Klusmeyer Crew – Assigned 755th Squadron – August 10, 1944

Bottom Row: Joseph Pohler – WG/2E, MC Miller – Pltg N (not regular crew member)

Not Pictured: Raymond Sills – G

Shot down October 14, 1944 – MACR 9487

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Pos | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2Lt | William Klusmeyer, Jr | 0439198 | Pilot | 14-Oct-44 | POW | Stalag Luft III |

| 2Lt | Frederick W Wright | 0825053 | Co-pilot | 14-Oct-44 | POW | Stalag Luft III |

| 2Lt | Robert F Ferrell | 0722831 | Navigator | 14-Oct-44 | POW | Stalag Luft III |

| 2Lt | Ernest M Sands | 0773340 | Bombardier | 14-Oct-44 | POW | Stalag Luft III |

| S/Sgt | Richard J Shearer | 37477450 | Radio Operator | 14-Oct-44 | POW | Stalag Luft 4 |

| S/Sgt | Joseph G Pohler | 6997946 | Flight Engineer | 14-Oct-44 | POW | Stalag Luft III |

| Sgt | James T Carlisle | 14201433 | Aerial Gunner | 14-Oct-44 | POW | Dulag Luft - Gross Tychow |

| Sgt | Terrell Fricks | 34770126 | Aerial Gunner, 2/E | 14-Oct-44 | POW | Camp unknown |

| Sgt | Vernon A Hanes | 39332218 | Armorer-Gunner | 14-Oct-44 | POW | Stalag Luft III |

| Sgt | Raymond Sills | 12175566 | Aerial Gunner | Oct-44 | CT | Trsf to RD for return to ZI |

Klusmeyer’s crew was assigned to the 755th Squadron in the summer of 1944. Most of the crew had flown seven missions before the October 14, 1944 mission to Cologne. On that day 2Lt Millard C. Miller, the navigator from the crew of 2Lt Stanley A. Sievertson, was assigned to Klusmeyer’s crew as pilotage navigator. Klusmeyer was assigned the deputy lead of the trailing section and required the extra set of eyes with a map in the nose turret. Just after the bombs were dropped, the aircraft received three direct hits from flak and was forced to drop out of formation. All ten men aboard were able to bail out safely and spent the rest of the war in Stalag Luft III and Stalag Luft IV.

S/Sgt Joseph Pohler and Sgt Vernon Hanes somehow ended up at Stalag Luft III, an Air Force officer’s camp. On the MACR Pohler is listed as a 2Lt with serial number O-722560.

Sgt Raymond Sills had received permission to visit his paratrooper brother, injured in Holland during Operation Market Garden, and was not on the October 14th mission. While it is not clear how he managed to fly 35 missions so quickly, Sills is listed in the group records as having completed his combat tour in October and being sent to a Replacement Depot for return to the States.

————————-

MACR 9487

A/C 864 was hit by flak over Cologne at 1235 and dropped out of formation. No. 1 engine was smoking, but A/C was under control when it entered 8/10ths undercast. No ‘chutes reported.

Missions

.

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-Aug-44 | HANNOVER | 117 | NTO | 42-51179 | P | J3 | -- | DUSTY'S DOUBLE TROUBLE | NO TAKE OFF - REASON UNK |

