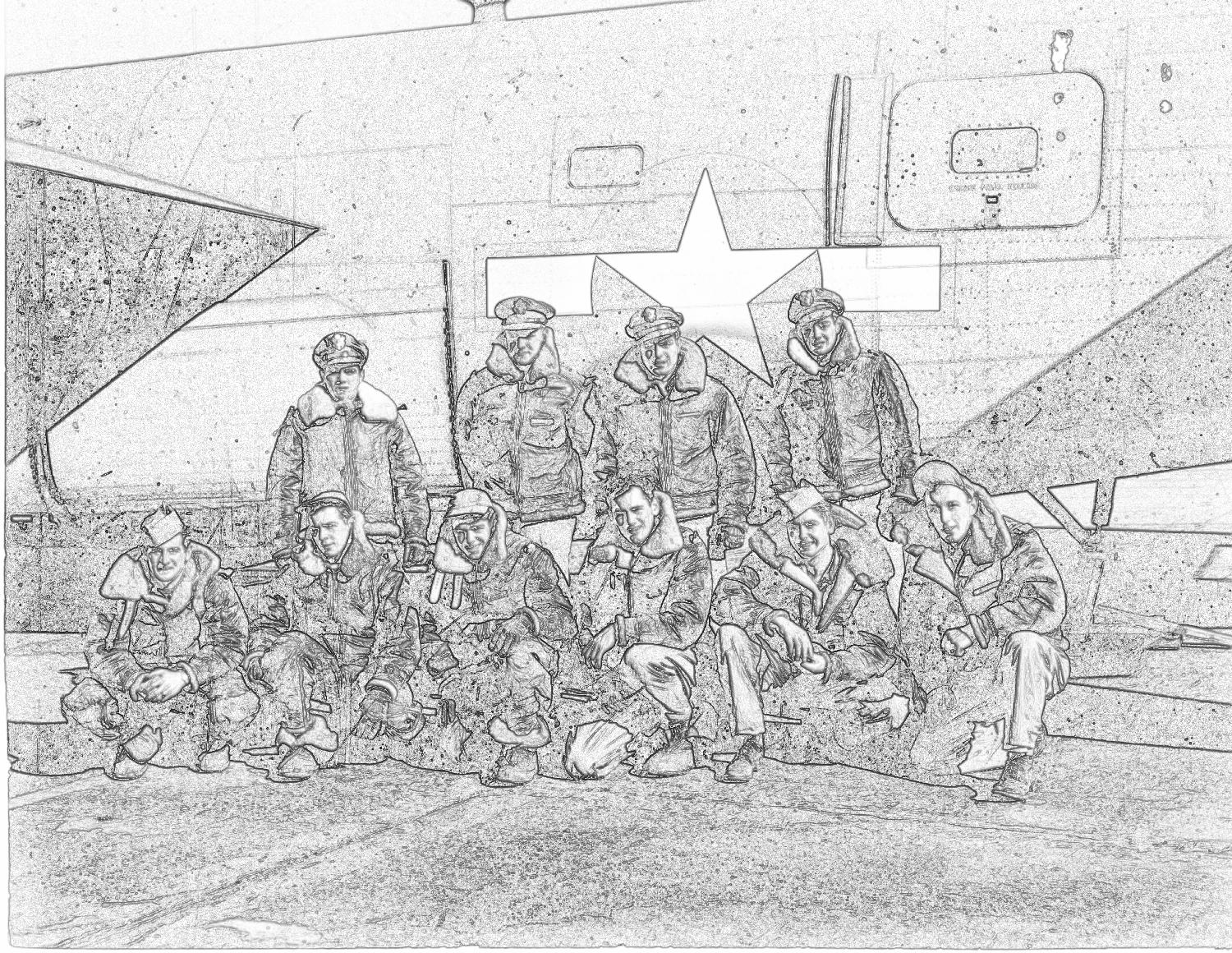

Hunt Crew – Assigned 754th Squadron – December 21, 1944

Crew Photo Needed

Mid-Air collision February 23, 1945 – AR 45-2-23-45

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Crew Position | Date | Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2Lt | Daniel F Hunt, Jr | 823592 | Pilot | 23-Feb-45 | KIA | Cambridge American Cemetery |

| 2Lt | Charles H Peckham, Jr | 834670 | Co-pilot | 23-Feb-45 | KIA | Newport County, RI |

