Gunner | 02-Jan-45 | CT | Rest Home Leave |

| S/Sgt | Henry A Hunt | 38472779 | Aerial Gunner | 02-Jan-45 | CT | Rest Home Leave |

| S/Sgt | Joseph M Lopez | 32965649 | Aerial Gunner | 02-Jan-45 | CT | Rest Home Leave |

It is assumed that most of 2Lt Edward “Murray” Williams crew completed a tour of 35 combat missions. After flying 21 missions as a first pilot, 1Lt (soon to be Captain) Williams was moved to HQ 458th Bomb Group and became a Command Pilot. 1Lt Mark H. Sherrill became the crew’s first pilot, flying ten missions between December 1944 and February 1945 when the first pilot’s job was then taken over by their co-pilot 1Lt Thomas Tarpley, who commanded the crew on the remainder of their missions.

S/Sgt Henry A. Hunt went to RCM (Radar Countermeasures) School and was reclassified in December. It is not known whether he continued with his original crew or went on to fly with lead crews where his new found skills would be put to use.

1Lt Burt Frauman, navigator, stayed with the crew throughout his tour. He very kindly supplied his list of missions which are displayed below.

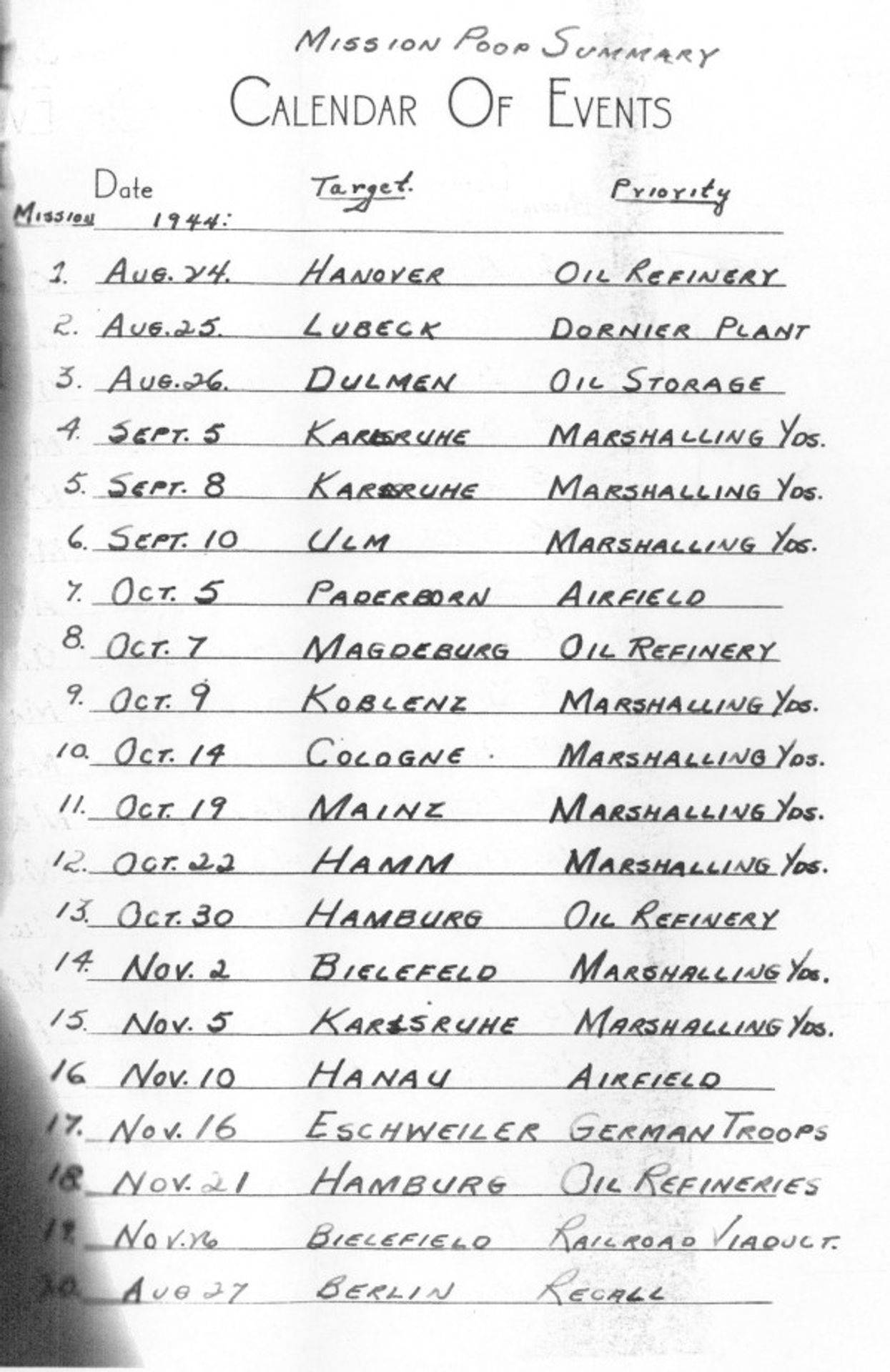

Missions – Edward Williams as 1st Pilot & Command Pilot

