Crew 50 – Assigned 754th Squadron – October 1943

Standing: Richard Moses – N, Robert Ahrens – B, Jake Couch – CP, Teague Harris – P

Kneeling: Unidentified, Maurice Kahl – TG, Unidentified, Gilford Oder – RO, Eldridge Carpenter – TTG

If you can identify anyone in this photo, please contact me.

(Photo: AFHRA)

Shot down by Night Fighter Intruder April 22, 1944

| Rank | Name | Serial # | Crew Position | Date | Status | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2Lt | Teague C Harris | 026132 | Pilot | 22-Apr-44 | WIA/RFS | Wounded - Removed from Flying Status |

| 2Lt | Robert T Couch, Jr | 0672335 | Co-Pilot | 22-Apr-44 | KIA | Cambridge American Cemetery |

| 2Lt | Richard L Moses | 0810110 | Navigator | 22-Apr-44 | KIA | Cambridge American Cemetery |

| 2Lt | Robert A Ahrens | 0734293 | Bombardier | 01-Jul-44 | CT | Awards - Distinguished Flying Cross |

| S/Sgt | Francis X McKenna | 13153383 | Flight Engineer | 22-Apr-44 | KIA | Philadelphia County, PA |

| Sgt | Gilford L Oder | 34407107 | Radio Operator | 22-Apr-44 | KIA | Gilchrist County, FL |

| S/Sgt | Howard E Found | 37493308 | Nose Turret Gunner | 22-Apr-44 | KIA | Lee County, IA |

| S/Sgt | Eldrige L Carpenter | 1410304 | Top Turret Gunner | Mar-45 | CT | Trsf 70RD Return Zone of Interior |

| S/Sgt | Fernand G Morin | 11128009 | Ball Turret Gunner | 22-Apr-44 | KIA | Belknap County, NH |

| Pvt | Maurice W Kahl | 17068342 | Airplane Armorer | 01-Feb-45 | RFS | Promoted to Pfc |

Harris’ crew trained in Tonopah, Nevada in 1943 and flew the Southern Route to the ETO with the 458th Bomb Group in January 1944. Prior to flying in combat 2Lt Robert T. Couch, co-pilot took over as pilot of Crew 51 from 2Lt Robert L. Mundowski. It is not known who replaced Couch as co-pilot on Harris’ crew. Tail turret gunner Sgt Maurice W. Kahl was also replaced by Sgt Edwin B. Carpenter. The crew now had two gunners named Carpenter – Eldridge and Edwin.

The crew flew their first mission, a non-credited sortie, on February 24, 1944. This was in support of the Eighth Air Force’s “Big Week” – the 458th flew a diversionary mission to the coast of Holland in the hopes that the Luftwaffe would be drawn away from B-17’s and B-24’s attacking targets in Germany. It would be another 24 days until they flew their first combat mission on March 18, 1944, a rough mission to Friedrichshafen, Germany, made more difficult by towering cumulus clouds that lay before the target. Eight missions (including one abort) followed leading up to the April 22, 1944 mission to the marshalling yards at Hamm, Germany. In a somewhat rare occurrence for 458th crews all of the Harris crew’s combat missions were flown in the same aircraft. On this day, they once again took off in ship #353 and this time Harris had his old co-pilot, Robert “Jake” Couch back in the right-hand seat, as they were short a co-pilot, and Couch was not scheduled to fly with his crew.

Trailing the 2nd Bomb Division, the 458th lead ship in the first section had navigational difficulties and was forced to head for the secondary target at Koblenz. Harris’ crew was one of twelve 458th B-24s in the second section to drop their bombs on the primary target at Hamm. Approaching the coast of England after the sun had set, Luftwaffe night fighters took advantage of the gathering darkness and swept in among the B-24’s of the 2nd Division. Two aircraft from the 458th, 1Lt Charles W. Stilson’s of Crew 54 and Harris were shot down near Horsham St Faith.

(See detailed accounts below & 458th BG Report to Gen Spaatz).

