Crew 68 – Assigned 755th Squadron – October 20, 1943

Shot down April 9, 1944, Easter Sunday – MACR 3838

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Crew Position | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2Lt | Byron E Logie | 0807003 | Pilot | 09-Apr-44 | EVD | E&E Report 583 |

| 2Lt | George D Reed | 0811138 | Co-pilot | 09-Apr-44 | EVD | E&E Report 584 |

| F/O | Bernard A Jacobson | T123027 | Navigator | 09-Apr-44 | WIA/POW | Unknown POW Camp |

| F/O | Walter J Kita | T1541 | Bombardier | 09-Apr-44 | POW | Unknown POW Camp |

| S/Sgt | Thomas R Murphy | 32111635 | Radio Operator | 09-Apr-44 | EVD | E&E Report 585 |

| T/Sgt | Walter E Scott | 35451477 | Flight Engineer | 09-Apr-44 | POW | Stalag 17B |

| Sgt | John H Schramm | 31254158 | Ball Turret Gunner | 09-Apr-44 | KIA | Ardennes American Cemetery |

| Sgt | Frederick E Stiles | 15334471 | Aerial Gunner | 09-Apr-44 | KIA | Buried unknown |

| Sgt | Edward W Cisek | 11115618 | Aerial Gunner | 09-Apr-44 | KIA | Buried unknown |

| S/Sgt | Sidney Sheren | 32818617 | Tail Turret Gunner | 09-Apr-44 | KIA | Buried Cemetery Svinoe |

Logie’s Crew trained with the 458th in Tonopah and flew the Southern Route to England in January 1944. They flew most of their missions in B-24H-15-FO 42-52432 J3 P that reportedly was named, Bachelor’s Paradise. Unfortunately no photographs of this plane are known to exist.

Their twelfth and last mission came on April 9, 1944 – Easter Sunday when the 458th set out to bomb an airfield at Tutow, Germany. Weather would be the deciding factor in this mission as 2nd Bombardment Division summary shows: “Low and middle cloud presented a difficult problem in the assembly. Groups encountered multi-layer clouds from 8,000 to 15,000 feet from Splasher 5 until approximately fifty miles west of the Danish peninsula, and many ships lost their formations and were forced to abandon the mission. The remaining ships formed into two composite wings with aircraft of the 2nd Combat Wing, 446th and 93rd Bomb Groups comprising one Wing, and units of the 96th Combat Wing and 445, 392nd and 44th Bomb Groups comprising the other. The Division leader, flying with the 2nd Combat Wing, made a 360° turn off the Danish coast in an attempt to reform the Division, but cloud layer and haze made visual contact difficult and the 96th Combat Wing leader did not perceive this maneuver and proceeded to the target thirty miles ahead of the 2nd Wing.“

Due to the broken formations, the groups missed their rendezvous with the fighter escort. After passing through the cloud cover over Kiel Bay at about 1110, a number of German fighters attacked the B-24 formation, Logie’s plane taking hits [see his detailed account below] and they were forced to bail out over Denmark. The plane crashed and burned in the village of Venslev. Three men were captured, and three evaded, making their way to Sweden relatively quickly. The evadees were back in England by April 26th. They were sent to London for debriefing. They were then sent back to Horsham for a short period where at least one of them (Lt Logie) gave lectures on his experiences. In May all three men were transferred to Mitchell Field, NY. On May 19, 1944, Lt Logie was interrogated by MIS-X Section and the report of his evasion, EX Report No. 327 was created.

Four of the crew were killed. One man, Sidney Sheren, jumped, but his parachute either did not open or did not have enough time to open before he hit the ground. Three of the gunners were unable to bail out and were killed when the plane struck the ground.

————————-

MACR 3838

No statements

Missions

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 05-Mar-44 | BORDEAUX/MERIGNAC | 3 | 1 | 42-52432 | P | J3 | 2 | BACHELOR'S PARADISE | |

| 06-Mar-44 | BERLIN/ERKNER | 4 | 2 | 42-52432 | P | J3 | 3 | BACHELOR'S PARADISE | |

| 08-Mar-44 | BERLIN/ERKNER | 5 | 3 | 41-28719 | Q | J3 | 4 | PADDLEFOOT | |

| 15-Mar-44 | BRUNSWICK | 7 | 4 | 42-52432 | P | J3 | 5 | BACHELOR'S PARADISE | |

| 21-Mar-44 | WATTEN, near ST. OMER | 10 | 5 | 42-52432 | P | J3 | 8 | BACHELOR'S PARADISE | |

| 23-Mar-44 | OSNABRUCK | 12 | 6 | 42-52432 | P | J3 | 10 | BACHELOR'S PARADISE | |

| 24-Mar-44 | ST. DIZIER | 13 | 7 | 41-28735 | S | J4 | 4 | UNKNOWN 005 | |

| 26-Mar-44 | BONNIERES | 14 | 8 | 42-52353 | J | Z5 | 12 | UNKNOWN 049 | |

| 27-Mar-44 | BIARRITZ | 15 | 9 | 42-52423 | -- | J3 | 6 | UNKNOWN 031 | |

| 08-Apr-44 | BRUNSWICK/WAGGUM | 17 | 10 | 41-29302 | P | 7V | 9 | NOKKISH | |

| 09-Apr-44 | TUTOW A/F | 18 | 11 | 42-52432 | P | J3 | 16 | BACHELOR'S PARADISE | FTR - BAILED OUT DENMARK |

2Lt Byron E. Logie

“As we approached the west coast of Denmark there was a high bank of clouds running north to south. We had climbed to 23,000 feet trying to go over them, but as we approached we could see they were at least 3,000 feet above us. We were then told to spread out and take up a heading of 90 degrees and hold that while flying through the clouds. When we came out on the other side we were scattered all over the sky. The German fighters were waiting for us and started to attack us before we could get back in formation. They were yellow nosed ME-109 fighters that were from Goering’s crack fighter group, protecting the German sub pens.

