John Jones Crew – Assigned 753rd Squadron – May 26, 1944

Fuel exhausted – aircraft abandoned over Holland July 11, 1944 – MACR 6929

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Crew Position | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1Lt | John J Jones | 1283784 | Pilot | 11-Jul-44 | POW | Stalag Luft I |

| 1Lt | William R Joyce | 1045479 | Co-pilot | 11-Jul-44 | POW | Stalag Luft I |

| 2Lt | Phil Z Cole | 702148 | Navigator | 11-Jul-44 | POW | Stalag Luft I |

| 2Lt | Glenn L Hargis | 676383 | Bombardier | 11-Aug-44 | TRSF | Trsf to 388BG w/Tooman |

| S/Sgt | George L Eifel | 36735938 | Radio Operator | 11-Jul-44 | POW | Stalag Luft 4 |

| S/Sgt | Jake T Lucero | 39280257 | Flight Engineer | 11-Jul-44 | EVD | E&E Report 2506 |

| Sgt | Charles E Stenard, Jr | 11071476 | Armorer-Gunner | 11-Jul-44 | KIA | Montague City, MA |

| Sgt | Clarence M Prentice | 38022058 | Aerial Gunner | 11-Jul-44 | KIA | El Reno, OK |

| Sgt | Mitchell A Kamenski | 32484628 | Aerial Gunner | 11-Jul-44 | KIA | Bridgeton, NJ |

| Sgt | Robert A Palmer | 37572343 | Aerial Gunner | 11-Jul-44 | KIA | Warren, MN |

John Jones and crew were one of ten specially trained AZON crews who were assigned to the 458th in the spring of 1944. Originally intended for duty in the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater, their orders were changed en route and they flew to England instead.

The four officers, flight engineer and radio operator that had trained together arrived in England in May 1944. The four gunners, not on board the AZON aircraft en route to the combat zone, continued on to the CBI, being replaced by four different gunners once the crew arrived in England. Jones’ crew flew a specially modified B-24J which they dubbed Shack Time from the States to England. This crew flew four AZON missions in June, one of which was abandoned due to poor weather and did not count as a sortie. Crew members, in statements made after the war and in recent correspondence claim they were shot down on their sixth mission, but records indicate that it was their 8th.

On July 11, 1944 Jones’ crew took off for a mission to Munich with the rest of the 458th. This was not an AZON mission (none of which actually occurred in July) but 753rd crews were still assigned to fly with the group. For reasons unknown, Glenn Hargis, bombardier, did not fly on this mission. His place was taken by 2Lt Otto B. Hammersmith, Jr., an original 753rd bombardier on Lt Richard Alvestad’s crew. Suffering battle damage from flak that severed fuel lines, Jones fell back from the formation and eventually descended through the undercast. The order to bail out was given, and five of the crew jumped clear. Jones and Joyce came down in water up to their waist in the sea, just off the coast. They were picked up, along with Phil Cole by the Wehrmacht. Lt Hammersmith and Charles Stenard, nose turret gunner, had gotten each others parachutes mixed up, and one of the chutes spilled on the flight deck. They were evidently unable to get things sorted out in time to bail out. There is a bit of mystery about the three gunners in the rear of the plane.

The B-24 came down near Schoondiyke, 2km southeast of Breskens in Holland and was completely consumed by fire. German records show that the remains of Lt Hammersmith and those of Sgt’s Robert Palmer, Clarence Prentice, Mitchell Kamenski and Charles Stenard were recovered from the wreckage, placed in one casket and interred in the Breskens Community Cemetery. After the war, investigations by the U.S. Graves Registration Service determined that individual identifications could not be made and repatriated the group remains for burial in the Zachary Taylor National Cemetery in Louisville, KY.

However, postwar statements made by eye witnesses to the crash seem to refute that the three gunners, and perhaps Lt Hammersmith are actually buried in the same grave. Many of the eye witnesses state that the Germans only removed one body from the wreckage, that of Charles Stenard, which was then buried in the Breskens Cemetery. Several statements also note that one of the parachutes landed in the water and the man was seen to go under and not come back up, nor did he wash ashore.

2Lt Glenn Hargis continued to fly missions with the group, possibly with the Tooman Crew. He was transferred to the 388BG with Tooman to participate in Project: Aphrodite.