Three men, 2Lt Robert Ahrens, bombardier, S/Sgt Eldridge Carpenter, top turret gunner, and Sgt Edwin Carpenter, tail turret gunner managed to bail out before ship #353 crashed. 1Lt Teague Harris was still at the controls when the crash occurred. Rescuers found him and removed him from the scene. He would survive after a lengthy stay in the hospital. Six men, including “substitute” co-pilot “Jake Couch” were killed in the crash.

Robert Ahrens and Eldridge Carpenter would go on to complete their tour of combat missions in the 458th later that summer. Carpenter was also awarded a Purple Heart in May for wounds received on the Hamm mission. He apparently went on to fly an additional tour of missions in the 755th Squadron. His name is listed in that squadron’s records in March 1945 as completing a tour of missions and being reassigned to the Zone of Interior (ZI).

Edwin Carpenter’s wounds also earned him the Purple Heart, but his right hand was severely injured and he would fly no further combat missions. After three months in the hospital he was sent to the 448th Bomb Group where he served as a ground crewman until the end of the war.

Missions

| Date | Target | 458th Msn | Pilot Msn | Serial | RCL | Sqdn | A/C Msn | A/C Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-Feb-44 | DUTCH COAST | D1 | -- | 42-52450 | -- | Z5 | D1 | UNKNOWN 032 | Diversion Mission |

| 18-Mar-44 | FRIEDRICHSHAFEN | 9 | 1 | 42-52353 | J | Z5 | 7 | UNKNOWN 049 | |

| 21-Mar-44 | WATTEN, near ST. OMER | 10 | 2 | 42-52353 | J | Z5 | 8 | UNKNOWN 049 | |

| 22-Mar-44 | BERLIN | 11 | 3 | 42-52353 | J | Z5 | 9 | UNKNOWN 049 | |

| 05-Apr-44 | ST. POL-SIRACOURT | 16 | 4 | 42-52353 | J | Z5 | 13 | UNKNOWN 049 | |

| 08-Apr-44 | BRUNSWICK/WAGGUM | 17 | 5 | 42-52353 | J | Z5 | 14 | UNKNOWN 049 | |

| 09-Apr-44 | TUTOW A/F | 18 | ABT | 42-52353 | J | Z5 | -- | UNKNOWN 049 | COULD NOT FIND FORMAITON |

| 10-Apr-44 | BOURGES A/F | 19 | 6 | 42-52353 | J | Z5 | 15 | UNKNOWN 049 | |

| 11-Apr-44 | OSCHERSLEBEN | 20 | 7 | 42-52353 | J | Z5 | 16 | UNKNOWN 049 | |

| 13-Apr-44 | LECHFELD A/F | 21 | 8 | 42-52353 | J | Z5 | 17 | UNKNOWN 049 | |

| 22-Apr-44 | HAMM M/Y | 25 | 9 | 42-52353 | J | Z5 | 19 | UNKNOWN 049 | SHOT DOWN INTRUDERS |

Excerpt from “Night of the Intruders” by Ian McLachlan

Night of the Intruders

First-hand accounts chronicling the slaughter of homeward bound USAAF Mission 311

The following account of Crew 50 on April 22, 1944 is from Night of the Intruders by Ian McLachlan, who very kindly granted permission to duplicate certain portions of his book detailing the loss of 458th crews on this website.

Establishing lists of killed and missing airmen proved impossible immediately after the attack because many ships landed away from base, either deliberately or in desperation. Having warned his 458BG about the likelihood of intruders, Colonel Isbell now anxiously awaited his group’s arrival at Horsham St. Faith. “After dinner that evening, Colonel House and I went for a drive around the aerodrome. At dusk we stopped at Flying Control to wait for the mission’s return. Standing on the balcony, we watched other elements of USAAF bombers as they descended towards their home base. We recognized the 458th still a good 20 miles to the east – no lights showing but the forward passing lights. They were further recognized for the excellent and close formation they flew (I had a fetish about their returning from a mission in a prideful way because I saw so many other outfits with stragglers and that looked like they had taken a licking). As we watched, the fireworks began, 20 mm cannon! I knew what it was. I ran inside, took the mike and gave the alert. Runway lights, approach lights, everything visible was put out. Then we watched two aircraft go down.”