| F/O | Ivan K Norris | T132986 | Navigator | 23-Feb-45 | RTD | Bailed out #596 |

| F/O | Norvin K Sulflow | T6923 | Bombardier | 25-Apr-45 | FEH | Pilotage Nav Snyder Crew |

| Cpl | Wallace D Lund | 37678657 | Radio Operator | 23-Feb-45 | KIA | Winnebago County, IA |

| Sgt | Henry J Hachey | 11071534 | Flight Engineer | 23-Feb-45 | RTD | Bailed out #596 |

| Cpl | Francis A Barnicle | 31304867 | Airplane Armorer-Gunner | 23-Feb-45 | KIA | Cambridge American Cemetery |

| Cpl | Michael H Diamantopoulos | 20112632 | Aerial Gunner | 23-Feb-45 | RTD | Bailed out #596 |

| Cpl | Charles P Haskins | 31296463 | Aerial Gunner | 23-Feb-45 | KIA | Bristol County, MA |

| Cpl | Jose J Luna | 38583501 | Aerial Gunner | 23-Feb-45 | KIA | Cambridge American Cemetery |

2Lt Daniel Hunt and crew were assigned to the 754th Squadron in December 1944. After a month of practice missions and indoctrination into the European Theater, they flew their first combat mission on January 28th to Dortmund, Germany. Three straight trips to Magdeburg followed, and then a mission to attack railroad marshalling yards at Peine and Hildesheim which claimed two 458th crews.

Hunt’s crew flew their sixth and final mission just 26 days after their first, to hit the marshalling yards at Saalfeld, Germany. However, due to a mix up in targets, 19 aircraft attacked the marshalling yards at Gera and 9 aircraft bombed the marshalling yards at Reichebach through 10/10ths cloud coverage. Weather over England was slightly better than over the Continent for the returning crews as the group records indicate:

“We had an unfortunate mid-air collision as our formation was over the field preparing to land. It was determined that the formation was in haze and cloud at 17,000 feet and making their first 10 minute turn over the Buncher. So far as eye witnesses could see A/C 449-W flown by Lt. R. J. BECHTEL (753rd Sq.) slid into A/C 598-R [sic] flown by Lt. D. Hunt of the 754th Sq. knocking off the left stabilizer. A/C 449-W lost a wing and both disappeared into the undercast immediately. All personnel of A/C #449 were killed, while only three men of A/C 598-R [sic] survived.”

The record keepers were in error when they stated that the aircraft Hunt was flying was 598-R. It was a B-24H, serial number 41-29596-R, named “Hell’s Angel’s“.

Ivan K. Norris, Henry J. Hachey, and Michael Diamantopoulos – navigator, engineer, and top turret gunner, all parachuted from the stricken bomber. 458th records do not indicate whether any of these three flew additional missions before the war ended.

F/O Norvin K. Sulfow, bombardier, was not on the February 23rd mission in which the collision took place. His name appears on a crew loading list for the last mission flown by the group on April 25, 1945. He is shown to be the Pilotage Navigator on 2Lt Elemuel M. Synder’s crew.

Missions

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28-Jan-45 | DORTMUND | 174 | 1 | 42-95108 | B | Z5 | 57 | ENVY OF 'EM ALL II | |

| 03-Feb-45 | MAGDEBURG | 177 | 2 | 42-51196 | Q | J3 | 32 | x x x x x QUEEN | |

| 09-Feb-45 | MAGDEBURG | 179 | 3 | 41-29596 | R | Z5 | 81 | HELL'S ANGEL'S | |

| 14-Feb-45 | MAGDEBURG | 181 | 4 | 41-29596 | R | Z5 | 82 | HELL'S ANGEL'S | |

| 17-Feb-45 | ASCHAFFENBURG M/Y | REC | -- | 42-95018 | J | Z5 | -- | OLD DOC'S YACHT | RECALL - WEATHER |

| 21-Feb-45 | NUREMBERG | 185 | 5 | 44-40298 | E | Z5 | 29 | THE SHACK | |

| 22-Feb-45 | PEINE-HILDESHEIM | 186 | MSHL | -- | -- | -- | -- | MARSHALLING CHIEF | |

| 23-Feb-45 | GERA-REICHENBACH | 187 | 6 | 41-29596 | R | Z5 | 86 | HELL'S ANGEL'S | COLLIDED w/BECHTEL |

Accident Report 45-2-23-514

DESCRIPTION OF ACCIDENT

Approximately 1527 on 23 Feb 45 B-24 449 and B-24 596, in formation with the 458th Bomb Group, collided in mid-air about ten (10) miles north of AAF Station 123. Altitude at time of collision was about 16,500 feet, visibility about 1 mile reduced to 200-300 feet in clouds.