| Date | Target | Pilot | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Cmd Pilot | Ld | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-Aug-44 | HANNOVER | WILLIAMS, E | 117 | 1 | 42-51110 | P | Z5 | 36 | TOP O' THE MARK | |||

| 25-Aug-44 | LUBECK | WILLIAMS, E | 118 | 2 | 42-51110 | P | Z5 | 37 | TOP O' THE MARK | |||

| 26-Aug-44 | DULMEN | WILLIAMS, E | 120 | 3 | 42-51110 | P | Z5 | 38 | TOP O' THE MARK | |||

| 27-Aug-44 | FINOW | WILLIAMS, E | 121 | 4 | 44-40126 | L | Z5 | 21 | SPITTEN KITTEN / SKY TRAMP | MISSION CREDIT NOV | ||

| 01-Sep-44 | PFAFFENHOFFEN | WILLIAMS, E | ABN | -- | 42-51110 | P | Z5 | -- | TOP O' THE MARK | ABANDONED | ||

| 05-Sep-44 | KARLSRUHE | WILLIAMS, E | 122 | 5 | 42-51110 | P | Z5 | 40 | TOP O' THE MARK | |||

| 08-Sep-44 | KARLSRUHE | WILLIAMS, E | 123 | 6 | 42-95018 | J | Z5 | 43 | OLD DOC'S YACHT | |||

| 09-Sep-44 | MAINZ | WILLIAMS, E | 124 | ASSY | 41-28697 | Z | Z5 | A15 | SPOTTED APE | ASSEMBLY CREW | ||

| 10-Sep-44 | ULM M/Y | WILLIAMS, E | 125 | 7 | 42-51110 | P | Z5 | 42 | TOP O' THE MARK | |||

| 20-Sep-44 | HSF to CLASTRES | WILLIAMS, E | TR04 | -- | 42-109805 | J | 44BG | T2 | DUSTY'S DOUBLE TROUBLE | TRUCKIN' MISSION | ||

| 22-Sep-44 | HSF to CLASTRES | WILLIAMS, E | TR06 | -- | 42-109805 | J | 44BG | T3 | DUSTY'S DOUBLE TROUBLE | TRUCKIN' MISSION | ||