Co-piloting one of those aircraft was Second Lieutenant Robert T. Couch, Jr. “Jake” Couch had originally been assigned as co-pilot to First Lieutenant Teague G. Harris, Jr. before being given a crew of his own. Finding them not scheduled for Mission 311, Jake volunteered for a vacant co-pilot’s slot with his old crew. Like many Americans, Jake had been “adopted” by a local family, Les and Vi Murton, and spent many hours relaxing in their Norwich home. Les had flown in the First World War and knew domestic normalities could alleviate combat stress. In the few weeks since Jake arrived, the Murtons’ fondness for the young flier had grown and a bond developed between his family and theirs which spanned several decades. Jake had married shortly before coming overseas but the pace of training had given him only three weeks with his bride, and now he was cramming missions in to complete his tour early and rejoin Judy. The Murtons understood this but worried about the number of operations he was flying and Vi became increasingly apprehensive whenever the bombers trembled the window panes of her home near the airfield. Jake, imbued with youthful exuberance, continued taunting fate.

Wreckage of Harris’ ship 42-52353 J Z5

Photo: Night of the Intruders

On the southwestern side of Norwich, near the Tuckswood Inn, other rescuers found a badly-burned pilot amid the debris of his bomber. His back was broken but Harris would recover after months of hospitalization. Jake, his co-pilot, had been almost cut in half during the crash and died instantly, along with five other airmen. By strange coincidence, their bomber had fallen on land belonging to Vi Murton’s father and now part of a school playing field. The following day, the news was broken to the Murtons, along with a request that they say nothing to Jake’s family for 30 days. Letters expressing their love and sharing hopes for his future sat unanswered until the grim bureaucracy of war caught up. Les and Vi Murton never forgot the young American whose life they briefly shared and always cherished.

Other East Anglians would always remember witnessing the events that cost Jake and many others their lives. Mr. H. L. Pittam, then resident in Poringland, saw a Liberator attacked.

I was on leave that night from the RAF and, as there were no air raid sirens in the district, the only warning was the alarm bell of the light AA units guarding the radar station at Stoke Holy Cross. I went outside on hearing the bell and could see some searchlights and scattered AA fire over Gt Yarmouth. My next door neighbour, an air raid warden, said the Yanks had gone out that day and weren’t back yet, but I didn’t link the two. I could hear the bombers coming in sounding very heavy and I knew from past experience that the Americans weren’t trained to night operations in the air.

It was a sort of half lit sky and a Liberator flew over going north towards Norwich. He was at about 500 feet and I knew he was in the landing pattern for perhaps Seething. Suddenly the tail gunner opened fire, just as a fighter flew over behind him. It was twin-engined and I thought it was an Me110. They were now firing at each other with tracers and cannon hitting each aircraft. Then the tail gunner stopped firing and I supposed he had been hit.

A small red glow appeared under the port inner engine and slowly got brighter as the Liberator flew steadily on towards Norwich. Meanwhile, as the fighter turned to starboard, the mid-upper gunner fired and the .5s tore into the underfuselage of the fighter which turned away, still to starboard and flew slowly northeast towards Framham Pigot with engines banging and surging. He was, or appeared to be, losing height when I lost sight of him heading away.

The Liberator meanwhile flew on but now all the port wing was ablaze and he seemed to slip behind the trees on the hill. I wondered then if he would drop on Norwich. Overhead, I could see the shapes of bombers literally flying in all directions and suddenly the sky was lit up with tracers again as aircraft fired at each other. I could not detect any fighters in the melee but as I watched, I could see that the tracers were from bombers and I realized that the Liberators were firing at each other! As the noise decreased and the bombers diverted to other airfields, I counted 12 big fires in the area around me for a distance of some miles, with the faint popping as ammunition exploded in crashed aircraft. There was no all-clear from the AA site and the silence was very deafening.