Two fighters attacked my plane head on and shot out both inboard engines and also most of our electrical system. The explosion was so loud I had ringing in my left ear for three days. My navigator [Jacobson] had been hit by a piece of shrapnel that had nicked the artery in his neck. The blood flew everywhere and I knew he had to get to a doctor fast or he would die. I told my bombardier [Kita] to jump with him and try to get to a doctor. I found out later that we were still over Germany. German solders picked them up as soon as they hit the ground. A doctor saw him within fifteen minutes, which saved his life.

After they jumped I told my flight engineer [Scott] to try to get to the tail of the plane to check on the men there, as we had no voice communication. He only got as far as the door, but two bombs that had not jettisoned had blocked it.

After being attacked and losing two engines my first thought was to try to make it to Sweden. It was a neutral country and we would not be prisoners of war. I was losing some altitude, but knew, as I got lower, I could stop losing altitude and make it on two engines. About that time a third German fighter attacked and shot out a third engine. I could also see a part of the rudder had been hit, but I still had control of the plane. Now I was losing altitude at from 3,000-4,000 feet per minute.

My co-pilot turned on the jump alarm. I was hoping that it was sounding in the back of the plane. I ordered everyone to jump as fast as they could. I had no way of knowing what was happening in the back of the plane. I was hoping that they had jumped. I stayed with the plane as long as I could, giving them as much time as possible.

When I got down to 2,000 feet I knew I had to jump then or die in the plane. I got out of my seat and ran to the bomb bay and jumped. As soon as I cleared the plane I pulled the ripcord and the chute opened. What a beautiful sight. I was down to around 700 feet above the ground when my chute opened. I watched my plane make a wide circle and hit the ground and explode. The plane had crashed in a small Danish village. I found out later that no one was hurt and that it had set fire to only one small shed that burned. [Photo at right: Finn Buch]

I landed going backward in a fairly high wind. I stopped the chute from dragging me and took it off. I buried my chute in a plowed field were I had landed. I looked around and saw that I had landed near a farmyard. I ran as fast as I could toward the barn. There was a stack of hay piled against the barn, so I crawled into it. I got about four feet into the stack and pushed hay back where I had crawled in. After a short time I heard the bombs explode that were in the plane.

A while later I could hear people coming toward the barn. When they got near the barn I could tell that there were two or three German soldiers and the Danish farmer. They came out to where I was hiding and stood about four or five feet from me. I could tell someone was sticking a pitchfork into the haystack, but he never got near me. I was afraid the farmer might turn me in. He was taking a very big, big chance hiding me. If they caught him the Germans would probably kill him and his family. He did not give me away although he was standing only a few feet from me and knew where I was.

I stayed in the haystack until about midnight. After I crawled out I went inside the barn and stood at the door so I could see the house. I could see three people standing around talking. Two of the men soon left. In about a half an hour I saw the farmer walking toward the barn. I then stood in the doorway so he could see me. He motioned me to follow him to the house. When we got inside he called his daughter who was about 15 years old. He said something to her and she would relay the information to me in broken English. She asked me if I was hungry. I told her I was and they fixed me some sandwiches and milk. After I ate she asked me different questions that she would relay to the others. At first she was very shy about her English, but as we talked she got much better. She told me her dad had contacted someone that would come and pick me up. At one thirty a young man came in. He told me that a pickup truck would come by in thirty minutes and we would jump on it and hide in the box. Then he would drive us to a place were I would be safe. I thanked the farmer and his wife for hiding me and for the food. I also thanked the girl and told her that her English was very good. She just smiled and thanked me.

[Four years ago I got a package from the girl that I had talked to in her father’s home. She had dug up my parachute and they had used it to make several things. She cut out a piece about three feet square and sent it to me. It is one of my most prized possessions as it had saved my life. Also the boy that had helped my co-pilot [Reed] and radio operator [Murphy] escape came to see me four years ago. Him and his wife stayed with us five days. The local TV station came out and took some pictures. They had visited the rest of my crew that was alive and the widows of my crew that were dead. He is a Danish farmer and the girl I talked to is his sister-in-law. I am now the last member of my crew still alive. Ejvind Friis Jensen, the boy who helped Reed and Murphy are good friends of ours. We send letters and email to each other all the time.]

After we jumped in the pickup truck we drove for twenty minutes, and stopped at a house in a small village. We went to the house and were met at the door by a man in his forties. He greeted me with perfect English and he told me he was a doctor who had studied medicine in California. I stayed at his place for eight days. He said it was too dangerous to travel as the Germans were looking for us. They were stopping and searching every vehicle. Later that week he told me they were going to try to move me. They wanted to get me to Copenhagen. In the afternoon an ambulance stopped and the driver came in with an ambulance uniform for me. After I got it on he told me that I would be his helper. If the Germans stopped us I was not to speak. If they talked to me he would tell them I was a mute. About dark we got into the ambulance and started out. Everything went well for the first hour then we were stopped at a German roadblock. I was scared as hell and I was hoping it didn’t show. The driver showed the guard some papers as they talked in German. In less then ten minutes they waved us through. We were stopped once more and it was about the same. I tell you, I was very nervous and I was shaking inside. We got to a good size city and went to a residential area and stopped at a nice house. We went in and a couple that had one child greeted us. I was told that he was on the police force and his twin brother was also. They were both over six feet and looked every bit the part. I stayed with them two days and then I was back in the ambulance with the same driver.

He told me that this time we were going to try to make it to Copenhagen. He said the Germans had evidently given up looking for us on the road. We had better luck this time, as we were not stopped. When we got to Copenhagen we stopped at a four-story apartment building. We walked up to the fourth floor (no elevator) and knocked on the door. A young man came to the door and let us in. There were three men that were all college students. They talked for ten minutes or so and the ambulance driver left. All three of them could speak English so it was pretty good. They told me they would be in school during the week and that I had to be very quiet as on the other three floors lived families of German soldiers. They told me that we would go out to eat and that I had to learn to keep my fork in my left hand or the Germans as well as the Danes would know I was an American. At every meal they would coach me on how the Europeans ate. To this day I still hold my fork in my left hand a lot of the time. On the fourth day we all went to the train station that had a nice cafe. They all ordered and they ordered a meal for me. We had just about finished when German soldiers came in and blocked all the doors and started to check ID’s as people left. The men told me to finish eating, and if the Germans were still there, to go to a restroom.

