458th Bombardment Group (H)

A Trip to Germany

On 6 March 1945, two days after our Second Division bombers led by the lost lieutenants from Wendling dumped on Zurich and our Attlebridge Wing neighbours pasted Basel, the American Armies captured the Rhine Bridge at Remagen. Our ground troops crossed into the heart of Nazi Germany. We could see the end coming soon in Europe. When Major Chuck Booth was Assistant Group Operations Officer, we saw little of him except at briefings, which he conducted with great class. He didn’t come around to the navigation office to ask pertinent questions or to bug us, he left that to Colonel O’Neill. But now that Major Maurice Speer [left] had replaced Booth, we saw him frequently. He apparently believed in close co-ordination with the Group Navigator and Group Bombardier, for Speer was always popping into the office, if only to wish us well.

Shortly after the Americans secured the Rhine crossing at Remagen, a request came into Headquarters for the 458th to transport an Eighth Air Force liaison officer. The Signal Corps had people who kept radio beacons at (or sometimes ahead of) the front lines. Our lead ships could receive the signals from these beacons and (hopefully) drop bombs only beyond them, even on targets of opportunity. Eighth Air Force kept a knowledgeable officer, usually a pilot, with the Signal Corps on the continent to advise about beacon placement and other matters related to strategic bombing. The man currently on duty in Europe was scheduled for rotation, so we were asked to take his replacement in, and bring the rotating officer out.

The TWX carrying our personnel transport order came across the desk of Major Maurice Speer. He came running into my office.

“Granholm,” he said, “how about a trip to Germany?”

“What?” I said, “What for? I’ve already been there.”

“This trip is different.”

Speer showed me the TWX. “I’ve assigned myself as pilot. I’ll put you down as navigator if you like.”

“Let’s go,” I said.

General Peck, among the various aeroplanes suited to his exalted rank, had a Norseman. This ship was a single-engined, high-winged monoplane built in Canada for puddle-jumping and bush-piloting. Speer arranged to borrow it for our tour to Germany.

The day following, our replacement liaison officer showed up at Horsham, and the three of us loaded our baggage into the Norseman. Since we did not know what we might find in recently occupied Germany, Speer and I each carried our John Roscoe 45-calibre automatic pistols. I also checked out and loaded aboard a Thompson sub-machine-gun -a “Chicago tattoo machine” -just in case. Having loaded all our essentials, we took off into the afternoon.

We got up early the next morning and went out to the air-base. Everything looked fine, so we took off in our little puddle-jumper, headed for some obscure destination in Germany called Bruhl, which was where we were to deliver our liaison officer.

Bruhl is a suburb, a wye in the railroad, about ten miles south of Cologne. It was alarmingly close to the Rhine, and the German Army was just on the other side of that river. At least, we hoped they were all on the other side by the time of our arrival.

When we arrived at Bruhl there were farms and green pastures all around, but no airfield. We checked the maps and the orders. This clearly was where we were to go, but where were we to land? Speer circled the place about five times. Each time he flew on the Rhineward side of Bruhl, I yelled at him to look inconspicuous. I expected a flak shell through the Norseman momentarily, remembering how well panzer troops could shoot at aeroplanes.

Finally we gave up. We went west again till we found an impromptu airfield out in the boonies which had P-38 fighters parked all over it. It had to be a Ninth Air Force operation so we called the tower, and came in to land.

The whole airbase was made of pierced steel track. This remarkable material, laid on the local mud, made runways, taxiways, and aeroplane stands for a whole tactical fighter group. It was the bright idea of some inventive genius.

We asked how to find the airfield at Bruhl. Nobody knew, so they took us to their leader. The commanding officer of the P-38 outfit was a light colonel. He was in his command tent with his mess kit out, just ready to eat lunch. He invited us to have lunch with him and we accepted. It was good chow, served up on a G.I. tin plate. I commented to the colonel that our information was a little out of date so his steel airfield was not shown as an emergency landing opportunity for a B-24 in trouble. I said that I intended to add it to my navigators’ lists of good places when I got back to Horsham.

“Don’t bring any of your —dam bombers in here!” the colonel said. “They’ll mash my track so deep we’ll never be able to dig it out. We’d have that big ugly mother—— stuck in the mud here forever. I’ll shoot the son-of-a-bitch who brings a B-24 in here!”

The colonel told us that the place we were expected to land our Norseman was a green cow pasture just to the south-west of downtown Bruhl, and he drew us a little map of the correct pasture on a page of his notebook. He said that if we looked closely, we would see that some thoughtful person had stuck up a windsock alongside the fence.

After lunch we went back to our Norseman. We had to sit there for a while. A bunch of P-38s were landing from a strafing mission. They were taxying, each to its assigned steel parking area. A G.I. mechanic was walking towards us along the steel planking, carrying his mess kit. He stepped off the plank taxiway to avoid a P-38 taxying towards him. There was a sudden sharp explosion. The G.I. had stepped on a land mine – a booby trap – one of many left behind by the retreating Germans in their thoughtfulness. The kid’s leg was blown off above the knee.