Ship 596 was flying #3 position and ship #449 was flying #4 position ion the hole element of the second squadron. Just before the accident the element leader had aborted, and no one had assumed the lead. All ships were flying their relative position when a layer of dense clouds were entered. A few seconds later, as reported by the survivors of ship #596, another ship appeared very close just below their left wing. Almost immediately the ships came together.

The right wing of ship #449 was torn off and it evidently went into a spin immediately. the ship was destroyed by fire.

Ship #596 crashed about 1-1/2 miles from #449. It was scattered over a large area and appeared to have broken up several thousand feet above the ground.

Cause of accident 100% unknown

Recommendations: None.

————————-

754TH BOMBARDMENT SQUADRON (H)

AAF 123 APO 558

27 Feb 1945

SUBJECT: Collision of Aircraft, 41-29596 and 42-50449

TO: Air Inspector, 458th Bombardment Group

1. The collision occurred over Buncher 15 as our Squadron, second section of the Group, was making the first ten minute circle to the left to allow time interval for the first Squadron to execute proper instrument let down. Our altitude was approximately 16,500 and visibility was one-half mile in scattered clouds. The aircraft involved, [call sign] Cotstring 596 R and Fiction 449 W were flying left and right wing respectively in the slot. The slot lead, Lt. Besten left a few minutes prior due to fuel shortage. From this point, the positions of the ships in the slot is debatable. Fiction W was either flying left wing on Cotstring R or lost his position when we entered the high scattered clouds in the buncher area. Fiction W, however, did get on the inside of the formation and on endeavoring to get back into formation, overestimated his rate of closure. Fiction W’s right wing removed the upper half of Cotstring R’s left fin and definitely damaged the left elevator controls. My nose-gunner reported that Cotstring R’s entire tail assembly controls were damaged if not entirely removed. This aircraft immediately went into a steep dive straight ahead. Fiction W, however, lost the outer section of his right wing and #4 engine caught fire. He turned sharply to the right and is believed to have spun in.