S/Sgt Jake T. Lucero successfully evaded capture after being the first to bail out through the bomb bay. With the help of the Dutch underground, he remained hidden until liberated by Allied forces in October 1944.

————————-

MACR 6929

“An A/C believed to be #341 was seen leaving formation in vicinity of NEUZEN, NETHERLANDS, at 1530 hours, with one engine feathered and another sputtering. It was below undercast. At same time, radio message was picked up presumably from same A/C asking for position.”

Missions

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8-Jun-44 | UNSPECIFIED TARGETS | AZ04 | -- | 44-40275 | L | J4 | -- | SHACK TIME | ABANDONED - WEATHER |

| 14-Jun-44 | 5 TARGETS | AZ06 | 1 | 44-40275 | L | J4 | 2 | SHACK TIME | |

| 15-Jun-44 | 3 RAILWAY BRIDGES | AZ07 | 2 | 44-40275 | L | J4 | 3 | SHACK TIME | |

| 17-Jun-44 | TOURS | 68 | 3 | 42-95018 | J | Z5 | 18 | OLD DOC'S YACHT | |

| 19-Jun-44 | REGNAUVILLE | 72 | 4 | 42-50578 | U | Z5 | -- | UNKNOWN 048 | MSN #2 |

| 20-Jun-44 | ST MARTIN-L'HORTIER | 74 | 5 | 42-50578 | U | Z5 | -- | UNKNOWN 048 | MSN #2 |

| 22-Jun-44 | SAUMER/TOURS | AZ09 | 6 | 42-100408 | D | J4 | 21 | BEASTFACE | TACTICAL BRIDGES |

| 8-Jul-44 | ANIZY, FRANCE | 87 | 7 | 42-100341 | A | J4 | 22 | SATAN'S MATE | |

| 11-Jul-44 | MUNICH | 88 | 8 | 42-100341 | A | J4 | 23 | SATAN'S MATE | FLAK HIT FUEL LINES |

Crew statements from MACR 6929

Casualty Interrogation Report of 1Lt John J. Jones – Pilot

“Jones stated that Sgt. Charles E. Stenard, Jr., was a member of his crew serving in the capacity of nose gunner on a mission dated 11 July 1944. Jones further stated that while piloting a B-24 J on the return leg of a mission over Munich, Germany, the aircraft ran out of fuel. The order to bail out was given by Jones at ten thousand feet. Jones was the last to leave the aircraft. At that time the altitude was fifteen hundred feet. The only person seen by Jones prior to his bailing out was 1st Lt. William R. Joyse [sic], co-pilot, who (it was assumed by Jones) had accounted for the crew. Jones stated that he does not know how many of the crew were checked by the co-pilot even though it was the co-pilot who called his attention to the low altitude and to the fact that all of the crew were out of the ship. Jones further stated that he had no view of the nose wheel door, could not see anyone from the catwalk. He did notice, however, that the bomb bay was open. After his descent, approximately three hundred feet off-shore and in waist deep water in the North Sea near the Dutch-Belgian border, Jones was taken prisoner by the military and held until released as a result of being liberated by elements of the Russian Army on 2 May 1945. After leaving his aircraft, Jones did not see Stenard again. Hearsay information offered by Jones is to the effect that his German captors told him that one of the crew was drowned and another killed. No names were mentioned. Jones first learned of Stenard’s death upon his return to the United States on 24 July 1945 when so informed by his wife that she had received a letter from Stenard’s parents to the effect that their son had been killed in action.”

1Lt William R. Joyce – Co-pilot

“On 11 July 1944, target Munich, the mission was as usual until the return, approximately thirty minutes from the English Channel, when number two engine went out. Pilot feathered and we proceeded a little behind formation. A short time later, one and four [engines] went out, and the pilot ordered the crew to bail out. At the time, the aircraft was at sixteen thousand feet. The pilot and I stayed at the controls keeping the aircraft under control until about fifteen hundred feet, when I left the seat preparatory to bailing out. As I left the flight deck I looked back to the waist, and up to the nose, and saw none of the crew. Co-pilot bailed out, followed by the pilot, and both landed in the North Sea, at the border of Holland and Belgium. Upon reaching shore, both were captured by the Wehrmacht, stationed at invasion lookout posts. After capture [we] were united with navigator and radio operator. Later information indicated that engineer evaded successfully. Pilot, co-pilot, navigator, and radio operator were interned as prisoners of war. Questioning after cessation of hostilities on the continent, in England, and the United States revealed no further information as to the whereabouts or fate of the other five crew members.”