| 25-Sep-44 | HSF to LILLE | WILLIAMS, E | TR08-1 | -- | 41-64452 | S | T1 | NOT 458TH SHIP - HETHEL | 1ST FLIGHT | |||

| 26-Sep-44 | HSF to CLASTRES | WILLIAMS, E | TR09 | -- | 41-64452 | S | T2 | NOT 458TH SHIP - HETHEL | CLASTRES | |||

| 05-Oct-44 | PADERBORN | WILLIAMS, E | 128 | 8 | 44-40298 | E | Z5 | 1 | THE SHACK | |||

| 06-Oct-44 | WENZENDORF | WILLIAMS, E | 129 | ABT | 42-100366 | H | Z5 | -- | MIZPAH | #2 ENGINE | ||

| 07-Oct-44 | MAGDEBURG | WILLIAMS, E | 130 | 9 | 42-50640 | O | Z5 | 1 | BUGS BUNNY | |||

| 09-Oct-44 | KOBLENZ | WILLIAMS, E | 131 | 10 | 42-50640 | O | Z5 | 2 | BUGS BUNNY | |||

| 14-Oct-44 | COLOGNE | WILLIAMS, E | 133 | 11 | 42-50640 | O | Z5 | 3 | BUGS BUNNY | |||

| 15-Oct-44 | MONHEIM | WILLIAMS, E | 134 | ASSY | 41-28697 | Z | Z5 | A21 | SPOTTED APE | ASSEMBLY CREW | ||

| 19-Oct-44 | MAINZ | WILLIAMS, E | 136 | 12 | 41-29596 | R | Z5 | 61 | HELL'S ANGEL'S | |||

| 22-Oct-44 | HAMM | WILLIAMS, E | 137 | 13 | 42-50640 | O | Z5 | 4 | BUGS BUNNY | |||

| 30-Oct-44 | HARBURG | WILLIAMS, E | 139 | 14 | 42-51179 | P | Z5 | 43 | DUSTY'S DOUBLE TROUBLE | |||

| 02-Nov-44 | BIELEFELD | WILLIAMS, E | 140 | 15 | 42-50456 | D | Z5 | 8 | DOROTHY KAY SPECIAL | |||

| 05-Nov-44 | KARLSRUHE | WILLIAMS, E | 142 | 16 | 42-50640 | O | Z5 | 7 | BUGS BUNNY | |||

| 10-Nov-44 | HANAU A/F | WILLIAMS, E | 146 | 17 | 42-95183 | U | Z5 | 57 | BRINEY MARLIN | |||

| 16-Nov-44 | ESCHWEILER | WILLIAMS, E | 147 | 18 | 42-110059 | T | Z5 | 45 | UNKNOWN 056 | |||

| 21-Nov-44 | HARBURG | WILLIAMS, E | 148 | 19 | 44-40298 | E | Z5 | 13 | THE SHACK | |||

| 26-Nov-44 | BIELEFELD | WILLIAMS, E | 150 | 20 | 44-40298 | E | Z5 | 14 | THE SHACK | |||

| 30-Dec-44 | NEUWIED | BLUM | 161 | 21 | WILLIAMS, E | L3 | 42-50608 | W | J4 | 16 | FILTHY McNAUGTY | |

| 31-Dec-44 | KOBLENZ | SAUNDERS | 162 | 22 | WILLIAMS, E | D3 | 531 | V | GH | -- | NOT 458TH SHIP | |

| 02-Jan-45 | REMAGEN | BOWERS | 164 | 23 | WILLIAMS, E | L2 | 42-51939 | G | J3 | 12 | UNKNOWN 028 | |

| 10-Jan-45 | SCHONBERG | HALE | 168 | 24 | WILLIAMS, E | L2 | 42-51936 | I | J3 | 5 | UNKNOWN 027 | |

| 31-Jan-45 | BRUNSWICK | DYER | 176 | 25 | WILLIAMS, E | L3 | 44-49743 | F | J3 | 9 | EASTERN BEAST | RECALL - SORTIE |

| 08-Feb-45 | RHEINE M/Y | HATHORN | REC | -- | WILLIAMS, E | 42-95557 | H | J3 | -- | LADY PEACE | RECALL - WEATHER | |

| 09-Feb-45 | MAGDEBURG | ELLIS | 179 | 26 | WILLIAMS, E | L3 | 42-50740 | Q | J3 | 20 | OUR BURMA | |

| 23-Feb-45 | GERA-REICHENBACH | DYER | 187 | 27 | WILLIAMS, E | D1 | 42-51669 | J | J3 | 9 | UNKNOWN 026 | |

| 25-Feb-45 | SCHWABISCH-HALL | MITCHELL | 189 | 28 | WILLIAMS, E | L2 | 42-50740 | Q | J3 | 24 | OUR BURMA | |

| 27-Feb-45 | HALLE | CHIMPLES | 191 | 29 | WILLIAMS, E | D1 | 44-48837 | L | J3 | 11 | UNKNOWN 041 |

Missions – Mark Sherrill & Thomas Tarpley as Pilot

| Date | Target | Pilot | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-Dec-44 | BINGEN | SHERRILL | 154 | 1 | 42-50456 | D | Z5 | 15 | DOROTHY KAY SPECIAL | |