2. I reported the collision on wing channel to the Squadron Leader whereby Lincoln Red Control Tower was informed.

3. The above report is as related to Sgt’s Francis Birmingham and John W. Bradley.

/Signed/

William G. Everett

2nd Lt. Air Corps

Pilot

Wreckage of #449, Heavenly Hideaway (left) and #596, Hell’s Angel’s

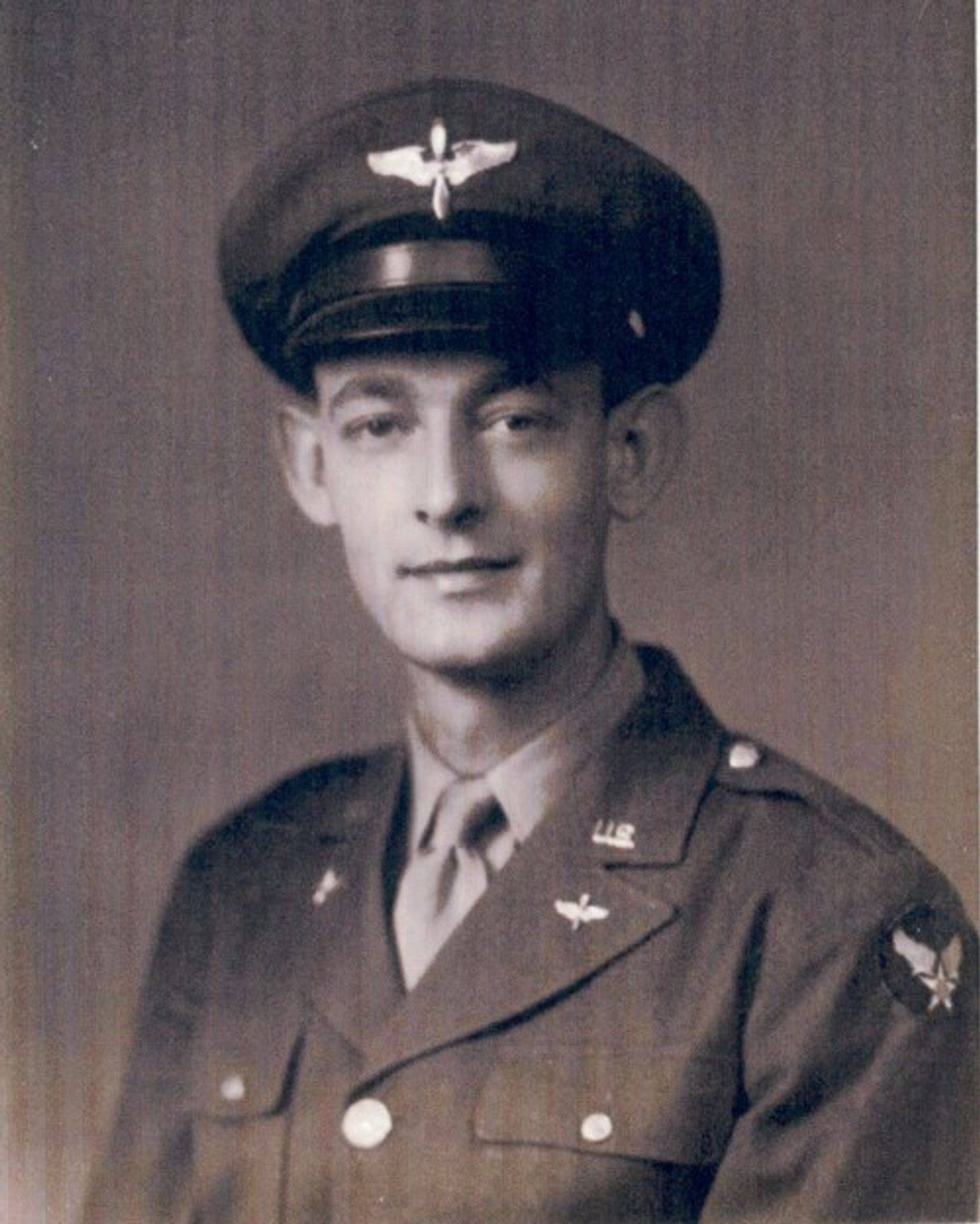

F/O Ivan K. Norris – Navigator

This day, February 23, 1945, was much the same upon dawning as the last sixty before it had been, but it was to be remembered distinctly by a few men to the end of their natural days.

The morning dawned as bleak and hazy as any of the other sixty days that we had seen since we had arrived in England as a replacement crew attached to a Liberator bomber group. We were nine men from as many parts of our great country: Dan from western New York, Charlie from Rhode Island, Henry from Nebraska, Jose from New Mexico, Chuck from Massachusetts, Norm from California, and others from places I cannot recall. We had been in England just long enough to receive our “baptism by fire”. It was my fifth mission, and for the rest it was the sixth. We belonged to a good squadron whose record for losses to all causes had been nil for almost six months. We were assigned to a good and faithful ship. “Hell’s Angel’s”, 596, had carried three crews through their tours of duty without a scratch, so we figured we could not lose.

This day we had been stirred from our slumber at [the] ghastly hour of four A.M. and had breakfast as usual about four-thirty. Yes, we had fresh eggs that morning; at least they had been fresh at one time. Briefing was about five-fifteen, but I do not recall too much of importance except a slightly more somber air than usual. On the day before, one of our crews had been crippled on a “milk run” mission, and there had been no report on whether they had gotten back to France or not. The Air Force has a superstition that trouble comes in three’s and everyone was wondering, “could it be us?”

Take-off and formation assembly were uneventful. The weather was normal for England. Cloud bases two hundred feet from the ground and cloud tops built up to eighteen thousand feet were the rule rather than the exception. I say take-off was uneventful, and yet, in one sense, it was miraculous, in view of the fact that there were three airbases within a five-mile radius, each of which was putting up thirty to forty planes in a twenty-mile circle, all with the same purpose at the same time and with a solid bank of clouds to climb through for sixteen thousand feet.

