Koehn Crew – Assigned 752nd Squadron – July 31, 1944

Lost on Truckin’ Mission September 24, 1944 – MACR 9574

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Crew Position | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2Lt | George J Koehn | 0699697 | Pilot | 24-Sep-44 | KIA | Netherlands American Cemetery |

| 2Lt | John R Tucker | 0767914 | Co-pilot | 24-Sep-44 | KIA | Netherlands American Cemetery |

| Capt | Lawrence R Fick | 0719042 | Navigator | 23-Jan-45 | CT | 752nd Squadron Navigator |

| 2Lt | James A Soesbe | 0716983 | Bombardier | 24-Sep-44 | KIA | Netherlands American Cemetery |

| S/Sgt | Anthony J Corlito | 31203718 | Radio Operator | 24-Sep-44 | KIA | Netherlands American Cemetery |

| S/Sgt | Merlin T Ash | 39278839 | Flight Engineer | 24-Sep-44 | KIA | Netherlands American Cemetery |

| S/Sgt | Clifford Gowin | 35483385 | Aerial Gunner | 17-May-45 | UNK | Trsf to 752nd Sq - Vermieren crew? |

| Sgt | Billie Hudson | 6972473 | Aerial Gunner | 24-Sep-44 | POW | Stalag IIIB |

| S/Sgt | Robert O Shea | 11057836 | Aerial Gunner | 01-Oct-44 | UNK | Repl on Lehr crew? |

| Pvt | James R Southern | 34772775 | Aerial Gunner | 08-Nov-44 | RECLS | Reclassified Airplane Eng Mech |

After being assigned to the 752nd Squadron on July 31, 1944, George Koehn’s Crew began their combat tour with a mission to Hamburg on August 6, 1944 – a tough one to start on. Their ninth (and what would prove to be their last) combat mission 36 days later was another tough one – Magdeburg. That mission, on September 11th was the last combat mission that the 458th would fly that month. The group, along with several other groups from the 2nd Bombardment Division, was pulled off of operations and assigned to fly gasoline to Patton’s army in France. The 8th Air Force called these “Truckin’ Missions“, but aircrews received no mission credit.

On September 23rd Koehn and a skeleton crew boarded a Liberator borrowed from the 703BS 445BG, B-24H-15-FO 42-52348 named Lady Shamrock, and took off with their gasoline cargo. They arrived at their destination airfield, offloaded their cargo, and as it was too late to return to Horsham, spent the night in France. They were reported to have taken off the next morning, but never returned to Horsham. No one would know what happened to the crew until after the war. 2Lt Harold Coburn was aboard this flight as navigator. He was assigned to the 752nd Squadron on September 15, 1944 as navigator on the crew of 2Lt Clyde D. Simpson. He was listed as MIA (later DED) only nine days after arriving in theater.

Navigator, 2Lt Lawrence R. Fick flew the rest of his missions as a lead navigator with the crews of pilot’s John Moran and Charles Lockridge. Sgt Robert Shea is shown flying missions with Lt Robert B. Lehr and crew who completed their tour in March 1945.

————————-

MACR 9574

Plane took off from AAF Station 123 for St. Dizier, 23 Sep 44. No further definite information available. However it is assumed to have taken off on 24 Sep 44 for Home Station, AAF 123, and the only known information is that it did not return to AAF 123. Since A/C was temporarily assigned this Station for TD (Temporary Duty) and home station [for aircraft] is unknown the [serial] number of engines and armament is not available.