Whether Mr. Pittam saw the Harris ship attacked is inconclusive because both the tail and top turret gunners perished and no claims were made. However, Sergeant Lewis Brumble [pictured at right, kneeling, center], left waist gunner on the aptly named, Last Card Louie, flown by First Lieutenant H. W. Wells, was given credit for the destruction of an Me410 from 6,000 feet at 2230 hours. The Combat Form completed during interrogation reads, “As aircraft was returning to base after missions, enemy intruders attacked around 2215 in darkness.

One Me410 made a pass from 2 o’clock high, circled and attacked again. Aircraft was not in any set formation and gunners were all on alert for return of enemy aircraft. When southeast of Rackheath airdrome, Me410 came in again from 2 o’clock low and passed below aircraft 441. Left waist gunner fired at least 100 rounds, tracer hitting behind pilot’s compartment as enemy aircraft passed beyond (our) aircraft. Enemy aircraft fell on right wing and dove straight into the ground on fire. Large explosion when he hit the ground”.

A 389BG Liberator also claimed the destruction of an Me410 in the same area but of two Me410s lost that night, only one was confirmed. Ron Cain of Bergh Apton had been indoors listening to the radio when the drone of many aero-engines drew him outside to observe the spectacle of Liberators landing at night. Watching, he saw a twin-engined aircraft closing in on a B-24 and tracers flashed like an assassin’s dagger. Simultaneously, one of the bomber’s waist guns struck back hitting the intruder which burst into flames. Engines screaming, it dived steeply to oblivion and exploded in a field at Ashby St. Mary.

Visiting the scene very early next morning, Ron saw a large crater surrounded for some distance by scattered unrecognizable debris, but one of the pieces he picked up was marked “Me410”. The nose and engines were buried and young Ron saw a parachute pack amid the wreckage in the hole and, hoping for a prize his chums would envy, he clambered down over lumps of disgorged earth. Reaching his intended trophy, Ron was disappointed to find it so scorched that it disintegrated at the slightest touch, and he scrambled clear in search of other mementoes. Meanwhile, his father, Walter Cain, on duty with another Home Guardsman, had the grisly chore of collecting human remains mingled amidst pieces of aircraft. It was a task not for the squeamish. The two men wandered the field using their bayonets like park-keepers, transferring what they found into sacks. During this somber process, Walter Cain found a wallet containing quite an amount of Dutch currency and handed it in to the authorities. Ron was a little less forthcoming with is next find. An unusual feature of the Me410 was its two remotely-operated, rearward-firing 13 mm MG131 machine guns in barbettes on either side of the aft fuselage. Near the edge of the field, Ron found one of these, bent but a superb souvenir, so he surreptitiously dragged it into the undergrowth for later retrieval. Unfortunately, when the time came, it had vanished, apparently found by the RAF recovery team who arrived later that morning. They also recovered the cockpit canopy which had fallen with a flying helmet some distance from the main site, suggesting that the crew had attempted to bale out. At first, only the pilot, Oberleutnant Klaus Kruger could be identified, presumably because of his wallet. His radio operator, Feldwebel Michael Reichardt was not traced until later. Their aircraft, coded 9K+HP, werke number 420458, yielded “no new information” to British Intelligence, nor were the Allies aware that II/KG51 had lost a second aircraft in action over England. Uncertainty surrounds the disappearance of 9K+MN, werke number 420314, because no trace of it has ever been found. Whether it vanished unseen into one of the region’s many broads or, more likely, disappeared limping homewards over the North Sea after sustaining damage is unlikely ever to be known. Its loss was significant because its pilot was the staffel commander, Major Dietrich Puttfarken, along with Oberfeldwebel Willi Lux as his radio operator.

