458th Bombardment Group (H)

Memories of Stalag 17

This student pilot is really good! Just coming out of a string of 10 or 12 wing-over rolls, now he completes five quick loops, throttles back to a climbing stall…a quick recovery and now into a series of outside loops. Wow! The light trainer-plane is above the German pilot training base some 5 miles south of our camp. About 30 or 40 of us, all prisoners of war in the infamous Stalag 17 near Krems, Austria, are out ‘walking the compound’ on a bright late-summer morning in 1944.

Since most of us are in our late teens or early 20’s, and not always having really good judgment, we also begin shouting, “Blow up, you SOB!” and, “Crash! Crash! Crash!”…ignoring the guards in the towers sneering at our youthful exuberance. And regardless of all that, most of us DO admire the cadet’s considerable ability. We knew about that being a pilot training base because of earlier incidents. Several times one of them had ‘buzzed’ our compound, dipping well below fence level. And some of the prisoners had stacked up a few little piles of rocks. Next time one swooped down, they threw rocks in the air hoping to damage a plane.

They came very close to doing just that. So our German camp commander had called the officer in charge of the training base and told him to put a stop to the buzz jobs. Of course our American camp leader had been told all this while being ordered to tell the prisoners to knock off any more ‘flak attacks’ in the form of rocks and boulders! But my first thought when we noticed what the young student pilot was doing was that he needed a lot more altitude to be performing those aerial maneuvers. Instead of 1200 to 1500 feet, he should have at least been up at three or four thousand feet.

Whether it is the power of our concerted thought waves for the young pilot to crash…as we would like to think…or a lapse in judgment, suddenly the little trainer plane goes into a flat spin. It quickly disappears from view over the horizon. We hear a muffled boom from the explosion. The black smoke begins rolling skyward. For some reason, my first thought was, “There is another family that will be looking at an old photo of their brother or cousin 50 years from now, scanning a yellowed news clipping and remembering yet another victim of our war.” But this is now – that young pilot is our enemy. I join the other prisoners in cheering and shouting in jubilation. Also join them in a dash for our barracks when the tower guards angrily shout curses in our direction!

A few weeks after that incident, a group of us are at our regular morning recreation…walking the compound, and occasionally looking through the barbed wire prison fence at that oldish woman working in the field with her yoke of oxen., frequently thinking, “What a rough old girl!” If the oxen didn’t respond to her shouted commands just right, she would almost knock one to its knees with a fist to the head. She could easily pick up a huge sack of grain and stride across the field with it balanced on her shoulder. She looked to be about 55, a work-worn farm wife, no doubt.

A number of the men in our barracks spoke fairly fluent German. After all, many of us had grown up in German farm communities in mid-America. Two men from our barracks spoke nearly every European language and dialect. They often tuned in ‘verboten’ crystal set radios in the middle of the night. They’re listening to the BBC (British Broadcasting Company) propaganda news broadcasts…and taking notes in the dark, helped provide material for our daily newscasts. There were several of those radios in nearly every barracks, all gleaning bits of information to be turned into the camp office. All those fragmentary bits of information were put together in the camp office when no German guards were around. Each compound had their own newsman for their eight barracks. If caught, it was two weeks solitary confinement for the one reading the news.

POW radio from one of the German camps

(Photo)

Our compound news announcer had learned at one of the many New York City radio stations. He was very good, used a straightforward, clear, rapid delivery. But it was nice to be visiting my friend Maynard Standley down in the old compound every once in awhile when their news announcer arrived. He had been a dramatic actor in civilian life. To him, he was ‘on stage’ at every reading! Complete with rich stentorian tones, dramatic pauses and full-blown gestures!

Anyway, one of our skilled linguists was out in the compound that morning and struck up a shouted conversation with that burly woman. Turned out she was not a German farmer’s frau. She was Polish, and as she said, “A slave laborer.” She was not in her mid-fifties or older as she appeared, as she shouted back across those fences, “I’m 32 years old. Working 14 or 15 hours a day, 7 days a week will do this to anyone.” Once again we realized that, even weighing less than 100 pounds, stomachs chewing on our backbones day and night…it could still be a lot worse! And probably would be before the war ended.