Missions

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 06-Aug-44 | HAMBURG | 106 | 1 | 42-52455 | O | 7V | 49 | PLUTOCRAT | |

| 07-Aug-44 | GHENT | 107 | 2 | 41-28942 | U | 7V | 24 | HEAVENLY BODY | |

| 09-Aug-44 | SAARBRUCKEN | 109 | NTO | 41-29352 | K | 7V | -- | WOLVE'S LAIR | NO TAKE OFF - REASON UNK |

| 12-Aug-44 | MOURMELON | 111 | 3 | 41-29352 | K | 7V | 48 | WOLVE'S LAIR | |

| 14-Aug-44 | DOLE/TAVAUX | 113 | 4 | 42-95050 | J | 7V | 40 | GAS HOUSE MOUSE | |

| 18-Aug-44 | WOIPPY | 116 | 5 | 42-109812 | V | 7V | 39 | UNKNOWN 016 | |

| 24-Aug-44 | HANNOVER | 117 | 6 | 42-50314 | L | 7V | 48 | ETO PLAYHOUSE | |

| 09-Sep-44 | MAINZ | 124 | 7 | 42-50499 | F | 7V | 10 | COOKIE/OPEN POST | |

| 11-Sep-44 | MAGDEBURG | 126 | 8 | 42-50504 | D | 7V | 3 | UNKNOWN 019 | |

| 23-Sep-44 | HORSHAM to ST DIZIER | TR07 | FTR | 42-52348 | T1 | NOT 458th A/C | SHOT DOWN TRUCKIN' FLIGHT |

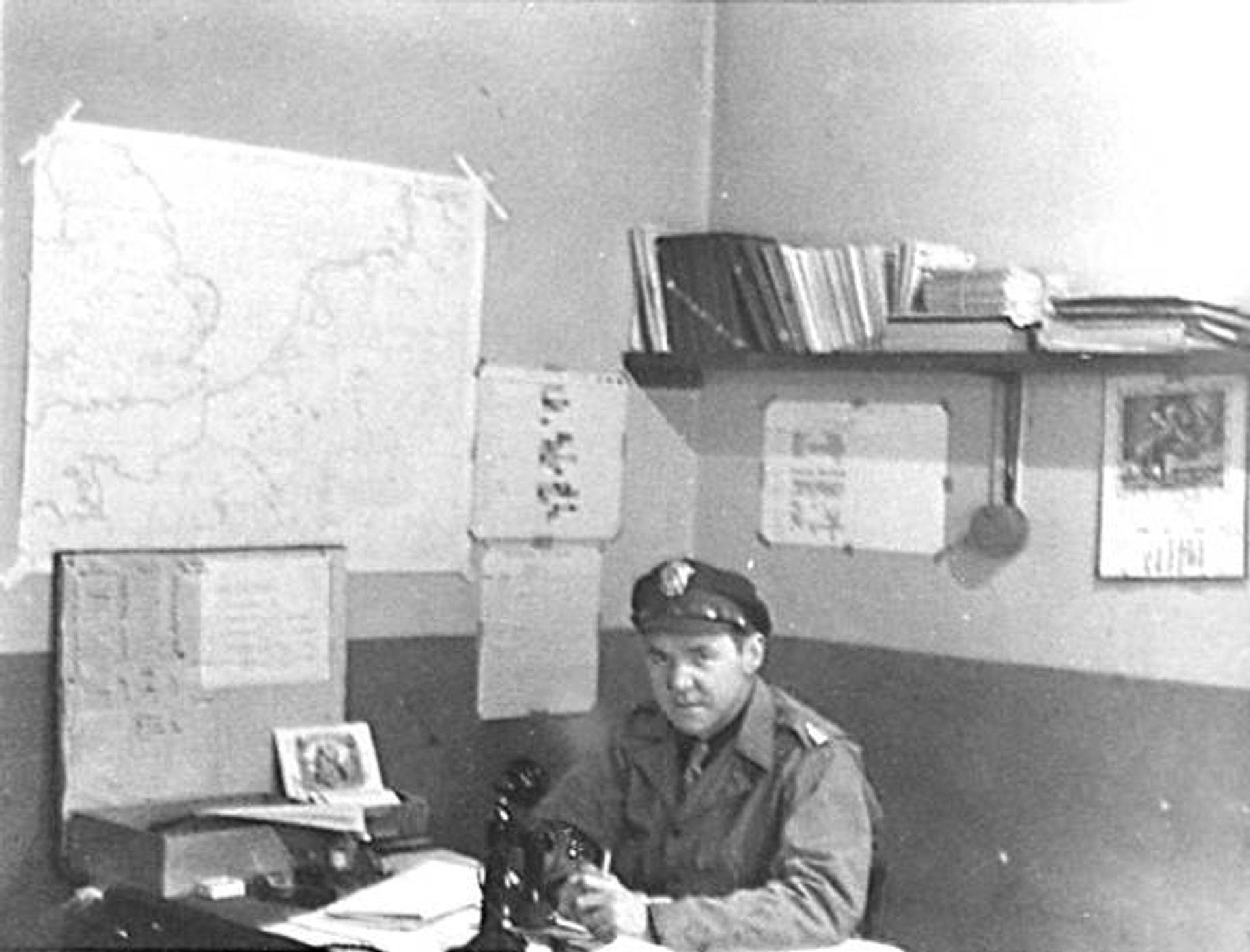

Capt Lawrence Fick

In early September 1944 the 458th Bomb Group was stood down from bombing missions and assigned to hauling gasoline to General Patton’s rapidly advancing armored forces. The first planes were dispatched on September 12, 1944. Those planes were equipped with two of the large tanks in the front bomb bays that we had used when we flew across the Atlantic, some gas was stored in two of the wing tanks and five gallon Jeep cans were stored in the waist. The planes could only carry a little over 1,000 gallons in that configuration. During the next six days, trucks were sent to supply depots all over England to gather P-51 and P-38 drop tanks. The P-51 tanks were placed in the waist section of the planes and the large tanks remained in the front bomb bays. For the rest of the missions the planes were able to haul over 1,590 gallons per trip. The groups that were assigned to hauling gasoline were sent war weary B-24s from the other bases, so we were flying planes with all sorts of tail markings. We were not flying in formation so group identification was not important.

During the time of the gas haul missions, the lead crews were supposed to get some more training. Our crew was a lead crew just getting our start at deputy squadron leads.