| 25-Aug-44 | LUBECK | 118 | 1 | 42-51179 | P | J3 | 31 | DUSTY'S DOUBLE TROUBLE | |

| 27-Aug-44 | FINOW | 121 | 2 | 42-51179 | P | J3 | 33 | DUSTY'S DOUBLE TROUBLE | MISSION CREDIT IN NOV |

| 01-Sep-44 | PFAFFENHOFFEN | ABN | -- | 42-100425 | O | J3 | -- | THE BIRD | ABANDONED |

| 05-Sep-44 | KARLSRUHE | 122 | 3 | 41-29342 | S | J3 | 45 | ROUGH RIDERS | |

| 09-Sep-44 | MAINZ | 124 | 4 | 42-95120 | M | J3 | 44 | HOOKEM COW / BETTY | |

| 11-Sep-44 | MAGDEBURG | 126 | 5 | 42-95316 | N | J3 | 45 | PRINCESS PAT | |

| 18-Sep-44 | HORSHAM to CLASTRES | TR02 | -- | 42-52293 | G | J3 | T1 | JUDY'S BUGGY | CARGO |

| 23-Sep-44 | HORSHAM to ST DIZIER | TR07 | -- | 42-95219 | W | 7V | T4 | PATCHIE | CARGO |

| 05-Oct-44 | PADERBORN | 128 | 6 | 44-10602 | A | J3 | 8 | TEN GUN DOTTIE | |

| 12-Oct-44 | OSNABRUCK | 132 | 7 | 42-50740 | F | J3 | 3 | OUR BURMA | |

| 14-Oct-44 | COLOGNE | 133 | 8 | 42-50864 | B | J3 | 9 | JOLLY ROGER (II?) | FLAK OVER COLOGNE |

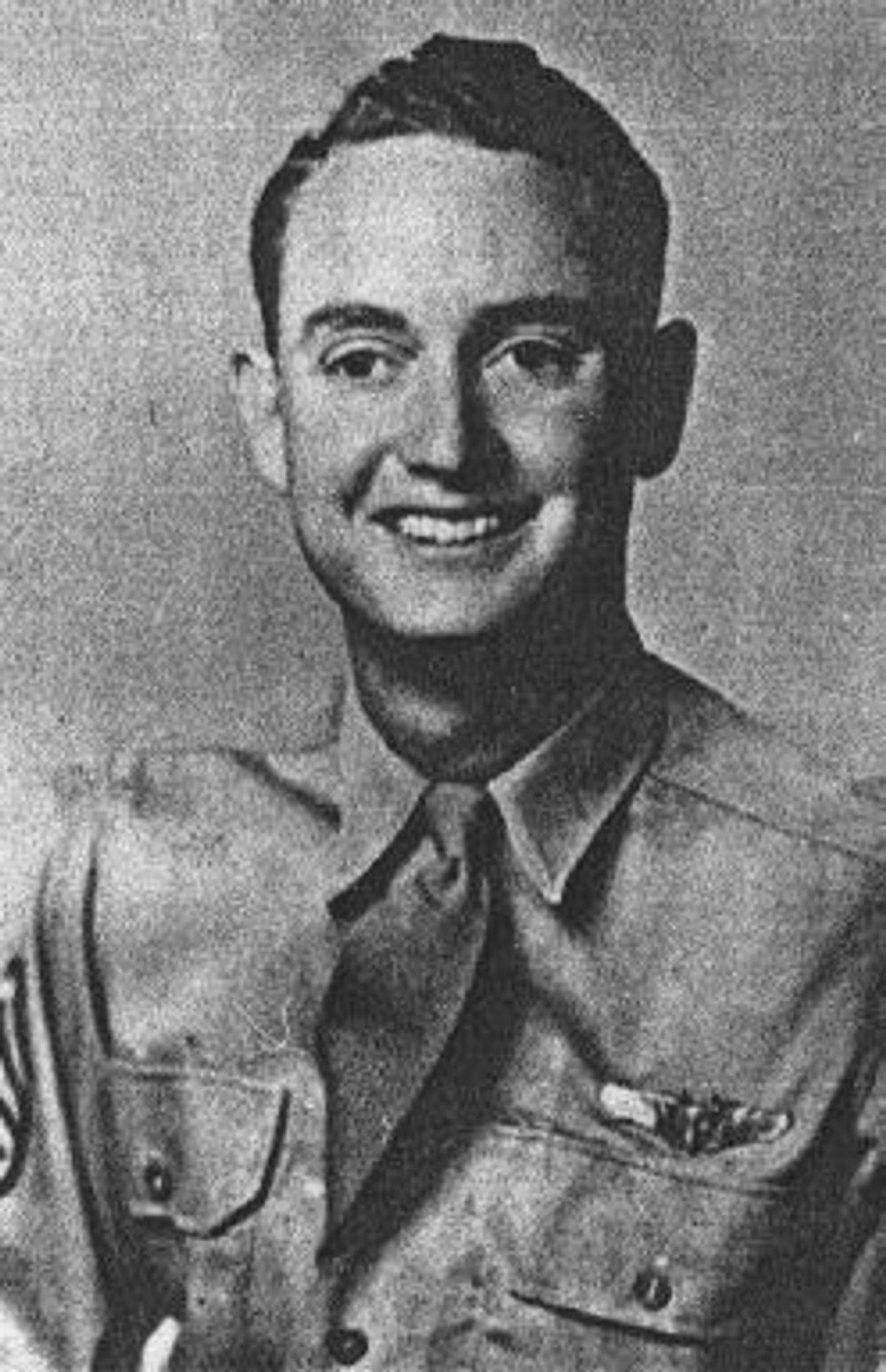

2Lt Robert L. Ferrell – Navigator

Excerpt from Home by Christmas?: The Story of U.S. Airmen at War by Martin W. Bowman