They said I should stay there as long as I could and then check to see if the Germans had left. They [the Danes] left and I watched them getting their ID’s checked. They all passed through without a problem. I sat at the table for about fifteen minutes more and then went to the rest room. There were three rest rooms so I would spend some time in each. I stayed about fifteen minutes in each, but it seemed like an hour. I did this three times and each time the Germans were still there. The fourth time they were gone so I waited a few minutes and walked out of the station. As I walked I wondered what I was going to do to contact someone. You may have noticed that I have called no one by name. The reason they would not tell me their names was if I got caught I would not be able to tell the Germans who was helping me. After leaving the train station I had walked three or four blocks when a cab pulled up and one of the men told me to get in. I tell you, I couldn’t have been happier to see someone in my life. I knew this had been a very close call and someone could have spotted me and turned me in. He told me he was taking me to another place that would be safer.

We drove for about thirty minutes and came to a large house that had a six foot steel gate and a fence around the yard the same [height]. The cab driver got out and talked to someone on the intercom. He got back in the cab and the gate opened and we drove in. When we got out of the cab an elderly women greeted us and invited us in. When we got inside several young couples greeted me. I was taken upstairs to a bedroom where they gave me a change of clothing. I took a bath, dressed and came downstairs. Most of the young couples could speak English and started asking me questions. The elderly lady asked me if I smoked. I told her I did and she gave me a metal box of Lucky Strikes. I had seen them before the war. Everyone had drinks and they gave me one. After awhile they started playing music on a Jukebox. Couples started to dance and soon a young lady asked me if I could dance and I told her yes. After I danced with her, every lady there asked me to dance. I had a very good time dancing and having a few drinks.

Princess Louise Practical Household School

About 2:00 a.m. everyone started to leave. They all said goodbye and told me they were glad to have met me. They also wished me luck getting to Sweden. I went to bed and didn’t get up until 9:30 the next day. When I got up no one was there except a servant and a cook. She cooked me a breakfast of pancakes, ham, eggs, toast and coffee. That was the best meal I had had since I was shot down. About noon the lady of the house returned and she had a lunch prepared. She told me her nephew, who was 16, would be over and we could play pool or cards. She also had a couple of English novels she gave me to read. The nephew and I would play pool or cards every day. We started taking walks to his home that was seven blocks away. There was a German radar site about half way to his house. There were always two or three German guards walking around the site. They would eyeball us as we walked on the other side of the street, but they never stopped us. Now I wonder what I would have done if they had stopped us. I would have probably become a prisoner of war. Now I feel it was a foolish thing to do. [This boy’s name was Frans Sidenius, in the mid-1990’s he still lived in Copenhagen. Mr.Sidenius remembered Byron Logie with these words: “My uncle sheltered many people, including a British pilot. The American I remember very well. He was a young man who wanted to see “the enemy”. So we dressed him up in civilian clothes and took him to Tivoli.”]

On the sixth day the lady of the house told me they were moving me closer to the docks. She called a cab and had the cab driver put her bike on a rack of the cab. We drove to downtown Copenhagen, which was about five miles, and stopped in front of a very nice apartment building. The cab driver took the woman’s bike off of the cab and she parked it inside when the doorman let us in. She told me she was going to ride her bike back home. I couldn’t believe it since she looked in her mid-sixties or older. We took an elevator to the second floor and went into a beautiful apartment. I was introduced to a lady who I found out was named Andersen. I was told she was a movie star and an opera singer. The elderly women left in about an hour. Her husband came home and I met him. I was told he was a writer of novels and plays. They were well known in Denmark and parts of Europe. I stayed with them only two days when they said that the Danish Resistance would be trying to get me to Sweden.

The next day I was taken by cab to a large warehouse type building near the waterfront. We went into the building and there I met several couples and children who lived there and in other parts of town. Two of the couples I had met at the large house with the steel gate were there. I was moved every day to a new location, but always ended up at the warehouse during the day. They showed me a lot of guns, some of them German 9 millimeter pistols that the German officers wore. I did not ask them how they got them. We mostly played cards and they gave me some coins so I could play poker with them. When it was my turn to deal I said, “We will play five card stud.” They told me they had never heard of the game. Anyway I taught them how to play five and seven card stud. I also helped make some pipe and gasoline bombs. While I was in Denmark the Danish Queen had a baby girl [Cecilia Bernadotte, born in Stockholm on April 9, 1944]. The Germans would not let them shoot the cannons to announce the arrival of the Royal birth so the Danes set off eighteen pipe bombs near the palace. They said they had thrown several gasoline bombs at a grenade factory and burned it to the ground.

They also fastened a steel wire loop to both ends of a strong stick. They said they could slip the wire loop over a persons head twist the stick and kill the person without a sound. That kind of put chills down my back. From that I figured out how they got the German guns so I didn’t have to ask. One day they asked me if I would like to go for a cab ride. I said sure and we drove to uptown Copenhagen. As we passed a large brick building they told me that it was the German Gestapo Headquarters. The cab stopped about three blocks past the building. They said, “Watch out the back window of the cab.” About ten minutes later there was a very loud blast that shook the cab. All I could see was smoke and fire and the whole front of the building was gone. People were running everywhere. The cab pulled out and we were gone. I was told that many Germans had been killed in the blast. The Germans arrested everyone that was near the blast. They said many Danes would be shot and some would be put in jail. I wondered if this was the thing to do, as the Germans would retaliate by killing a lot of innocent Danes.

The third day I was there an older man came to the apartment at ten in the morning. He told me I would be going to Sweden the next day. He said I should not eat or drink anything after ten that night because we would not be able to go to the bathroom for about seven hours. He said that the people I was living with would take me to the warehouse at 2:00 in the morning. The next morning we walked to a warehouse that was on the water. As we got near the warehouse we had to wait for the signal to come in. As we were entering I could see a couple of German guards walking in front of the warehouses. We entered as the guards were walking away from us. When inside, I saw sixteen or seventeen men, women and children. There was also a mother with a six-month-old baby. They were Jewish refugees who were also trying to escape the Germans. We were told we would be going to Sweden on a barge carrying empty beer cases. The barge was about thirty feet long with an open hull where the beer cases were stacked. Along the side of the beer cases and the side of the barge there was a four-foot space. To get the women or children on the barge, they would leave one at a time.