And to be reminded just how much worse, we had only to look across the fences separating our part of the camp from the half filled with Russian prisoners. There were never any Red Cross parcels for them. Their ration of ‘ersatz’ bread was even slimmer than ours. Their dippers of soup made from leaves and stems of rutabagas, and liberally laced with maggots as ours was, were even less than what we received. Add to that the knowledge that their government really didn’t much care what became of those prisoners. Coming from poor peasant families there was little for them to look forward to when…and if the war ended.

Back when we were in Stateside training it seemed we were all too frequently lined up to receive immunization shots…usually six injections, yet another smallpox vaccination, a blood-type test and a Tyne test for tuberculosis. Since we were aircrew members, most of us had received those shots a dozen or more times before and after going overseas. The Army Air Corps believed in being thorough! Turned out, the Russian government either didn’t have enough organization to immunize their soldiers…or just didn’t think it necessary. After all, mass quantities of people were one thing they had a lot of!

Russian prisoners who died were carried past our compound on canvas litters down to the burial ground in the woods at the far corner of the camp. Of course, those of us in the compound would always stand at attention as the litters were carried by. The most we ever counted was 36 in one day. According to camp officials, most were dying of typhus. And it probably spread more quickly since the other Russian prisoners didn’t tell the German guards one was dead for several days, or until the stench became unbearable. The daily ration for each barracks was based on body count. Nobody said the body had to be alive!

Our barracks chief was T/Sgt Bayne P. Scurlock [gunner, 91BG, shot down first Schweinfurt, August 17, 1943]. He was ‘one of the old guys’. Must have been 27 or 28. He made a little speech about something or other nearly every afternoon, keeping us informed on events in the camp and often worked in a little fatherly advice on how to survive as a prisoner. His comments on many of those Russian prisoners dying were to encourage paying respect as the bodies were carried by. “It helps show the Germans that all of us Allied Forces prisoners stand together.” And, “Aren’t you glad now that we had those immunizations? That could be some of us on those litters!”

Late that summer of 1944, probably September, we were ordered to prepare for an inspection by a very high-ranking German officer. And they even issued each barracks a couple of those old-time, medieval brooms made from tied-together twigs from some sort of bush.

Anyone who has ever looked at pictures of pioneer homes might remember seeing one standing in a corner. To our surprise, those brooms worked quite well. When the day came for the Field Marshal and his entourage to do their inspecting, we had our barracks in order as well as possible considering how crude they were.

The official party noticed one of our hand-drawn battle maps of the Eastern Front glued on the chimney in the middle of the barracks. One of our German officers, Luftwaffe Major Eigl started to apologize since battle maps were not supposed to be displayed, although common in most barracks. However, the Field Marshal just laughed and remarked how well drawn it was…but could be a bit more accurate. He then proceeded to carefully move some of the pins and push the Russian advance back about 20 kilometers from where we had it.

Russian advances on the Eastern Front June 1944 – January 1945

All the inspection party had a big laugh, and moved on to the next barracks. Interestingly enough, the next day when our news-reader came around, one of the items was that the Russian advance had been mistakenly listed far in advance of where it actually was! An even more telling exchange took place just before the party left our barracks. The Field Marshal had noticed how very young most of the American prisoners were. “These men aren’t soldiers…they are just boys!” Major Eigl said, “Yes Field Marshal, they may be just boys, but they have certainly managed to destroy our factories and most of our cities.” He nodded and agreed that was true.