2Lt Phil Z. Cole – Navigator

“On returning from the target, we were flying at approximately 18,000 feet when Sgt. Charles E. Stenard’s oxygen supply went out. I brought him out of the [nose] turret and put him on an oxygen system in the nose. Just at that time the alarm bell rang to bail out because we were out of gas. Sergeant Charles E. Stenard, Jr. then picked up a chute and went onto the flight deck to bail out. Because of the incident regarding his oxygen, Sgt. Stenard had become highly nervous and almost hysterical.

“About a minute after Sgt. Stenard left I followed him onto the flight deck. When I got onto the flight deck Sgt. Stenard turned to me and hysterically screamed, “Lieutenant, I’ve got the wrong chute!” There are two types of army chutes, one with rings on them and the other with snaps, and the harnesses on these chutes go on a snap harness, or vice versa; inasmuch as Sgt. Stenard had a ring type harness on he could not attach the chute he had picked up). I told him to go back to the nose and get his own chute and bail out through the nose doors, which I had left open. These doors were opened by me to throw out all excess equipment in order to lighten the ship.

“I bailed out at approximately 3,200 feet. I am unable to say what happened to Sgt. Stenard, however, when interned in a Wehrmacht camp about 16 kilometers from the point of capture, a Wehrmacht sergeant told me that one of my comrades, first name Charles, had gone in with the ship. First Lieutenant John Jacob Jones, Jr., the pilot on my crew told me later that he saw a chute spilled on the flight deck as he bailed out, however, he did not see Sgt. Stenard or any of the other crew members as he bailed out.”

S/Sgt George L. Eifel, Jr. – Radio Operator

“I do not know whether or not Sergeant Charles E. Stenard, Jr. escaped from our aircraft, a B-24 named Satan’s Mate when it crashed in Holland on 11 July 1944. During our bombing mission, Sergeant Stenard flew in the nose turret, but had left his parachute in the flight deck. When our pilot warned us that our aircraft was running out of gasoline and that it was going to crash, Lieutenant Hammersmith, bombardier, accidentally spilled Sergeant Stenard’s parachute. Shortly after this happened, Stenard came back to the flight deck to get his chute. I do not know if Stenard found any other chute, but I saw him return to the nose turret section. This was the last time I saw Sergeant Stenard, for I bailed out about five minutes later and upon landing, was captured by the Germans. I did not see any parachutes from our aircraft because of an overcast. The other members of our crew who bailed out and were later captured by the Germans were: First Lieutenant John Jones, pilot; First Lieutenant William Joyce, co-pilot; Second Lieutenant Phil Cole, navigator; and Staff Sergeant Jake Lucero, engineer [sic].”

Casualty Interrogation Report of S/Sgt Jake T. Lucero – Flight Engineer

“Sergeant Lucero states that the bomber on which he was a crew member was battle-damaged and that the occupants were forced to bail out. He further states that, to the best of his knowledge, he was the first man to leave the ship and that he saw only one other parachute open. He did not see the ship crash. He states further that the people who concealed him in Holland informed him that one man had gone down with the ship but they did not know his name. Sergeant Lucero was of the opinion that it was the pilot until he returned to his old group at which time he was informed that Sergeant Stenard was the man who was killed in the crash.”

B-24JAZ-155-CO 44-40275 J4 L Shack Time

Jones’ crew brought Shack Time over from the States and flew their first three missions in this aircraft

George Eifel Letter

In March 1993, George Eifel (left) wrote a letter to Harold Armstrong, flight engineer on Crew 25, of which Otto Hammersmith was bombardier. Harold had apparently been in contact with Otto’s brother John Hammersmith, and was asking George for information on their final mission.

————————-

Hi Harold,

I received your most interesting piece of mail a few weeks ago, and, after much deliberation, figured it was about time I responded to it. I can well sympathize with Otto’ s brother in trying to learn the true facts as to what actually happened on July 11, 1944, to cause the death of his brother. Along with that, to know for sure where his body is actually laid to rest. Regarding the copy of the information document you sent me, I found it to be very interesting reading, not to mention, puzzling in some respects. I have some copies of reports stating that the nose gunner’s (Stenard) body was found burned in the wreckage of the aircraft, and that the body was buried in a local cemetery in Breskens, Holland.