I do not remember where our target was that day. We did not see the ground again after take-off. In fact, I think the target was changed after we were in the air. It was an uneventful trip out over northwestern Germany. We saw no enemy aircraft and encountered no flak. The cloud tops had lowered over the area as we returned in formation at about ten thousand feet. I was navigator and had a small compartment behind the gun turret mounted in the nose. The nose gunner depended on me to shut him into and let him out of his turret. This particular day, he had a hole knocked in the Plexiglas shield of his turret by .50 caliber shell cases from our lead ship when they test fired guns. The nose gunner, Chuck, called the plane commander and asked to stand-by in my compartment because he was about to freeze in the draft coming through the hole in the Plexiglas. Chuck and I were beginning to relax and think about hot food and sleep that were only thirty minutes away.

We were flying a wing position in the formation, so my only problem was to follow the track of our ship. As we approached the English coast, the cloud tops moved up to about sixteen thousand feet and we started to climb to get over them. I took a radio position and found we were five miles off the English coast and headed straight for home. We were scooting through breaks in the cloud build-up. There were only minutes to go before we would be back home; then it happened.

I looked out of the window to my right and got a flash of another airplane, so close that her wing tip was almost scraping our fuselage. She was only six or eight feet below and behind us, and traveling slightly faster than we were. I grabbed my parachute from the table and at the same time yelled to Chuck, “Get out of here, we’re going to hit!”

Chuck had seen nothing at all since he was seated on a small box in the compartment, but he heard me yell and knew what I meant – without benefit of the inter-phone system. He asked no questions, but dived under my work table and opened the escape hatch. He then headed for his parachute, which hung in a crawl passage barely four feet away.

Meanwhile, I was struggling to snap the chute pack to the harness; I missed the snap on the right side. The next pass, I snapped it on, but also got a hand on the pull ring. I recall at this instant the slight crunching noise and the shudder that ran through the aircraft as the two planes collided. I recall a few seconds of level flight and then came the blackout. Apparently we must have gone into a power dive, and I was thrown against the nose turret and knocked out. I regained consciousness for an extremely short interval – long enough to see the parachute silk billowed on the floor, gathered it up, roll forward on my knees to the escape hatch, ask Chuck why he didn’t bail out – all, possibly ten seconds, and then I passed out again.

Some time later, I opened my eyes to see low scud clouds scooting by. It took fully five minutes to decide that I was still among the living, and to recall where I was and how I had gotten there. I was lying on my back in an English meadow field. There was debris scattered in the trees nearby. The wing of an airplane was leaning against a tree. Somebody’s flying boots lay near my feet; they were not mine. After a few moments, I was able to collect my wits. I decided to see if I could move. I could. After due examination I decided that I must have parachuted—there it was. During descent I had lost my helmet, heated gloves which were snapped with two snaps, nylon gloves which fit like hose, flying boots which were both zippered and snapped and had somehow inflated my Mae West life preserver. I found the pants to my flying suit ripped to shreds and later decided that I must have been dragged through a treetop.

When I finally got to my feet, I was sighted by an Englishman who was riding a bicycle along a road about seventy-five yards away. He came over quickly and asked if I were all right and then said there were some others who had “rained” down with the wreckage. He took me to a near-by country home where I was laid down to rest. The next several hours are rather hazy and of little importance. The ambulance picked me up, returned me to the base hospital, dressed my head cut where I had hit the turret, and put me to sleep.

The next morning, I awoke refreshed and sufficiently recovered from the shock to want to know what had happened and how the rest had fared. The upper turret gunner, Mike, was there and in a couple of hours, Henry, the engineer, was brought in from an English base near which he landed. We were all three intact save for scratches, bruises, cuts and sore spots. We three were all that remained of two complete bomber crews of nine men each.

The cause of the accident was never clearly determined. Weather conditions were not good, but how did we collide with the leader of the third element ahead of us in formation? Our pilots pulled up on warning from the engineer and in so doing snapped the wing off the other plane and damaged our vertical stabilizer. After that, all that remained was a short, quick trip to the ground below.

Courtesy: Francis Norris

Artwork & Photos – Mike Bailey

B-24H-15-CF 41-29596 Z5 R Hell’s Angel’s and B-24H-30-CF 42-50449 J4 W Heavenly Hideaway

Flare pistol and flak helmet from one of the a/c involved

Courtesy: City of Norwich Air Museum (CNAM)