————————-

Another of the men who worked for the “X” organization was Lieutenant Robert L. Ferrell, a twenty-year-old lead navigator in the 458th Bomb Group who had been shot down one week after Karl Wendel, on 14 October 1944. Ferrell recalls, “I worked on the ’X’ committee’s tunnel-digging assignment. Specifically, I was in the dirt-hauling-away detail with pockets sewn in each trouser leg interior and a small hole in the bottom of each pocket with a draw string to keep the hole closed until you wished the dirt to start trickling out.”

It was a far cry from a few weeks before, when on the night of 13 October Ferrell had returned to his base at Horsham St Faith after an evening in Norwich:

“Even though it was 11:30pm when I returned to base, I had to view the crew status board on the wall. The board that would spell out the names of the crew which would mount the mission the next day. Damn it, there we were; Lieutenant Klusmeyer’s crew. We hadn’t flown in three days so I really couldn’t complain. Oh well, up the stairs two steps at a time and down the hall to Room 23 and hope that I don’t awaken Ernest Sands, the bombardier, who is sacked out.

“Sleep came hard for me for Patricia and I had broken up earlier in the evening. She had lost her pilot brother on an RAF raid the night before and she felt she could not stand the anguish of maybe losing two people from her life. We had leaned against the rock wall that surrounded the park where the 6X6 trucks picked us up and expressed our love for each other and I vainly tried to understand her feelings in the matter. I kissed her goodbye, leaving with her my flying scarf that I had made from an old white parachute – a parting token.

“All these thoughts kept running through my mind as I tried to fall asleep for two or three hours. God, don’t tell me that squeaking Jeep brake is the one announcing the arrival of the ‘wake-up’ sergeant. The door opens, the flashlight beam crosses the small room and the booming voice announced, ‘Lieutenant Sands, Lieutenant Ferrell; 03:30 hours. Sign the wake-up sheet here. No over here. Up and at ‘em men!’ The door slams behind him and I feel like I could sleep forever. Feet on the floor, lights on, grab the olive drab colored towel and down the long corridor to the communal bathroom for the morning ablutions and back to the room to dress. The thoughts of what awaits me in the Officer’s Mess is not heart warming. Those same damned powdered eggs, cooked three tons at a time, the greasy bacon would slide off a gravel driveway and that steaming black coffee with the hard English rolls. Oh well, I bet the Roman gladiators were fed better than this ‘but there’s a war on Mac’.

“Push the meal down against an already nervous stomach and head out for the side door and over to the War Room. I never wanted us to be a lead crew anyway. It’s just too much work on the navigator and the bombardier and an easier task for the pilots. The MP’s give you the once over and check your ID card as you troop into the Base War Room with its momentary secrecy. Here the Group CO [Colonel James H. Isbell], the Exec., the various squadron commanders, the lead crews, and the deputy leads are present.

“We are soon hearing what the regular crews will hear some of in a couple of hours from now. It’s the Group deputy lead for us today and that is a better tune. I look about and wonder if we can win this war with all of us 19, 20, and 21-year-old officers? Sure hope so. The CO is a full Colonel and ancient – every bit of 28 and a West Pointer of course. A regular amongst this sea of reservists, but that doesn’t mean five cents to me now for I’m too green to really understand.

“The target – Cologne. Be sure and do your best to miss the Ford Motor Co. factory and the famous cathedral. The whole 8th Air Force will be airborne this day and over 600 enemy bombers will be hitting the immediate Cologne area. The briefing is soon over with its usual precise monotony. A short walk and I am in the crew briefing area and around the corner to the Personal Equipment Section. The parachute, the parachute bag, the oxygen mask, ’45 and shoulder holster, three clips of ammo, the new two-piece electric flying suit, flak helmet, three flak vests (two to stand on) and all my navigational paraphernalia. Then off to the Briefing Room.