The medics were with him in an instant, hauling him off to the field hospital. I exercised skill to keep from vomiting at the sight. We had walked down the same steel planking ten minutes previously. I hoped that the land mine victim would survive, but I knew it would be quite a while before he walked again.

A bit shaken, we fired up the Norseman, and took off when the runway was clear. We found our cow pasture at Bruhl and landed, more or less expertly. But taxying was a problem. The place was very muddy.

We found our Signal Corps people and got a jeep ride downtown where we found quarters and bunked in for overnight. That evening, we discovered, there was a movie to be shown at the G.I. theatre, appropriated by the Americans for the purpose in downtown Bruhl. Speer and I decided to go and watch Jimmy Stewart, or whomever, on the silver screen.

Colt Model 1911 .45 Cal Automatic

Thompson M1928 Sub-Machine Gun

My John Roscoe 45 automatic was government issue for all flying officers. It came with a shoulder holster, just like the ones worn by Capone torpedoes, but I shortened the strap and wore it on my hip, like Gary Cooper or Tom Mix would have done. We were walking down the main street of Bruhl at dusk when I sensed an upstairs window open opposite us. Thinking immediately of a German sniper, I pushed Speer into a doorway. I had (fortunately) left the Thompson gun under the bed in our quarters, so I unlimbered my John Roscoe. Across the street was a pretty girl, hanging her sweater out to dry on the window shutter.

The girl did not know the frightful danger she was in. Of course, my expertise with the John Roscoe was such that I could never have shot her, but I surely would have hit the building she was in.