I also have copies of some of the interrogation reports of some of my crew mates. These are all stateside reports of the interviews taken long after the actual date of the crash. These interviews occurred in 1945. It’s amazing how different the same story or happening is observed by different individuals in the same location. At this point, I will try to put into words, my version of the story; then you can possibly see for yourself why some of the end results are still a mystery to me, and why some of the answers will continue to elude me.

We were getting very low on fuel, Jake Lucero, the engineer was transferring fuel to separate tanks in order to keep the supply somewhat balanced. We were all warned by the pilot that our situation was getting grim, and that we should prepare to bail out at any time. Shortly thereafter, one of the engines had to be feathered, and then we started to lose altitude and fall behind the rest of the group in the formation. We were now flying in a heavy overcast when a couple more engines started to act up, it was then when we heard the bailout signal. Just prior to hearing the signal, Hammersmith had come up to the fight deck with a “spilled” parachute rolled up in his arms. He was closely followed by Charles Stenard, the nose gunner. Stenard was telling Hammersmith, “You’ve got my ‘chute, you spilled my ‘chute.”

This is going on right behind me, while I’m sending out the SOS on the radio. Jake is getting ready to open up the bomb bay doors, and the navigator, Phil Cole, is nearby. Now is when the situation starts getting hectic. The bailout signal has now been heard. Jake opens the doors, steps out on the catwalk, sits down on the catwalk and rolls out. Phil Cole follows him immediately. I had already snapped on my chute, so, after locking down the radio key, I followed them out close behind. In the interim, Hammersmith and Stenard had gone back down to the nose section to find the other chute. Prior to my bailing out, I had taken a quick look towards the waist section, and I can remember seeing nobody back there. To my knowledge, the only ones

still on board were the pilot and co-pilot, Jones and Joyce, trying to keep the plane level for the bailout. And then Hammersmith and Stenard were still up in the nose. These are the only four who I can swear were still on board.

The sad part of the whole story revolves around the “spilled” chute. Apparently Hammersmith (right) had a different hookup system than our crew did. Some chutes had rings on them and some had snaps. The opposite, of course, would be on the harness. Therefore, when Stenard’s chute was spilled, Otto’s chute was of no use to him. Consequently, he was doomed to go down with the plane, Hammersmith could have possibly had time enough to retrieve his own chute from the nose area and then bail out by the nose wheel, but I can ‘t say that that is what actually occurred, as I was already gone. When I jumped, we were in the heavy overcast yet, so I could not actually see the ground, not that I wanted to anyway. I did not wait too long before I pulled the ripcord, I could not tell how close to the ground I was. When I finally dropped below the overcast, I was still a few thousand feet in the air. I remember hearing the plane overhead for a while, but I did not see any other chutes. After a short while, I heard the plane crash, but due to the haze in the area, I did not see where the plane crashed.

I was captured immediately upon hitting the ground, although I did come close to landing on a cow before he finally moved out of the way. Shortly after capture, I rejoined the three officers who survived, Jones, Joyce and Cole. Jake had managed to escape capture by hiding out, got picked up by the underground, and returned to the base.

Over the years it has remained a mystery to me as to whatever actually happened to the three gunners in the back, in the waist section? Again, from what I have gathered only one body was found in the wreckage. Assuming the three fellows bailed out in the back; why would they all die as a result of it? Maybe they all bailed out over water and drowned? Upon recovery of the bodies, would they then be unidentifiable? According to the report of John Hammersmith, Otto was buried in a mass grave along with others who were unidentifiable. Many of the bits of information he gathered seem to be very questionable to me. By the way, you didn’t say in your letter, when you visited the grave site in the Zachary Taylor Cemetery, how many names, if any, were on the headstone, or whatever? Are there four or five bodies buried there? Are the names available? If you have that information, I’d appreciate it if you would pass it on to me.

B-24JAZ-95-CO 42-100341 J4 A Satan’s Mate

Satan’s Mate (formerly Mary Lee) was an original group aircraft.