“The crews begin to gather and soon the Catholic chaplain is giving the prayer to all us Protestants. Announcements over and with the gesture of a sculptor undraping a new statue, the Exec’ pulls aside the pool-table-green-colored cloth to expose the routing, the IP (Initial Point), the target, the RP (Rendezvous Point) and the course home. The Intelligence officer gives his estimate of the number of stationary flak units as well as his guesstimate of the number of mobile flak railway batteries that will be rushed into the target area. The near reverent silence is broken by the in-sucking of air by astonished crewmen. What a way to earn a living, but there is more mileage in an ounce of patriotism than a ton of money. ‘Pilots stay in here for your briefing. Navigators, bombardiers, radio operators, and gunners to your respective sections for sectional briefings. Crews dismissed!’

“All the navigation work is done and now to drag that parachute bag out to the 6X6’s waiting bumper to bumper to transport some 500 of us crewmen out to the bomber hardstands. I note the refuellers are still topping off the tanks on the three birds on our hardstand area. The armament men are still putting the standard 500 pounders in our bomb bays. The incendiaries are already loaded on the top shackle – one per stanchion. The red flag streamer is attached to each incendiary to denote to the aircraft behind us that we are a lead crew. Sergeant Sills, the tail turret gunner, will not be flying with us today, as he received permission to visit his wounded paratrooper brother who had been brought back from the debacle earlier at Arnhem. But no need to worry for we will be well covered by the ships coming along behind us since we are flying up near the front as deputy lead. I look at the ball turret gunner; a mere boy of 17. The oldest man on the crew is middle aged – he is the 24-year-old engineer top turret gunner. He is also second generation German as is our first pilot.