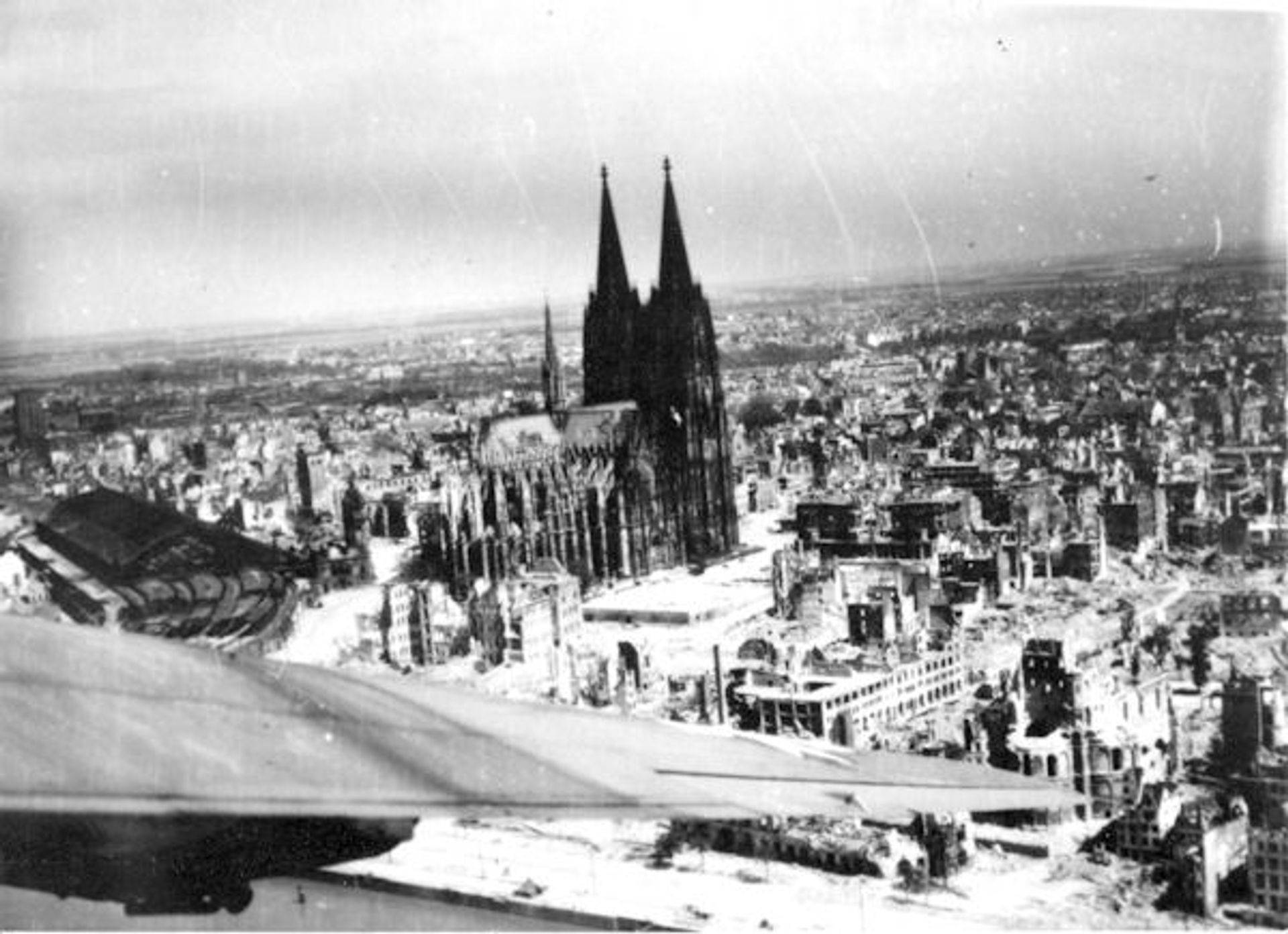

We delivered our liaison officer to the local honcho of Signal Corps. This person was a captain, a gutsy little guy, who ran around the battle lines in his jeep, moving his signal beacons. We had a particular love for the men of Signal Corps, for we knew that they had been the first home of Army fliers. Our captain invited us on a trip the next morning. He had, he said, to go into Cologne, and we were invited to go along. Speer and I piled into the back of the captain’s jeep, and he drove expertly into the very middle of the city. I was astounded at the damage our bombing had done to Cologne – there was no building in the place intact. I doubted that any plumbing worked, or any utilities at all. Particularly impressive were the gigantic craters where the RAF had dropped their five-ton “block-buster” bombs in their night saturation raids.

Our captain drove his jeep into the central square of Cologne. There was the great cathedral of Cologne, known around the world from its postcard pictures. Built to the 1300-vintage plans of architect Gerard, a designer of Amiens Cathedral, this great building had not been finished until 1880. The nave and choir vaults of Cologne are the highest of any Gothic church in the world, exceeding in altitude by one foot those of the half-cathedral of Beauvais.

I decided that I had to look inside the cathedral, but the vast church is on the river-bank and the Germans were on the other side of the Rhine. I crouched and scooted across the square, trying to look totally inconspicuous, and went into the cathedral. With devastation all around, the damage was remarkably slight. There were a few holes in the vaults and all the glass was shattered, but the main fabric was essentially intact. I was filled with admiration for medieval building methods.

When I got back to the Signal Corps jeep there was a lieutenant-colonel of infantry standing there.

“Will you fly boys kindly pack up and get the hell out of here,” he said, “The damn Germans are right across the river there with their artillery, and I don’t want any more fire drawn over here than we have to get. So please go!”

I was embarrassed. We got in the jeep to drive off, but our little captain of Signal Corps was not intimidated.

“We’re fightin’ this war too, you know, buddy,” he said, “I’ll drive where I damn well please, or where I’m ordered to!” He put the jeep in gear and took off, leaving the lieutenant-colonel standing in a cloud of dust.

Next morning Speer and I decided that we better get back to Horsham and keep running the store. We went out to our cow pasture with our returning liaison officer, climbed on board, fired up the Norseman, let the brakes off, and shoved the throttle to the firewall – nothing! The wheels were totally mired in local German mud.

We got out to discuss the problem with the little captain.

“Hell, that’s no problem,” he said. He ordered four G.l.s to help us. Two got hold of the wing struts on each side and pushed while we revved the engine. The Norseman pulled out of the mud reluctantly and taxied with two men pushing on each side. We got it rolled into take-off position.

Speer pushed the throttle full open, the G.l.s shoved like mad, and we began to roll slowly. When the G.l.s got up to their full running speed they gave a mighty shove and ran clear. We gathered speed slowly and ponderously as the tyres sloshed through more mud. The ditch at the end of the cow pasture was coming up rapidly – I figured we would leave the wheels in it, but Maurice Speer gave a mighty heave backward on the stick as we got to the ditch. We jumped it and continued rolling through the next cow pasture full of mud. There was a ditch at the end of that cow pasture. We had enough speed to jump that one more easily.

I looked ahead. Instead of a ditch there was a big hedge at the end of the third cow pasture. About halfway through the pasture Speer hauled back on the wheel. The Norseman staggered into the air in a semi-stall, dipped a bit gaining airspeed, and cleared the hedge by about a quarter of an inch. We were on our way back to England.

We had a strong headwind going across France. Speer worried that we would not have enough gas to get to Lille. So did I, but we made it without mishap. We refuelled, took off, crossed the Channel, and headed north. Our returning liaison officer was a pilot of the 392nd Bomb Group, so we delivered him to the airbase at Wendling and headed east for Horsham.

Bishop Losinga built his Cathedral in Norwich in 1096, thirty years after the Norman conquest. The people of the middle ages built gigantic churches in the centre of their cities. Today we build tall bank buildings. ‘Render unto Caesar . . .’

Norwich Cathedral once had a wooden spire which blew down in a big storm, taking a part of the original wooden roof with it, so in the 1300s the cathedral was topped with stone lierne vaulting. In 1490 a stone spire, rising three hundred and fifteen feet into the sky, was built on the old Norman foundations. This spire was our constant navigational landmark in coming home to Horsham St Faith. We could see it for miles in any direction, and as we skimmed the treetops with the little Norseman, the cathedral spire of Norwich was an especially welcome sight – it told us we were safely home again. We swung around it, lined up on our runway, put down the Norseman and taxied into the hangar.

We were back in England again after a brief adventure in the enemy’s land.

This story is an excerpt from The Day We Bombed Switzerland – By Jackson Granholm – 458th Group Navigator