On a flight in the Spring of 1944

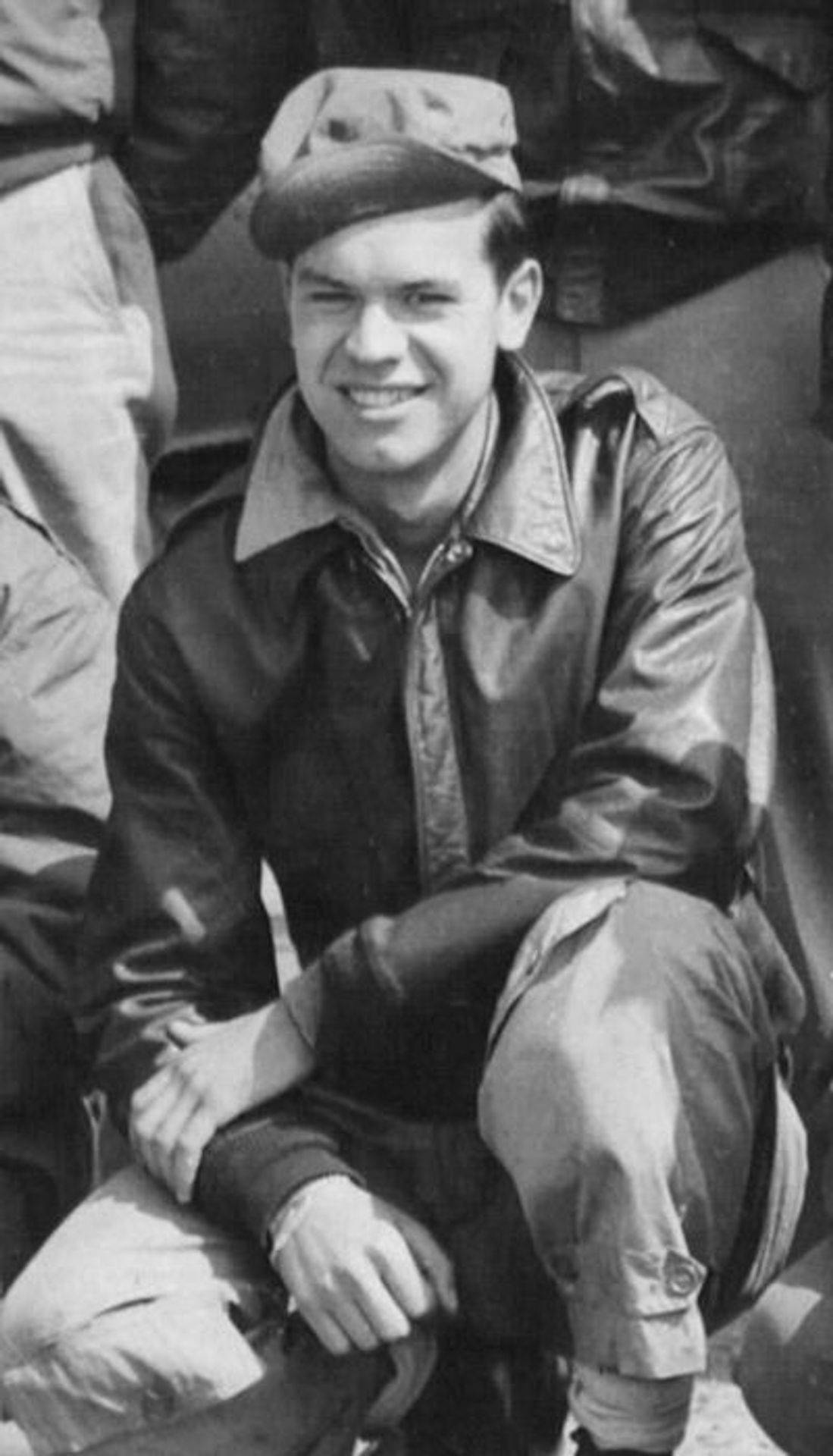

753rd Squadron Bombardiers

Capt. Richard D. Harland, Lt Gordon E. Wyman and Lt Otto B. Hammersmith at Horsham St Faith

(Photo: Anne Zimmer)

Zachary Taylor National Cemetery Plot I, 42

Courtesy: Find-A-Grave & Bobby Hunt