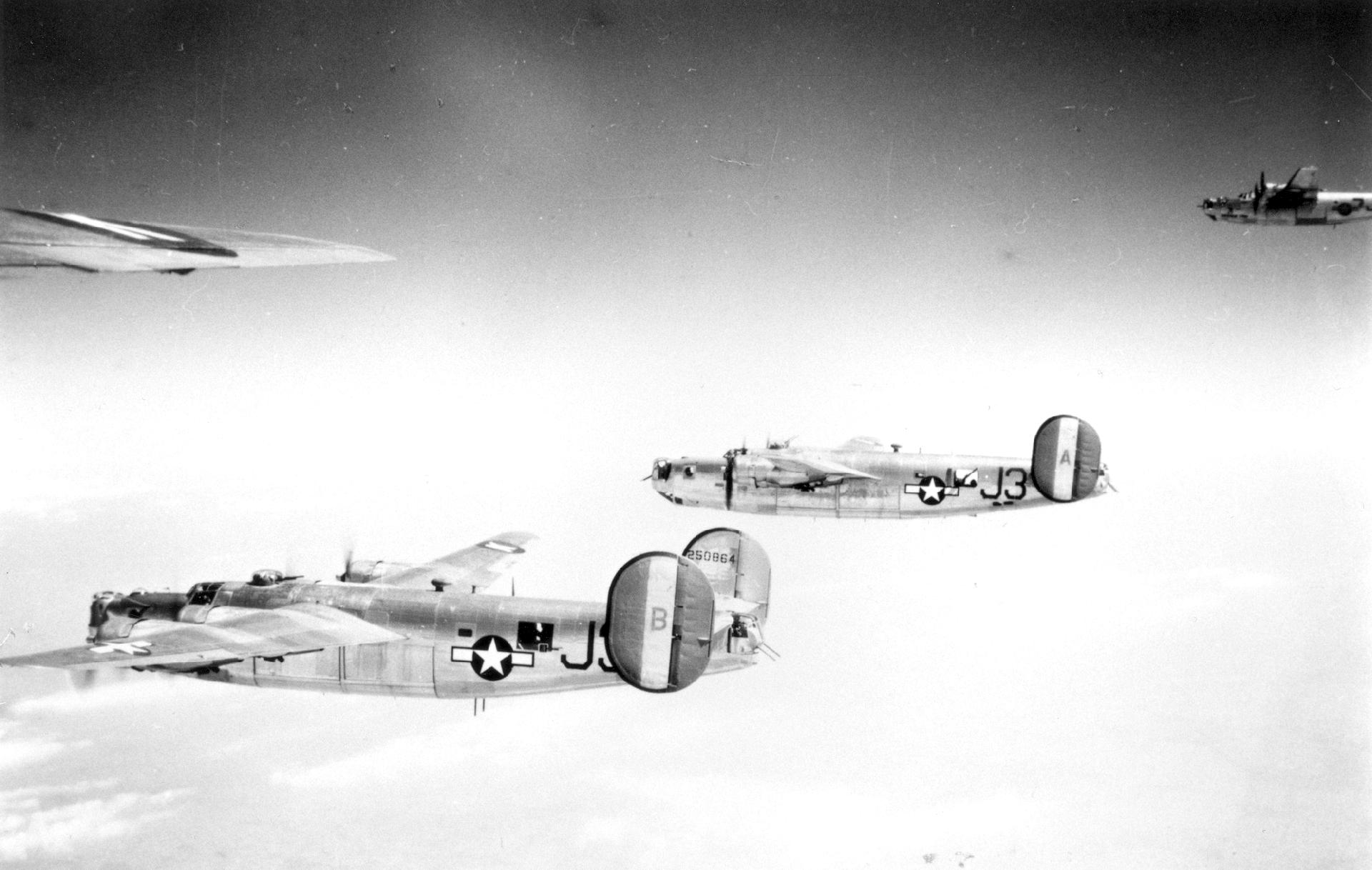

“Everyone is in his position and the flares arch skyward from the walk around area just outside the control tower. The engines start on the 49 B-24’s: a maximum effort this day of four squadrons and twelve airplanes per squadron plus the stripped down and gaily-painted assembly mother ship that will leave us and return to base in about an hour. We roll down the runway aboard The Jolly Roger just after the lead ship is airborne. Its 07:52 and wheels are up and in the wells.

(Mike Bailey)

“The laborious and time-consuming task of assembling the 48 bombers is accomplished by the time we are outbound from a point north of London heading for the Dutch coast. The placidity of the deputy lead ship is soon broken by the radio crackling, ‘Lincoln Red Leader to Foxtrot Two: Take over the lead as we are going down with engine trouble. Acknowledge.’ I jam my flak-helmeted head into the deep plastic bubble on the port side of the navigator’s compartment to see the lead drop its wing and turn down through the clouds to the left. It was swiftly soaking through to me, so I got up on my tip toes and peered out the astrodome. God, the sky is filled with bombers and they are following us. Us – who is guiding us? Me!

“The sobriety of the crew is awesome. Through the breaks in the undercast we can see the Zuider Zee below and with tradition, we clear our machine-guns by firing down into the Zee. The left gun on the Emerson nose turret, being operated by Millard C. miller, my second navigator, proves to be frozen. Miller has been put on the crew just for today’s mission and he is to provide me with an extra set of eyes, keep the fighters off our nose and provide me with current pilotage data.

“We are now two minutes behind the master schedule, but when we approach the IP we can pick it up by shortening the corner. The cold in the compartment and the heavy anti-aircraft firings help to keep my mind off of my awesome responsibility. Graduating second in my class is not much comfort to me right now with a reported 587 of the original 600 bombers still left and following along behind us. With the plastic code flimsy in my hand, I call the radio operator sergeant and read the hourly code to him and we discuss the message that he is to transmit when we reach the IP. Well, here it comes – the IP – still alive and intact. Cut the corner short now. Straighten her out, level it up.

“Since our Jolly Roger is a B-24J, I am facing forward and the navigator’s table folds down to provide work space and to allow the second navigator to crawl across it to get through the two narrow doors into the Emerson nose turret. William Klusmeyer turns the aircraft over to the bombardier and we start running straight and true, hoping the flak will allow us to pass through to the target. Keep an eye peeled for those Bf 109’s and Fw 190’s. The target is almost below us now and we could get out and walk around on the flak – it’s so heavy. Looks like a box barrage.

“With his eye glued to the Norden sight, the bombardier shouts, ‘Bombs Aw…’ The Plexiglas of the Emerson nose turret turns red with blood, the bombardier is blown from over the bomb sight back into the nose wheel well, my left hand is showing blood through my gloves from three shrapnel piercings and the smell of cordite seeps through my oxygen mask. There is a wind blowing inside the aircraft, the communications are knocked out so I can’t check with the rest of the crew. I crank the nose turret to the ‘0’ position, push the bar handle holding the two tiny doors closed down to full open, slip my hands under the second navigator’s arm pits and pull on him. His head falls back against my right shoulder. I look at Miller and vomit into my oxygen mask and nearly drown from it. I have never seen a human head hit by a shell. I pull him out and lay him on the strewn floor of the navigator’s compartment. Taking a scrap of paper, I write a terse note to the pilot to send some help forward and then I pass the paper through the crack between our compartment and the pilot’s feet.