| 12-Dec-44 | HANAU | SHERRILL | 156 | 2 | 42-95018 | J | Z5 | 60 | OLD DOC'S YACHT | |

| 25-Dec-44 | PRONSFELD | SHERRILL | 158 | 3 | 42-50456 | D | Z5 | 19 | DOROTHY KAY SPECIAL | |

| 27-Dec-44 | NEUNKIRCHEN | SHERRILL | 159 | 4 | 42-50456 | D | Z5 | 20 | DOROTHY KAY SPECIAL | |

| 30-Dec-44 | NEUWIED | SHERRILL | 161 | 5 | 42-50456 | D | Z5 | 22 | DOROTHY KAY SPECIAL | |

| 31-Dec-44 | KOBLENZ | SHERRILL | 162 | 6 | 42-50456 | D | Z5 | 23 | DOROTHY KAY SPECIAL | |

| 14-Jan-45 | HALLENDORF | SHERRILL | 170 | 7 | 42-50456 | D | Z5 | 25 | DOROTHY KAY SPECIAL | SUB DEPOT |

| 16-Jan-45 | MAGDEBURG | SHERRILL | 171 | 8 | 44-40298 | E | Z5 | 20 | THE SHACK | |

| 03-Feb-45 | MAGDEBURG | SHERRILL | 177 | 9 | 42-50456 | D | Z5 | 29 | DOROTHY KAY SPECIAL | |

| 06-Feb-45 | MAGDEBURG | SHERRILL | 178 | 10 | 42-50456 | D | Z5 | 30 | DOROTHY KAY SPECIAL | |

| 09-Feb-45 | MAGDEBURG | SHERRILL | 179 | MSHL | -- | -- | -- | -- | MARSHALING CHIEF | |

| 17-Jan-45 | HARBURG | TARPLEY | 172 | MSHL | -- | -- | -- | -- | MARSHALING CHIEF | |

| 17-Feb-45 | ASCHAFFENBURG | TARPLEY | REC | -- | 42-110059 | T | Z5 | -- | UNKNOWN 056 | RECALL - WEATHER |

| 23-Feb-45 | GERA-REICHENBACH | TARPLEY | 187 | 1 | 42-50456 | D | Z5 | 31 | DOROTHY KAY SPECIAL | |

| 24-Feb-45 | BIELEFELD | TARPLEY | 188 | 2 | 44-10602 | P | J3 | 31 | TEN GUN DOTTIE | |

| 25-Feb-45 | SCHWABISCH-HALL | TARPLEY | 189 | MSHL | -- | -- | -- | -- | MARSHALING CHIEF | |

| 26-Feb-45 | BERLIN | TARPLEY | 190 | ABT | 42-50456 | D | Z5 | -- | DOROTHY KAY SPECIAL | #4 CYL HEAD TEMP |

| 27-Feb-45 | HALLE | TARPLEY | 191 | 3 | 42-50456 | D | Z5 | 34 | DOROTHY KAY SPECIAL | |

| 01-Mar-45 | INGOLSTADT | TARPLEY | 193 | 4 | 42-50456 | D | Z5 | 36 | DOROTHY KAY SPECIAL |

Missions flown by 1Lt Burt Frauman

Click for larger images

Anoxia – By Burt Frauman

In tight formation our 36 Liberator bombers (B-24) of the 458th Bomb Group flew the 20 miles from Norwich to the coast of northern England. We then set a course of 94 degrees for our crossing of the English Channel to the coast of Holland. Our altitude was 24,000 ft. Visibility was clear, so I was able to precisely pinpoint our position and calculate our first vital wind speed and direction. Acquiring reasonably accurate winds would have to be done again and again throughout the mission.

It was December 11, 1944 and our mission was to bomb the strategic war material being switched and loaded at the marshalling yards at Hanau. This was our crew’s 22nd combat mission. As we crossed the coast the anti-aircraft shells burst about 600 feet below us leaving their signature puffs of black oily smoke. My gut tightened as the shells were now bursting closer to our altitude. Tom, our co-pilot, spoke on the intercom, “Relax guys, I don’t think the flak is going to get any closer to us.” This welcome bit of optimistic insurance was rooted in a theory that we had generated. It appeared to us, after a number of flights, that the Germans deliberately put up a show of strength but rarely knocked our planes out of the sky when we were crossing a coast into Europe. “Into” was the operative word, for once we got deeper into Europe, or were on the way home, the attacks were more intense and more accurate.

We usually crossed the coasts at three specific locations en route to Germany, Holland, most frequently, another in Belgium, and the third in the area of Hamburg, Germany. The logic that we had developed was that the Germans deliberately allowed reasonably safe entry crossing these coasts into Europe, which gave them early knowledge of our point, or points of entry, so that they could more readily track the rest of our journey. It was a good trade-off. We welcomed any safe passage, if only the perception of it.

Two .50 caliber machine guns projected from the very front of the Liberator. They were the business end of the nose turret, a large revolvable [sic] bubble shaped clear Plexiglas assembly. Jerry, our nose gunner/bombardier, was inside honing his skills by rotating the entire turret up, down and across. He liked to make sure that the turret operated smoothly so that he could track any angle of attack by an enemy fighter.