Adding to the confusion, a contemporary 458BG public relations press release credited 2Lt Charles W. Stilson’s gunners with destroying their attacker. More credence can be given to the Silver Star subsequently presented to Stilson for his courage. Years later, another 458BG flier, Glenn R. Mattson, confessed to his own comparative lack of heroism that night. Writing in the Second Air Division Newsletter, Glenn recalled, “22 April 1944 was a stand down day for our crew so we did not have to fly. . . I sat around all day. Went to Dome trainer for a while and got bored. I decided to get a pass and go to Norwich. It was refused. I said to hell with them and went AWOL. I got dressed and went out the Burma Road. As usual I got all drunked up. Some English sailor sold me a bottle of some very bad booze, bathtub type. At about 10.30 at night, I am staggering along a ditch at the end of the runway when I heard the darned awfullest noise. Couldn’t believe what I was hearing, It was anti-aircraft guns going off all around me. Out of the dark came this B-24 roaring down the runway and over the top of me. Pursued by a Ju88 or a Me110. Jumping for the ditch, I lay there for awhile until it quieted down. I took off for the debriefing hut with my bottle of booze. I got there as the crews were coming in. These guys looked like ghosts, pallid and drawn and scared from their dreadful experience. One guy came in carrying his popped parachute. He looked like he could use a drink, so I offered him one from my bottle. That was the last time I saw that bottle. . .”

A more sober view of events is offered by 458BG pilot, Captain John L. Weber. “We were on a long final approach to Horsham, gear and flaps down, when tracers started coming from behind us, passing on below and going on ahead. I yelled over the intercom to Callahan, the tail gunner, ‘Do you see a fighter back there?’ He came right back with, ‘Yeah, I see him’. I hollered, ‘Why aren’t you firing?’ He came back with, ‘I’m waiting for him to get in range.’ With that, the entire crew came on the intercom laughing and yelling for Ray to start firing. About this time the runway lights went out and the tower advised everyone to disperse and try to shake off the fighters. We went up the Wash and circled until things quietened down, then came back to land.

“My next recollection is of standing at the bar in the Combat Crew Mess when ‘The A-rab’, who if my memory is correct was Lieutenant Stilson’s co-pilot, Lieutenant Worton, came in the door dragging his open parachute behind him. As I remember, we had a difficult time getting him to leave the bar and report in to his squadron. He had baled out at low altitude and it had taken him quite a long time to find his way home in the dark.”

To sooth nerves still jangling, a late night movie, Going My Way, was organized and number of combat crewmen soon found themselves absorbed in the story of Bing Crosby as a crooning Irish Priest overcoming gentler adversities in his New York parish. As his Group settled, Colonel Isbell took stock. “We stood to lose 26 aircraft that night, each with at least 10 members aboard. We lost only two aircraft and nine men. It was a miracle that we only lost nine of the 20 on board these aircraft”.