A man would pick up two or three cases of empty beer bottles and walk to the barge, shielding the woman or child from the guard. When they got to the barge the woman or child would crawl into the space around the beer cases. Then the man would return to the warehouse to get another person. They did this until all the women and young children were on the barge. The older boys and men would pick up a couple of beer cases and go to the barge and crawl into the hiding space. I was one of the last to get on the barge. One of the Jewish boys who was about twelve and I picked up a couple of cases and walked to the barge. We put down the beer cases and crawled into our space. When the last person got in the hiding space they piled beer cases in the space where we had entered. It was still night and where we sat it was pitch black dark. We sat at the dock for another hour. The crew kept piling beer cases on the barge. The beer cases were piled about six feet above the deck. After an hour or so they started the engine. They backed up and then we felt the barge start forward and we were on our way.

The boat that took Byron Logie to Sweden

Courtesy: Finn Buch

We were only gone a few minutes when we heard a loud knock on the deck. That was the signal that a German patrol boat was signaling them to stop. Before we left we were told that we had to be absolutely quiet. If the German guards didn’t make them turn off the barge engine it wasn’t as important that we be quiet. If they made them turn off the engines then there had to be no noise at all. When they did that the Germans would listen for any noise that might reveal a hiding space. If a baby or a young child began to cry or make any noise the [parents] were told that they had to press a pillow over the child’s face. If needed they had to hold it there until the child passed out. While we sat there I could feel the boy beside me was shaking with fear. I put my arm around him and held him close. That seemed to calm him down some. I also whispered to him that we would be okay, that every thing would be all right, I didn’t know if he understood English, but I was hoping. As I sat there it dawned on me, “Here I am in the hull of this barge with sixteen or seventeen Jewish refugees. What in the hell am I doing here? What would happen if the Germans discovered us?” I could just imagine what the Germans would do; they would probably kill everyone and ask questions later. I did have my dog tags, but I was quite sure they would not ask to see them.

After about fifteen minutes we could hear the German soldiers leave the barge. The crew put the engines in gear and we were on our way to Sweden. I know everyone was praying that we wouldn’t be stopped again. We had been gone about two hours when we heard them knock again. For some reason it seemed to me everyone including the young children were very quiet. It seemed to me everyone knew we were very close to freedom. Even the young man beside me didn’t seem to shake as much. I don’t remember shaking myself, but I am sure I did. We could hear German soldiers come aboard and we could hear them talking to the crew. We could tell the German soldiers were checking their passes and the cargo. This time they stayed a lot longer. I could feel the tension build the longer they stayed. After what seemed an hour we heard the Germans leave. Everyone breathed a sigh of relief.

Then we were on our way again and happy the Germans had let us go. I am sure everyone hoped that we would not be stopped again. The old barge engine churned away for what seemed like hours. Then, all of a sudden, we could hear the crew moving the beer cases. We saw the light of day and they told us to come out on deck. We were in Swedish waters and we had escaped the Germans. Every one was smiling and hugging each other. What a wonderful feeling that was. I am sure no one could imagine how I felt or how the others felt. As I sat on the deck, all of a sudden tears came to my eyes and I started to cry. I got up and walked behind some beer cases and sat down. I had been under so much tension for so long it just had to come out. After I stopped crying I felt much better and I guess it was what I needed to do. I learned that the young boy that sat beside me had been going to school. One evening as he came close to his home he saw Germans soldiers taking his mother and father away. It was no wonder he had been so afraid. I have often wondered if he ever saw his mother and father again. He did not speak English, but as we departed I shook his hand and we gave each other a hug. He smiled and said something. I am sure he was thanking me for helping him through this ordeal.

Well, we were in Malmo, Sweden in Swedish custody. After they finger printed me and asked a few questions they let me go. After they found out I was an American airman they shook my hand and said they were glad I got away. A short time later I was headed for Stockholm with one of the barge crew. About three days after I got to Stockholm, my radio operator [Murphy] and co-pilot [Reed] arrived. I was sure glad to see them. I had not seen or heard about any of my crew since we were shot down. I had no idea what was happening to any of them. I found out that the four men in the back of the plane had all died when the plane crashed. No one knew if they were dead or alive before the crash. At the American Air Attaché Office they told me that Jacobson, my navigator, and Kita, my bombardier were captured soon after they hit the ground. They didn’t know if Jacobson had died when I told them about his neck wound. They also didn’t know anything about my flight engineer Scott. They said he might still be trying to escape. Later I found out he was a prisoner of war.

We stayed in Stockholm for two or three weeks. The Air Attaché Office gave us our pay and also gave us money to buy civilian clothes. One thing they told us that I would never forget; they said if we saw a drunken person on the street, you could take a hundred to one odds that it was an American. That says something about our drinking laws. Most countries in Europe have no age limit for drinking. We were put up in the Continental Hotel in Stockholm. We each had a nice room and bath. We were on the third floor and could look down on one of the main streets.

We ate in the hotel dining room most of the time. All the restaurants had very good food and I am sure I gained ten pounds or more. They told us not to leave any papers or other things that might be used by the Germans. They said that the hotel workers that were loyal to the Germans would pass anything on that might be used against us. We went to movies even though they were all in Swedish. We bought watches and other things that we could not get in England. At night there were a couple of dance places we could pay per dance. I met a couple of Swedish girls that could speak good English. That sure helped pass the time. Stockholm is a beautiful city and I would often walk for a mile or so just to see the sights. Every weekend you could see trains loaded with Swedish women going up to the ski resorts. They allowed the war prisoners to get out of the prison camps and go to the ski resorts.

After three weeks they told us that we would be flying back to England by way of Scotland. About eight that night we got on a small bus that would take us to the airport. Well, I guess the driver was taking a short cut. He drove under a low underpass and wedged the top of the bus in the underpass. In about an hour a staff car picked us up and returned us to the hotel. We stayed another couple of days and then made another try. This time we made it and landed in Scotland about 1:30 in the morning. They put us up in a Scottish army barracks that was about the filthiest place I had ever been in. I am sure the sheets and bedding had not been changed for months. Thank God they flew us to England the next day.