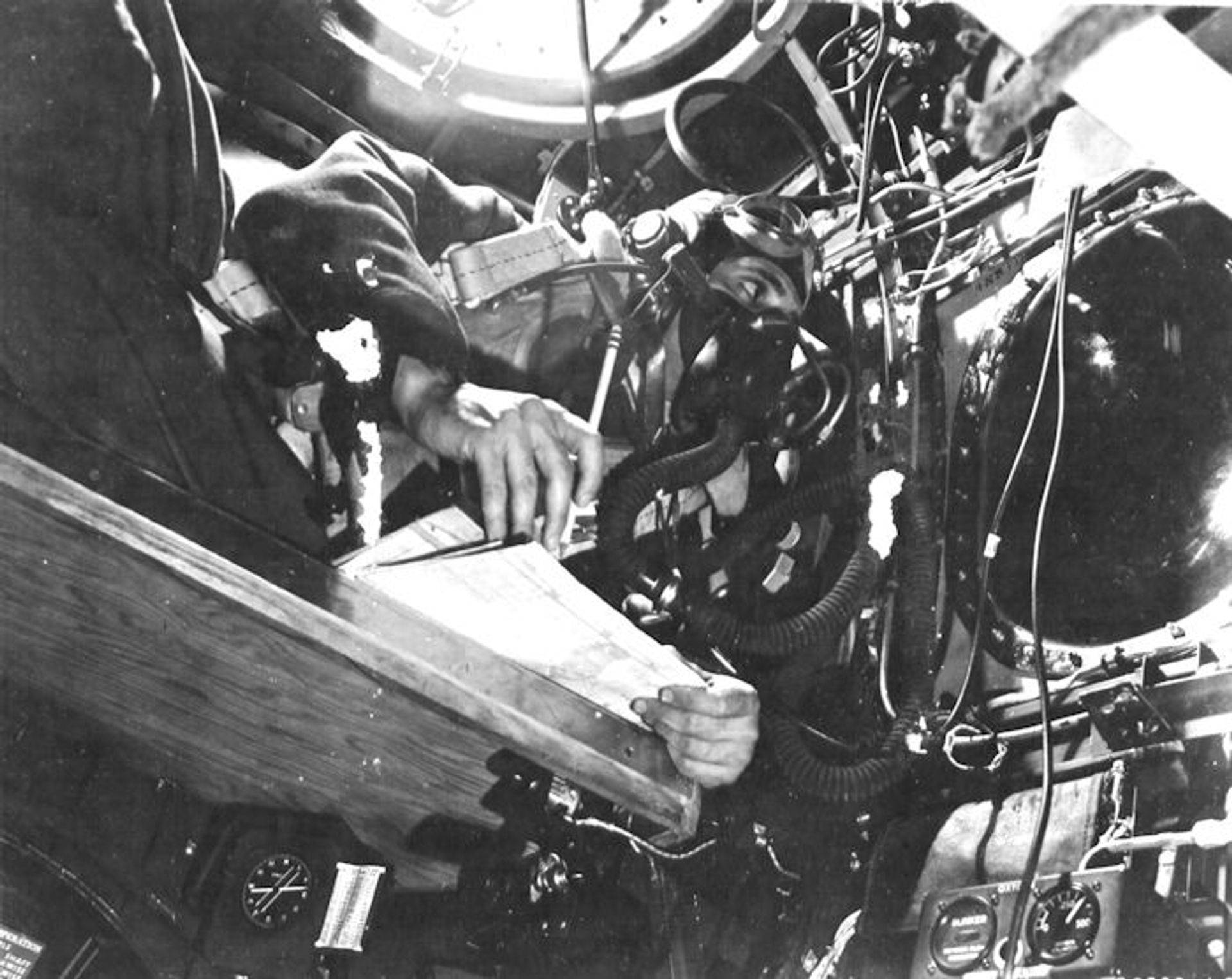

My compartment was just behind the nose turret. I stacked the flight maps that I would need on the left side of my “desk”, a deep wooden shelf the full width of the cabin. The flight instruments, such as air speed and altitude indicators, were on the bulkhead directly in front of me. I faced the rear of the plane. My viewing ports were three Plexiglas bubbles, one in the ceiling for Celestial navigation, the other two were on each side. I looked out the port on the right to check our position, and for several moments watched Holland’s Zuider Zee slowly drift behind us.

I smiled inwardly as I remembered in earlier mission when we appeared to be parked over this familiar landmark. We had been bucking a headwind of 80 knots. Our indicated air speed was 120 knots, so we were actually traveling only 40 knots relative to the ground. Of course on the way home we sped across the sky at a speed of 200 knots.