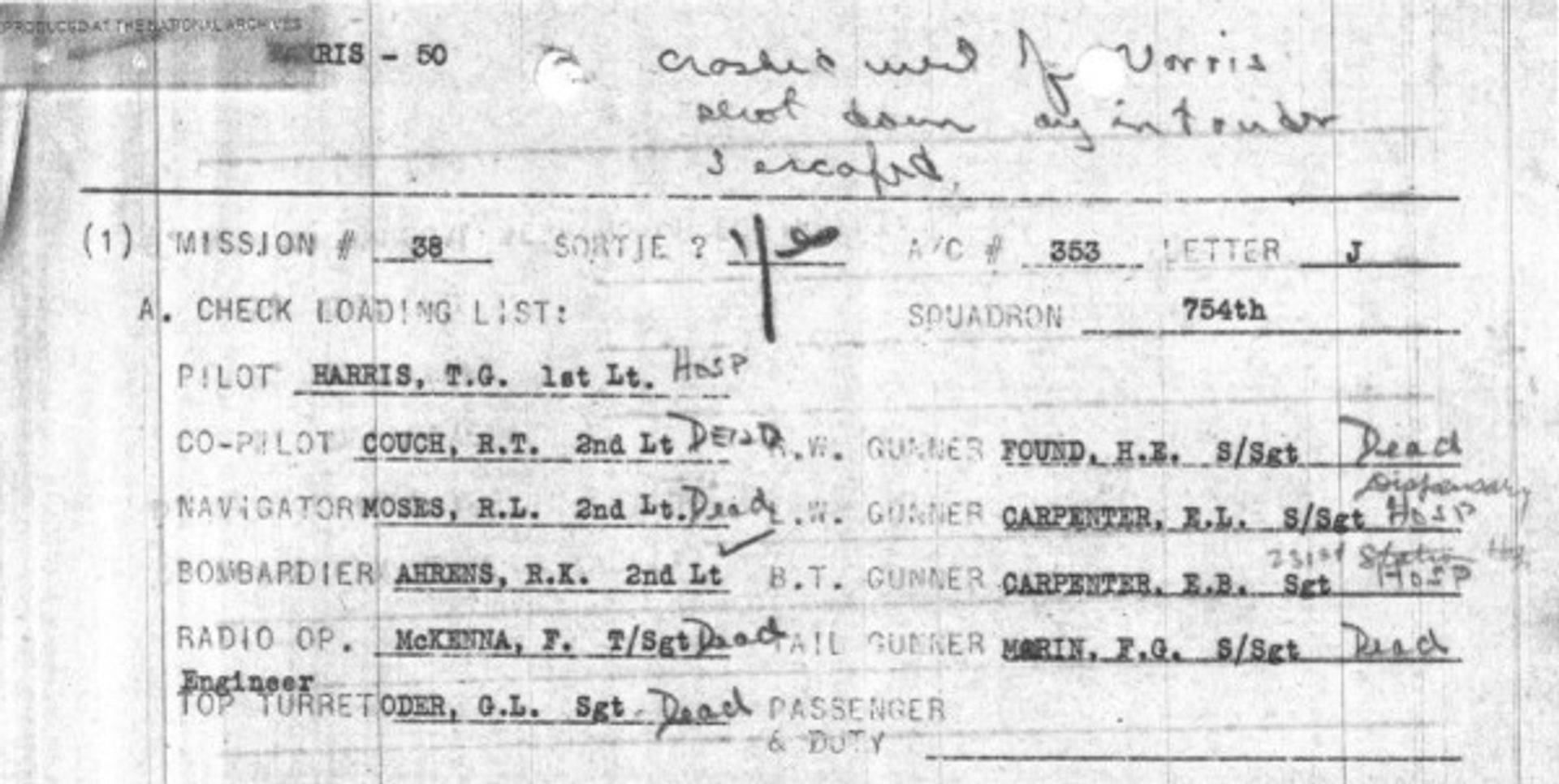

Crew 50 Loading List April 22, 1944

Sgt Edwin B. Carpenter

The following was recorded during an interview with Edwin Carpenter’s granddaughter Katie. It was transcribed exactly as recorded and is reproduced here with the kind permission of the family.

Edwin B. Carpenter (Courtesy: Barbara Todd)

“On the 22nd of April 44, the 10th mission which was my last mission, the whole 8th Air Force target was Hamm, Germany which is one of the largest railroad marshalling yards in all of Europe. The thing unique about this mission, we didn’t take off from England until about 4:30in the afternoon and got over the target around 6:00 or 7:00 at night and then by the time our group got over the target we were one of the last to hit it. Smoke was already at 25,000 feet so there was quite a bit of confusion over the target due to the obstruction of the target. Although we successfully dropped our bombs and headed home for England as we approached the English Channel we could see the rockets being fired from the ground up at our formations. Then over England proper it was dark by then around 10:30 at night.

“Unbeknown to us, the English started firing anti-aircraft fire at our formations but we didn’t know that there were German night fighters in our formations. So as a result of not being able to see and know what was going on, our plane was shot down by a German fighter which proved later to be an ME110 fighter. [These were actually ME410 Hornets from II/KG1]. At that time three of us were able to parachute out of the plane, and seven of the crew were still aboard the plane when it crashed including my pilot 1st Lt. (now Col. USAF Ret) Harris.

I did not contact any of these crew members until some 51 years later I located 1st Lt Harris in San Antonio, Texas and he thought at the time of the accident that my arm was shot off. The injuries I sustained were minor injuries to the head and heavy damage to my right hand. I was picked up by an English farm family, transported back to my base by ambulance and from there the next day I was transferred to the 231st General Hospital. I was in the crash ward for 24 hours, underwent surgery on my right hand and about a week later I was shipped to the 65th General Hospital for rehabilitation. After spending 93 days in the hospital, I was shipped to Leeds, England to a replacement depot. Not knowing whether I could continue flying or not due to my accident, it was decided to send another fellow and myself to the 8th AF Bomber Command which was outside London at High Wycombe. He and I made this journey down there and back and met with the medical board and it was decoded there that I could no longer fly. So I was sent back to the replacement depot and was assigned form there to the 448th Bomb Group as a ground crew member. I remained there until the end of the war, in the 448th.