As soon as I got back to England I called my folks in Hampden, North Dakota. My mother answered the phone and was surprised to hear from me, but they already knew that I had escaped to Sweden. My uncle Carl had read a newspaper article in a Los Angeles paper that said two of my crew and I had escaped to Sweden. They were very happy and I said I would be home in a week or so. Well, you guessed it; the Army had other plans for me. I was first flown to London for physicals and debriefings. Then I went back to my home base at Norwich, England.

I was glad to see some of my old friends that were in the original squadron. There were 180 combat crew members in the original squadron. We were all told we had to fly twenty combat missions before we would be returned to the States. When I returned to my squadron there was only 33 combat crew members of the original squadron. I don’t know how many crews had completed twenty combat missions. All the rest of the crews had been shot down or were killed in crashes when returning from raids. One of the crew [members] completed his twenty missions just after I got back. In his crew only six were members of the original crew. Of the other two crews, one had three missions to fly the other had two. In those two crews I didn’t find out how many were in the original squadron. I left before either of the other two crews finished their twenty missions. I do very much hope they made it. This doesn’t mean that the 147 seven crew members were all dead. It could be that many of the crew members were prisoners of war and others could still be hiding in the country were they were shot down. Some were killed on a bombing mission and came back in the plane. They had to be replaced by the replacement crews. You can see your odds of completing just twenty missions at that time were really high. Just before the invasion of Europe, the number of missions had been raised to thirty. By the time we invaded Europe we had air superiority so that helped a lot. When I got back they had set up meetings with combat crews at several of the air bases. I was supposed to talk to the aircrews about how to hide from the Germans, how to contact the underground and also answer as many questions as I could. I don’t think I was much help as the help had come to me. I didn’t have to do any of the things they wanted me to talk about.

They finally flew me back to the States about the middle of June. We landed at Washington, D.C. and I was very happy to be back in the good old U.S. of A. After more debriefings and physicals I was sent home on a thirty-day leave. It was great to be back in North Dakota and to visit with my folks and friends. When my leave was over they sent me to a convalescent hospital at Denver, Colorado. I stayed there for two months. It was nice as they had a couple of fishponds on the grounds with trout. I fished about every day after seeing the shrink for an hour. I guess I said the right thing on my first meeting, when I told him I was having dreams of blood splattering on the navigation dome and of fighters attacking my plane. I don’t think he helped much, but after a couple of years the dreams gradually stopped. When I left the hospital they returned me to full flight status and I was back flying again which was great.

I can’t end this without saying something about my crew. The B-24 that I flew had a nose turret with two fifty-caliber machine guns. It had a top turret, a tail turret and a belly turret with the same guns. It also had two flexible waist guns that could shoot out the sides of the plane. I was assigned my crew in Boise, Idaho about the last part of summer in 1943. Every member of my crew was single. I think I had the only crew in our group where everyone was single. I can’t say enough about how good my crew was. I had the best radio operator in the group. He could get me a message or a weather report in a few minutes. My engineer was also very good as well as the rest of my crew. We were always in the top ten in practice bombing. In gunnery we were the top crew most of the time. My squadron commander [Major Donald C. Jamison] once asked me if I would trade crews with him and I told him no way. If he wanted to he could have taken my crew without asking. Not a single member ever got into trouble where I had to bail him out of jail and that was more than most pilots could say. So you can see why I was very proud of them.”

2Lt George D. Reed and S/Sgt Thomas R. Murphy

E&E 584-585: 2d Lt George D REED and S/Sgt Thomas R MURPHY

Lt REED:

I was co-pilot and Sgt MURPHY radio operator in the crew of which Lt LOGIE (E&E 853) was pilot. After we were shot up by the German fighters we tried to jettison our bombs. Four of them hung up in the bomb bay; the other six release all right. As some of the men got ready to bail out they put their parachutes on the wrong way. It struck me that it would be a good thing to have practice for preparing to bail out. The inter-phone was out between the front and the rear of the ship, so we had no word from the rear after we were hit.

When the pilot rang the alarm bell the navigator and engineer jumped from the forward bomb bay. I helped the radio operator and the bombardier and followed the bombardier out at about 3500 feet. I held my parachute until I was clear of the plane; it opened with a jerk. After the pilot jumped I saw the ship turn on one wing, hit the ground, and explode. I landed in a ploughed field and was dragged a bit by my parachute. Three civilians grabbed it and collapsed it. I saw Sgt MURPHY land on the other side of a nearby house.

Sgt MURPHY

After the fighters hit us I tried to call the navigator. When I could get no answer I crawled up to the nose to get a heading from him, but his charts had blown away. The alarm bell rang, and we got ready to bail out. After I jumped I delayed opening my parachute for about five seconds. I found that having listened to lectures by a paratrooper was a great help in parachuting.

When I landed, a couple of Danes who spoke English told me where I was, pointed out where the Germans were, and showed me where to go. Lt REED and I started walking through the open fields where there was not much cover. As we were crossing a road a man bicycled up to us. We tried to get him to give us civilian clothes, but he had trouble understanding us because his English was so rusty and because we talked too rapidly. He wanted us to follow him. When we discovered that he was taking us right into a town we decided that he was not too bright. Near the town we thanked him very much and went off another direction heading for a woods several miles away.

Lt REED & Sgt MURPHY

We understood from S-2 lectures that it was all right to go walking down the roads, but so many people took notice of us, said hello, and tried to talk to us that we started off through the woods. Later it occurred to us that S-2 probably meant that it was all right to walk on roads at night, even if you were still in your flying clothes. After we had walked some distance we returned to the road. We saw a busload of people who had passed us while we were talking to the man on the bicycle. The people were all motioning for us to come over to them. We ran over to the bus, and jumped in, and sat on the floor.

We were taken to a place from which our journey was arranged. When we reached Sweden we had a story prepared that we were caught by a German soldier but managed to escape from him in the confusion when a great many people crowded around. We realized that we must have the story of being an escaped prisoner of war if we wanted to avoid being interned, but as it turned out the Swedes accepted us and never questioned us about the point. We did not have it clearly in mind that a man should ask immediately for the American Military Attaché and give no information except name, rank, and serial number until he has seen the attaché. We were asked many questions about our experiences by Swedish officials. You have to be careful to answer no questions but those of the Military Attaché.