I stepped back to my desk to complete some calculations for this leg of the trip. My face was cold and wet. The moisture was the water vapor in my breath that had condensed and remained fluid under the rubber oxygen mask. I lifted my mask at the chin, and the released fluid instantly turned to ice crystals and clattered to the desk and the floor.

As we continued our mission, my hands grew painfully cold, so that I could scarcely move my fingers. My two pairs of gloves, pig skin and silk, allowed me the needed dexterity, but were not warm enough today. I was spending more and more time with one or both hands in my armpits, or my crotch. Not pretty scenes, but necessary. It was always cold at altitude, but this was extreme. I checked the temperature gauge, and shuttered. The needle was pinned at its lowest temperature “minus – 60 degrees.”

We were east of the city of Bonn on a southerly heading, as I looked down for a checkpoint to confirm our position. Bright sparks in a random pattern flashed on the ground. I recognized the scene as the firing of anti-aircraft guns, and knew that the shells were traveling about 1,000 feet each second. “Navigator to crew, flak in 20 seconds,” I announced.

458th formation flying through flak

I knew that because they were so heavy and tiring the men did not wear their flak helmets and vests all the time. My warning gave them time to put on this protective apparel. Instant clouds of black, oily smoke appeared above and below us. “Boom! Boom! Boom!” the bursting shells blasted the relative silence. Jagged chunks of steel hurled through the air. The flak helmets and vests were comforting, though we knew that there was no way to get complete protection.

The attack was brief. The chaotic scene disappeared as suddenly as it had appeared. Again we had only the steady drone of the bomber’s engines. We suffered these attacks several times on every mission. So far not a member of our crew had suffered any serious injury. We prayed that our luck would hold out.

The situation was very dangerous, and only a fool would not have been afraid. I certainly was scared, particularly during an intense attack. I managed to suppress my fears in between attacks. Danger and fear were the realities of our service, and we never discussed it. It was taboo to discuss our personal feelings. Combat was exciting, and I could not help being stimulated by the action and the danger. I was young.

We changed course and headed east. We often altered course to keep the enemy from knowing our target too much in advance. A short time later we turned southeast for the bomb run. The target was 90 seconds away. There was a 30 percent cloud cover beneath us. The bombardiers would have a visual sighting. The pilots maintained tight formation, even tighter for more concentrated and effective bomb patterns.

With sudden impact the sky again became chaotic as flak burst below us, then above us as the enemy gunners bracketed our path. I looked forward and could see the marshalling yards directly ahead of us. Again the noise of the explosions and the clouds of black, oily smoke punctuated the sky as the shells burst all around us. We were committed to a straight run for the target. I recognized the marshalling yards from the photographs that we had seen at the briefing early this morning. Bombs Away! The bombs appeared to drift back away from us as we continued on our forward path. I watched the bombs fall as the flak continued to burst at our altitude. We broke formation and our right wing dipped sharply as we made a wide sweep to the right. I looked back at the target and saw the bombs exploding on the ground, blowing up tracks and trains. We were right on target, and I would have a good intelligence debriefing report when we got back to our base. Yet we knew that these railroad yards would be operating again in less than a week.

It was likely that some personnel were injured and planes were damaged, but I did not see any of our planes go down. The formation drew together again as we headed for home.

Despite the excitement and the demands of the mission, I had not forgotten about the extreme cold. Only my feet and hands were a problem, for I wore an electrically heated suit that was just adequately effective on this mission. We were about a third of the way home, and I was making some entries in my flight log. Suddenly I felt light-headed, a giddy feeling. It was just a mild sensation, but I gasped as the terror of the potential consequences engulfed me. Anoxia? I fought panic as my mind flashed back to the past experience that ominously warned of the life-threatening danger.

In November 1943, at Selman field, LA, our class in advanced navigation was in a high altitude chamber, a reinforced concrete and steel Quonset hut. Polished hardwood benches filled the entire length of each side of the chamber. Oxygen masks hung from the wall at spaced intervals. Two husky soldiers were inside with us. One of them pulled shut the heavy metal vault door, then rotated its large brass wheel in a clockwise direction. Apparently the chamber was now tightly sealed. Both men walked back through the wide, clear aisle to their places on the narrow wall opposite the entry.

“Hello, I’m Captain Clark,” the body-less voice filled the room. The captain was outside the chamber looking in through the round porthole on the opposite wall. “Today we will take you to an altitude of 25,000 feet, precisely creating the oxygen conditions for that altitude,” he said. “How many of you are familiar with anoxic anoxia?” Several of the men raised their hands.