“Sergeant Pohler, the engineer/upper-turret gunner, crawls forward on his hands and knees through the tunnel that connects us with the rear of the flight deck area center and behind the radio operator’s position. He shakes his mask loose from his walk-around oxygen bottles and shouts in my ear that the second shot of flak has blown a large hole in the aircraft at the radio operator’s station below the right wing root, the third shot hit below the ball turret and blew its glass away. Fortunately, the gunner was not inside the ball turret at the time since the fighters steer clear of the heavy flak. The last I see of the second navigator is when Pohler is dragging him by his harness back up through the tunnel and toward the flight deck. (Miller was thrown out the bomb strike camera hatch opening after Pohler secured a 25 ft static line clip to his “D” ring).

“With a note of the macabre, I make an entry into my navigation log explaining the absence of the required number of fixes. I write it in the blood lying on my table. All this time the aircraft is making a slow, wide turn to the right because its controls are shot away and the number three engine is knocked out. We are slowly losing altitude. The noise of the wind blowing in through the holes in front of the airplane creates an awesome, ghostly sound. The stun of the incident is blown away by the sound if the three rings on the bale-out bell.

“Sands (pictured at left) and I crawl through the tunnel, enter the flight deck and see that all are gone except for the first pilot. He motions us to go rearward for bale-out. We try to get through the bomb bays, but the raging fire drives us back. We return to the front compartment and pull the emergency handle on the nose wheel doors, but they fail to open in response. This is our only way out now. The bombardier stoops over and jumps up and down on the nose wheel doors. They begin to part and fly away. He drops through the opening until his outstretched arms hold him momentarily. He looks at me and shouts above the noise, ‘This sure as hell pisses me off!’ then he drops out and away. I crawl over to the opening and turn to face the front of the ship and follow the same procedure. Then out I go.

“What did the training people back at Pueblo Army Air Force Base, Colorado say to us? ‘Do not open your parachute until you have fallen far enough to be able to readily recognize the objects on the ground for if you open sooner you run the risk of the Germans shooting at you while you are descending.’ What did the altimeter last read – 25,000 ft, 23,000 ft? Hell, I can’t remember now. I am falling and tumbling and falling. My past life rushes through my mind’s eye. Why had I not done more with my life? Why hadn’t I written home more often? Patricia was right after all – a woman’s premonition.

“Have I waited long enough? Pull the ripcord. The ‘chute opens with such a violence that I think my body will split in half. I waited too long to pull the ‘D’ ring. I swing once to the left and start to swing to the right. The ground is racing up towards me. The yellow farm house is just to my left and the ploughed field is below.

I hit the ground like a rock and the ‘chute starts dragging me down the furrows with the German family hot on my heels. I am pulling the bottom shroud lines to start collapsing the ‘chute when rough hands assail me and grab the ‘chute and my .45 from its shoulder holster. They are now sitting on my back and holding my legs and talking to themselves. I then hear in somewhat broken English a phrase that I shall live to hear hundreds and hundreds of time again: ‘For you the war is over.’ It was.”

William Klusmeyer, the pilot, Fred Wright, the co-pilot and Ferrell landed in Boppard, Germany near the same farmhouse. All were taken prisoner almost instantly. The rest of the parachutes were strung out over several miles (Millard C. Miller, the badly wounded second navigator, survived) and although one or two of the enlisted men managed to evade, they were all captured later.

Ferrell continues, “We were held in a fire station and turned over to the 28th Wehrmacht Division who in turn gave us eventually to the Luftwaffe as flyer prisoners came under their domain. Eventually, we were taken to Frankfurt and Dulag Luft. My pilot, co-pilot and I were kept a night or two in a civilian jail in Frankfurt before going to Dulag Luft on 17 October with several other rounded-up crews.”