The crews for gas hauls were made up of the pilot, co-pilot, navigator, flight engineer, and radio operator. The pilots were permitted to take two passengers on each trip. When I met Bob Shea, our tail gunner, at a reunion many years later, he told me that the non-essential members of the crew had drawn straws to see who could go as passengers. Jim Soesbe and Bob Shea drew the long straws. Bob did not want to go and gave his straw to Billie Hudson.

After a couple of days of dispatching the gas hauling crews, Colonel Williamson, the 752nd Squadron Commanding Officer, decided to go to the receiving bases to see if the unloading operation could be improved. Col. Williamson and the executive officer were both command pilots so they decided to make up an office crew rather than hitch a ride with one of the regular crews. The colonel flew as first pilot, the exec as co-pilot, I was the navigator, the squadron clerk (a flight engineer who had completed his tour) as flight engineer and a pick-up radio operator.

After six days of hauling gas, the group staff decided to send the lead crews on the gas haul too. Since I was in Lille, France with Col. Williamson when Koehn’s crew was to take a load of gas, they assigned another navigator, 2Lt Harold Coburn, in my place. He may have just arrived at the base or he may have been from another crew that was not flying for some reason. If he was new to the way things worked in combat, he may not have had sufficient briefing. The briefings for the seventh day of gas hauls may not have been adequate for someone going on his first trip. Also, since we were using war weary ships from another base, the GEE box may not have been working. We were briefed to fly between 500 and 2,000 feet and that makes pilotage navigation a little difficult. You can’t see as many check points as you can at much higher altitudes. The plane arrived at the designated destination in good shape, so the hardest part of navigation was done. The crew departed the next day for the return to Horsham.

On my return to base from Lille, I discovered that my crew was gone. After two days of checking and waiting, I convinced group communication to radio St. Dizier to see if they had arrived. The message I was given was that they had arrived safely and had departed on September 24th for their home base. The bases between St. Dizier and Horsham were contacted to see if they had landed at any of the old German airfields that were being used by the Allied Air Forces. There was no report of the ship landing at any of those facilities.