Compiled by

D E Emerson1st Lt, AUS

Approved by W Stull Holt

Lt Col, AC

Commanding

S/Sgt Thomas R. Murphy helped out of his ‘chute

Moments after landing, Sgt Murphy is helped out of his parachute harness by Danish civilians

Photo: Jean Morris

Ejvind Friss Jensen

Yes the photo, I gave Jean Marie Morris [Murphy’s daughter], it is taken just after Thomas R. Murphy’s landing south of my home-village Hyllested Easter day April 9th 1944 a few minutes after B-24 42-52432 crashed in Venslev village. Two carpenters Joergen Rostgaard and Evald Petersen helped Murphy off his parachute. Perhaps Evald Petersen took the photo with an old box camera of Joergen Rostgaard, who is seen at the far left. The person behind is unidentified, but in front of Murphy you see owner of the farm farmer Frederik Hansen, next right could be his farm help. In front right is my school pal (with red hair and freckles) Frede Svendsen. Note his rubber boots with wooden bottoms, which we got the shoemaker to sew to the legs, as we could not buy new rubber boots during the war.

The two guys may be looking for more biking spectators rushing to the scene. Murphy placed his parachute in the road ditch here in front of the photo. Then he went across the dirt road to meet co-pilot George D. Reed landing about 60 feet north/east of his landing. I must have arrived around one minute later, when Reed came walking with his chute over his arm and Murphy was reaching for his chest pocket for a cigarette. Both chutes were placed in the ditch, and Reed tried to burn them with his lighter, but the nylon only melted and didn’t catch fire. Then the quickly gathering crowd took their knives and started to cut the chutes apart. The airmen said: OK. The nylon were used for shirts and dresses for women, and the strings were good to hang our laundry on, as we could only get cords twisted of paper, and they broke almost at once.

I knew, I had to get the two airmen away within ½ an hour, when German search patrols would show up, so I asked them to follow me further out on the road from the village The co-pilot asked at once, where they were. I replied: “Wait a little till we gets further away, so the big crowd of Danes, tearing up the chutes, so they cannot hear what we are talking about”.

Then I said, “Southwest of Zealand”. “Is it Sweden?” asked the co-pilot?” I said, “No this is Denmark.” Co-pilot:”Is Denmark a neutral country?”

“Yes”, I said, “but we are occupied by the Germans.” It shocked them a little. Co-pilot: “Where are the Germans?” I pointed north toward Slagelse (14 miles) and east Naestved (14 miles). I went on, “You must get away from here within ½ an hour, when the Germans will arrive. I would like to bring you ½ a mile east to my dad’s farm and hide you there. But if anybody here sees that and tells it to the Germans, then my dad or I will be shot, or at least they will blow up all the buildings. Anyway, don´t go out to the crash point, from where now came high flames and black smoke. The Germans will show up there first. It is better to follow the railroad going east by my home, then hide in a small pine wood, and I will come down with a basket of food.”

I went on on my bike out to the crash point, took a few parts from the plane, and went home for a delayed Easter dinner. Going down to look for the airmen, they had gone, and I hoped they would make it alright to Sweden. Next night we heard, that the local bus driver had seen them coming down in chutes. He let all his passengers out of the bus, turned around and driving down the hill along the railroad, he sounded his horn: . . . _ the Morse sign for V [Victory], which we heard everyday from BBC in London. They came running over to the bus, got in and hid on the floor. They were first hid in a cellar in a school in next town… and so their exiting tour of evasion went on through help of 21 Danes.

T.R. Murphy’s boots at the ceremony May 5, 1995 in Venslev

Celebration of 50 year anniversary Liberation of Denmark

At the memorial stone shot by danish TV. Ejvind Friis Jensen is standing left telling the story, next Joergen Rostgaard with Murphy’s boots, behind (James Cisek) a nephew of gunner Edward Cisek, his wife Candy with son Edward, Dottie Kita (widow of bombardier), Ginger Reed (widow of co-pilot) and Karl Otto Joergensen (with banner of the local National Guard)

American flight boots from World War II

Easter day April 9th 1944 515 American bomber planes from USAAF (United States Army Air Force) were flying on a bomber mission to northern Poland and Germany. They took off early in the morning from airbases in Norfolk in England. – At the arrival at the coast of Slesvig-Holsten in northern Germany they were met by a lot of clouds, and the formation had to spread out. When they finally came clear of the clouds, they were met by 6 German yellow nosed Messerschmidt 109 fighters, which shot more of them down. – Liberator B 24 no: 42-52432 from 458 Bomb Group, 755 Bomb Squadron from the base in Horsham St. Faith had two engines destroyed, and the navigator Bernard A. Jacobsen was cut in his neck by a shell splinter. The pilot Byron E. Logie decided to break out of the formation and try to reach the neutral Sweden, but the plane lost altitude, and the hydraulic system and the intercom were destroyed.

Of this reason co-pilot George D. Reed and radio operator Thomas R. Murphy had to jump on the bomb doors in order to release 4 bombs over the sea at Great Belt (between danish islands Zealand and Funen) and 3 at the fields of Lyngbygaard, a big farm 3 miles inland. Now the navigator was bleeding seriously from the wound in his neck, and the pilot asked the engineer Walter E. Scott to bail out with him, so he could get medical care. After their landing the navigator was treated by local people, and they were both hidden away in a stack of straw. Unfortunately they were found by a German search team and taken prisoners of war. Just after they bailed out the bomber was once more attacked by a single German fighter, which destroyed the third engine. Flying on only one engine the plane was going so roughly to the right, that the pilot could not keep it on a straight course, and as it was now losing more altitude, he gave the order to everybody to bail out. At 11.30 am the bomber crashed in an open space in the village Venslev, where a house and a farm burned down after being sprayed over by burning gasoline. Of the crew four were killed in the crash, while four landed alive in their parachute. Three of them were helped to Sweden, but the bombardier Walter J. Kita had hurt his shoulder so badly by the landing, that he asked to be brought to a hospital, where the Germans picked him up as a POW.