The captain continued, “We know that the 200 mile atmosphere above the earth compresses the air at the earth’s surface. As we go up in altitude, there is less pressure, and less oxygen in the air to breathe. Anoxic anoxia is the lack of a normal supply of oxygen to body tissues. It occurs when blood flowing through the lungs or the brain does not pick up enough oxygen. This scarcity of oxygen is present at altitudes of 10,000 to 15,000 feet and above. In this chamber, as in actual flight, you are to put on your masks at 10,000 feet, though many of you will not feel anoxic effects until you reach 15,000 feet. Oxygen is mandatory at that level and above. A person will lose consciousness when the oxygen content of the air is about one-half normal, the condition at 25,000 feet. That person must immediately be given sufficient oxygen, or he will die. Death normally occurs within minutes.”

The captain signed off with comments about relaxing until we reached the test altitude. Some minutes later he came back on the air as he announced: “We are at 25,000 feet. We need a volunteer who will remove his mask. Number 4 will you do it?” I looked around to see which of my buddies was the “volunteer”. “Oh! Oh!” I thought when I saw a few fingers pointing at me. I glanced over my right shoulder. Sure enough I was Number 4. I knew of course that this was a mandatory assignment, unless I really felt that I had to chicken out. “Captain, can we discuss this?” I questioned.

The captain chuckled, and said, “Oh sure, it’s really quite simple. We want you to remove your mask and keep it off as long as possible. However when you really sense the need for oxygen, put your mask on by yourself, then sit down. I repeat, put your mask on by yourself. The sensation that you want to look for is a slight high, like a couple of beers too many. There will be no taste or odor.”

“The two instructors in the room with you are very competent. They will help you, if any support is needed. They lost only six volunteers last month. Are you ready?”

I would like to have said, “Hell no!” Instead, I replied, “Yes sir!” the only allowable military response. I rose to my feet ready for the adventure. One of the soldiers handed me a clipboard with a pad of paper. I removed my oxygen mask, and my adrenaline spurted upward. “Print your name and serial number at the top of the page.”

“Now sign your name and add your serial number.” I did.

“Draw a 2-inch square and a circle touching the insides of the square.”

“Draw a 2-inch circle, and a square inside touching the borders.” I did, on the right side of the page.

There were a couple of other simple time-consuming questions to which I responded verbally. “Start with 100 and deduct fours”, he directed. “100, 96, 92, 88, 84, 80”, I continued the countdown until I stopped at zero.

At that point I did sense a slight high. “That’s enough”, I thought, as I reached for my mask, put it on, then sat down. I picked up my clipboard, reviewed what I had written and noticed that it was neat and orderly. I may not have set any records, but I did it on my own.

I remembered all of that so very clearly. A few moments later Captain Clark said, “You did very well Number 4. You held out a long time. Why didn’t you put on your own mask?” he said, needling me.

“What? Of course I did”, I reported.

“You sure tried, but could not manage it. You fought against the sergeants helping you! Fortunately they are a couple of tough guys and they forcibly put your mask on. They gave you a good shot of 100% oxygen to bring you back”, the captain asserted.

I shook my head in disbelief. I was dumbfounded. That couldn’t be true. I clearly remembered acting on my own. Yet 19 peers were witnesses, and several were nodding their heads in agreement with the captain.

“Look at your clipboard”, I was instructed. I picked up the clipboard. It was very neat on the top half, but the bottom half was covered with wild scrawls. It was clear evidence of mental derangement. “Do you recall subtracting fours?”, asked the captain. “Of course”, I responded.

“Well, you stopped at what would have been zero, but your tongue got hung up repeating 52-48, 52-48, 52-48.” He paused, then added: “You did extremely well, holding out as long as you did. It was just a little over a minute and a half. You demonstrated the danger of anoxia, and that when you enter in anoxic state, you fairly quickly lose rational control. You may not have detected the high as early as you thought you did. It’s subtle, but life-threatening. He paused to let this message sink in, for all of us in the chamber.

“We’re pumping the chamber to ground-level pressure. Relax and enjoy the trip”, concluded the captain.