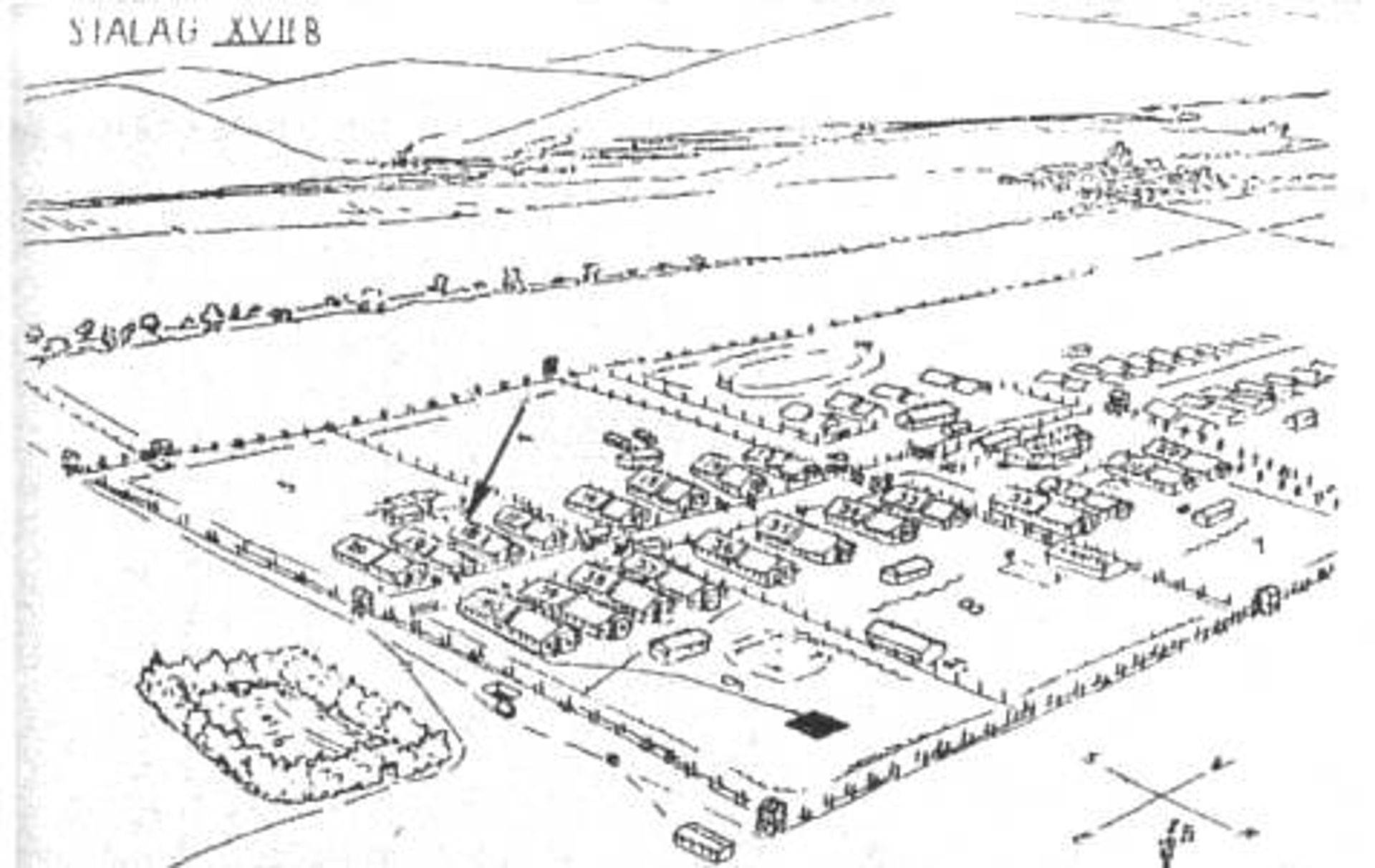

Our barracks was number 30, near the Russian half of the camp at far right. The small woods at the far left was the burial ground for all prisoners. The burial litters were carried down the path, down the north side of the camp.

Cedric Cole, courtesy his daughter Sue Knepper