At their landing right south of village Hyllested at the farm of Frederik Hansen the co-pilot and radio operator were relieved by their parachutes by the carpenters Evald Petersen and Joergen Rostgaard. Thomas R. Murphy handed over his flight suit and boots to them. A schoolboy Ejvind Friis Jensen showed them a hiding place in a small pine wood along the railroad, from where they jumped a local bus, and went on at their trip to Sweden and back to England. Joergen Rostgaard used these flight boots for many years driving his motorcycle. But when the zippers were worn out, he got the local shoemaker Carl Petersen in Hyllested to replace them with some straps and buckles, and he could use them for a number of more years.

After Joergen Rostgaard passed away a little past Christmas 2002, his widow Inge Rostgaard offered the boots to Ejvind Jensen in Kvislemark. In agreement with daughter of the radio operator Mrs. Marie Morris in San Leandro, California it was decided, that they were handed over to Skaelskoer Museum, as they are also a part the history of Denmark.

USAAF flight boots handed over to Skaelskoer Museum July 8, 2003

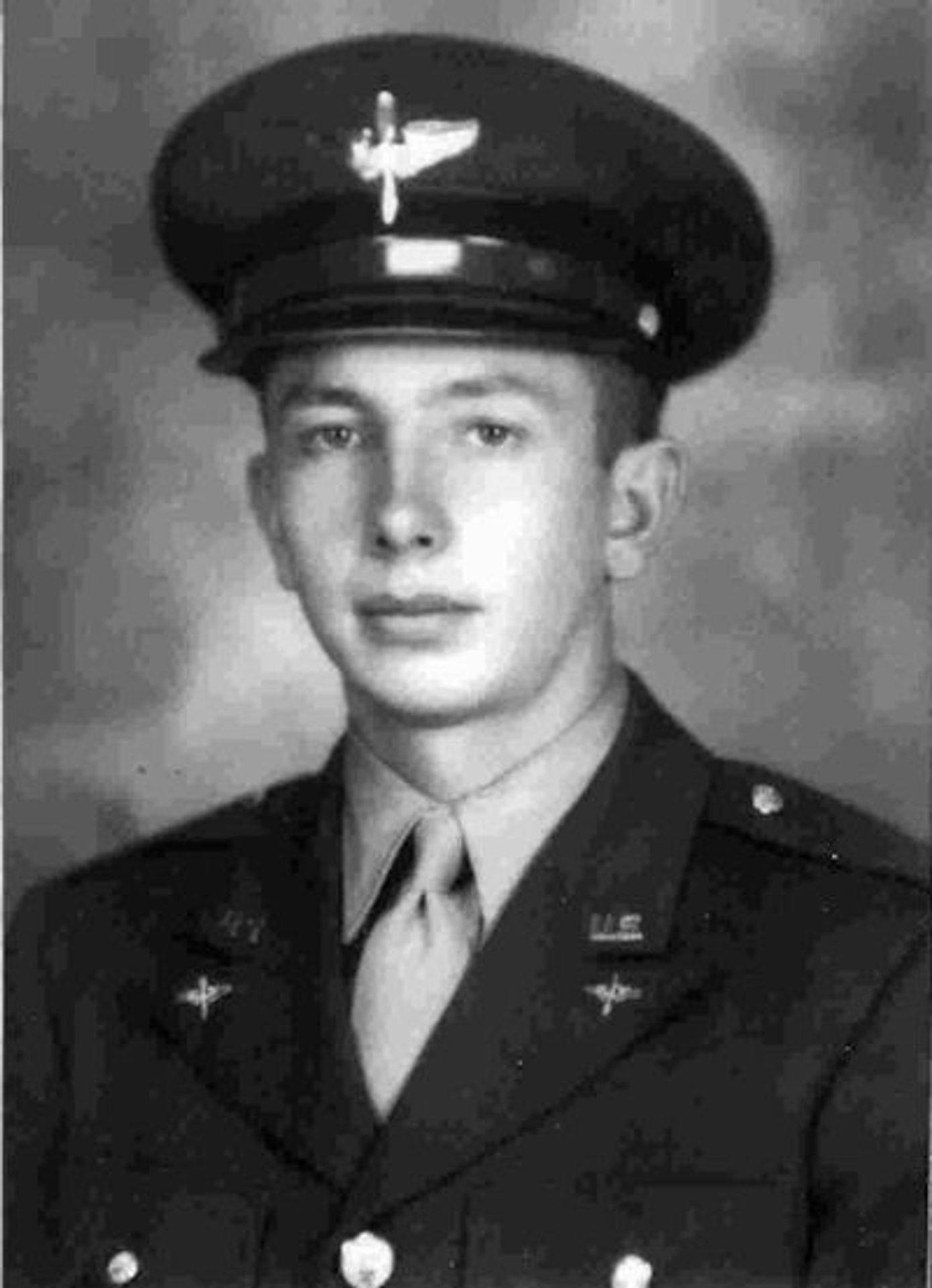

S/Sgt Sidney Sheren

Tonopah, Nevada 1943

Covered by his partially deployed parachute

Photos: Alan Sheren

CBU Naestved Rescue Team

The following photographs were very generously supplied by Bent Esbensen of Denmark. His father, Svend Henry Esbensen, was part of the CBU (fire brigade) who cleared the Venslev area where Logie’s B-24 crashed. These photos were taken by him at that time. After his service in the CBU, Svend Esbensen joined the Danish Resistance in mid-1944 and served until the end of the war.

CBU Naestved Rescue Team (“White Team”)

(Svend Henry Esbensen is 2nd man from front in the right wing)

CBU team at crash site. The damage to buildings was most likely due to Logie’s crashed aircraft, which “…spread debris over a 7-acre area.“

Parts of an engine and propeller hub; and one of the 500lb bombs from Logie’s Liberator

Members of the CBU “White Team” at the funeral ceremony for members of Logie’s crew

Sgt John H Schramm is laid to rest at Venslev Cemetery (later moved to Svino Cemetery)

Members of the Danish Resistance. Svend Esbensen is wearing the white coat in center.