I did not contact any of these crew members until some 51 years later I located 1st Lt Harris in San Antonio, Texas and he thought at the time of the accident that my arm was shot off. The injuries I sustained were minor injuries to the head and heavy damage to my right hand. I was picked up by an English farm family, transported back to my base by ambulance and from there the next day I was transferred to the 231st General Hospital. I was in the crash ward for 24 hours, underwent surgery on my right hand and about a week later I was shipped to the 65th General Hospital for rehabilitation. After spending 93 days in the hospital, I was shipped to Leeds, England to a replacement depot. Not knowing whether I could continue flying or not due to my accident, it was decided to send another fellow and myself to the 8th AF Bomber Command which was outside London at High Wycombe. He and I made this journey down there and back and met with the medical board and it was decoded there that I could no longer fly. So I was sent back to the replacement depot and was assigned form there to the 448th Bomb Group as a ground crew member. I remained there until the end of the war, in the 448th.

“Okay, I’ll give a little more detail on this last mission I flew on the 22nd of April 44 to Hamm, Germany. This was the first mission that the 8th Air Force had flown when we were to return after darkness. On the way out of the target that day, after being severely beat up with flak, coming out over the coast of Holland you could see the rockets which were the first ones I experienced as they were fired from the ground you could see them all the way from the ground into the formations and the huge explosions form the flak. Approaching the English coast near Great Yarmouth, England which is about 20 miles from home base in Norwich and me being in the tail turret facing aft notices several planes in flames going down over the North Sea. I figured they were going down as a result of the rocket attack on the way out of Holland.

“As we came into the pattern to land, all of our identification lights [were] on to try to notify the English to quit shooting and little did we know that there were German fighters among our formations. All at once I distinctively remember the enormous explosion that hit our aircraft. I was in the tail turret at the time. The explosion blew me backwards up into the waist section of the aircraft. I later learned that the [tail] turret was found around 10 miles from the aircraft wreckage…so lucky me I went backwards instead of off the aircraft. In the scramble to get my parachute, I buckled it on since it was a chest type, I had to open an escape door that had a heavy K21 camera mounted on it. I managed to get it open and jump. At the time I didn’t know altitude or anything, I did know that the aircraft was one white ball of flame and I was leaving any way possible.

“As I jumped, I distinctively remember pulling my ripcord with my left hand, it was supposed to be a right hand pull, but at the time I had all the bones in the back of my hand broken from shrapnel. I landed in an English sugar beet field. A young man came out and assisted me in getting out of my parachute harness and helped me into his house. I didn’t know the nature of my wounds until I arrived in a base hospital and was examined by a Flight Surgeon and from there it was decided that I would go to a general hospital for surgery.

“At the time I thought I was the sole survivor of ten people on board this aircraft, but later on I found out that four of us survived with my pilot being the most severely injured since he crashed with the airplane. I found this information out in 1995 when I eventually located him after 51 years. He advised me that when he went down with the plane and crashed the next thing he knew he came to in a morgue with a sheet over him. They had put him in a morgue for dead and he came to. And he tells the story to me that he (chuckle) was very lucky to have gotten out of the morgue and got back into the hospital.

“After arriving at the 448th Bomb Group in England, I became the Assistant Crew Chief of a B-24 aircraft. I worked on this airplane for 13 months before the war ended. This plane that we worked on flew 96 successful combat missions with only two Purple Hearts awarded during the 96 missions. This plane was a war-weary plane and had four missions left before it would have been retired to the bone yard that is, scrapped. The way it was we had to make this plane ready for a flight across the Atlantic back home after the end of World War II. The war with Germany ended on the 8th of May 1945 and from that day forward we did maintenance on our aircraft in preparation for a flight home to the USA.”

2Lt Richard L. Moses – Navigator