Based on what little information I had, I assumed that they had gone over one of the areas along the coast where German troops were still holding out and had been shot down, going into the Channel. A chart that I have for the November 25, 1944 mission still showed areas along the coast from Voorne (near Rotterdam) to the Zuider Zee where the Germans still had anti-aircraft guns capable of doing damage to a high flying formation. We were flying the gas hauls at very low altitudes easy targets for even small arms fire.

After a little time had passed, I started writing letters to Mrs. Koehn, Betty Soesbe, Betty’s mother, and Dale Tucker. I felt I was not divulging any military secrets when I told them what I suspected. Betty always wanted to know why Jim (pictured at left) was with the crew [on that mission].

It was the mid-1960s before I had any more information about the crew. My family made a trip back east and we stopped to see Alma Koehn in Cleveland, Wisconsin. She had been in contact with Billie Hudson’s sister and found out that Billie was badly burned and had been a prisoner of war. I was happy that he had survived, but was puzzled as to how he became a prisoner. Had the Germans taken a boat out and pulled him out of the Channel? I didn’t ever consider that the plane had been shot down over dry land.

I had no more information until a few days ago when I got a phone call from Darin Scorza who lives in Overland Park, Kansas. His father was a navigator in the 458th Bomb Group and he is gathering material for a book. He was comparing the list of the names on the Missing Air Crew Report (MACR) for Koehn’s crew and the crew list for Koehn’s crew when it arrived at Horsham St. Faith, and he noticed the difference. He got my address from the 2nd ADA roster and gave me a call. He told me some interesting things that he had learned from the MACR on Koehn’s plane, the casualty reports that Billie Hudson had filled out, the list of gas haul days, the destinations of the missions and from Jim Soesbe’s brother, a report from the Dutch Coast Guard that wreckage of Koehn’s plane had been found.

Based on information that I now have, I feel that the following is the story of George Koehn’s crew activities from September 22nd to 24th. Koehn’s crew was placed on the dispatch board on the night of September 22nd. They reported to briefing on the morning of September 23rd and were assigned a substitute navigator, 2Lt Harold Coburn (right).

The crew departed from Horsham St. Faith and arrived safely at the assigned destination of St. Dizier, which was not too far from the front lines. After off-loading their cargo of gasoline it was too late to return to Horsham, so the crew stayed the night. On the morning of September 24th, the crew departed from St. Dizier and headed for their home base. They would have been flying low over the approximate route that they had used on the trip the previous day. According to Hudson’s casualty report, he heard Soesbe say, “The damn fools are shooting at us!” before the inter-phone was knocked out. The route back to Horsham should have crossed the coast line at the Belgian-Dutch border, but they may have drifted a little to the right of the direct route. Also, there may have been pockets of Germans that did not show up on any flak maps. No one will ever know for sure. Hudson could not contact the flight deck again and flames were apparently going through the fuselage. He bailed out of a waist window, but not before he was badly burned. After he bailed out the ship exploded. All of those empty drop tanks in the bomb bays made the returning planes flying bombs. His parachute apparently was not too badly burned and he landed in an area where he was taken prisoner. His burns were severe enough that he was treated at a German hospital.

Now we know the plane was still over Holland when it blew up and close enough to the coast for the wreckage to have been found by the Dutch Coast Guard so close to the safety of the English Channel.

The only questions that I still have are:

1.Was Coburn new to the operations of a combat bomb group, or was he from some crew that had flown several missions? [Updated above, Sept 2012]

2.Where was the hospital that provided medical care for Hudson?

3.Was Hudson a prisoner until the end of the war or did the area where he was held prisoner surrender before VE Day on May 7, 1945?

It has been almost 61 years since the crew went down. I think that the story is almost complete thanks to the radio report from St. Dizier, and information from Mrs. Koehn, Bob Shea, Robert Soesbe, and the research of Darin Scorza.

Compiled from correspondence with Larry Fick, 2005