Stars & Stripes Article

Courtesy: Robert Nixon via Fred Allison

My father had this same article in his papers. He had written in the margin in red grease pencil, “This is Logie’s crew. We checked the home towns.” Unfortunately I have misplaced my copy, so I am very grateful to Fred Allison, son-in-law of Robert Nixon, navigator from Glenn’s Crew (#73) for sharing.

The Evaders Return

Byron Logie, George Reed, Thomas Murphy

Courtesy: Bert Betts

Memorial Stone – Venslev, Denmark

A QUIET AND CORDIAL DANISH HOMAGE TO FALLEN ALLIED AIRMEN

A translated article appearing in the Danish newspaper “Naestved Tidende” May 7, 1945, the second non-censured paper after the liberation:

The memorial service yesterday at Svinoe cemetery, where 100 allied airmen are put to rest. Citizens of Naestved will set up a monument.

In early May 1942 the German commander on navy air force base Aunoe asked the council of Svinoe church council, if they would make space on Svinoe cemetery for a shot down fallen allied airman. From Danish aide this request was delightfully accepted, as an allied airman, killed by the Germans during his job fulfilling his duty fighting against Nazis and for democracy, was a near friend of Denmark, a brave ally, who Danes liked to bury side by side to Danish men and women. This burial was the first of 100. Nobody knew at that time, that the number would be that big.

German desecration of airmen graves

The German “Reich’s” war against the dead.

In the beginning the German buried the allied airmen with full honours singing hymns, a speech and firing an honour salute by the grave. The first burials were attended by Danish authorities represented by chief of police Borberg, Vordingborg and superintendant of police Krogh and others. From the Danish side was delivered wreaths with Danish flag coloured (red/white) ribbons The Germans also brought wreaths.

A great part of the burials was in the time Easter 1943 to November 6, 1943 done by the Reverend Lindeloev in Koeng, and even if the burials took place at 6:00 o’clock am, people from the parish showed up to honour the allied airmen.

After awhile the German attitude changed, no more honour salute, the German commander was replaced with a sergeant; the local people could no more attend the burials. The Reverend Linde1oev was told to stay away. He kept coming, but after a prohibition November 6 he had to stay away.

Without ceremony of any kind the Germans dug their dead opponents in the ground on Svinoe cemetery, and sometimes they did not allow the names of the deceased airmen to be written in the church file. There are still tombs with unknown airmen on the cemetery.

But the Germans were not present, when Reverend Lindeloev after the service gathered the congregation at the allied war graves and in a good Christian manner made a Danish funeral – the last church ceremony, which was denied the allied airmen by the Germans.

They did not see the congregation place flowers and wreaths in the allied colours on the graves, but they were not ashamed to move these flowers and throw them on the manure pile. That was the German “Reich’s” last greeting! While Gestapo were torturing Danish patriots, the German Wehrmacht (army) derided the deceased allied airmen and ravaged their graves.

Righteous, but powerless indignation

While the German commander still attended the funerals, he asked reverend Lindeloev to shorten his speech the most possible, and later he forbid him to speak at all and allowed only the Reverend to say a short prayer and sing only a single verse of a hymn.

The population were looking with powerless indignation, how the flowers were moved from the graves, while weather and wind blurred the foreign names on the plain wooden crosses, which the Germans spend on the first 5-6 graves. But German gun-barrels kept them on distance, and they had to swallow their indignation.

The last funeral took place Sept. 17, l944. Later on the Germans buried the fallen allied airmen on the beaches and in the fields, where the bodies were found.

And then came May 5, 1945

The memory of the allied airmen is honoured.

Yesterday the Reverend Lindeloev had a memorial service in Koeng and Svinoe churches, both were filled up to the last seat. After the service in Svinoe church the congregation gathered at the war graves for an emotional memorial ceremony. The Reverend Lindeloev announced, that a committee from Naestved had begun collecting money for a monument honouring the fallen airmen.

After the hymn “Til Himmelen Raekker…” Reverend Lindeloev said among others: “Since May 9, 1942 we have buried 100 young men fallen in the war, allied airmen, whom the Germans in the beginning buried in full military honour, but later it was with German resistance, we consecrated them to God’s peace. Several men were buried in their war uniform without ceremony of any kind, but I can say: Each one is buried in an Christian manner under prayer and singing of hymns. They fell in the fight for a cause, which also was the cause of Denmark , and on this place we will honour their memory. They shed their blood, and thanks to these young men and many others we are today a free people.”

The congregation will protect the graves

Chairman of the parish council Ole Jensen, Koeng, who often attended the airmen funerals on Svinoe, said: “Three years has passed, since we were burying the first allied airman. We always met something cold by these funerals and this cold was the attitude of the Germans. But the congregation will know to protect these graves, which we were forbidden to decorate by the Germans, as we wished. We will honour the memory in acknowledgment of what they have done for Denmark and the Danish people. They gave their lives in the fight for a good cause. I would like to express a thank you to those from out of our parish, whom have wished to attend today, and to those whom have taken the initiative to erect a memorial stone.”

No loving hands laid them in the grave

A committee of citizens of Naestved were represented by doctor Bo Poulsen and wife, hardware storeowner Scheel Bech and gardener Nielsen and wife. After having told about the plans of the committee and also thanked the congregation that the committee could attend today, Bo Poulsen said: “In the middle of our great joy over the liberation we are thinking of those, who sacrificed their lives for our freedom, and so we are also thinking of the allied airmen buried here on Svinoe cemetery. No loving hands were closing their eyes, none of their nearest relatives followed them the last way to the grave here on a Danish cemetery far from their homes. They were buried by enemies in a foreign country. Now we are wishing as a small expression of our respectful gratitude to honour their memory by creating a beautiful frame around their last place of rest. With resentment we have seen, how a big nation have treated their deceased enemies, and today we will place flowers on their graves.”

Then the committee placed flowers on the graves of the airmen in presence of the congregation. The crowd was enlarged by a lot of people from Koeng. Already earlier in the day there were placed flowers on the graves and more were added. The Reverend Lindeloev expressed a thank you to the Naestved Committee and everybody, who took part in the memorial ceremony, said the benediction, and before everybody left the scene a hymn was sung.

Article and photo: Alan Sheren