Anoxia? Only brief moments actually passed in my reflection of that guinea pig training experience. How long would I retain rational behavior? How many seconds before I would pass out? Think! My mask had been working fine. I had been getting an adequate supply of oxygen. Instinctively I began to trace from the mask to the oxygen tank for a possible break or rupture. Quickly my hands moved down from the mask to the soft, highly flexible corrugated rubber tubing in front of my chest. Soft? No, it felt firm and rigid. It had never happened before, but apparently the bitter cold coupled with the low periods when I wasn’t moving about while trying to warm my hands, allowed the moisture in my breath to freeze and build up as ice inside the tubing – restricting the flow of oxygen.

Lt Robert O. Nixon, 755BS navigator, at his station in the nose compartment.

I crushed the tubing. It was unyielding in those first anxious moments. I squeezed harder, then I could feel it crack. I continue to crush and bend the tubing and the ice broke up more and more. “Thank God it was not yet solid with ice, there was still a core of air”, I thought.

Quickly I turned the control on the oxygen tank to 100% and inhaled deeply, extremely conscious of my mental state, or lack of it. “Turn the control back to normal in a short time, or you’ll run down the supply”, I cautioned myself.

Emergency over? I relaxed slightly. The crew! They faced the same condition. I switched on the intercom: “Navigator to crew! Emergency! Emergency! It is cold enough for ice to form inside the flexible tubing of your oxygen mask. Check it immediately. Crush out any ice! If you feel dizzy give yourself a spurt of 100% oxygen. Confirm that you are okay.”

Silence, 10-15 seconds passed. I turned my oxygen tank control to a normal level.

“Tail gunner, okay”, López reported.

“Condon, okay.”

“Diederich, okay.” I visualized the two waist gunners.

“Hunt, okay.” I was greatly relieved. Ray might have been difficult to reach in the cramped belly turret.

That took care of all the fellows to the rear of the bomb bay. Now the flight deck: the engineer, the radio operator, the co-pilot and the pilot all reported that they were okay. Just one more report and we were home free.

Silence! “Jerry, are you okay?” There was no answer. My heart sank. Were we too late? Jerry was in the nose turret, and I was the only one who could reach him. I turned the handle to unlatch the crawl through door leading to the turret. It would not turn down! It was frozen! There were no tools available. I pounded the handle with my fist. My hand hurt. The handle yielded slightly. I grabbed it and pushed down, hard. I opened the door and stood up on the ledge leading into the turret. The turret was in an extreme position, facing down toward the earth. Jerry was slumped forward. Leaning over Jerry’s back, I stretched forward to reach the pistol grip that operated the turret. I pressed the trigger and faced the pistol forward. The turret rotated upward and I stopped it when the guns were facing straight ahead. Now I could reach further in front of him. I used all my strength to crush the ice in the tubing. It yielded! With the tubing passage again open, I cranked the control to 100% oxygen. Jerry didn’t move. “Breathe damn you, breathe”, I implored him.

Using both hands I pressed his back in an attempt at some artificial respiration. Then to my great relief he shook his head a couple of times, and I felt his chest heave as he began inhaling on his own. Less than a minute later, Jerry slowly sat up. He turned to look back at me, his eyes questioning, puzzled at my presence. “Are you okay?” I asked.

“Sure”, he responded, still puzzled.

“You had passed out”, I explained. He shook his head in disbelief.

“I remember now. You were talking about the icing in the oxygen mask,” he recalled. “Thanks for getting to me.”

We always minimized using the intercom, and we were still in a combat zone, so I opted to hold off any further discussion until the mission was over. I slapped him on the back then stepped down into my chamber. The crew heard the brief exchange. Of course, they too were relieved that Jerry was no longer in danger.

“Pilot to navigator. Nice going down there Burt. You will be happy to know that I broke radio silence and warned the group to check their oxygen systems.”

“Thanks Murray”, I responded.

Nothing more was said as we all went back to our tasks. All of our planes made it safely home that day, apparently without further incident.

Later, with time for reflection, I knew that both Jerry and I and probably others in our group were alive because I had been selected to volunteer as the guinea pig in the high altitude chamber 13 months earlier. Without the personal experience I would not have been as sensitive to the danger. I was still astonished that my mind had locked onto that, “one beer too many” giddy feeling and immediately matched up the two experiences to alert me to the life-threatening danger of anoxia.

This story was submitted to the Second Air Division by Burt Frauman

S/Sgt Michael D. Diederich – Gunner

Veteran oral history interview published by the New York State Military Museum. The State of New York, the Division of Military and Naval Affairs and the New York State Military Museum are not responsible for the content, accuracy, opinions or manner of expression of the veterans whose historical interviews are presented in this video. The opinions expressed by those interviewed are theirs alone and not those of the State of New York.