Drama Over Cologne

Scott Nelson presents his painting to bombardier, Ernie Sands

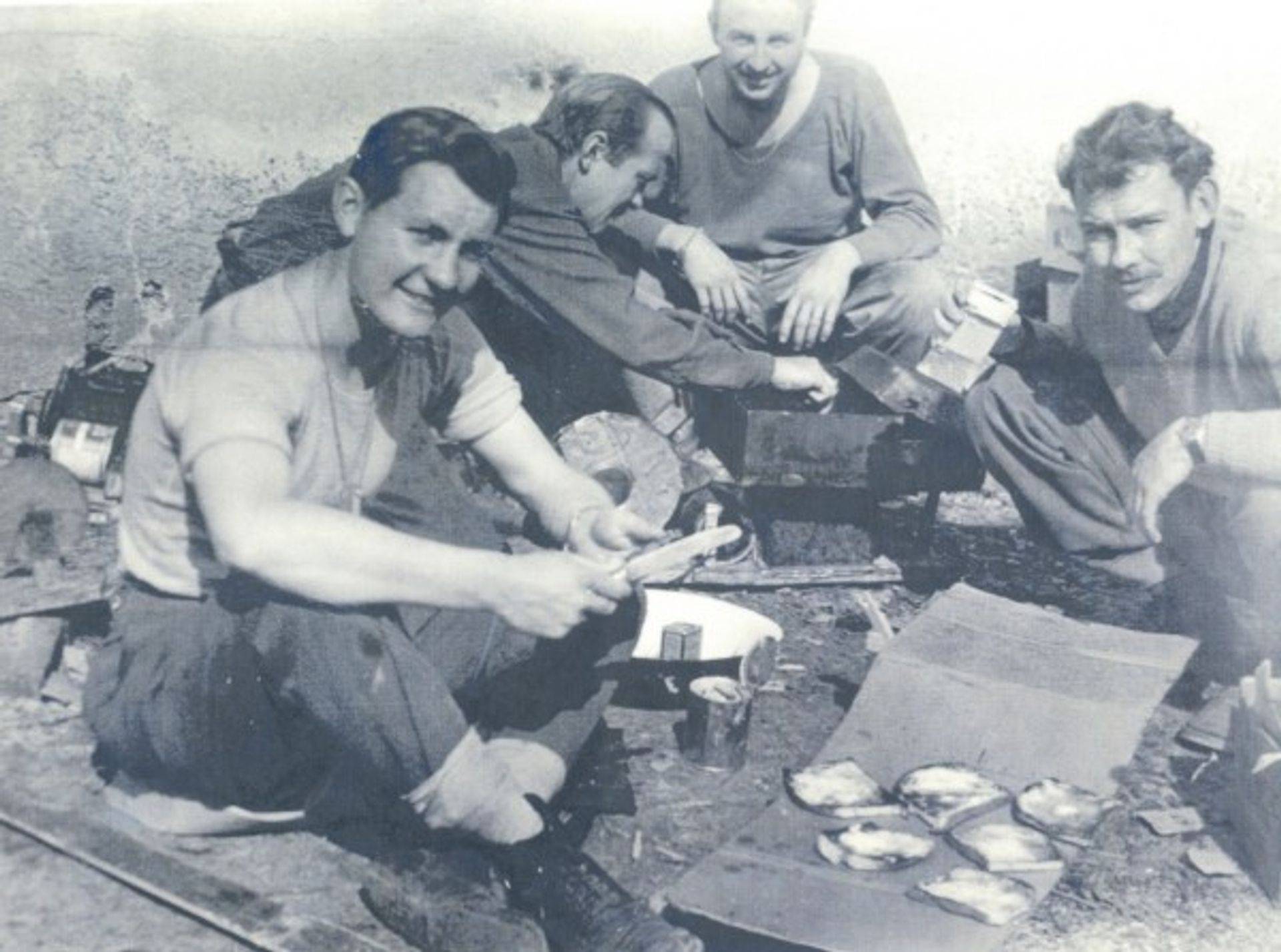

Mooseburg, Germany – 1945

(L-R) John Fitzpatrick (hand in pocket), Ed Stephenson (beret), Ernie Sands (bending over stove), Francis “Fran” Finnegan, John Lindquist, Charles Woehrle, Jim Houser, Lt. Marshall Draper (kneeling) of the 15th Bombardment Squadron. Draper had the unfortunate distinction to be the first 8AF U.S. POW in Germany, shot down on July 4, 1942. These men were roommates at Stalag Luft III, South Compound, Block 130, Room 10. They kept together on the march in January 1945, sharing food and emotional support. Photo was taken at Stalag VII A Moosburg, most likely after hostilities, as Lindquist and Houser are wearing German reversible padded parkas, probably gathered as “war booty”. (Ben van Drogenbroek)

Ernie Sands (L) and Marshall Draper (R)

(Photos: Charles Woehrle)